Summary

- After Stalin

- Moscow Conceptualism

- The Collective Action

- Glasnost policy – new turn in Russian cultural life

- The wild 1990s

- Putin’s term: revival of actionism in the 2010s

After Stalin

The Khrushchev Thaw came after the death of Stalin and lasted about 10 years. The domestic policy of the Soviet Union in these years was characterized by the debunking of the personality cult, the release of political prisoners, and the lifting of censorship. In the arts, there were significant changes as well. Repressed artists returned from gulags, banned magazines and books became more accessible, collections of Western art returned to museums, and avant-garde art could be seen at apartment exhibitions.

But the relative liberalization of art ended as abruptly as it had begun. In 1962, Khrushchev lashed out at contemporary artists at an avant-garde exhibition. From that day on, public exhibitions were banned, but artists continued to exhibit in private apartments and sell work to foreign diplomats. This is how the Soviet Nonconformist Art of the 1960s came into being.

The most popular association of nonconformist art was the Lianozovo School. The artists, led by Oskar Rabin, worked in a small flat in a village near Moscow. Rabin painted what he saw around him: “I lived in barracks, many Soviet citizens also lived in barracks. Now I have moved to a block house and am painting blocks of block houses that surround me”. There was a social protest in Rabin’s work, despite its distorted but generally realistic reflection of reality. One could see such naivety as a social and political instrument that helped the artists to cope with the historical traumas.

The turning point of this time was the Bulldozer Exhibition of 1974. The police disrupted the Lianozovo School demonstration, and the artists’ works were bulldozed right on the spot. Foreign media reacted to the event: “The young men who appeared to be organized into teams, ripped up, trampled, and threw more than a dozen paintings into a dump truck to be covered with mud and driven away. Artists who protested were roughed up and at least five were arrested”. The Soviet Nonconformist Art became known around the world. The authorities had to make concessions. They allowed the artists to exhibit their work and canceled their criminal status of social parasitism.

Russian Actionism: The artists on the Bulldozer Exhibition, 1974, Moscow, Russia. From the book Bulldozer Exhibition by Viktor Agamov-Tupitsyn.

Sots Art is another interesting movement of that time. Its members also took part in the Bulldozer Exhibition. If western Pop Art was a postmodernist game to deconstruct popular culture, then Sots Art aimed to deconstruct ideologized art. The Soviet Sots Art group Komar and Melamid appealed to kitsch images: “We deconstructed socialist realism as an ideology and discovered it as art”. By combining different styles in their works, the artists anticipated postmodernist techniques in art. After emigrating to the United States, the group made a name for the action First duty-free trade between the U.S. and the USSR: We Buy and Sell Souls. The artists set up a trading corporation to sell and buy souls (quite like NFT). The action was particularly popular. They did several hundred deals and even acquired the soul of Andy Warhol.

Moscow Conceptualism

The school of Moscow Conceptualism was crucial for the development of Russian Actionism in the 1970s. Artist Yuri Albert defines this concept in his memoirs as follows: “Conceptualism is an art whose main task is not to create works of art, but to find out experimentally what a work of art is, what art is, to build models of art. It is the art that is analytical, non-aesthetic, and unimaginative”.

Moscow Conceptualists, as structuralists, were fascinated by the text and saw the world as a textual message. Yet, there was a significant difference between Western and Moscow artists. The former worked with the subject as an object, while the latter included the subject in the surrounding context. Boris Groys explained this difference by the Western individualistic and Russian collective consciousness. Ilya Kabakov, the main artist of Moscow Conceptualism, believed that behind the visual “there is a narrative that exists and works at all levels, both in creating these works and in understanding them”.

Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov implemented the ideas of conceptualism in a new genre. The albums consisted of paper sheets with images and texts explaining them. Kabakov’s Sitting-in-the-Closet Primakov is a story of a man trapped in a wardrobe. Each sheet shows a black rectangle with a commentary in the lower right corner. We see what the character sees sitting in a pitch-black room – nothing. The actions that take place around him are captured by the artist in the form of a short commentary.

In this context, it is difficult not to mention Malevich. What is the difference between the Suprematist Black Square and the conceptualist rectangle? The avant-garde artists of the early 20th century aspired to achieve the Absolute. Malevich and Kandinsky in their theoretical works developed the idea of detachment from the outside world and striving into the inner one. The authors’ aspiration towards the Absolute in art derives from the concept of Sublime in Burkean and Kantian philosophies, continues Schlegel’s romantic paradigm, and relies on the theories of Western artists, notably Gleizes and Metzinger. Interpreting Kabakov’s Sitting-in-the-Closet Primakov is much easier – the artist gives the instructions for constructing art.

The Collective Action group specialized in actions that revealed the conventionality of the world around. The action Out of Town consisted of a dozen volumes, each backed by a preface and descriptions of acts. Andrei Monastyrski, a member of the group, described these activities as a “journey towards Nothingness” to explore the reactions of participants and spectators to what was happening.

In Slogan 1977, artists went to a forest, away from human eyes, and stretched a canvas between trees with the message: “I’m not complaining about anything and I like everything, even though I’ve never been here and know nothing about these places”. The text in white letters on a red background brought associations of the Soviet propaganda posters. But it had no meaning and no ideological function. The artists deconstructed a familiar cultural item and demonstrated the significance of the context.

Russian Actionism: Collective Action, Slogan, 1977, Moscow region, Russia. Photo by Andrei Monastyrsky.

Time for Glasnost

A new turn in Russian cultural life began with the Glasnost policy adopted at the 1986 Congress of the Communist Party. This policy put an end to restrictions on social and commercial activity and legalized the underground. In 1988, Sotheby’s held its first auction in Moscow. Collectors bought the underground for as much as the avant-garde. In St. Petersburg, the art market began to develop freely. New galleries of contemporary art opened one after another, holding exhibitions, auctions, and biennales.

The wave of liberalization of artistic activities in the 1990s created many independent collectives. The most influential of these were the Mitki and the New Artists. The members of the Mitki followed a particular style of behavior – purposely simple and rustic. Researchers often consider their art through the anarchist paradigm. The artists did not abstract away from the world around them but adhered to the idea that there is no opposing reality.

The aesthetics of the New Artists were found in Sergei Solovyov’s 1987 film Assa and in the music of Leningrad rock bands such as Kino. Their first action was a hole in the wall with the inscription Zero Object. At the exhibition, this object was the implementation of the idea of the immateriality of material, playing with authority in the Dadaist tradition.

Political actions and conceptualist performances have been held throughout the development of Russian underground art. After Glasnost, it wasn’t forbidden to create independent art anymore, so the artists went further and became political activists.

Movie still from Assa, 1987, directed by Sergei Solovyov.

The Wild 1990s

Moscow Actionism stands out in the cultural scene of the country in the mid-to-late 1990s. The group participated in the political life of the country through scandalous performances. It gave rise to the escalation in art, which manifested itself in a deliberate exacerbation of the audience’s reaction to the actions. The actionists used “violence on the will and moral value system of the audience”. It soon escalated into a radicalization of visual expression in other areas as well.

In 1991, participants in the E.T.I. group body-painted obscene words on the pavement of Red Square. Action TEXT coincided with the passing of the law “On Morality”, which banned swearing in public places. They charged the participants of the protest with criminal mischief. The case was closed a few months later.

In 1993 action Necesiudik’s Journey to Brombdingnag Land, Anatoly Osmolovsky climbed onto the shoulder of the Vladimir Mayakovsky monument in the center of Moscow. He condemned the Yeltsin regime for the betrayal of Soviet avant-garde ideas. After the Bolshevik revolution, Mayakovsky supported the government with poems. They installed the monument to Mayakovsky almost 30 years after his death in 1930. It was a betrayal that erased the work of the futurist, who “hated any kind of deadness”. The symbol of progress was frozen in the form of a stone monument.

Russian Actionism: Anatoly Osmalovsky, Necesiudik’s Journey to Brombdingnag Land, 1993, Moscow, Russia. Archive of Osmolovsky.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Yeltsin tried to carry out economic and political reforms in Russia. The pro-communist parliament opposed him, and in 1993, Yeltsin tried to dissolve it. In response, the parliament voted to remove him from power. Yeltsin engaged the army, and tanks shelled a parliament building called the White House, causing it to burn down. The action Shame on 7 October took place against the backdrop of the burnt White House. The black T-shirts on the artists represented the upper level of the White House, naked feet symbolized the lower level, and naked genitals signified the attitude to what had happened.

A lack of confidence in parliamentary democracy caused new political actions throughout the decade. In 1998, artists from the Extra-Governmental Control Commission built a barricade of cardboard boxes in Moscow and chanted the slogans from the student protests in France thirty years earlier. The list of unrealistic demands included monthly payments, the legalization of drugs, and the possibility to travel around the world for free.

Another trend was a profanation of the sacred. Oleg Kulik has repeatedly turned to religious motifs. In The New Sermon, the artist, wearing a chiton and a crown of thorns, mooed standing on a meat chopping deck with a pork carcass in his hands. As part of the action The Piglet Makes Gifts, he butchered a pig and handed out the meat to the audience. In this way, the author spoke about the imperfection of the universe and consumerism.

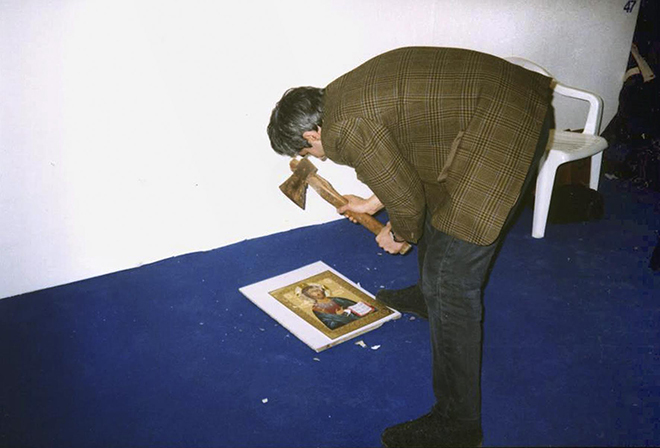

In Experiences of Iconoclasm, Avdei Ter-Oganyan presented a series of reproductions of deformed Orthodox icons. The action implied the idea of the fake nature of replicated sacred images. Art historian Andrei Erofeev wrote that the aim of the action was to “expose the shamelessly commercial and political exploitation of the classical Orthodox icon in contemporary Russian society”.

In 1998, the artist organized the scandalous Young Godless campaign. He chopped up reproductions of icons in the exhibition hall with an ax. The action resulted in a trial for inciting ethnic and religious hatred.

As part of the performance Don’t Believe Your Eyes in 2000, Oleg Mavromati was nailed to a cross in front of the Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow. The crucifixion took place after the Ter-Oganyan case. It addressed the authorities as an adversary of radical actionism. He explained his actions as “suffering, a real sacrifice on which art has long been speculated”. Mavromati was prosecuted under the same article.

Russian Actionism: Avdey Ter-Oganyan, Young Godless, 1998, Moscow, Russia. Archive of the OVCHARENKO Gallery.

Putin’s Third Term

Putin’s decision to run for the presidency for the third time and unprecedented falsifications in the parliament election in 2011 killed any hopes left for the democratic future of Russia. It led to actionism being once again on the rise in the 2010s.

In the 2010s, activism began with the performances of the group War, which included Pussy Riot. Two actions were set against police brutality and in honor of political prisoners. In the Palace Coup action, the group overturned several cars with police officers inside. The Mento-Auto-Da-Fé performance involved setting fire to a police prisoner transport vehicle. As a protest against the heightened security measures, War held an action in which the artists painted a phallus on the Liteyny Bridge in Saint Petersburg. It turned out to be in front of the windows of the FSB, the Russian security service, after the bridge had been lifted.

The Pussy Riot participants held a punk moleben (supplicatory prayer) called Virgin Mary Put Putin Away in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior. The song criticized the ties between the leadership of the Moscow Patriarchate with the security services and Putin: “Patriarch Gundyay believes in Putin. He’d better believe in God, bitch”. The publication of the video led to a criminal investigation. The Pussy Riot campaign was considered extremist.

Russian Actionism: Pussy Riot members sitting in a glass-walled cage during court hearing in Moscow, 2012. CNN.

Petr Pavlensky’s Stitch action reflected the verdict of the Pussy Riot case. The artist sewed up his mouth in front of the Saint Isaac’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. He continued to work in the body horror genre and in 2013 came out with the action Carcass. Pavlensky wrapped himself naked in barbed wire in front of the Legislative Assembly building. In his most sensational action Fixation, he nailed his scrotum to the paving stones of the Red Square. Pavlensky’s work reflects the problem of political indifference in Russian society: “The reason for my actions is the authorities’ desire to frighten people by imposing fear as an instrument of governance… The authorities seek to objectify the individual, to turn him into a predictable function”.

In his last high-profile action in Russia, Pavlensky set a door of the FSB building in Moscow on fire. He explained it as a gesture against terror and round-the-clock surveillance of the people led by the agency. The court imposed a half-million rubles fine for “damage to an object of cultural heritage”, which was the FSB building. Later, Pavlensky emigrated to France without paying off the fine.

In this way, political art activism emerges at times when autocracy flourishes. Artistic practices in such times deviate from the aesthetic course towards the politicization of art. As for Russian actionism, it has come a long way from the death of Stalin to Putin’s third term, from the destruction of paintings at a bulldozer exhibition to criminal cases for dancing in a church.

Russian Actionism: Petr Pavlensky, Threat, 2015, Moscow, Russia. Photo by Nigina Beroeva / Agence France-Presse, via Getty Images.