Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

Today’s modern construction techniques allow us to build huge structures in just a few months or years. For example, the Shard in London was built between 2009 and 2012. That was not the case throughout human history, the Egyptian pyramids and medieval cathedrals took generations to complete. Sagrada Familia in Barcelona is a church that reminds us of how it was done in the olden days. Its construction started 140 years ago and, while it is stunning, it is still not completed. Join us to explore its rich history and amazing architecture.

Sagrada Familia overlooking Barcelona, Spain. Catalan News.

We are used to the abbreviated name of the church, Sagrada Familia, but the full name is Basílica i Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família. The idea for constructing the church came from a bookseller, Josep Maria Bocabella. He was a devout Catholic and the founder of the Spiritual Association of Devotees of Saint Joseph. It was meant to be an expiatory temple, a place made to commemorate the reparation of sins made against God or the laws of the Church. The construction is funded solely from private donations. This uncertain source of funding certainly contributed to the extended timeline.

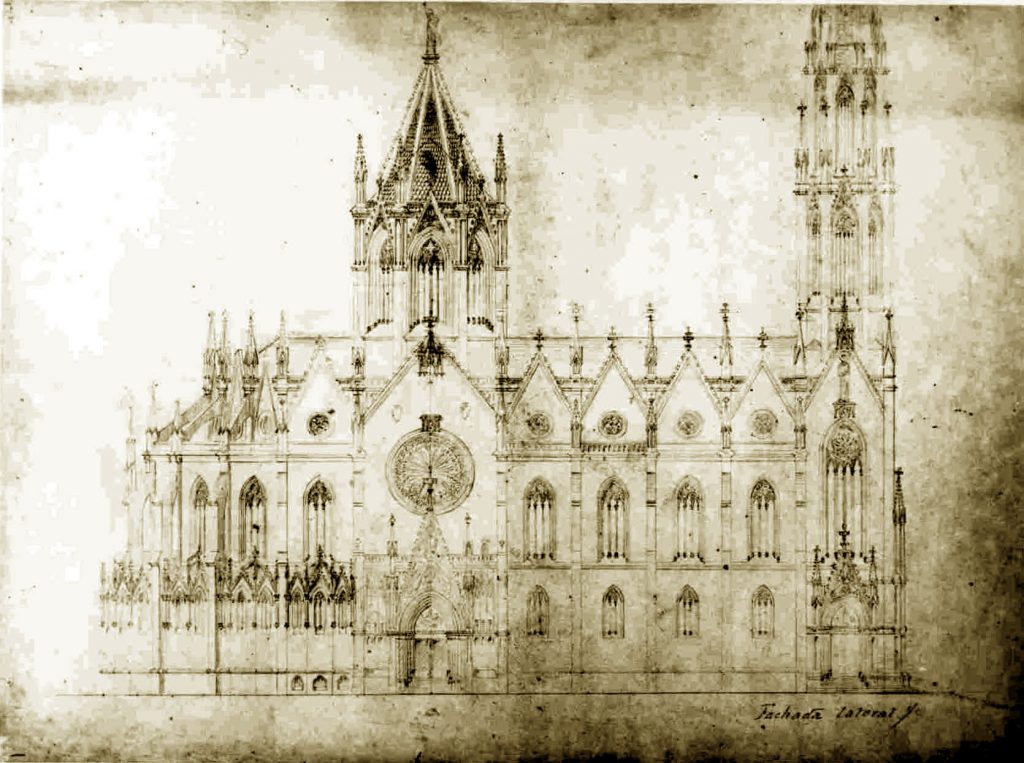

Francisco de Paula del Villar, the original design of Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain. Sagrada Familia website.

The first architect was Francisco de Paula del Villar, who created a quite conservative neo-Gothic design in 1882. However, due to disagreements regarding the cost of construction, Villar resigned and Antoni Gaudí took his place in 1883. Gaudí was very religious, and the church was to become his opus magnum. He spent the remainder of his life working on it.

Initially, he combined this with his other commissions, but from 1914 on he devoted his time solely to the church. He even lived on the construction site at some point and created a school for the worker’s children. By the time he died in 1926 only a quarter of it was completed. Only 10 years later, during the Spanish Civil War, the church was vandalized and set on fire. Sadly Gaudí’s designs and architectural models were either damaged or destroyed.

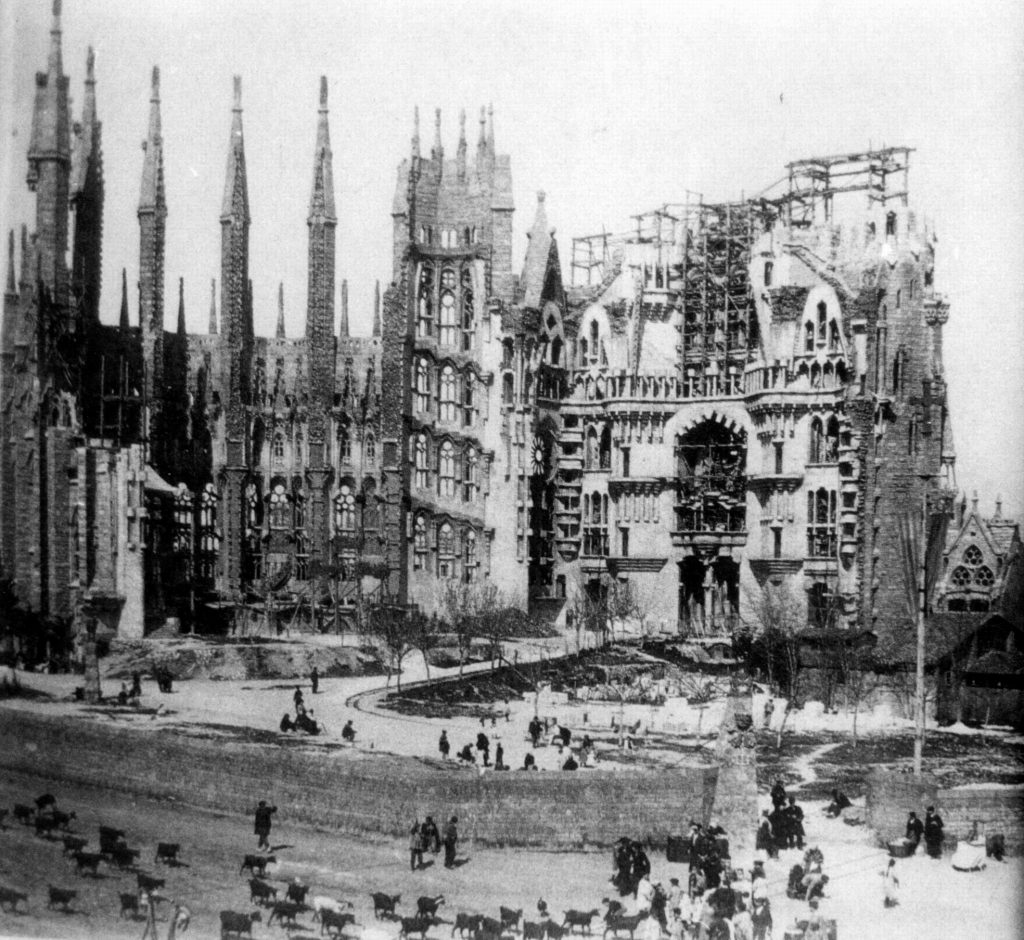

Sagrada Familia in construction, 1915, Barcelona, Spain. Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Recreating the models and designs took 16 years. In the 1950s construction restarted but at a slow and unstable pace. The introduction of computer-aided design methods gradually helped to speed up the process. In addition, opening up the basilica to tourists helped ensure a more stable stream of funding. By 2010 construction passed the halfway point and the church has since been consecrated as a minor basilica. The plan was to complete it in 2026, to mark the centenary of Gaudí’s death. Due to the COVID pandemic, this deadline is now in jeopardy.

Sagrada Familia in construction, 1930, Barcelona, Spain. Photo by Walter Mittelholzer/ETH-Bibliothek.

Gaudí took the design in a different direction from the original neo-Gothic style proposed by Francisco de Paula del Villar. It is a mix of Catalan Modernism, Spanish Late Gothic, and Art Nouveau. It is a church like no other, as it has also been shaped by its long construction. While every effort is made to reconstruct Gaudí’s original intention, a lot of it is just an educated guess. It is quite easy to recognize which parts were built earlier and later as new construction technology leaves its mark as well. The building seems to grow organically, and I think this is something that aligns with Gaudí’s ideals in its spirit.

Sagrada Familia within the street network of Barcelona, Spain. Sagrada Familia website.

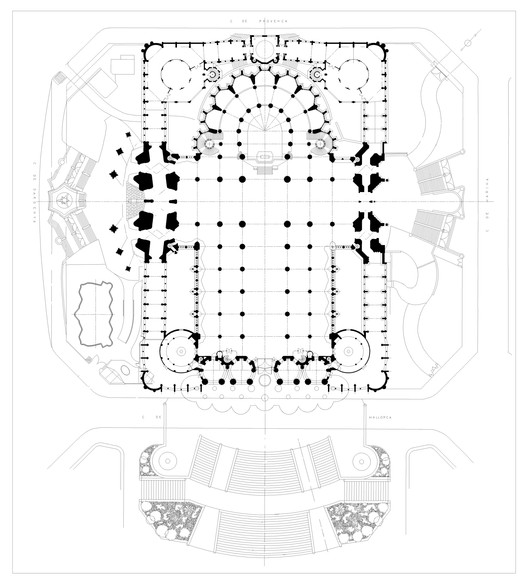

The plan for the basilica is probably its most traditional part. Its ground plan has obvious links to earlier Spanish cathedrals such as Burgos Cathedral, León Cathedral, and Seville Cathedral. However, unlike many of these churches, Sagrada Familia was not built on an east-west axis. Instead, it follows a diagonal orientation in line with much of Barcelona’s planning. It places the church on a southeast-northwest axis.

The plan is by no means simple as it includes double aisles, an ambulatory with a chevet of seven apsidal chapels, a multitude of steeples, and three portals. It also has an unusual feature: a covered passage or cloister which forms a rectangle enclosing the church and passing through the narthex of each of its three portals.

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, ground plan, Barcelona, Spain. Archdaily.

We know that Gaudí originally designed the church with a total of 18 spires. They represent in ascending order of height the Twelve Apostles, the Virgin Mary, the four Evangelists and, tallest of all, Jesus Christ. Gaudí planned that even the tallest spire would not be higher than the Montjuïc hill, as no human creation should surpass that of God.

Antoni Gaudí, Passion façade of Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain. LiveLifeBCN.

The Church will have three grand façades: the Nativity façade to the East, the Passion façade to the West, and the Glory façade to the South (yet to be completed). The Nativity façade was built before work was interrupted in 1935 and bears the most direct Gaudí influence.

The Passion façade was built according to the design that Gaudi created in 1917. It is especially striking for its spare, gaunt, tormented characters, including emaciated figures of Christ being scourged at the pillar and Christ on the Cross. These controversial designs are the work of Josep Maria Subirachs.

The Glory façade, which began construction in 2002, will be the largest and most monumental of the three and will represent one’s ascension to God.

Antoni Gaudí, Nativity façade of Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain. Covenant – The Living Church.

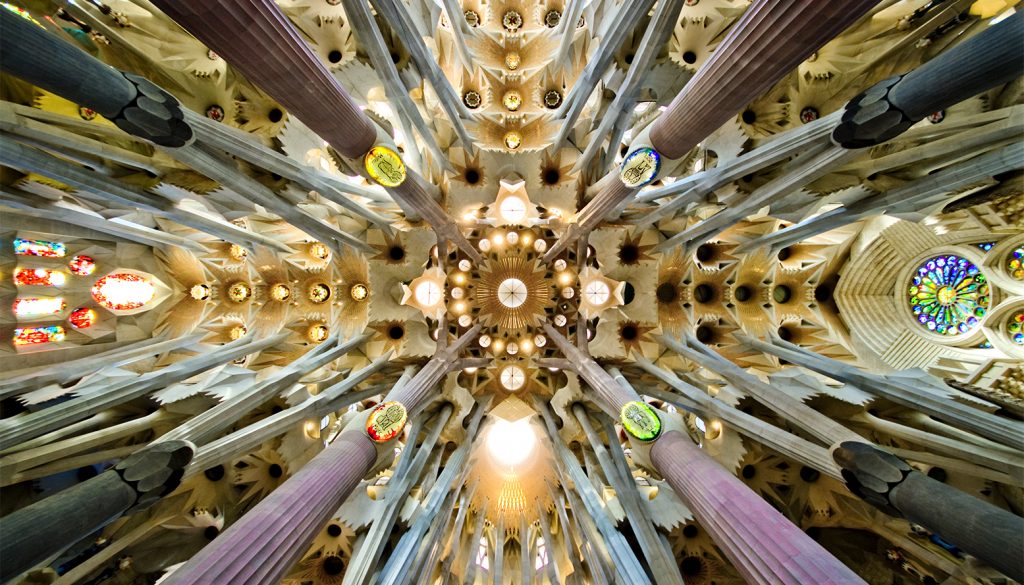

The interior of Sagrada Familia is even more stunning than its exterior. Gaudí thought of everything, including acoustic studies to ensure the tubular bells he planned for the spires would produce the desired effect. The church plan is that of a Latin cross with five aisles. The columns branch out at the top to better carry the load, but also give an organic tree-like effect. Gaudí also plays with their shape, as it changes with the height of the column.

Essentially no interior surface is flat; the ornamentation is comprehensive and rich, consisting in large part of abstract shapes which combine smooth curves and jagged points. Even detail-level work such as the iron railings for balconies and stairways is full of curvaceous elaboration. All this detail and skillful use of light create an illusion of being within a huge organic structure, rather than one constructed from stone.

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, interior, Barcelona, Spain. Sagrada Familia website.

Antoni Gaudí stands very much on his own as an architect. While typically associated with Art Nouveau, he took this style beyond surface decoration and let the organic, flowing lines guide his entire design, including construction.

Antoni Gaudí, Nativity façade of Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain. Blog Sagrada Familia.

While Gaudí’s design parts way with the neo-Gothic, it keeps the spirit of striving upwards, toward God. In his youth, Gaudí was influenced by John Ruskin‘s analysis of the Gothic, with the praise of its expressive, even grotesque qualities. In this design, Gaudí prioritized the final effect over sticking strictly to one style. Here the form serves the function, and function was defined by the spiritual need.

All parts come together to praise God, celebrate Jesus and his sacrifice, and strike fear into sinners. One of the clearest examples is the façades: the Nativity one softer and joyful, the Passion harsh, striking and evoking fear, and the Glory (still under construction) dazzling us with the power of God.

Antoni Gaudí, Passion façade of Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain. Twitter.

Gaudí first thought of the impression he wanted to achieve and only then looked for inspiration on how to evoke it. He didn’t hesitate to draw from Gothic, Art Nouveau, the organic world, or Modernism as long as it served the purpose he had in mind. He refused to become hostage to a specific style and make compromises in order to comply with it. Instead, he went above and beyond, looking for means to pass on his message.

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, detail of the nave, Barcelona, Spain. Photo by SBA73 via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

While Sagrada Familia is a testament to his genius, Gaudí was very aware that the work would be much larger than him. He humbly accepted that he would be one of its many architects.

There is no reason to regret that I cannot finish the church. I will grow old but others will come after me. What must always be conserved is the spirit of the work, but its life has to depend on the generations it is handed down to and with whom it lives and is incarnated.

Antoni, Gaudí, Nativity façade of Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain. Photo by C messier via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

In a bit more humorous vein is also observed that his “client is not in a hurry.” As we track the progress of the construction and may be the first generations to see it completed, do you think it was worth the wait?

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!