10 Iconic Floral Still Lifes You Need to Know

Flowers have long been a central theme in still-life painting. Each flower carries its own symbolism. For example, they can represent innocence,...

Errika Gerakiti 6 February 2025

Christianity has a saint for everything, literally everything. So let’s talk about Saint Luke. Not only is he one of the Four Evangelists and therefore one of the most important saints, but he is also the patron of artists. For this reason, many academies and guilds have been named after him. Moreover, he has served as an inspiration to numerous paintings throughout European art. Now let’s dig into his story and his representation in Western art history.

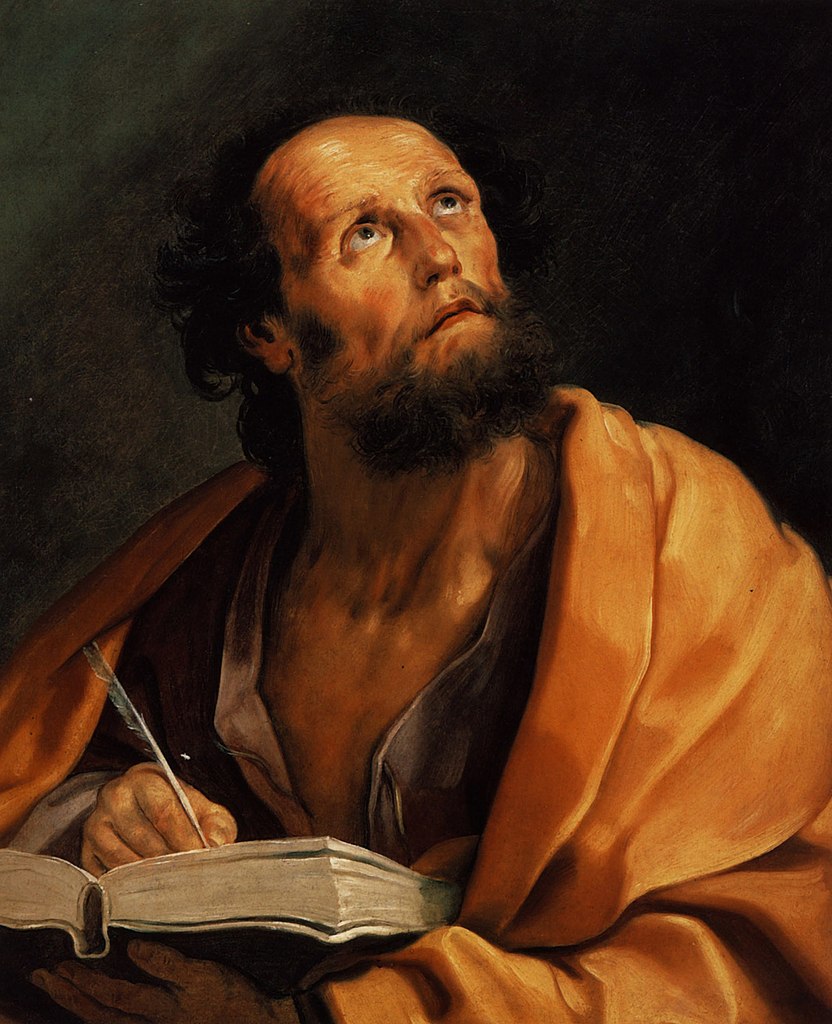

All saints begin as simple people and Saint Luke, similarly, came from a humble background. According to Jacobus de Voragine’s The Golden Legend, he was a gentile from Antioch, Syria. Actually, there is some debate whether he was an actual disciple of Christ or if he converted later. Regardless, he achieved one of the most important places in Christianity as one of the Four Evangelists. For this, he is part of the tetramorph and his representation is a winged ox. He wrote the Third Gospel as well as the Acts of the Apostles. As such, artists commonly depicted him writing or holding a book like the other Evangelists.

Guido Reni, Saint Luke, 1621, Bob Jones University, Greenville, SC, USA.

Commonly, saints are patrons to several things and Luke is no exception. In fact, he was a physician, hence him being their patron too. In Letter to the Colossians, St. Paul calls him “the beloved physician”. Actually, medicine and art are not such a rare pair. For instance, many professors at Western art academies were physicians that taught anatomy to artists. Furthermore, both professions require detailed knowledge of the human body. But this doesn’t completely explain why he is the patron of artists. To understand that, we need to talk about the Virgin Mary and the Byzantine Empire.

Icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, 15th century, British Museum, London, UK.

According to Eastern Church tradition, Saint Luke is considered the first iconographer. Though there is no evidence, writings started to appear in the 8th century referring to his icons of the Virgin and Child. His gospel stood out for its detail in the narration of Christ’s childhood. It is probable that this caused the attribution, as it showed a deeper degree of intimacy between them. However, most probably, he was either younger than Jesus or wasn’t even a contemporary. Nevertheless, Christian tradition has accepted the story for centuries.

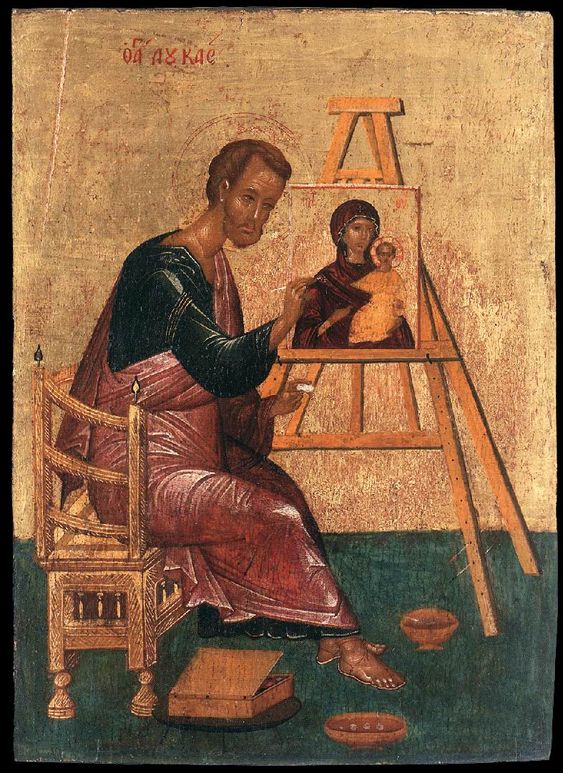

St. Luke Paints the Icon of the Mother of God Hodegetria, 14th century, Icon Museum Recklinghausen, Recklinghausen, Germany.

Of the Evangelist and Apostle Luke all his contemporaries said that with his own hands he painted both Christ the Incarnated himself and his purest Mother, and their images are preserved in Rome, so it is said, with great honor; and in Jerusalem, they are exhibited with meticulous attention.

On the veneration of Holy Icons, 8th century. Cited in The Shaping of an Icon: St Luke, the artist by Rebecca Raynor, 2015.

The myth started during the Iconoclasm era in the Byzantine empire. They speculate that iconophiles used this myth to defend the images at churches. Let’s not forget that most people in the Middle Ages were illiterate. Therefore, the Church used images as didactic instruments. If a saint was responsible for the creation of icons, then images could exist. Furthermore, a 15th century account by Gregory of Kykkos established that the Virgin herself commissioned the portraits. Apparently, the Virgin recognized Saint Luke’s talent. This only further validated the existence of icons. Not only that, but the Archangel Gabriel provided him with a wooden panel. As far as holy images go, these ones certainly earned a high place.

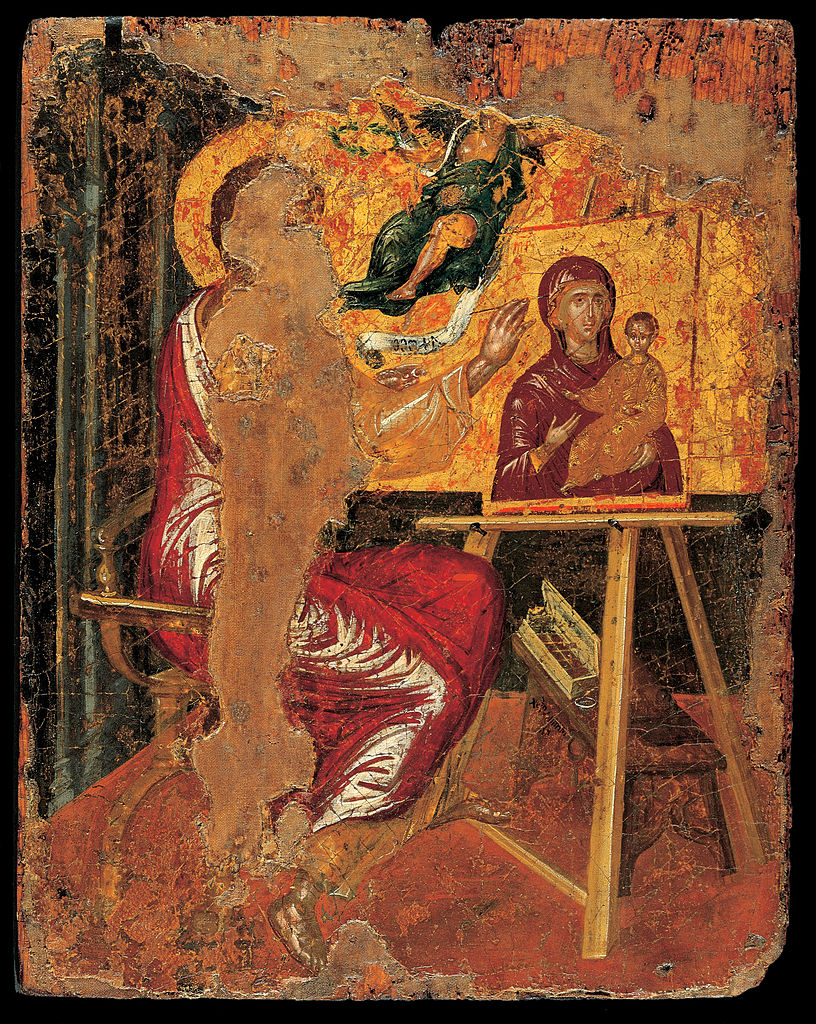

El Greco, St Luke Painting the Virgin, 1560-1567, Benaki Museum, Kolonaki, Athens, Greece.

Regardless, by the 8th century, people started to attribute certain icons to Saint Luke himself. One of the characteristics was the use of the encaustic technique (also used in the Fayum Mummy portraits). It consisted basically of adding hot wax to pigment and applying it to wood. Additionally, when determining attribution, they considered the age of the piece and its holy power to perform miracles.

Icons attributed to Saint Luke functioned similarly to important relics. Whichever church had one of his icons would increase in popularity and importance. Consequently, the number of attributions increased by the centuries to the point that it became an excess. However, there were no stopping people from believing certain portraits were the saint’s creation. It also became a source of legitimacy for different political and ecclesiastic authorities.

Berlinghiero Berlinghieri, Madonna and Child, 13th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

This icon above presents a half-length portrait of the Virgin holding Christ. She is pointing towards him as the path towards salvation. It is called Hodegetria because the original was displayed in the Monastery of the Panaghia Hodegetria in Constantinople. Regardless, there are various writings that name Saint Luke as its author. Unfortunately, during the Ottoman conquest of the city in the 15th century, it disappeared.

Yet, some original attributions did survive. One of them is the Madonna of Saint Sisto in Santa Maria del Rosario in Rome. Whether Saint Luke really painted it or not, it certainly served the church and the city to attract believers and assert its prestige.

Madonna di San Sisto, 6th century, Santa Maria del Rosario, Rome, Italy.

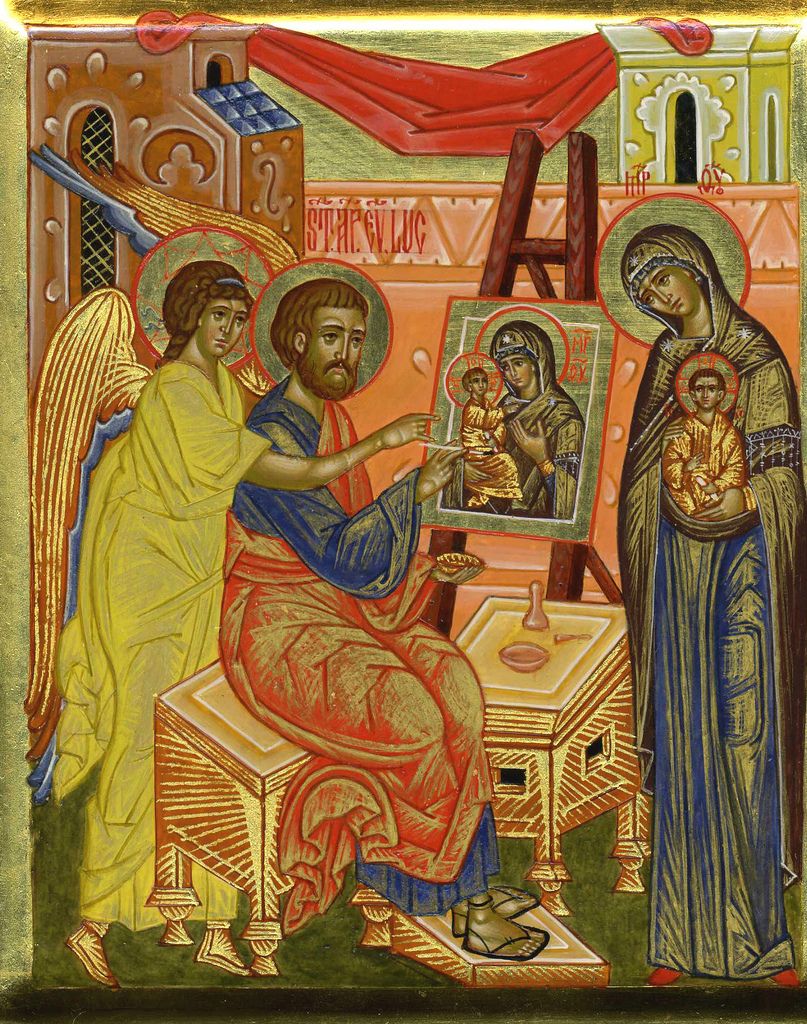

In Eastern tradition, early images of Saint Luke are scarce but enough to give us an idea of the general iconography of the Evangelist as an artist. Usually, he appears seated on the left with an easel in front of him. As the story goes, he is painting the Virgin and Child. Sometimes it is only him, and others he is with are the “Divine Wisdom.”

Luke the Evangelist painting Vladimirskaya icon of Our Lady, 16th century, Art Museum-Reserve, Pskov, Russia.

But the story of Saint Luke’s paintings didn’t stay in the East. Western tradition adopted the narrative and has been spreading it through its art since the Middle Ages too. Apparently, the story of Saint Luke in this part of the continent came from the Golden Legend. While the chapter about him does not touch upon his supposed artworks, he appears in St. Gregory the Pope’s one.

…he did do bear an image of our Lady, which, as is said, S. Luke the Evangelist made, which was a good painter, he had carved it and painted after the likeness of the glorious Virgin Mary.

The Golden Legend, 13th century.

The earliest images of Saint Luke in the West go back to the 14th century. While some elements from the Byzantine tradition persist, there are important changes through time. Here, an addition is made. As it was said before, he is part of the tetramorph. It seems the Western artists took this more into account as an ox is recurrent in their images. Moreover, the Virgin and Child posing are featured in many paintings, especially in the Northern European and Italian ones.

The legend of Saint Luke and its depiction was a common theme until the 18th century. Afterward, it sort of died out. Nonetheless, it remained in numerous places. In fact, Churches, chapels, and other religious buildings were dedicated to the saint. Furthermore, several institutions in the art world took his name. For example, the famous Accademia di San Luca in Rome and many guilds of painters in Europe. Today, we still celebrate his day on October 18.

In reality, the memory of Saint Luke never abandoned totally the scene. In the 19th century, the famous Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote the poem Saint Luke the Painter (for a drawing).

Give honor unto Luke Evangelist;

For he it was (the aged legends say)

Who first taught Art to fold her hands and pray.

Scarcely at once she dared to rend the mist

Of devious symbols : but soon having wist

How sky-breadth and field-silence and this day

Are symbols also in some deeper way,

She looked through these to God and was God’s priest.

And if, past noon, her toil began to irk,

And she sought talismans, and turned in vain

To soulless self-reflections of man’s skill,—

Yet now, in this the twilight, she might still

Kneel in the latter grass to pray again,

Ere the night cometh and she may not work.Sonnets for pictures, 1850.

R. Raynor: “The shaping of an icon: St Luke, the artist”, Byzantineand Modern Greek Studies, 2015, pp. 161-172. Accessed 17 October 2021.

R. Raynor: “In the Image of Saint Luke: The Artist in Early Byzantium,” Academia.edu, 2012. Accessed 17 October 2021.

C. Boeckl: The Legend of St. Luke The Painter: Eastern and Western Iconography, 2005. Accessed 19 October 2021.

J. de Voragine: The Golden Legend: Or, Lives of the Saints, Volume 6, Internet Archive, 1900. Accessed 16 October 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!