Summary

- Sakura is a Japanese ornamental tree and hanami is a tradition of flower viewing, which dates back to the Nara period (710-794 CE).

- For samurai, sakura symbolized the way of the warrior. It also symbolizes new beginnings and optimism.

- Cherry trees thrive in many parts of the world where the climate is suitable. The US owes its cherry blossoms to Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore.

- Artists have different ways of depicting sakura: by focusing on the hanami party itself or portraying the blossoms in all their fragility and beauty. Sometimes sakura is placed beside symbols of long-enduring power such as buildings, rivers, and even Mount Fuji.

But, First of All—What Exactly Is a Cherry Blossom Tree?

The answer may surprise you. The cherry blossom tree is not the kind of cherry that gives maraschino cherries. The sakura, its Japanese name, is mostly an ornamental tree. Cherry blossom trees flourish in regions with warm and humid summers, where winters are not too extreme. Some varieties produce small fruit, but it is not very palatable. On the other hand, it is the cherry tree which produces the small, red fruit that is so well-known around the world. Both trees belong to the main genus Prunus, which consists of about 400 species. Prunus Cerasus is one of the species presenting edible fruit, while Prunus Speciosa and Prunus Jamasakura bloom large flowers suitable for hanami.

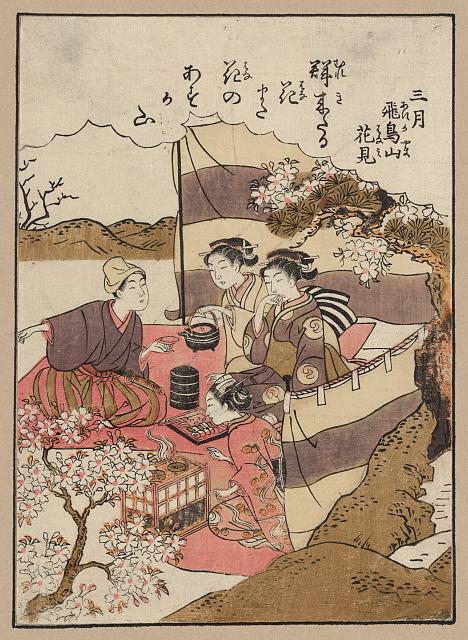

Kitao Shigemasa, Yayoi or Sangatsu, Asukayama Hanami (Third Lunar Month, Blossom Viewing at Asuka Hill), from the series Jūnikagetsu (Twelve Months), c. 1772-1776, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Ukiyo.org.

Hanami: The Beginning

The tradition of flower viewing dates to the Nara period (710-794 CE). Japan looked to China’s ancient past and cultural traditions for inspiration, while seeking to grow in power and influence. It is from this time that we first find accounts of aristocrats and courtiers gathering to read Chinese poetry. During these gatherings, they also celebrated the transient beauty of plum blossoms.

By the time Japan entered the Heian period (794-1185 CE), the term hanami referred specifically to cherry blossom viewing.

Suzuki Harunobu, Young Samurai Viewing Cherry Blossoms as a Mitate of Prince Kaoru, c. 1767, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Museum’s website.

Warrior Poets

Among blossoms, the cherry blossom,

Among men, the warrior.

During the Feudal age of Japan (1185-1603 CE), the samurai chose the cherry blossom as the flower of contemplation. This was a poignant symbol of the path to which they themselves had committed. Just as the cherry blossoms burst with life for a handful of days each spring, so was the warrior’s life intense, but short. Samurai lived by the Way of the Warrior—Bushido. And, the Way of the Warrior is death. It is no wonder that the samurai felt a deep affinity to this delicate flower and what it represented.

With the end of the samurai era, Japan entered a modernization period that saw a reinvention of the old tradition. Since the sakura season coincides with the new school year and the hiring of new employees at companies, the cherry blossoms came to symbolize new beginnings, renewal, and optimism.

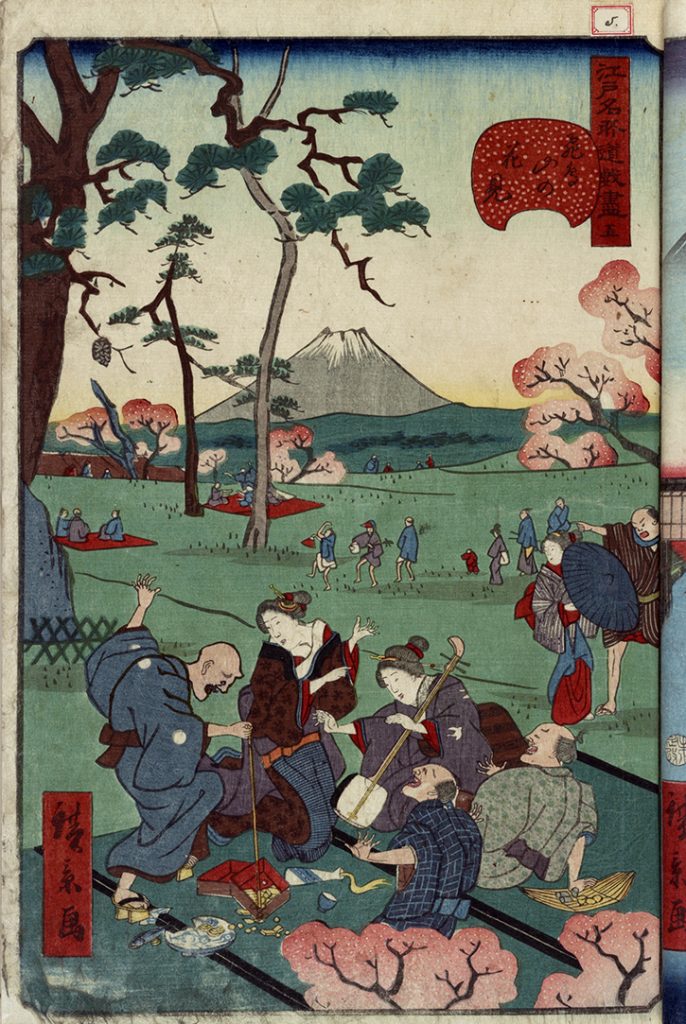

Utagawa Hirokage, Asukayama no hanami (Flower Viewing at Asuka Hill), 1859, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. ArtsMIA.

Hanami: Evolution

Sweets over flowers.

Hanami evolved to be so popular that the Japan Meteorological Agency issues bulletins to predict—and even update in real time—the Cherry Blossom Front every year. This report tracks the blooming of sakura from the south of Japan to the north, beginning in Okinawa around mid-January. The blooming generally reaches Tokyo and Kyoto around the end of March, finishing in Hokkaido towards the end of April and beginning of May.

The old proverb, “Sweets over flowers,” is now associated with hanami, with the implication that some people attend the viewing, not so much to enjoy the flowers but the parties, with all their fun and drink.

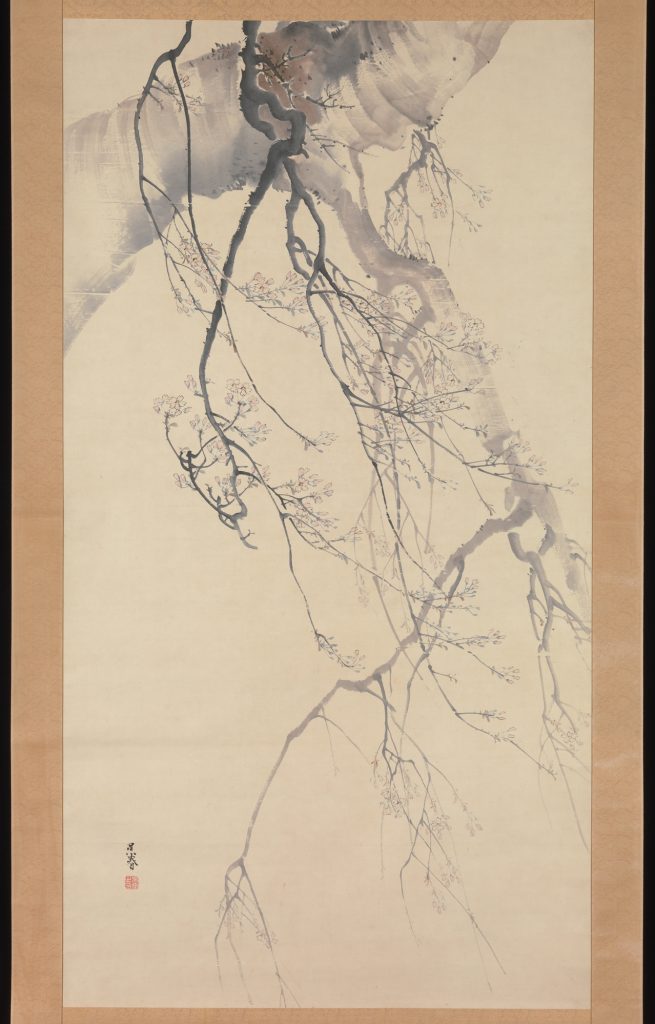

Matsumura Goshun, Cherry Blossoms, 18th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Museum’s website.

Sakura Around the World

Cherry trees thrive in many parts of the world where the climate is suitable for their growth. In 806, Japanese monk Kukai brought sakura trees to China, there known as yinghua, to commemorate his time as a student in the Qinglong Temple, in Xi’an.

Throughout the years, the Japanese have taken sakura all over the world. Individual Japanese, or Japan as a country, have gifted sakura trees to such varied places as Brazil, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, France, and The Netherlands.

The United States owes its cherry blossoms to an idea conceived by writer and diplomat Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore.

Unknown Artist, Wind-screen and cherry tree, c. 1615-1868, Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian, Washington DC, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Spreading the Love of Cherry Blossoms

After taking a trip to Japan in 1885, writer Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore tried for 24 years to convince the Office of Public Buildings in Washington DC to plant cherry blossom trees around the US capital. The first experiment planting cherry blossoms in DC was a success in 1906 when the US Department of Agriculture imported 75 trees to test their ability to adapt to the new environment.

Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore approached First Lady Helen Herron Taft, in 1909, with the idea of raising money to purchase the trees and donate them to the city. Mrs. Taft had lived in Japan and was familiar with the beauty of the flowering cherry blossoms. It was her idea to plant them by making an avenue of them. When the former Japanese Consul in New York learned of the First Lady’s plans, he suggested that his government make a gift of the trees, instead.

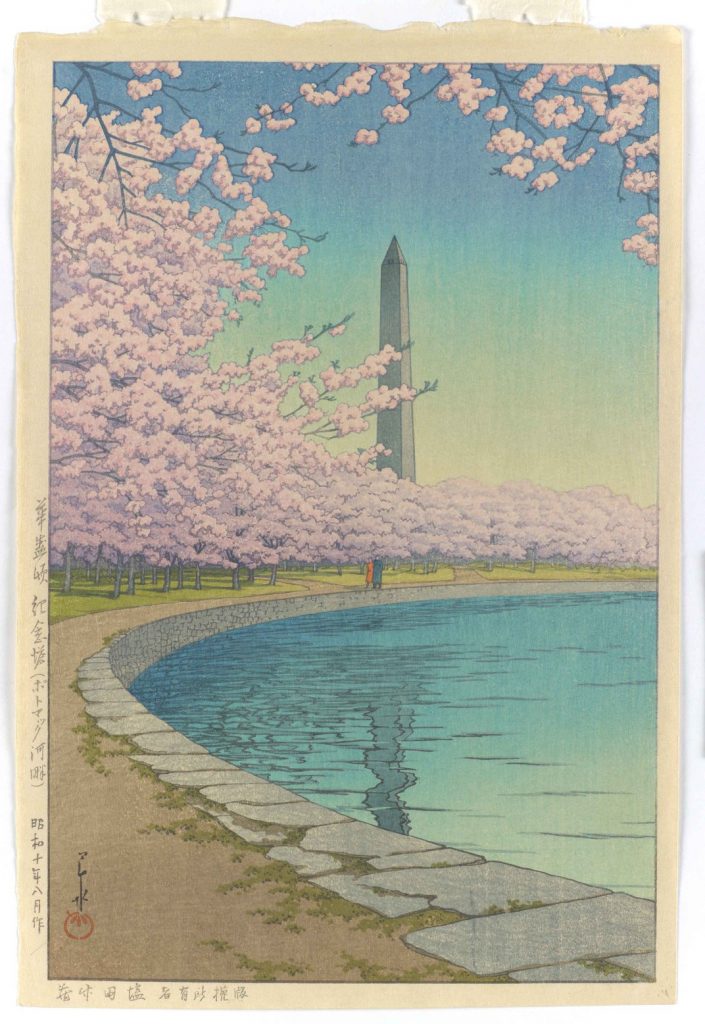

Kawase Hasui, Washington Monument (Potomac Riverbank), 1935, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, The Smithsonian, Washington, DC, USA. Museum’s website.

Japan’s Gift of Friendship

Former Tokyo’s Mayor, Yukon Ozaki, supported the gift of 2,000 cherry blossom trees to the US. Unfortunately, these first trees had to be destroyed due to disease. The Mayor sent another shipment, this time of 3,020 trees, for goodwill. These trees, comprised of twelve varieties of sakura, arrived to the United States on March 26, 1912. First Lady Helen Taft, and the wife of the Japanese Ambassador, Viscountess Chinda, planted two Yoshino cherry blossom trees on the northern bank of the Tidal Basin, about 125 feet south of what is now Independence Avenue.

Washington DC’s National Cherry Blossom Festival grew from this ceremony. These two original trees still stand several hundred yards west of the John Paul Jones Memorial, located on 17th Street, beside a plaque commemorating the occasion. In a gesture of gratitude for the gift of the cherry trees, President Taft sent a gift of flowering dogwood trees to the people of Japan.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Evening Cherry Blossoms at Gotenyama, 1831, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Museum’s website.

The Pathos of Things

So, how does an artist—a painter, or pottery-maker, a poet, or a writer—portray a moment that is not meant to last? “Mono no aware,” “the pathos of things,” is a Japanese phrase that tries to convey this feeling behind things that are not meant to last forever.

Faced with the dilemma of making enduring art from an evanescent phenomenon, artists have resorted to many solutions. These solutions range from focusing on the hanami party itself, to portraying the blossoms in all their fragility and beauty. Sometimes the blossoms are alone, sometimes in branches, sometimes surrounded by other delicate birds, insects, and flowers.

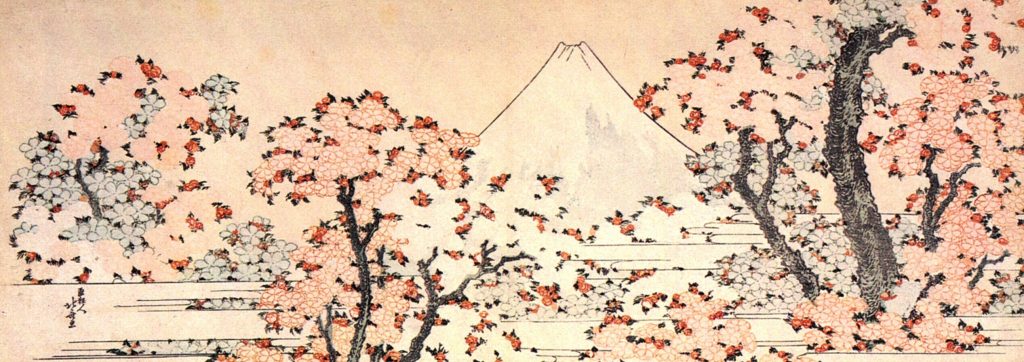

But, perhaps most interestingly, artists have sometimes placed the soft sakura beside symbols of long-enduring power such as buildings, rivers, and even the mighty Mount Fuji. By showing one next to the other, the loveliness of the sakura’s brief blooming shines the most. Without that contrast, maybe it would be impossible to appreciate the nature of the cherry blossom’s message and symbolism.

Photo by Jon Connell, Katsushika Hokusai, Mount Fuji seen through cherry blossom, c. 1801-05, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Impermanent Beauty

The snow of yesterday

That fell like cherry blossoms

Is water once again

Like the sakura’s swift blooming—in a single breath, both life and death—the world is full of contrasts in all its cycles and turns. The richness of the human experience is best measured in these cycles of contrasting phenomena. Maybe it is that dichotomy of opposites—soft and hard, fast and slow, fleeting and enduring—that makes life so rich and beautiful.

Through the enjoyment of things that are not meant to last, we allow ourselves to fully engage in life through all its facets. We embrace the contrasts and gain acceptance of the beauty of our own impermanence.

All life is an experiment. The more experiments you make, the better.

The purpose of life, after all, is to live it, to taste experience to the utmost, to reach out eagerly and without fear for newer and richer experience.