Summary

Read about the story Nicholas of Myra, the real Santa Claus, and his depictions in art—from the Byzantine empire to the modern times.

Such art not only preserved the original stories but also adapted them for successive generations, ultimately giving rise to the New World folk hero, Santa Claus. Here are examples of how this enduring story has been visually told.

1. Byzantine Era

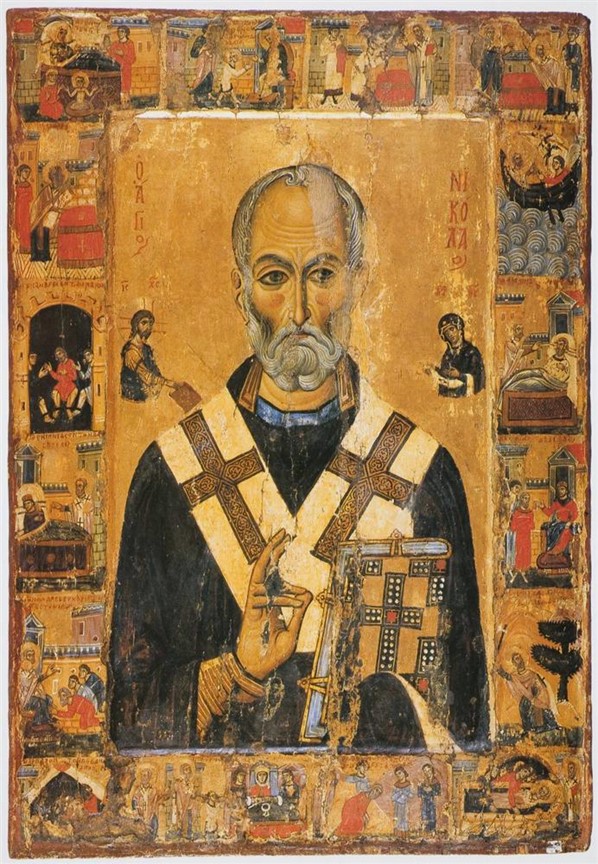

Vita Icon of St. Nicholas, late 12th to early 13th century, Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt.

Nicholas of Myra became a Christian Bishop in 317, during Roman emperor Constantine’s reign, and attained sainthood during his lifetime (though canonized officially in 1446). The earliest surviving images of him date back to the 10th century, portraying him with a furrowed brow, receding hairline, and holding the Gospel. His bishop’s stole, adorned with large crosses, and these symbols, rather than accurate portraiture, defined the St. Nicholas archetype, aiding viewers in identifying him in veneration art. The white stole, traditionally made of wool, might have eventually influenced the white trimming of Santa Claus’s suit.

Numerous tales of St. Nicholas’s benevolence exist, leading to the creation of a specific type of icon art dedicated to him—the Vita icon; literally the image of a life. In this variant, a narrative frame details life events and deeds surrounding the central figure. The St. Nicholas vita stories cover various aspects, from his precocious newborn abilities to his charitable acts as a young man, interventions to save children, experiences of Roman oppression and imprisonment, to his halting of an execution by preventing the henchman’s sword, among others.

Typical of icons, this piece is tempera on wood, with a gold background invoking infinite space and divine light. While the pose is predominantly frontal, the saint’s eyes gaze left, and the raised hand in blessing imparts a sense of movement. This aids the petitioner in feeling a direct connection with the Saint while meditating on the image.

2. Trecento Renaissance

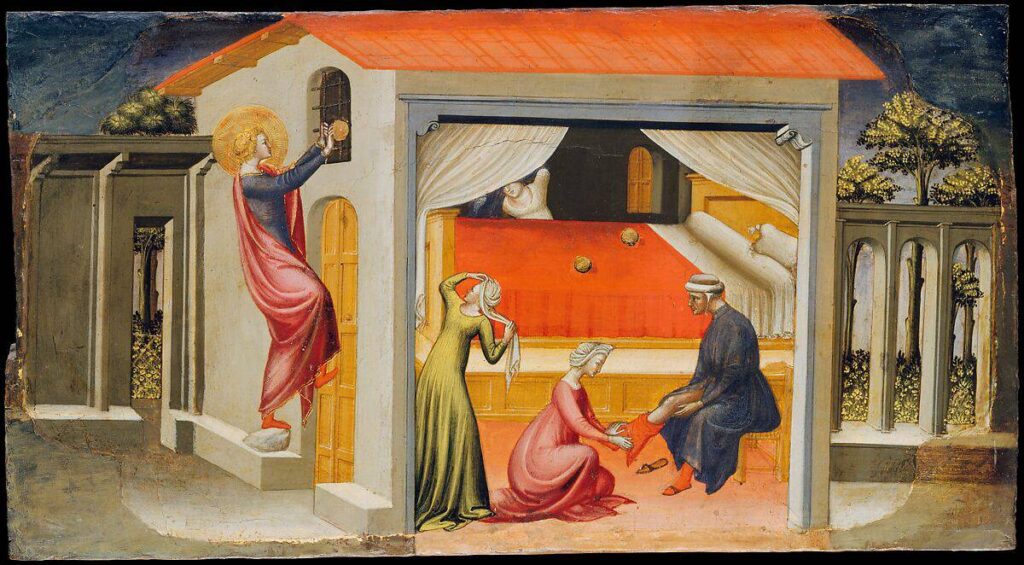

Bicci di Lorenzo, Saint Nicholas Providing Dowries, 1433–35, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Gift of Coudert Brothers.

In a popular legend, St. Nicholas is said to have secretly visited the home of poor sisters on three consecutive nights, discreetly tossing gold through their window to provide dowries. These dowries allowed the girls to marry instead of facing a dire fate, preserving their virtue. This narrative has been a favored subject for artists, exemplified in the 15th-century panel above.

This tempera on wood painting constitutes a single panel of a large altarpiece, an elaborate storytelling method akin to a stage setting for Christian mass celebrations. Similar to the arrangement in a Vita icon, multiple altar panels can convey various stories in an artistic composition.

This specific panel condenses three nights of narrative into one scene, portraying the girls and their father preparing for bed before the visits. Nicholas appears on the left side of the panel. The painting plays with time, gravity, and perspective, typical of medieval art. The sides of the building tilt toward us, providing a charming way to depict both interior and exterior scenes. The bed’s plane is tipped up, revealing the gold from the first two nights.

It is believed that the nightcap worn by today’s Santa may symbolize the nighttime aspect of anonymous giving, as practiced by this Saint in this iconic story. Despite being depicted as a young man with a bare head of golden hair, not yet a Bishop and lacking iconic emblems seen in his older visage, he sports a halo. Although he wasn’t declared a saint at that young age, Nicholas wears a halo. Since domestic homes of the time generally lacked chimneys, note that St. Nicholas delivers his gifts through a window in dowry paintings. He seems weightless, foreshadowing the flying Santa Claus, and wears poulaines, the long-toed shoes later associated with Santa’s elves. The concept of anonymous Christmas gift-giving became linked with St. Nicholas through this legend. The gold balls representing dowries may have influenced the tradition of gifting oranges, resembling the balls, placed in the shoes and stockings left out by children on the holiday eve.

3. Dutch Golden Age

Top: Jan Steen, The Saint Nicholas Feast, ca. 1668, Catharijneconvent, loan from Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Nethelands. Bottom left: Jan Steen, The Saint Nicholas Feast. Detail. Bottom right: Jan Steen, The Feast of Saint Nicholas, 1665–1668, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

The kindness of St. Nicholas sometimes got overshadowed by the lively wassailing rituals and festivities that accompanied Christmas. The Protestant Reformation in Europe, marked by criticism of Catholic practices and rejection of religious art, including Christmas, led to the outlawing of St. Nicholas by King Henry VII in England.

In Holland, Sint Nikolaas, or Sinterklaas, rode on horseback through the sky the night before his feast day. Children placed shoes by the hearth, hoping for them to be filled with gifts. To keep Christmas alive during iconoclastic times, a certain amount of strategic planning was helpful. The genre painter Jan Steen depicted the morning after the saint’s visit, where, much like today, a family enjoys the children’s delight. Despite being Catholic, Steen did not paint St. Nicholas but focused on the celebration. Additionally, to align with the mood of the time, Steen created two versions of The Saint Nicholas Feast—one believed to be for a Catholic audience and the other for a Protestant one. In the Rijksmuseum version, the central daughter figure clutches a religious gift—a St. John the Baptist doll. In the Catharijneconvent Protestant version, the gift is a round piece of gingerbread.

4. French Romanticism

Gustave Courbet, Saint Nicholas Reviving the Little Children, 1847, Musée Courbet, Ornans, France.

Gustave Courbet would one day throw aside traditional subject matter, academic conventions, and romanticism to radically paint the unidealized and ordinary, life on life’s terms. However, before he emerged as this innovating realist, he worked as a religious painter in the departing romantic style.

His Saint Nicholas panel was his first commissioned work, for a local church. All his art studies are there–the atmospheric perspective background, the heavenly vault, the popular saint in his bishopric iconography, the allegoric story telling. Perhaps the first glimmering of Courbet’s move away from this style towards his innovations in realism is the identifiable portraiture of his model, who was a close friend.

5. Russian Realism

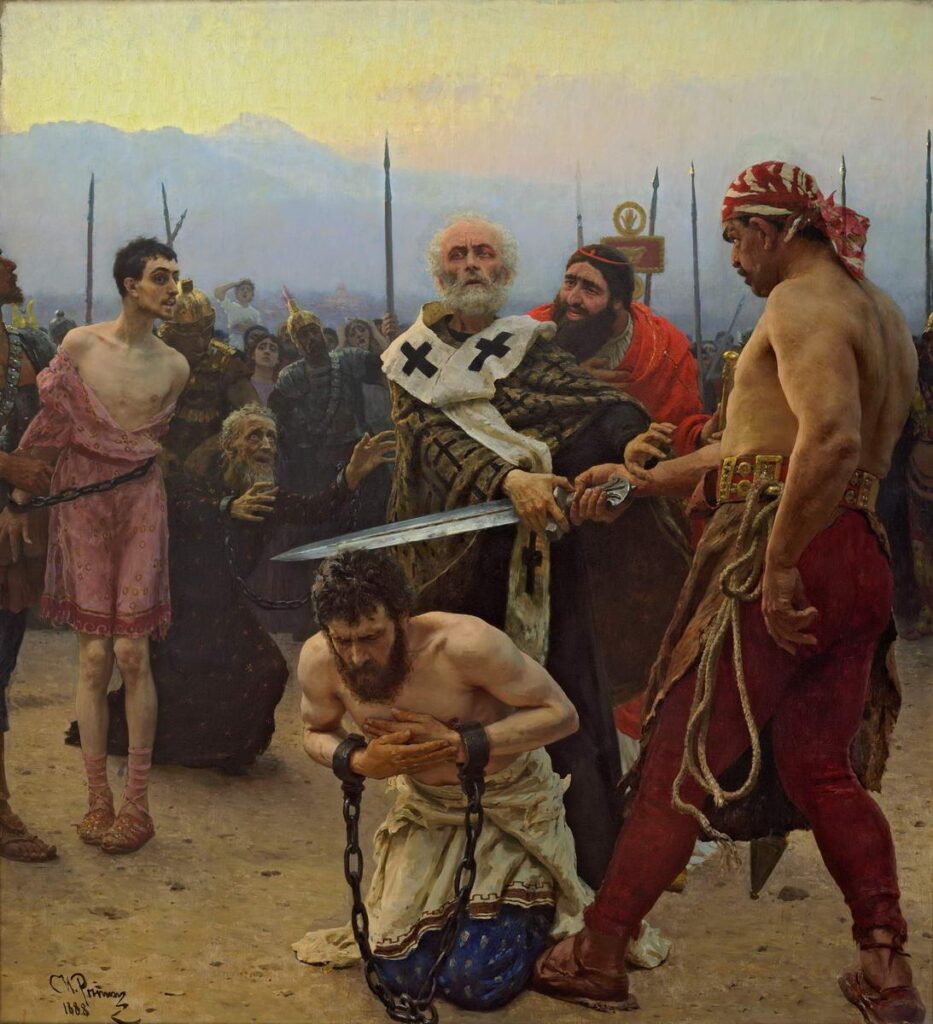

Ilya Repin, St. Nicholas of Myra Saving Three Innocents from Death, The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Wikipedia Commons (public domain).

Humanism, reformation, the rise of the middle class, all sorts of forces helped European art move away from religious themes and their romantic and mystical methods. There was no need for gold aureole, floating figures, or other means of depicting the spiritual when artists wanted to capture the everyday, subtle forces of nature, the preeminance of the ordinary, and man as his own spiritual essence. Thus it is interesting when an artist creating new naturalistic painting methods still wanted to paint a religious theme. How did this marry?

Ilya Repin was such an artist. He painted en plein air, copied Édouard Manet, and developed a realistic style so detailed that it has been considered hyper-realistic. Yet, he had started out as an icon painter, and continued to tackle those religious themes even while working in the new ways. His masterpiece, St. Nicholas of Myra Saving Three Innocents from Death, tells a favorite legend of the Saint as if the man himself stepped out of a Vita icon. The familiar iconography is all there–wrinkled brow, a receding hairline, and bishop’s wool stole in white with large crosses. He is rigid and frontal, and sure enough, his eyes glance to the side. But there is no golden nimbus, the setting is as if en plein air. The work is relatively monumental, at 7-foot by 6.5-feet (213.36.by 198.12cm). Its painterly space is foreground, middleground, background, and each of those layers is made of humanity. The faces carry emotional energy, and the composition spirals about the miracle worker in a way that multiplies this energy like an unseen force. Upright lances in the crowd evoke the three crosses at Calvary, and we again have three men facing execution. This may not be a secular Santa Claus, but he is a man among men, we believe he will bleed.

6. The New York Knickerbocker

Robert Walter Weir, St. Nicholas, ca. 1837, Smithsonian American Art Museum,Washington, DC, USA.

Like Repin, artists in America had also traveled to Paris to learn modern techniques, returning home to invent an art of power and drama. Robert Walter Weir is loosely associated with this group, the best of which were collectively dubbed the Hudson River School, but he may be known for his portraits and interiors as much as his landscapes. He was a member of the Knickerbocker gentlemen’s club in New York City. The club was named for a Washington Iriving fictional narrator, Diedrich Knickerbocker. Being a religious man, Weir may have noticed the homophonics of this made-up word to St. Nick. Weir’s genre painting of the Saint shows a squat man who looks nothing like his bishopric iconography. Instead, it is thought to capture a description of the Saint that Diedrich Knickerbocker gave in Irving’s satire, A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, as a jolly old bourgeois Dutchman, nicknamed Sancte Claus. Irving’s story is considered to also be the inspiration of the poem, “A Visit from Saint Nicholas”, which further transformed the Saint’s appearance, and his nickname, into that of a jolly round elf, by influencing Thomas Nast.

7. The Gilded Age

Thomas Nast, Merry Old Santa Claus, 1881, Macculloch Hall Historical Museum, Morristown, NJ, USA.

Because his story is popular and tied to an annual holiday, St. Nicholas imagery emerges anew with each innovation in narrative art. During the US Civil War, a new such media emerged—illustrated news magazines, which published wood-block prints alongside the news of the day. This meant that the Civil War and Reconstruction era were well documented, firstly because the engravings were often based on photos, but also because satirists had a wide forum for political cartoons.

Thomas Nast, a Bavarian immigrant to New York, was the pre-eminent satirist of this new media. He opposed slavery, influenced elections, and revealed army-camp life through his satirical engravings for Harper’s Weekly, A Journal of Civilization. It was in an 1863 army camp where Nast first included Santa Claus—allegedly borrowing the imagery from the popular poem, but Nast is also thought to have modeled the character on Bavarian traditions and on himself: a rotund, bearded man. He drew a jolly elf, and dressed him in the Union flag, gifting toys to Civil War servicemen, including a lynched wooden Jefferson Davis doll. Nast created Santa cartoons annually for Harper’s Weekly over 30 more times.

It was his 1881 “Merry Old Santa Claus” that squarely moved the iconography of the man to the apple-cheeked, beneficent, white-trimmed wool-suited bowl of jelly with a big gold buckle. The belt is from the army uniform, and the sack of toys on his back is an army rucksack–Nast used the gifting character to illustrate his campaign promoting fair wages for soldiers.

8. Modern Art

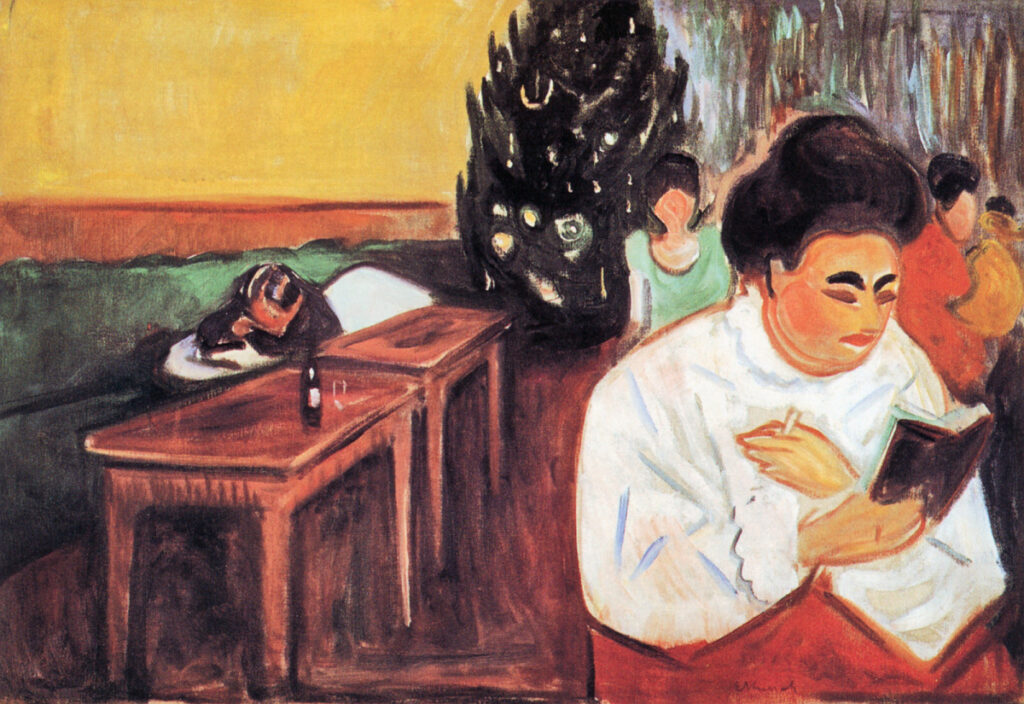

Edvard Munch, Christmas in the Brothel, 1903/04, Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway.

Modern art moved away from allegorical topics, and St. Nicholas is largely absent from non-church masterpieces of the modern period. There is one potentially intriguing exception. While there is no reason to think that Edvard Munch had the St. Nicholas story in mind for this painting–it is simply an illustration of his visit to a brothel–he nonetheless created, likely without intending to, an inverse of the St. Nicholas story of saving three women from prostitution by gifting them dowries.

The painting works remarkably in this reading, it shows what might have been if the three girls were not gifted gold. The three women here are prostitutes. They have decorated for Christmas, as shown by the cropped central background tree, awaiting St Nicholas gifts. It is not their Papa sleeping in a bed, but the artist an inebriated customer on the sofa. The foreground woman is probably marking her little black book, not reading the Gospel. Where St. Nicholas iconography has him holding the good book in his left hand and blessing the viewer with his right, this woman has reversed the hands–her blessing cups her own heart, as well as a pen. Her white and red outfit is not vestments. Her halo is a bouffant. The infusion of gold is now simply a band of ochre wall paint.

Munch was raised in a fundamentalist home, and he sought to instead give his art a human focus. Yet despite this, or perhaps because of it, his masterpiece themes–of love and death, vital dread, the mystery of life–are the themes of religion.

9. Post-War Period

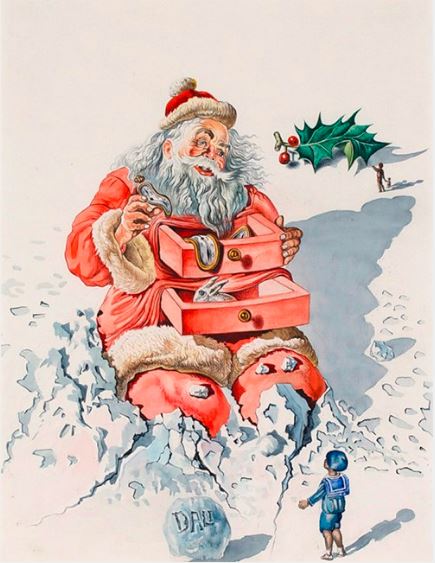

Salvador Dali, Santa with Drawers, 1948. Hallmark Card Collection.

Today, the transference of St Nicholas to Santa Claus in art is complete. Santa’s image is used in advertising, parodies, and holiday décor. He is the subject of Christmas cards, which emerged as postcards in the 1840s as another form of visual storytelling–a place where families can write their own stories of the year to a pre-purchased illustration. In 1915, the Hall Brothers company, later Hallmark, created the fold-over card familiar today, which gives folks a little more room in which to narrate. Hallmark solicits work from artists to illustrate their annual cards, and in the 1940s, this included Salvador Dali.

Dali had been a leader in the 1920s Surrealist movement, an art that sought to work from the unconscious mind, and break from the social and natural subjects of modern artists. His later period, from the 1940s onward, has had some criticism for recycling his surrealist-phase imagery for commercial purposes. This could be said of the above Christmas card, which imbeds Santa Claus with the anthropomorphic chest of drawers symbolism he had previously explored, and places in the drawers his melting clock and rabbit motifs. But setting the criticism aside, it can be seen that the card is quite thought provoking–the commercialized Santa, on a card sold for profit, is gifting nonmaterialistic things–the passing of time, rebirth, and memory. The message is worthy of a Saint’s story. Interestingly, the atheist Dali re-converted back to Catholicism the following year, and many of his later paintings powerfully explore themes of the religion.

10. Ground Zero

Father Loukas of Xenophontos, The Titular Icon of Saint Nicholas in the Shrine at Ground Zero, 2020-2022, St Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, New York City, NY, USA.

The St Nicholas Center knows of 6,500 churches throughout the world named for the popular saint. One of these, The St Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, was destroyed on September 11, 2001. Originally founded by Greek immigrants to NYC, a replacement building was opened in 2022. It included the additional purpose of providing a secular bereavement center.

The new building interior is a colorful built Vita of the saint. The large central icon of St Nicholas greets entrants. It is in the familiar rendering of the saintly bishop’s iconography, codified so very long ago. Its return is as if to say, the church building may have been destroyed, but the beliefs, history, and belovedness for this benevolent holy man is untouched and evermore.

Jaroslav Čermák, St. Nicholas, Galerie Art Praha, Prague, Czechia. Wikimedia (public domain) Detail.

Torture, Iconoclasm, politics, and tragedy have not been able to stifle the human urge to love, give gifts, and care for each other. The ethos of St. Nicholas/Santa Claus and of good people everywhere, is everlasting. The muscle of art to explore the nature and struggles of life is as strong as ever. We wish the Peace of the Season to all.