5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Art itself is often closely associated with some form of solace or peace. Though not all art exists to establish in oneself an inner tranquility, many find that it has a soothing or therapeutic effect that seems to translate all human boundaries. W.B. Yeats, an Irish poet from the late 19th and early 21st centuries, pondered this solace-seeking. He, too, wanted peace and dreamed of an escape, a place far removed from the bustle of everyday life.

He called it Innisfree, an island in the middle of a lake that he immortalized in an 1888 poem (below). “And I shall have some peace there,” he pondered, imagining nights spent in the center of a pool of placid water, the midnight aglow around him.

Yeats’ yearning for Innisfree was shared by a couple from New York State by the names of Walter and Marion Beck. In the 1920s, they settled in the town of Millbrook and began planning their own private Innisfree nestled in the midst of their country estate.

Walter was himself an accomplished painter and former professor at both the Art Institute of Cincinnati and the Pratt Institute in New York. At one point in his solo career, while experimenting with the use of new materials, he developed a method of tempera painting that used starch as its base.

This was to be Walter’s painterly legacy; he found the method positively freeing, leaving “nothing to oppose an artist’s flow of ideas or emotions.” The first to develop the starch-film medium, he went on to publish a book on the subject. He would later accredit his developments in the process as aiding his growing instinct for landscaping.

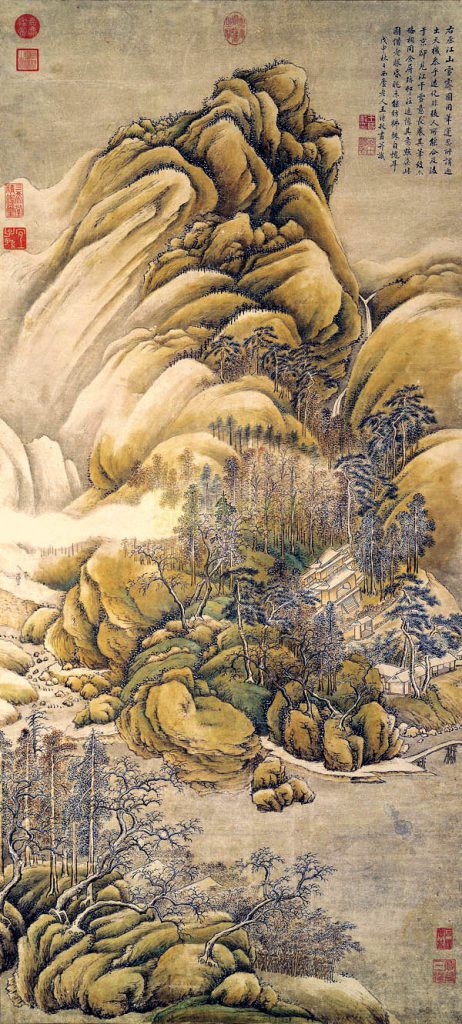

But it was Walter’s interest in Asian art that would prove to be his major influence on garden design. He and Marion became fascinated by the poems and paintings of Wang Wei, an 18th-century Chinese statesman. Wei typically painted natural subjects, specifically bamboo, mountains, and streams. He liked to create visual focal points that drew the eye, which translated into his gardening.

Walter coined Wei’s individual, harmonic compositions “cup gardens,” each contained in its own space and unique to that particular area. They became the building blocks on which Innisfree was designed, each garden reliant upon the natural characteristics of its contents – the shapes and sizes of rocks, topography, and foliage – to determine the overall configuration.

This practice is outlined in an 11th- or 12th-century text known as the Sense Hisho, or Secret Garden Book. It contains all methods of traditional Japanese garden design up until that point, and had it not been for a landscape architect named Lester Collins, it would never have reached the United States.

In 1954, as a Fulbright Scholar, Collins went to Japan. There, with the assistance of a native, he translated the 1,000-year-old manuscript into English. As the first to attempt such a feat, he had access to the book before any other Westerner, allowing him to capitalize on its until then unknown secrets – and test them out at Innisfree.

It was Collins who implemented a wild, organic approach to the design of Innisfree. The Becks met Collins in 1938, and from then on out he devoted 55 years of his life to the garden.

A strong proponent of modernism – which, in landscape architecture, preferred a natural functionality to a man-made, aesthetic form – Collins allowed the land and its contents to speak for itself rather than fabricate an “American” garden. Symmetry for the sake of symmetry was done away with, leaving only a meandering path down which one would walk from “cup to cup.”

Simplicity and a reduction of form in Asian garden design are meant to be meditative – to create an environment in which the forms before one’s eyes are so basic, so easy to take in, that one must ruminate on them to derive deeper meaning. Philosophical thought becomes inherent, and a stroll through the garden becomes an enlightening journey.

At Innisfree, the undulation of the land and flow of the garden around the central pond allows one to breathe, to meditate on life and its workings – precisely what Yeats wanted out of his own Lake Isle. Coincidence?

Walter drew heavily upon his compositional conventions as a painter when designing the garden, and in this fashion, one travels from vignette to vignette as though walking through an art museum. Certain parts isolate one more than others, just as a particular painting or statue might catch the eye and hold one’s attention, seemingly silencing the rest of the world.

However, at Innisfree; the isolation is more apparent in that one is occasionally cut off entirely from the world around by shrubbery or rock formations. It quite literally separates one from other visitors on islands amidst the grass. It’s as if each cup garden is its own Innisfree isle, a whole park of Yeats’ dreams.

Today, Innisfree is run by an educational foundation that promotes the study of garden design and the preservation of landscape architecture. It not only maintains a now public gem of eastern-inspired American gardening, but it inspires new generations with its timeless mystery, its humbling beauty that is at once overwhelming and, piece by piece, quite manageable.

It’s a place that resounds with everyone at “the deep heart’s core.”

By William Butler Yeats:

“I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.”

This poem is in the public domain.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!