The National Gallery in London: Where to Start?

Having lived in London for the past three years as an art lover, I have had more than my fair share of questions about where to “start” at the...

Sophie Pell 3 February 2025

Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities at the Morgan Library and Museum (June 18 through September 26, 2021) looks back at the first 15 years of Shahzia Sikander’s career. Focusing on the period between 1988 and 2003, this exhibition traces the artist’s journey from Lahore, Pakistan, where she was a student of miniature painting at the National College of Arts, to her graduate studies at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), followed by a residency in the CORE Program of the Glassell School of Art at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and eventual move to New York City in 1997. This exhibition was organized by the RISD Museum in collaboration with the Morgan Library and Museum and curated by Jan Howard who co-edited the exhibition catalog with Sadia Abbas.

During this fruitful period, Sikander achieved international acclaim for her mastery of Indo-Persian miniature painting. Breaking through this very old practice to develop a visual idiom of her own, Sikander has simultaneously honored and expanded miniature painting. Extraordinary Realities is a stunning overview of a groundbreaking journey that began three decades ago with one of the most revolutionary and important artists of our time.

While a student at the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore, Shahzia Sikander studied under Bashir Ahmad, the professor who revived and condensed a miniature painting curriculum into a two-year program. A rigorous painting tradition that had been passed down through generations of court painters across South and Central Asia, miniature painters spent many years learning and perfecting their skills in workshops that, by the mid-20th century, had almost all but faded away. With over a decade of learning from one of the remaining few practitioners of miniature painting, Ahmad adapted a precise set of knowledge and techniques into a painting program that attracted Shahzia Sikander, one of his earliest and most prized pupils.

The demanding process involved in the making of a miniature painting cannot be underestimated. There are a number of early examples in this exhibition that establish Sikander’s technical proficiency. No easy feat, the drawn-out process required to create these small and labor-intensive paintings involves careful preparation of the paper, the painting’s surface, and the paintbrushes as well as the deliberate and slow application of paint to gradually build up the images.

The contributors to the exhibition catalog discuss the art of Sikander in ways that deviate from the reflexive and suffocating narratives that had developed around Sikander’s art in the late 1990s-early 2000s – the most popular being that of the oppressed Muslim woman rebelling against tradition. Rutgers University professor Sadia Abbas referred to the “troubling discursive loop” as placing Sikander “within the preferred American grid of escaped Muslim female immigrant, redeemed by a liberatory United States, who is meant to be grateful according to a certain script.” Her discussion of Sikander’s art is based on the understanding that this story cannot be simplified as one of “immigrant redemption or diasporic exile.”

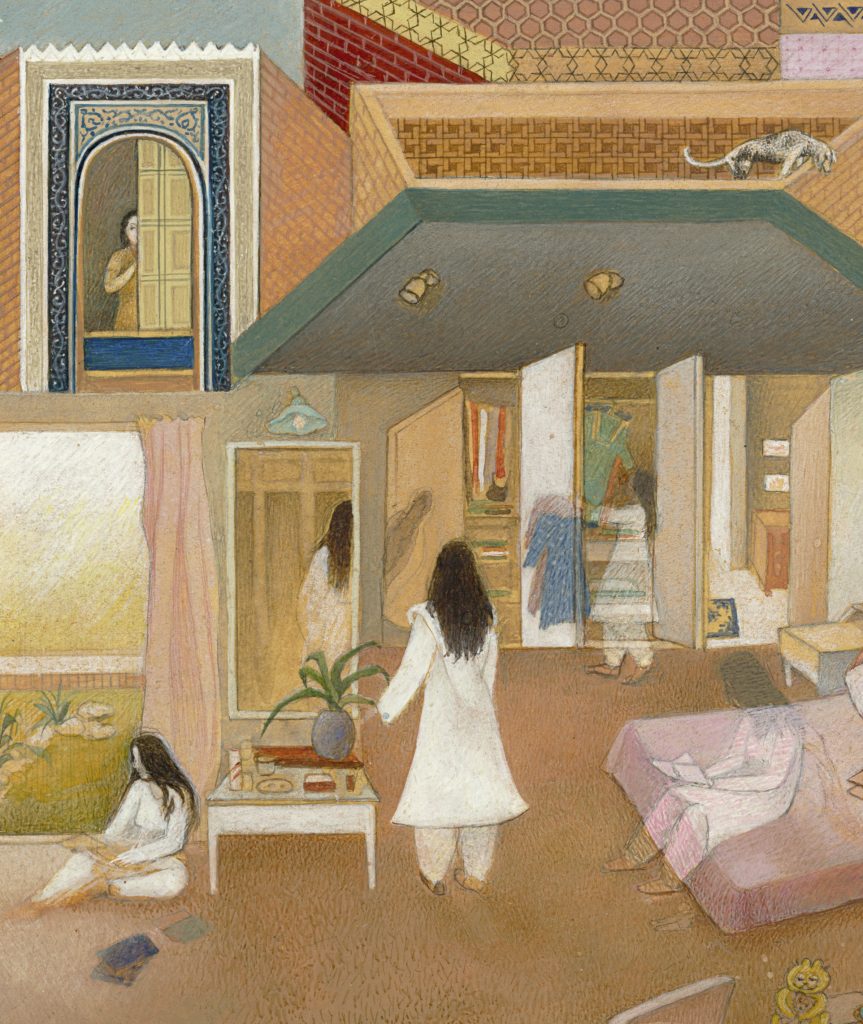

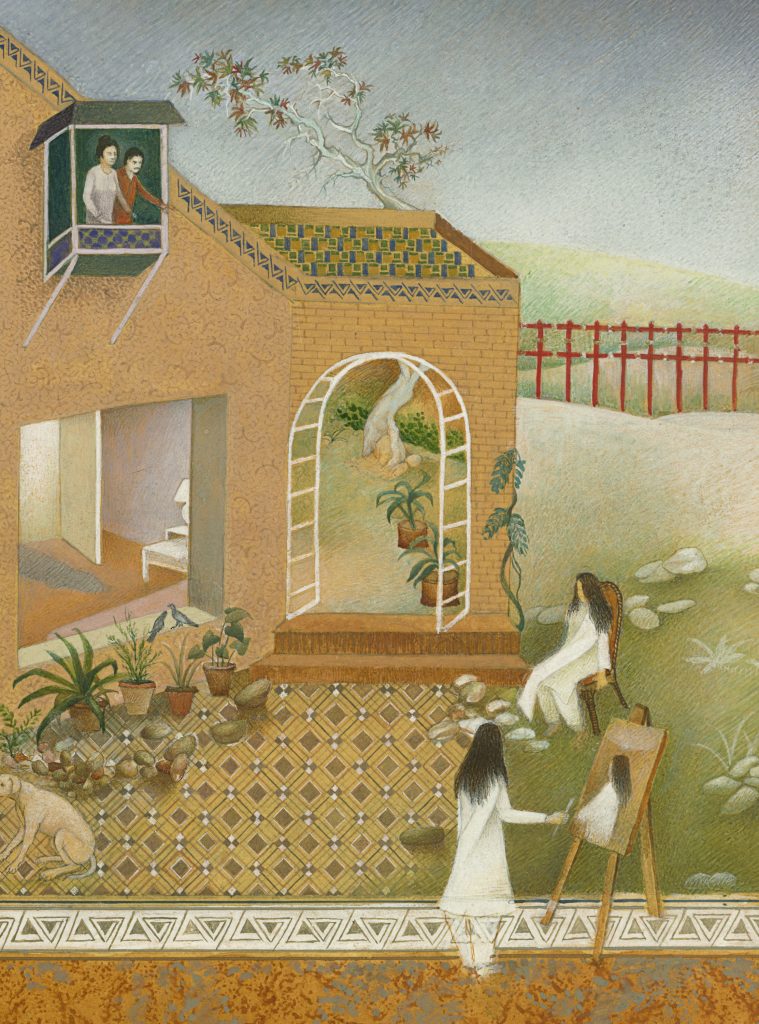

The Scroll (1988-1990) is Sikander’s college thesis, a masterpiece for which the artist received the highest honors at the NCA as well as recognition among the local art community and across various Pakistani media outlets. This work shifted from the single page format of the illustrated manuscript to the elongated picture plane of a scroll where domestic scenes of the artist and her family inside of her childhood home unfurl horizontally. The artist is the female figure in white, variably translucent and opaque, and seen numerous times throughout either moving around the other members of her household or engaged in solitary activities such as painting or reading. The figure of the artist is the central subject of this painting and although she is immersed in this setting she seems disconnected from the others. In The Scroll, the artist wielded her technical strengths to realize not only a complicated and tight composition but one that is activated by the psychological undertones of a family dynamic.

In her essay, Abbas locates in The Scroll the origin of three trajectories that have flourished throughout Sikander’s career. The first being representations of women that do not shy away from the monstrous or grotesque in an ongoing contemplation and critique of the female, femininity, womanhood, and all its complexities as applied from the outside and experienced from the inside. The second is the interplay of scale, time, and space as seen in the tightly packed recreation of Sikander’s family home. And the third one “pushes against the epistemic dominance of the West by describing the world in a visual idiom that has its origins in the very spaces subjugated and looted by colonialism.”

The refreshing insights of the beautifully illustrated exhibition catalog plus the rare opportunity to see, for the first time, in person, some of the most reproduced and discussed artworks during the artist’s ascent is nothing short of a comprehensive (re)introduction to the art of Shahzia Sikander for those of us who have been following her career closely and for those who are seeing this work for the first time.

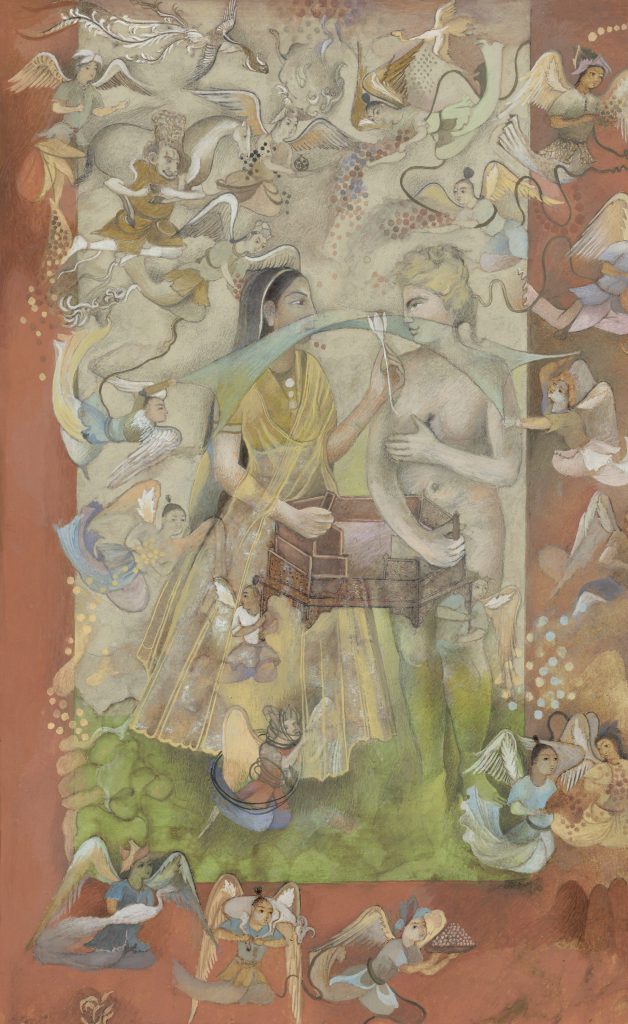

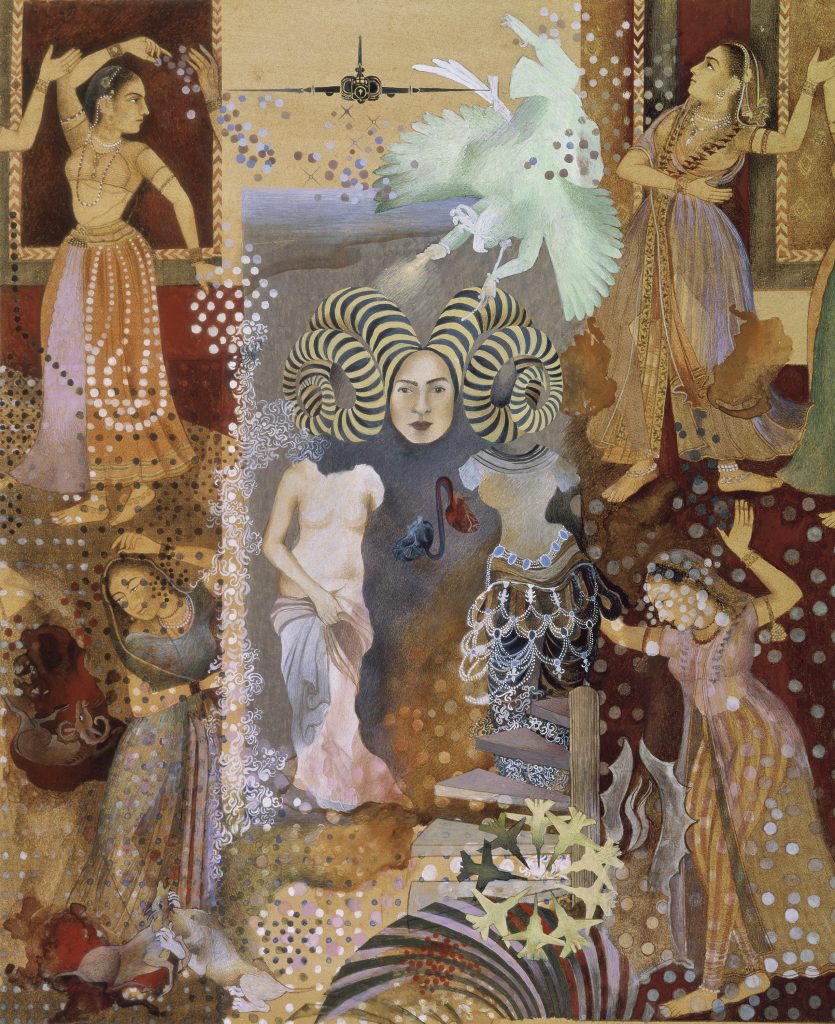

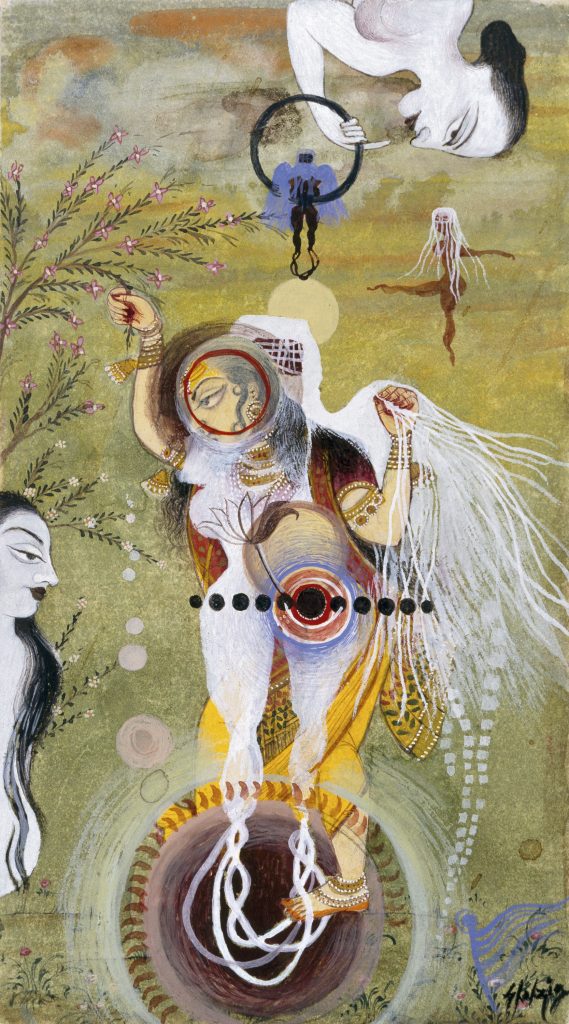

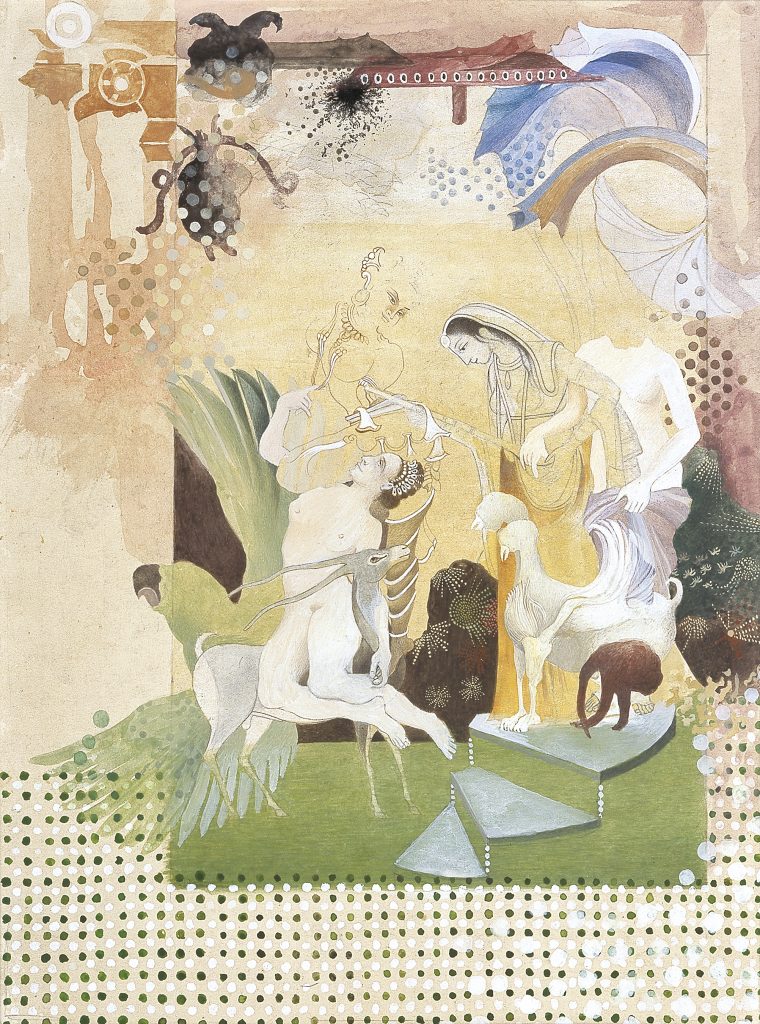

The 1990s witnessed some of Sikander’s most powerful breakthroughs. A more personal and signature style emerged with the appearance of invented forms and the integration of abstract motifs within the luscious infrastructure of miniature paintings. A proliferation of female figures extracted from a wide range of art history sources was unleashed, many borrowed from the traditional miniature paintings of South and Central Asia. Pleasure Pillars (2001) exemplifies the intricacies of an epic vision realized within the tight spaces of a miniature painting. Overlapping or isolated figures inhabit undefined spaces embellished with abstract patterns, rich swaths of color, and other fine details that are disorienting yet engaging.

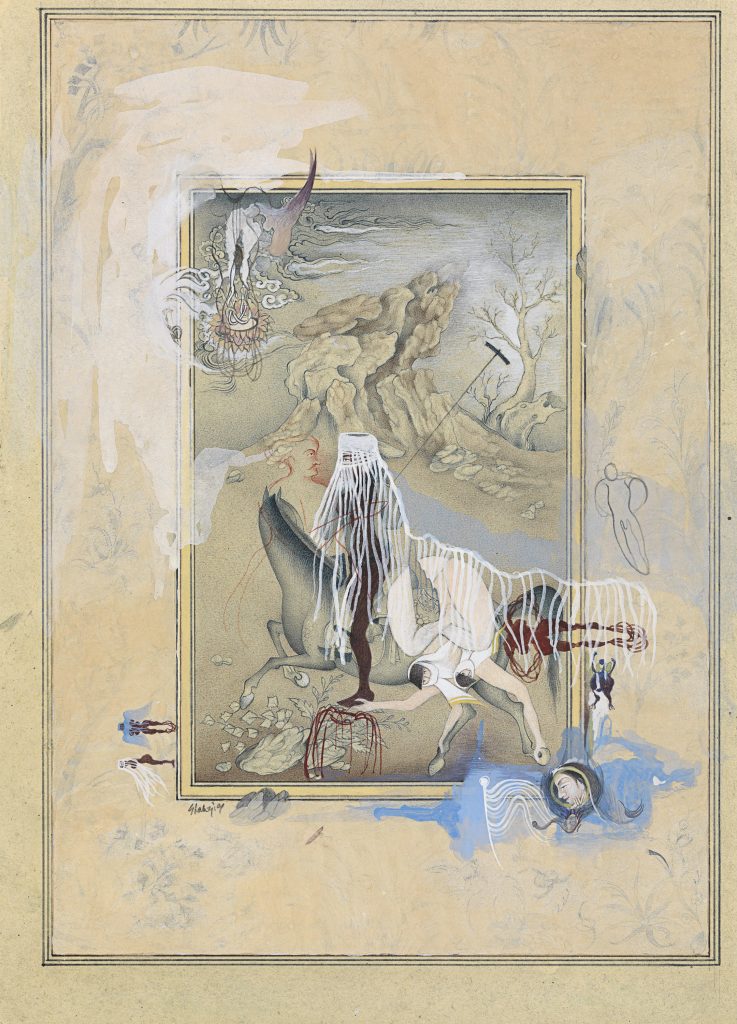

One of the most compelling forms to have emerged during this period is a shape-shifting female silhouette that Yale professor Kishwar Rizvi describes as a “biographical device, critique of the medium, avatar of disruption that entirely subverts the very history of illustrative painting.” Examples of such include a multi-armed floating female warrior wearing a white veil in Hood’s Red Rider (1997), a seated silhouette on horseback ensconced by a shredded white veil in Who’s Veiled Anyway? (1997), and a central silhouette superimposed with another female figure in Uprooted Order, Series 3, No. 1, (1997). In addition, are smaller versions of this silhouette, a constant presence throughout that quietly amplifies the series of ruptures detected throughout these works. The accentuated breasts and hips, ribbons in place of feet that connect the legs and sometimes the arms, translucent veils in place of a face, or the absence of a head altogether are some of the trademark characteristics of this favored and recurrent image.

New York University professor Gayatri Gopinath explains that “Sikander demands that we understand ‘tradition,’ ‘culture,’ and ‘identity’ as impure, heterogeneous, unstable, and always in process.” During this early period, the artist created her own visual language that has morphed and evolved over the years within and beyond miniature paintings. Rizvi asserts that “Although her paintings certainly reference Mughal art, they dig deeper into her own personal life and offer commentary on issues that are of significance to her.”

Given the scope of experimentation happening within the framework of miniature painting, it is of no surprise that the artist ventured into large-scale installations and digital animations. When Sikander’s career took off in the mid to late 1990s, the artist took advantage of opportunities to show her work in institutions where she had the freedom to paint directly on the walls. She created layered murals through the addition of illustrated strips of translucent yellow drawing paper that were suspended from above and hung at varying lengths. Actual layers in space and monumental in size, these installations daringly broke away from the scale and specialized techniques of miniature paintings and provided pathways for the artist to further experiment with an evolving visual idiom.

For this exhibition, Sikander created Epistrophe, an original and awe-inspiring recreation of such installations from 20 years ago that brings to life a wondrous shift in scale. Upon entry to the main gallery, visitors are welcomed by a section of the wall covered with narrow rolls of paper of varying lengths, some running from the ceiling to the floor, several layers deep and painted with patterns of recognizable abstract motifs from earlier works. This most recent spatial intervention, completed in just a matter of days, gives visitors to this exhibition the chance to experience the richness and vibrancy of earlier installations, an aspect not easily relayed in photographs documenting these site-specific installations from 20 years ago.

An abstract pattern floating around Epistrophe is also seen in one of the artist’s earliest digital animations, SpiNN (2003). Presented on a small screen, the backdrop is a bright and detailed depiction of a Mughal throne. This space is invaded by a swarm of gopis, the female attendants to the Hindu deity Krishna. Their hair detaches from their bodies which fade away and the remaining black forms swirl into a flock of birds. This move towards digital animation at the tail end of this 15-year retrospective was just the beginning. Sikander recently unveiled animations of monumental proportions that filled entire rooms and engulfed the viewer at the Sean Kelly Gallery this past November.

Maintaining a close engagement with her own past through a process of digging around her own visual idiom, Sikander is continually expanding her artistic journey and challenging herself to experience the true depth of her practice. A final example of the artist extracting from her own image archive is the sculpture Promiscuous Intimacies (2020), placed in the center of the entrance hall, just before the main gallery of this exhibition. Sikander’s past and present are just as entwined in this sculpture as are the females of this two-figure composition based on a drawing that first appeared in the watercolor Intimacy (2001). This is an erotically charged moment between a seated woman, copied from Agnolo Bronzino’s sixteenth-century painting Allegory with Venus and Cupid, and another woman mounted from above but only partially drawn in the 2001 watercolor that was based on a dancing Indian sculpture from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Brought into the third dimension and fully realized two decades later, Promiscuous Intimacies points to the past and present of the artist’s journey into the extraordinary realities of Shahzia Sikander.

Works Referenced

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!