5 Contemporary Women Artists from Latin America You Need to Know

When we speak about contemporary art in Latin America, women artists are at the center stage. Working around various mediums and highlighting themes...

Natalia Tiberio 16 December 2024

14 October 2024 min Read

Along the Ucayali River of Northeastern Peru, women from the Shipibo-Conibo villages have been composing striking, geometric designs to cover pottery, woodcarvings, and textiles for over 1200 years. Each woman must design her own pattern that both expands upon the work of her ancestors and remains faithful to a highly traditional style. She will then use that pattern to decorate the crafts she makes throughout her life.

The Shipibo people are remarkable because they are not only one of the few Indigenous groups where women are the primary artists, but they also have an elaborate rite of passage ceremony marking women’s transition into puberty, as opposed to a more common male-based celebration.

Based along a southern tributary of the Amazon, the Shipibo-Conibo Indigenous people live in small villages of about 100-300 people. Over several centuries, the Shipibo and Conibo peoples gradually amalgamated into one group, first by living in the same villages, adopting each other’s customs, then transitioning to the same language, and eventually intermarrying. They have become famous for their unparalleled pottery, which can be found in some of the world’s most prestigious museums.

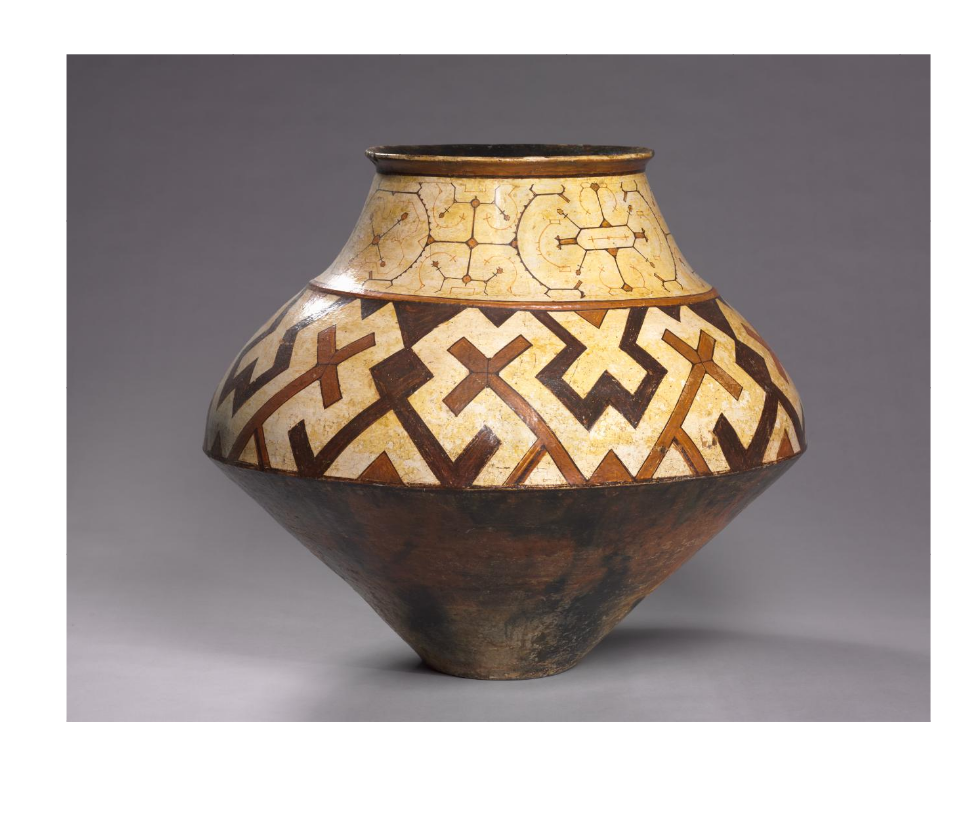

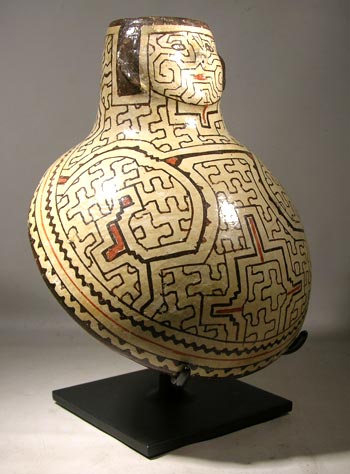

Examples of Shipibo pottery date to as early as 800 CE. Their geometric patterns (Kené in the Shipibo language) have gradually changed since then. However, most timelines of the pottery’s development remain purely a product of stratigraphy, rather than more precise, absolute dating methods. Women remain exclusively responsible for any artwork produced by the villages, with the exception of art produced for tourists. Shipibo pottery took thousands of years to develop. Eventually, generations of experimentation allowed the artists to perfect the thinnest and largest coil-based pottery of any Indigenous group in the Americas.

Women primarily work on the pottery during the region’s dry season spanning roughly from June to August. The first step of the process is to gather both dark and light clay and then knead the two types together. The artists then roll the clay into small snake-like lengths. They stack these tubes of clay into small layers, shaping and joining them while slowly building up the walls of the jar. After a few coils are added, they must leave the pot to dry out in the sun before more can be placed on top, to prevent the entire shape from collapsing.

After they have constructed the basic shape, the women use a large seed to carefully scrape off excess material and polish the jar as they go. This is necessary to achieve the extreme eggshell thinness characteristic of Shipibo pottery. Once they finish polishing the surface, they move on to decoration. First, the clay is coated in a thin slip. Next, they use a small brush, often made from their own hair. They usually start with the design near the top of the ceramic. They paint the thickest lines first, peshtin, before adding the thinner, wirish, which parallel either side. Finally, they add thick borders, quenea, on the top and bottom of the pot.

Once they finish decorating the object, it is finally ready to be fired. They place the delicate jar inside a metal pot, cover it in ashes, and then place the whole thing in the middle of a bonfire. After the pots are fired, the final step is to cover the pottery in a fine resin that seals, waterproofs, and heightens the colors of the final vessel.

Shipibo pottery comes in several different shapes. The largest is a Chomo, a rounded pot with a narrowing net that is typically able to hold 25-50 liters. There are both Ainbo Chomos, which are used as water vessels, and Masato Chomos, beer jars. Shipibo artists also create eating and drinking bowls, known as Quëncha and Quënpo.

Some debate persists about what the Shipibo designs are intended to represent. While researchers Peter Roe and R.L. Bunzel claim that the designs have no meaning whatsoever beyond aesthetic decoration, other scholars have written that they may represent constellations. Peter Roe also proposed that the crosses common on Shipibo designs may originate from the missionaries that began interacting with the village around the 16th century. The villagers themselves adhere to a strict practice of silence about their pottery or the designs they have chosen to decorate them with, potentially out of a strong custom of modesty. Whatever the reason behind their designs, Shipibo women have created some of the most sought-after folk art designs in the world.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!