Marian Henel—Tapestries and Madness

Marian Henel’s tapestries are huge. The largest one measures over 6 m in length and 3 m in width (19 ft. 8 in. by 9 ft. 10 in.). Created in the...

Zuzanna Stańska 25 November 2024

Dia De Los Muertos is celebrated every year across Mexico. A far cry from the Western commercial horror-fest of Halloween, it is a glorious celebration of life and a time to remember and honor the dead, with temporary altars erected in loving memory. On this occasion, we present to you skulls in art!

Calacas and calaveras (skeletons and skulls) appear everywhere, in candied sweets, as parade masks, and as dolls.

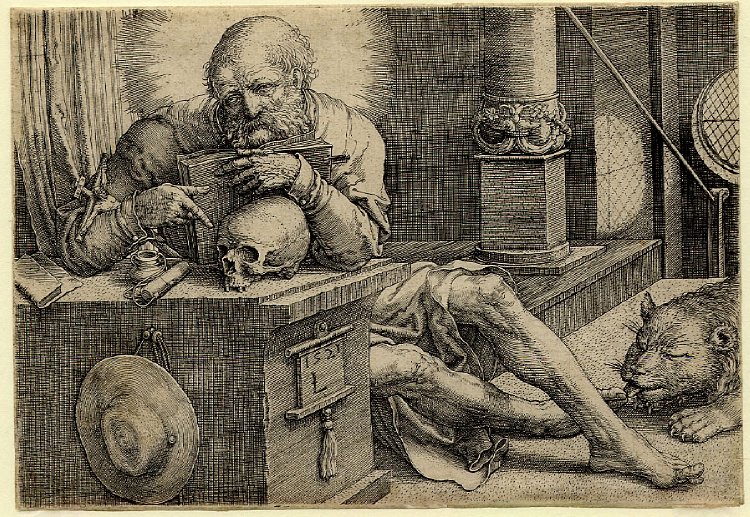

Skulls are popular in the art of many cultures, and it made me wonder about artists’ fascination with them. They have always appeared in art. Lucas van Leyden’s St Jerome muses over a skull in his study in 1521, referencing Albrecht Dürer‘s St Jerome of 1514.

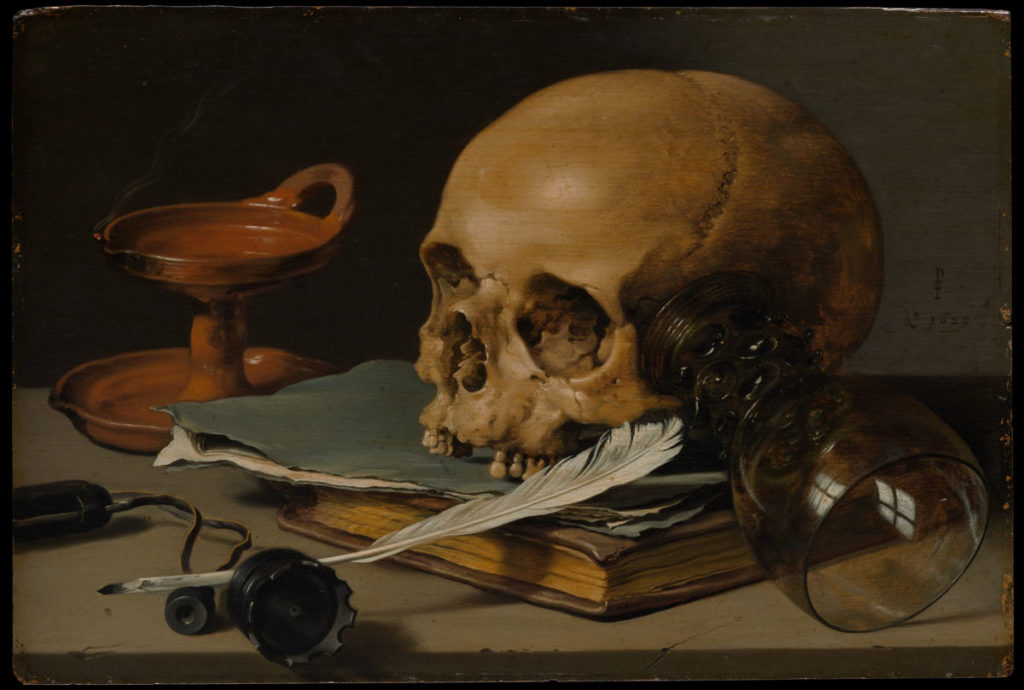

Pieter Claesz used a skull as the focal point in his Still Life in 1628.

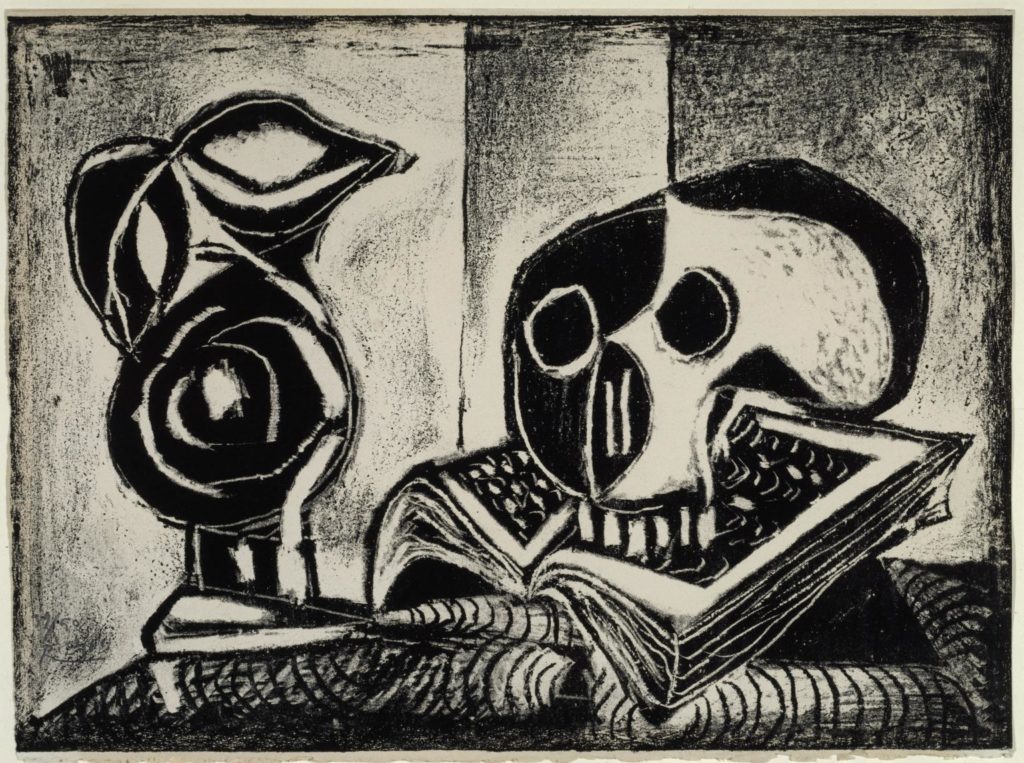

Pablo did a classic Picasso on his 1946 Black Jug and Skull.

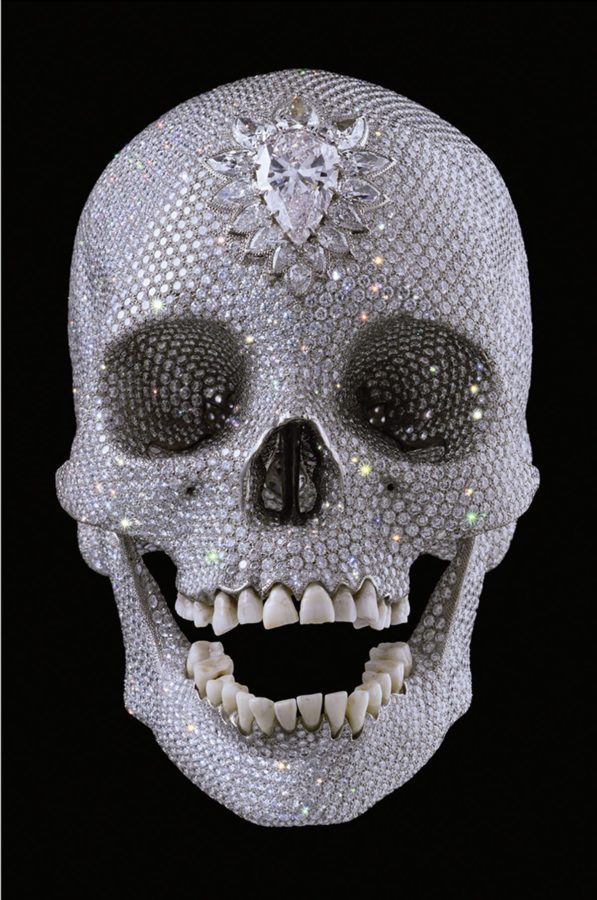

Of course, more recently, we saw the rather crass diamond encrusted 18th-century skull by master capitalist Damien Hirst, For The Love of God. It was acquired by an investment group for something between 50 and 100 million dollars (or so Hirst claims). Further controversy followed when he exhibited For Heaven’s Sake in 2008, the tiny skull of a 2-week-old baby, which he described as quite “bling.”

I remember a fascinating exhibition in 2017 called Ark. It was a public/private partnership held inside Chester Cathedral in England. Originally a Benedictine Monastery, this sumptuous architectural gem temporarily housed pieces by Elisabeth Frink, Barbara Hepworth, Sarah Lucas, Eduardo Paolozzi, and the aforementioned Damien Hirst. But for me, the most startling and mesmerizing exhibit was a series of four skulls by Steven Gregory.

Born in 1952 in Johannesburg, South Africa, Gregory studied at St Martins College in London and his early career was as a stone mason. His work combines a variety of materials, including human remains, semi-precious stones, bronze, and electronic parts.

He is known to sculpt with a “mischievous eye” and his work explores the human condition, celebrating life but not shying away from the idea of mortality and death.

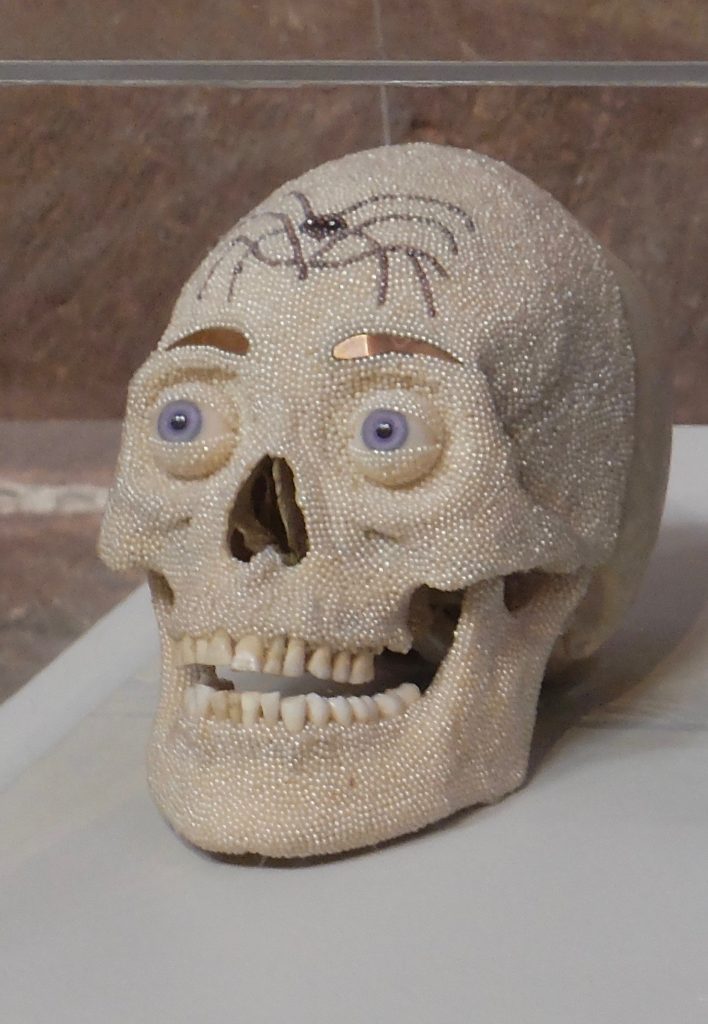

Housed in a glass case, in a row of four, Gregory’s art skulls seemed both humorous and profound. He says:

I have always felt bones were less morbid and more beautiful, so to decorate them is to commemorate them. Death is a part of life, and must be respected and celebrated.

This is the darkest of Gregory’s skulls, completely encased in a Russian jet with scarlet eyes. Gregory says that this piece forces the viewer to confront the notion that art only exists because death exists.

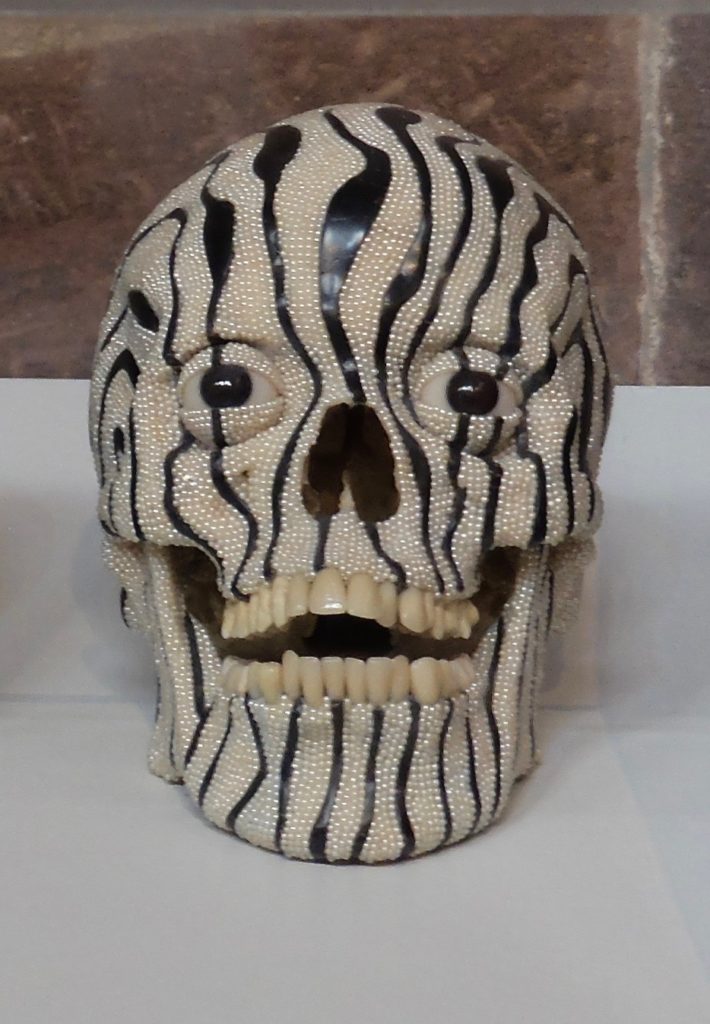

Gregory describes this striped skull encrusted with Russian jet, pearls, and diamonds as –

A flashy character who is not one to be trusted.

This pearl and gold skull takes its title from a Bible verse (Matthew 7:6):

Do not give what is holy to the dogs; nor cast your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn and tear you to pieces.

This skull flaunts its riches on the face, for all to see.

There is a clear reference back to Mexican culture in this skull, which shows the bold symmetrical patterns of Mexican wrestling masks. The inference seems to be, don’t we all wear a mask? The question is, how much do we flaunt it?

But why do these artifacts seem so different from the Hirst skull? Perhaps it is about intention. Gregory has been working on his art with skulls since 2001. He seems to honor them as precious artifacts and allows them to engage with the viewer. In 2002, Hirst purchased an embellished skull from Gregory. Was this the trigger for his own infamous 2007 skull? Gregory has been asked about the comparison with Hirst. He says:

My skulls and his are very different objects. I put eyes in mine – so the skull looks back; you interact with them. Damien’s is very different: with the diamonds, there is so much glare coming off, it’s as if you can’t quite get your eyes to focus on the surface.

However, when asked directly by The Guardian if Hirst owed him a debt of inspiration, he showed the reporter a postcard of 7,000-year-old decorated skulls. He said:

What I am doing is no different from what has been done in the past.

It appears that, despite social taboos, our fascination with bones and skulls is here to stay.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!