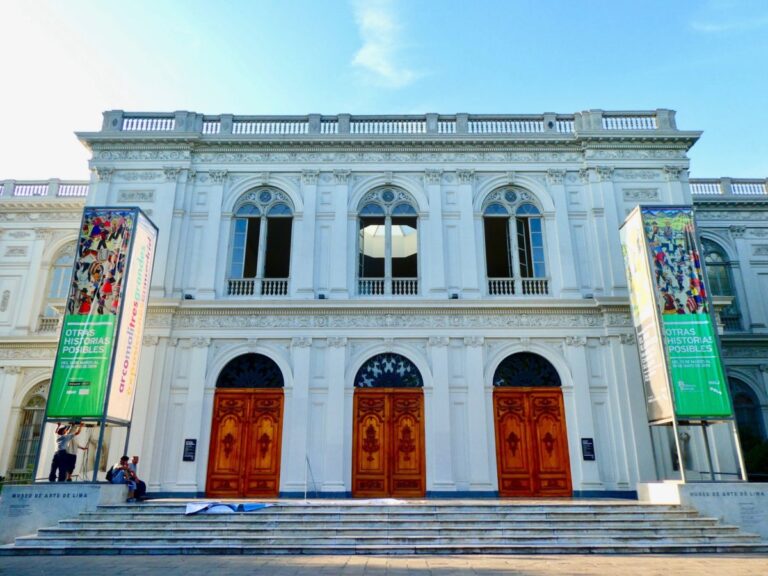

Welcome to the largest art museum in Peru: The Museo de Arte de Lima, aptly named MALI. It was opened in 1961 and presents around 1,200 works, arranged into four eras: Pre-columbian, Colonial, Republican and Modern/Contemporary. This chronological approach helped me to understand the history and evolution of art in South America, so I’ll use the same structure here with the aid of a few of the most relevant artworks exhibited in MALI.

1. Pre-columbian (1000 B.C. – 1532 A.D.)

It’s often hard to draw a line between what is art and what is craftsmanship. Proud of its pre-colonial civilizations, Peru considers the exquisite works that they have left us as artworks. Indeed, many of the most refined pieces, like the two I present here from MALI, were unique pieces made for ceremonial rituals or as offerings to the gods or to the lord.

Cupisnique culture (1500 – 500 B.C.): The Contortionist of Puémape

This peculiar bottle (yes, this is a bottle!) demonstrates the fantastic ceramic skills of the peoples from the northern coast of Peru. Because they had no writing system, most of what we know about them comes from all these jars and plates: their beliefs, traditions and everyday customs. Here, though, the meaning of the contortionist is unclear: Is he a victim of a disease, has he taken a ceremonial substance or does he symbolise the snake, a sacred animal? This bottle was found in Puémape in the tomb of an important person, as an offering and a sign of devotion.

Cajamarca (400-600 A.D): Tripod plate

This plate is from the Cajamarca, a civilization from a later time. It is perfectly shaped, with the use of two different natural pigments. The spiral (or wave) was a very common pattern in many native civilizations throughout South America, even when they didn’t have contact with each other. It represents the cycle of life and death, which are always intertwined. Most of these peoples believed in an afterlife in a parallel world. That is why all the tombs that were discovered contained jewels and objects of everyday life.

Other patterns commonly used, both on ceramics and textiles, were steps, fish, sacred animals and anthropomorphic figures.

Read more: Our practical guide to visit Lima

2. Colonial (1532 – 1821)

The paintings made during the early colonial period were by European artists, mainly Spaniards or Italians. Later, the descendants of the colonizers (read: white, rarely mixed race) were trained in full European style, reproducing the same features: white skin, European landscapes and buildings. The hype at that time was, of course, Christian topics.

Cusco School: Trifacial Trinity, ca. 1750 – 1770

Here is an interesting example of how distance can alter the teachings of the religion. If we are told that the Trinity is at the same time 3 and 1, why not draw it as 1 person with 3 faces? Well, the Catholic Church was not of the same opinion (I wonder why): They had all these paintings redone to show only one face. This trifacial trinity was a speciality of the Cusco School of art, recognisable by its lack of perspective, its realistic faces, and its unrefined clothes and backgrounds.

Cusco School: Lord of the Earthquakes, ca. 1740 – 1760

This gentleman is the Lord of the Earthquakes, the patron of Cusco. It is said that an effigy of Jesus kept in that town helped stop an earthquake in 1650.

Look at how dark and gory he looks. When the Catholic Church lost ground to Protestantism during the Reformation, their response, the Counter-Reformation, was to scare their followers back in line with threats of hell and a vivid imagery of the Passion. Many artists from the Spanish colonies therefore made religious works that are dramatic, showing tears, blood, and a dark background common to the Spanish Baroque style.

3. Republican (1821 – 1940)

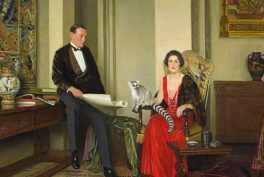

The first goal of a young Republic is to define and assert its own identity. This objective concentrates all fields of society, especially the arts. After independence was achieved, national artists consequently broke away from the colonial style and its religious works. They soon started painting portraits of the new bourgeoisie and representations of their true roots and identity.

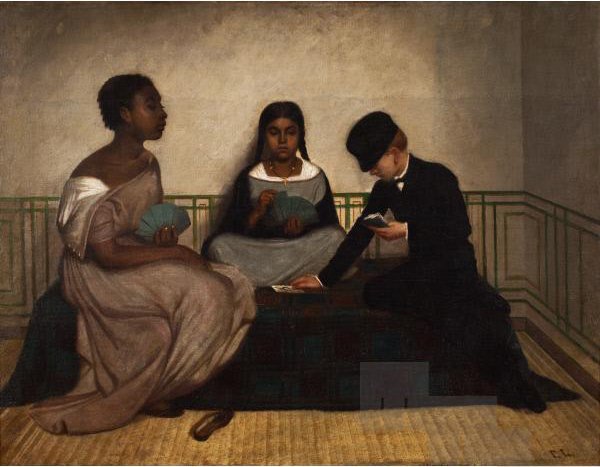

Francisco Laso (Peru, 1823-1869): The 3 Races, 1859

This is an obvious example of the new identity that the nation of Peru was going for. After 300 years of discrimination and slavery under colonial rule, the three “races” living in South America (the Indigenous, daughter of the natives; the White, son of the colonizers; and the Black, daughter of the African slaves) meet to share a symbolic moment of idleness.

Francisco Laso stayed three times in Europe, where he learnt the use of chiaroscuro and of neutral tones, which became his trademark. At the same time, the Old World appreciated his art for its representations of the indigenous. Back in Peru, he became an important politician.

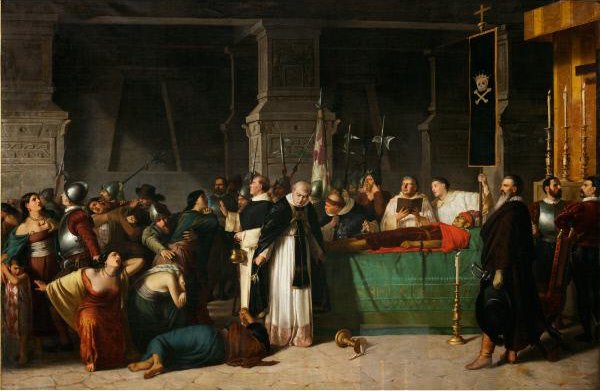

Luis Montero (Peru, 1826 – 1869): The Funerals of Atahualpa, 1867

Like most South American artists of that time, Luis Montero was trained in Europe and this magnificent work (420 x 600 cm and weighing 200kg!) was in fact created in Italy. It is an important piece in the history of South American art and it holds a central place in the museum. It is a great example of “Indigenismo“, which we’ll get to soon.

The historical painting aims to show the superiority of the indigenous (here: Inca) origins over the Spanish past. Atahualpa, the last Inca ruler, was killed by conquistadors such as Francisco Pizarro (the third figure from the right). Observe the mixture of indigenous imagery (the face and dress of the Inca, the windows, the symbols on the columns) and European influence (the structure of the painting, the classicist columns, the European faces of the women).

Read more: Inca architecture around Cusco, Peru

4. Modern & Contemporary (since around 1940)

In 1940, several South American countries officially adopted the line of “Indigenismo“: the recognition of the cultures and rights of indigenous peoples and their full integration within society. Artists were particularly keen on it, even though many of them still looked to Europe for training and influence.

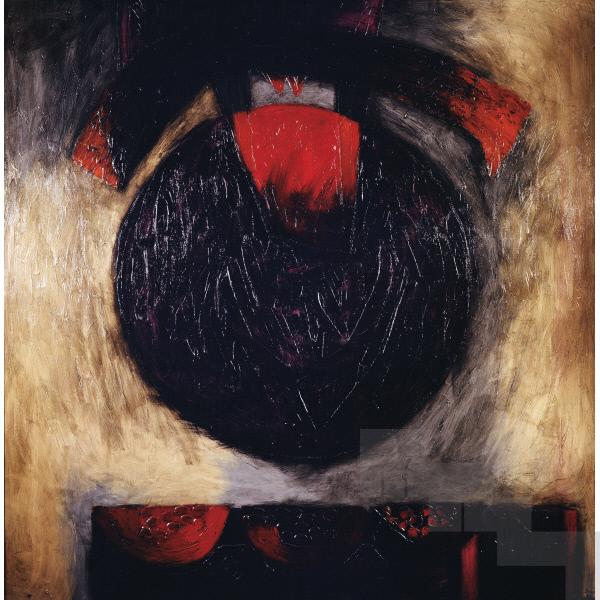

Fernando de Szyszlo (Peru, 1925 – 2017): Puka Wamani, 1968

This painting by Fernando de Szyszlo, a Peruvian artist of Polish origins, has a title in Quechua. Quechua was the language of the Incas and is still spoken today by around 9 million people, mainly in Peru’s countryside. Both the title and the shape clearly link to Peru’s indigenous peoples: The circle is obviously a divine figure, and the presence of claws and fangs refer to animals that were sacred for the natives. Also, the use of both dark and bright tones – darkness and light – represents the duality that was so important for several pre-Inca civilisations. The point is to give to abstraction, which is usually an international language, a local interpretation.

De Szyszlo lived for several years in France, where he became acquainted with Octavio Paz, André Breton and abstract art, which he widely promoted upon his return to Peru in 1951.

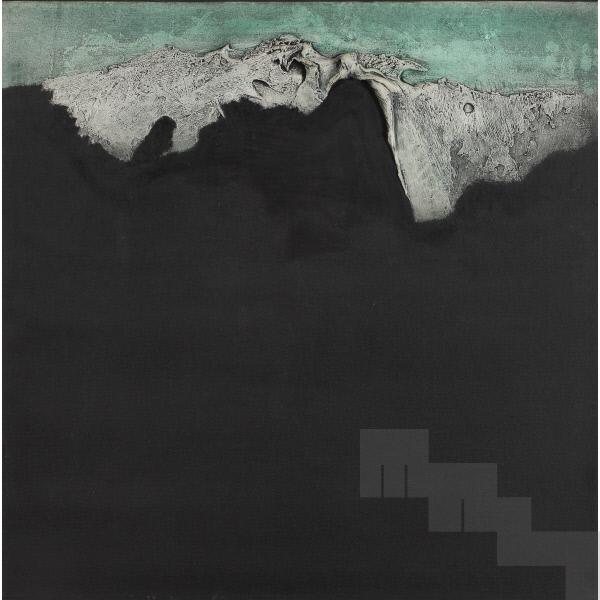

Jorge Eduardo Eielson (Peru, 1924 – 2006): Infinite Landscape of the Coast of Peru, 1961

This painting by Jorge Eduardo Eielson is part of a collection of six pieces. The artist’s intention was to tell the story of Peru’s fishermen, using words, sand, hair, animal bones, fabric, and so on. Over time, the idea evolved and Eielson decided to focus on space. Hence the large black area covering three fourths of the square canvas. In order to link it to the fishermen’s story, he mixed sand with the paint. He also used fabric to make the white-grey part. I find that this painting can be seen both as a coastline seen from above, or as a mountain with a greenish sky.

The artist generally employed earth, small stones and animal bones and feces. His goal was to include physical and mineral aspects of the landscape he was representing. Jorge Eielson was also a sculptor, a photographer, a poet and a playwright.

Read more: Beautiful jewellery found in northern Peru

Susana Torres (Peru, 1969- ): Self-Portrait, 2006

In conclusion, look at how this modern sculpture by Susana Torres is a clear return to Peruvian roots!

And with this we close the loop, because art is a perpetual looking back and moving forward. If you’re in Lima, I really recommend spending some time in MALI. A guide can also take you on a tour to help you understand the evolution.

Address: Parque de la Exposición, Paseo Colon 125, Cercado de Lima, Peru

Entry: 30 soles for foreigners (15 for Peruvians)