Spellbound by Marcel

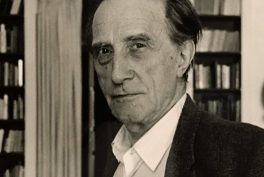

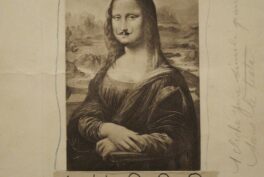

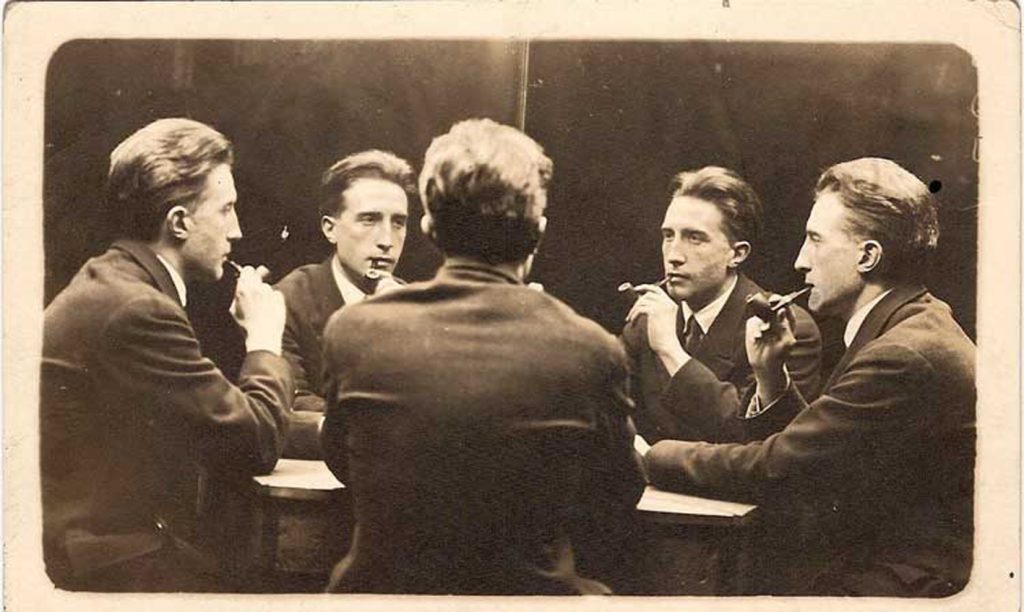

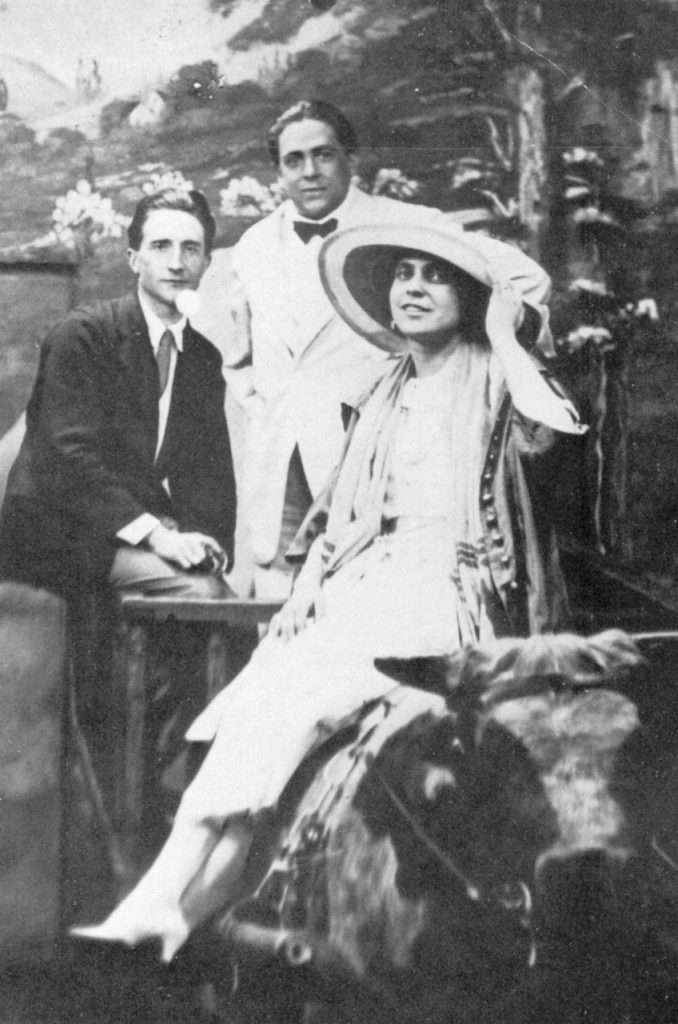

Spellbound by Marcel follows the antics of Marcel Duchamp and the circle of avant-garde thinkers he befriended while waiting out World War I in New York City. Ostensibly, it’s about the people who fell in love with Duchamp in one way or another, but that’s really more of a jumping-off point than a real focus. In truth, the book isn’t really about Duchamp, since the narrative often takes extensive detours away from him. It’s even less about his art; if anything, the author consistently de-emphasizes art’s role in Duchamp’s life and only glosses over his later artistic fame. Instead, the book is really about the many wild love affairs that took place amongst Duchamp’s New York friends.

A Little Light Reading

Spellbound by Marcel makes for some enjoyable reading. The revolving door of affairs, breakups, betrayals, and wild avant-garde stunts is quite juicy, making this book the perfect thing to read over spring break. It’s also impressively researched, judging by the profusion of primary and secondary sources referenced at the bottom of each page. Braden speaks with the authority that comes from intimate familiarity with the key players’ own words about their lives. Despite this, the tone is quite readable – more conversational than scholarly. All those sources never burden the narrative.

Entertaining and well-supported though it may be, I’m not sure I really gained much from reading Spellbound by Marcel. I didn’t learn anything new or gain any meaningful insight into Duchamp’s life, personality, or art. As mentioned before, neither gets as much of the focus as the book’s title and blurb would suggest. In fact, a large part of the narrative dwells on a relationship only tangential to Duchamp – the brief love affair between his friends, the American artist and writer Beatrice Wood (1893-1998), and the French writer/opportunist/sex addict Henri-Pierre Roché (1879-1959).

In fact, Duchamp becomes rather scarce for much of part two, by far the longest section of the book. He does reappear after that, though, in time to have some questionable adventures in matrimony in the years following World War One. Although the book follows Duchamp and some of his friends through to the ends of their lives, this later material receives a rather summary treatment. This is unfortunate because those are the years in which several of them – Wood in particular – actually achieved the greatest artistic success.

It’s All Fun and Games… or Is It?

Duchamp ran with an uninhibited, free-thinking set, where everybody supposedly engaged in free love without emotional consequences. However, one gets the impression that in actuality, it only worked that way for a few people, mostly the men. Duchamp and particularly Roché looked pretty callous, at best, in their treatment of the myriad women in their lives.

To be fair, they do come across as eager to respect and collaborate with women professionally. They also seem like they were pretty decent friends to the women they weren’t sleeping with, and I didn’t get the sense that Marcel or any of his friends was at all abusive. However, almost all the men in the story felt quite comfortable double (and even triple) timing their girlfriends, stringing one along while gallivanting with another, and just expecting everyone to be okay with it.

Without openly judging them, Brandon sets out their behavior and lets it speak for itself. But thanks to her deep dive into the aforementioned first-person sources, we get to hear their own words about these relationships. This perspective does them no favors, at least in the selections the author chose to share with us. Brandon also doesn’t seem inclined to judge any of the group’s other unconventional behavior, either for good or for ill. Instead, she gives readers the refreshing opportunity to form their own opinions about these often-perplexing people.

Women Who Deserve Better

I have issues with how Duchamp and his friends sometimes treated women, but I don’t like how Brandon treats female characters, either. On multiple occasions, I found her prose to come across as downright dismissive towards some of the women in the narrative, particularly those who did not participate in the avant-garde sexcapades.

Most egregiously, Brandon repeatedly characterizes some of Duchamp’s friends, specifically the Stettheimer sisters and Katherine Dreier, as rich, middle-aged hangers-on. She literally classifies them under the heading “Marcel’s Wealth, Middle-Aged Lady Friends” in the opening list of characters, as though they weren’t important modernist artists and thinkers in their own rights. Their middle-aged status crops up almost every time these women appear, usually alongside some comment about Dreier’s broad girth and suggestion that these ladies were somehow unworthy of Marcel’s time. This is just disappointing, especially coming from a 21st-century female author. Both art collector Dreier and the much-celebrated Stettheimers deserve much better.

I genuinely enjoyed reading Spellbound by Marcel, albeit in a superficial sort of way. It’s a fun enough read if you like avant-garde antics and Gossip Girl-worthy tales of complicated romantic entanglements. But if you’re craving interesting content about Marcel Duchamp and his work, I would suggest looking elsewhere.

Spellbound by Marcel: Duchamp, Love, and Art by Ruth Brandon was released on March 1, 2022, by Pegasus Books.