Lotus Temple and the Bahá’í Faith

The Lotus Temple is renowned for its distinctive lotus shape. A prominent Bahá’í House of Worship in New Delhi, the temple embodies...

Maya M. Tola 27 January 2025

St. Peter’s Basilica is one of the most iconic buildings in Western culture. But, the facade we see today is the culmination of centuries of changes, decisions, and work. Going down the layers of history we find that great things can come from small beginnings.

Rome is not called “The Eternal City” for nothing. It seems like everywhere you let your fancy go, the excitement of the ages is always there. It connects you to the past—where so many others walked before you—and to the future—where you yourself will go, leaving something to those who come after you. Archaeology is one tool that helps us connect all these intersecting points between the past, present, and future. One of the world’s most famous examples of this intersection is the history of St. Peter’s Basilica, in the Vatican.

The facade of St. Peter’s is well-known throughout the Western world and beyond. Whether visiting the Vatican on pilgrimage as a believer, or watching the election of a new Pope on TV, St. Peter’s sheer size and imposing architecture can easily take one’s breath away. Just like everything else in Rome, St. Peter’s reflects the hopes, tastes, and humanity of all the people involved in its construction throughout the ages. The story behind this iconic building is as interesting as it is enlightening. It includes many side stories that, eventually, converge in the church we know today.

Let’s begin at the beginning: for St. Peter’s Basilica, it all began with an act of cruelty.

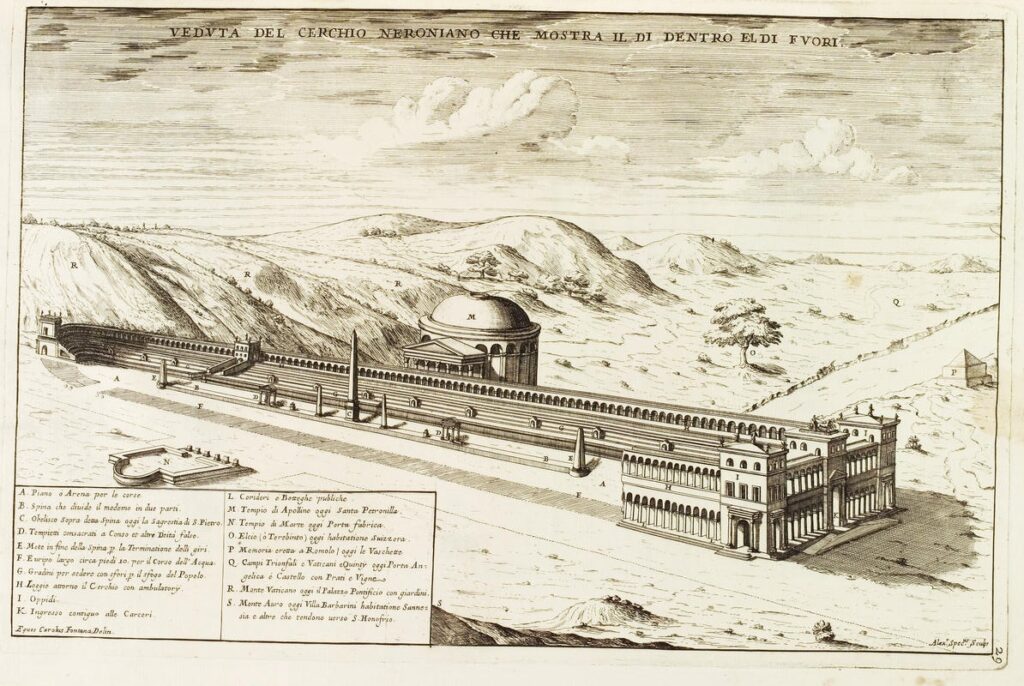

Carlo Fontana, Circus of Nero, from Il Tempio Vaticano e la sua origine, Rome, 1694. Roger Pearse.

The name of Nero conjures up images of savagery and madness. He is most famous for allegedly setting Rome on fire, and for his persecution of Christians. Both these claims come into play in the history of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Around 64 C.E., Rome burned in a fire that lasted 6 days. When the fire had run its course, 70% of the city lay in ruins. Historians like Suetonius and Cassius Dio believed that Nero had been behind it all, hoping to clear the area for a building project he wished to call Neropolis. The displaced citizens also blamed Nero for the fire, so he found a convenient scapegoat in the relatively unknown sect of Christianity.

Portrait of Nero, 54–68 CE, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy.

Nero blamed the fire on the refusal of the Christians to worship the Roman gods. Thus began a terrible chapter in history- where people were persecuted for their beliefs and killed for entertainment. It was convenient for Nero to host these executions at the Circus, since most of the victims of the fire had been relocated in that vicinity. He hoped to appease them by avenging their losses with the death of Christians.

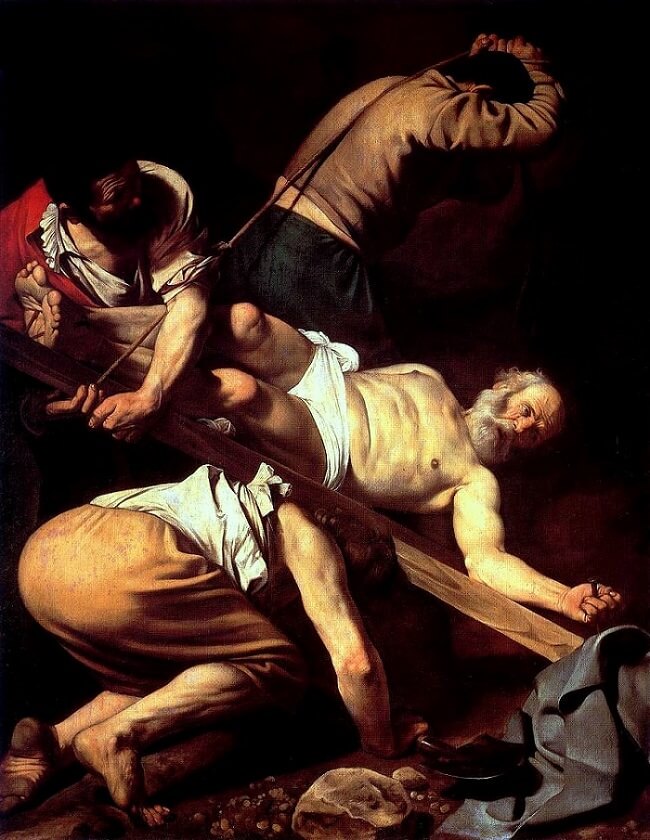

Caravaggio, The Crucifixion of St. Peter, 1601, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy.

It was within this setting that the apostle Peter was martyred. Christians believed that Peter had received the authority to preside over the Church from Jesus himself. Tradition holds that Peter asked his executioners to crucify him upside down, saying he was not worthy to die in the same way as his Master had.

After Peter’s death, his friends and followers took his body, placing it in a nearby Necropolis.

The Tomb of the Caetenii at the Vatican Necropolis. Photograph by Nat Farbman. The LIFE Picture Collection.

The Vatican Necropolis conveniently stood near Nero’s Circus. It was forbidden to bury the dead within city walls during Imperial times, so many cemeteries and burial grounds sprang along the roads outside city limits. One of the differences between a cemetery and a necropolis is that cemeteries are usually for underground burial, while ancient necropolises are almost like dwellings for the dead. Here, the most common burial method was a sarcophagus, though the dead could also be buried underground, or cremated and their ashes placed in urns within niches. The Romans had feast days where entire families visited their dead and had parties at the Necropolis.

The Tomb of the Egizio at the Vatican Necropolis. Photograph by Nat Farbman. The LIFE Picture Collection.

Christians venerated the bodies of saints and, particularly, the bodies of martyrs. Because Peter was a very important martyr, it makes sense that his followers would have wanted to preserve his body without calling a lot of attention to it due to increased persecution. A very logical and convenient place was the Vatican Necropolis, adjacent to the Circus, where Peter’s body would have gone unnoticed with all the others already resting there.

The Christians would only have been able to quickly afford a poor man’s grave, essentially a hole in the ground, where they would have placed the body much as we would today. Then, they would have covered it with terracotta tiles, forming a gable.

Reconstruction of The Trophy of Gaius. The Lonely Pilgrim.

As time went on, more and more Christians came to worship at the site of Peter’s tomb. Around the year 150 CE, members of the Church decided to build a better marker to assist the pilgrims. This monument became known as The Trophy of Gaius.

The Trophy of Gaius was intentionally built to resemble a pagan monument, a shrine known during Roman times as aedicula. Aediculae were household shrines dedicated to the Lares, the deities protecting the house and family. The aediculae looked like a niche, surrounded by two columns and topped by a pediment. In the case of The Trophy of Gaius, the structure was large enough to accommodate a platform for a man to climb and preach mass while, at the same time, having a view of the road. The area surrounding the platform was used to perform baptisms.

The marker’s name references Gaius, who was a Christian living in Rome around the year 200 CE. Gaius was famous for having exchanged letters with a man called Proclus, where he argued the importance of Rome as a center of Christianity. He argued that after Christ’s death, all the apostles had dispersed. But, Rome had something special.

I can show you the trophies of the apostles. If, in fact, you go out towards the Vatican or along Via Ostia, you will find the trophies of those who founded this church.

– Gaius, Ecclesiastical History, II, 25, 6-7

Peter Paul Rubens, The Emblem of Christ Appearing to Constantine, 1622, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

In the year 312 C.E., Constantine defeated his rival Maxentius at the battle of the Milvian Bridge. By the end of 324 CE, he emerged as the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Constantine ascribed his victory to the intervention of the Christian God. Tradition holds that Constantine had received a vision of the Christian sign Chi Rho during one of his campaigns, and heard a voice that told him, “In this sign, conquer.”

To show his devotion, Constantine began the construction of a church in Rome, the Basilica Constantiniana, now San Giovanni in Laterano. However, when he noticed that believers continued to worship at the site of Peter’s tomb, he decided to begin construction of a new building on the very spot where The Trophy of Gaius stood.

Representation of Old St. Peter’s Basilica. ChurchPOP.

The construction of what is now known as Old St. Peter’s Basilica began between 318-322 CE, and lasted for 40 years. Old St. Peter’s had a wide central nave, with two smaller aisles on either side. It was over 350 feet long (ca. 107 m), with the addition of a transept, giving it the shape of a Latin cross, and a gabled roof that stood 100 feet (ca. 30 m) at its center. It could accommodate 3,000-4,000 worshipers.

The altar of Old St. Peter’s used Solomonic columns that, according to tradition, Constantine had brought from the Temple of Solomon itself. The interior of the church was lavishly decorated with mosaics and frescoes, most notably by Giotto. Some of these can still be observed at other churches and museums, such as a fragment of the Epiphany mosaic at Santa Maria in Cosmedin, or the standing Madonna on a side altar in the basilica of San Marco in Florence.

Constantine’s Old St. Peter’s Basilica remained in use from the 4th century until the 16th.

After Giotto, Navicella Mosaic 1305–1313, 1628. Web Gallery of Art.

By the end of the 15th century, the old basilica had fallen into disrepair, particularly during the period of the Avignon Papacy. It seems that the first Pope to consider rebuilding Old St. Peter’s was Nicholas V. He commissioned repairs from Leone Battista Alberti and Bernardo Rossellino, and, at the same time, had Rossellino develop a design for an entirely new church in the shape of a domed Latin cross. However, when Nicholas V died, not much had been done in the way of construction.

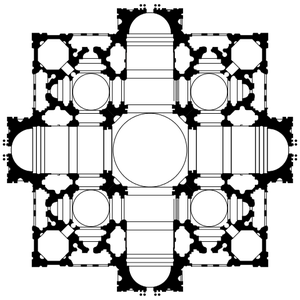

It was Pope Julius II who envisioned a more radical plan for the new St. Peter’s, which called for a complete redesign and demolition of the ancient basilica. To that end, he promoted a competition, with many of the designs still housed at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The author of the winning design was Donato Bramante. His plan was to create a church in the form of a Greek cross, with a dome inspired by the dome at the Pantheon and Brunelleschi’s dome at Santa Maria del Fiore, in Florence.

Donato Bramante, Plan for St. Peter’s Basilica, 1506. SmartHistory.

The foundation stone for the new basilica was laid in 1506 and, for the next 120 years, a succession of Popes and architects worked on the project. Figures such as Fra Giocondo, Raphael, Baldassare Peruzzi, and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger all were involved at one point or another. Michelangelo came on board in 1547, becoming the principal designer of a large part of the building—mainly the chancel (the space about the altar) with its dome. He truly brought the construction to a point where it could be carried through, consolidating the many changes the project had undergone throughout the years, and bringing them into cohesion using Bramante’s original plan as a guide. The dome was completed in 1590 by Giacomo Della Porta and Domenico Fontana.

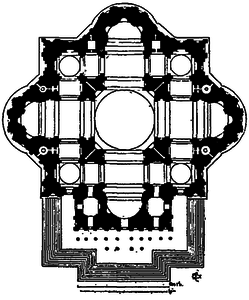

Michelangelo, Plan for St. Peter’s Basilica, 1547. SmartHistory.

Carlo Maderno added a nave in the early 1600s. One of the reasons for the addition was the climate during the Counter-Reformation, which associated a Greek Cross floor plan with paganism, while the Latin Cross was the true symbol of Christianity. Another reason was the necessity to demolish all vestiges of Old St. Peter’s to proceed with the construction, including its associated chapels, vestries, sacristies, and even tombs—all hallowed ground. The committee in charge thought that, if they extended Michelangelo’s building with a nave, they would encompass the whole space and preserve the sanctity of the old church.

The building of this nave began on 1607, and proceeded at a fast pace, with 700 laborers working at the site. The nave was first used on Palm Sunday, 1615.

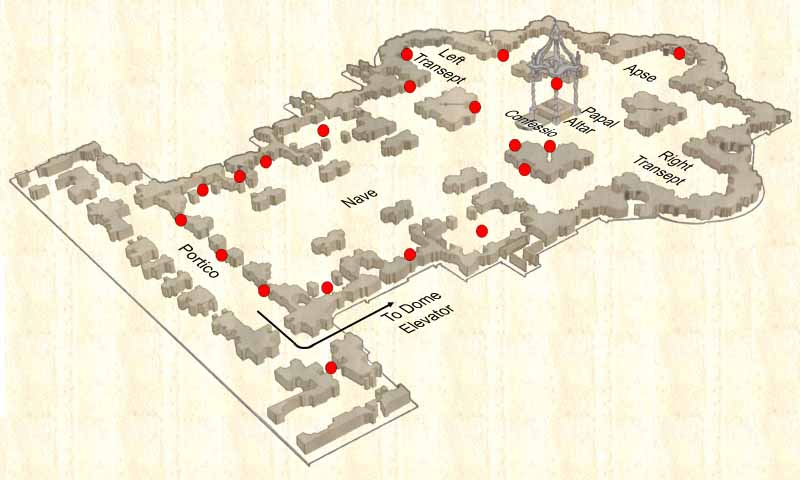

Current Floor Plan of St. Peter’s Basilica. St. Peter’s Basilica.

In 1626, under the patronage of Pope Urban VIII, Gian Lorenzo Bernini began work on the embellishments of the Basilica, and he continued to do so for the next 50 years.

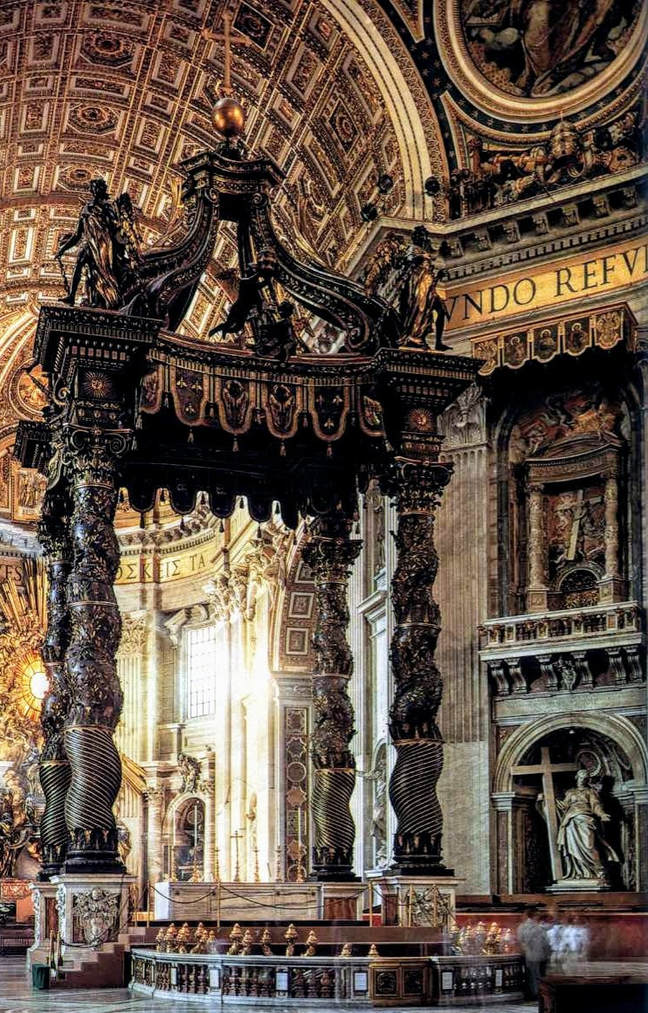

Bernini worked on many projects for St. Peter’s Basilica. One of the most notable was his design of the Baldacchino, which is the bronze pavilion that stands beneath the dome and above the altar. This design is based on the ciborium, or freestanding canopies in the sanctuary of a church, whose purpose is to create a holy space surrounding the table on which the sacrament is laid for the Eucharist. Bernini was also inspired by the canopy that goes above the head of the Pope in processions and, particularly, by the eight ancient columns of the altar at Old St. Peter’s Basilica—the ones believed to have been brought by Constantine from the Temple of Solomon.

The Baldacchino is 94.3 feet (ca. 29 m) tall and its visual effect is to link the dome to the congregation, as well as providing a frame for the Cathedra Petri, the chair of Peter which rests in the apse behind it. This chair links the authority of St. Peter, the first apostle, to that of the Church today. Most importantly, the Baldacchino is placed directly above the original site of Peter’s tomb, where the Trophy of Gaius used to be.

Bernini also created balconies and niches to display the four most precious relics of the Basilica:

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Baldacchino, 1624–1635, Vatican. Pictures from Italy.

View of St. Peter’s Square from the Dome of St. Peter’s Basilica. Author’s Photograph.

Bernini also worked on St. Peter’s Square between 1656-1667. The square’s centerpiece is an 83 feet (ca. 25 m) tall Egyptian obelisk, “The Witness,” that had once stood to the side of the Basilica, in what had been the Circus of Nero. If it had been in the Circus, it would have witnessed Peter’s martyrdom. In 1586, Domenico Fontana relocated it to better align with Maderno’s facade, and Bernini used it to heighten the symbolism of the space.

Pope Alexander VII commissioned the famous Colonnade in 1656. Bernini designed the square in the form of a trapezoid plaza nearest the church, then an elliptical circus that reaches out in two arcs, symbolic of the arms of the Catholic Church reaching out to embrace its followers.

When construction began with Bramante in the 1500s, the building was meant to be a freestanding temple, inspiring reverence and awe by standing in isolation. Bernini’s Baroque conception of the space integrated the architecture to its environment in a symbolic manner, turning St. Peter’s Basilica into one of the greatest religious sites in Christendom.

Vie of St. Peter’s Basilica from St. Peter’s Square, Vatican. Author’s Photograph.

St. Peter’s Basilica stands as the symbol of the Catholic Church before the world. At present, there are over 100 tombs within the Basilica, including 91 popes, an emperor, a composer, and even members of the British Royal family. The historical value of the artwork- in the form of mosaics, statues, bronzes, carvings, gold leaf and artifacts- is incalculable. From an archeological perspective, the preservation of structures that date to the days of the Roman Empire beneath the church, as well as all the subsequent modifications, is enough to turn St. Peter’s into a living, historical document.

But, even more than all of this, St. Peter’s Basilica provides an opportunity for reflection and contemplation, which will be different for each and every one of its visitors. The reverence and devotion and, yes, sometimes even ambition, of the many people involved in its construction still inspire awe and wonder, even today. After a visit to St. Peter’s, one will come out transformed. Perhaps, Peter himself said it best, when he said:

For we cannot but speak the things which we have seen and heard.

– Peter, the Apostle (Acts 4:20).

The story of the construction of St. Peter’s and the discovery of Peter’s own tomb is fascinating in every regard. Here are a couple of other sources which might be of interest to expand on the information presented in this article:

The Vatican Necropolis (Scavi) Presentation, by St. Leo the Great Catholic Church

This is a wonderful presentation that takes the viewer as close as possible to St. Peter’s tomb. This is a small tour that can be accessed at the Vatican, where visitors descend to the site of the ancient Roman Necropolis. Pictures are not allowed, so this video is a real treat, presented by Fr. Logue, who used to give the tour during his time in Rome.

Vaticano—St. Peter’s Basilica, by EWTN

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!