Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

Subway by Lily Furedi is a masterpiece of New Deal art that expresses the excitement of modern transportation. It is populated with commuting workers heading towards a common direction. It is also filled with hidden stories and stolen glances.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

The United States and most of the developed world were experiencing the Great Depression during the 1930s. It was a time of high unemployment, widespread poverty, and deep hopelessness for many people. United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated the New Deal in 1933 to organize public work projects, thereby attempting to improve the financial and social situations of the country. In 1934 thousands of American artists were commissioned to create artwork under the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) to be placed in public and government spaces. Lily Furedi received such a commission and created her Subway for the government of New York City. Subway is therefore a masterpiece of womanly creativity and New Deal Art.

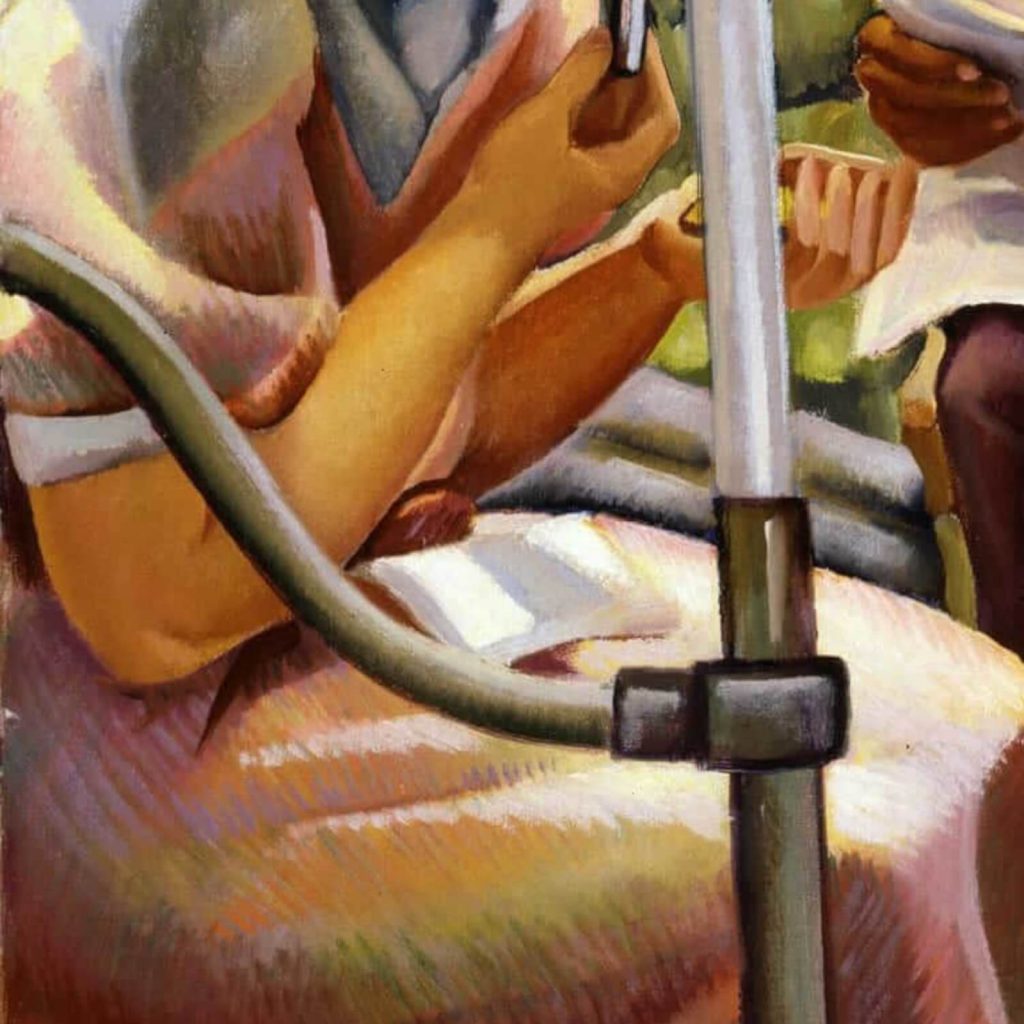

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Lily Furedi painted Subway in 1934 as an oil on canvas. It measures 123 centimeters wide and 99 centimeters high (or 48 inches wide and 39 inches high). The image captures the populated interior of a New York City subway car from the low perspective of a sitting passenger. The viewer joins the riders on their daily morning commute.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Taking the subway is not like taking a car to work. The subway is not a private space, therefore social rules and customs exist that conscientious riders follow. There is an unwritten rule that riders do not look or stare at each other. They keep their glances averted or occupied by some reading material. For example, in the center-left midground of Subway there is a man in a purple suit who is following such a motion. He holds a newspaper in his hands and the tilt of his hat indicates he is reading it in deep reflection.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

However, not all passengers dutifully contain their gaze. The woman sitting to the mentioned man’s left is secretly side-glancing upon his newspaper over his shoulder. She is breaking the unwritten code with clandestine enjoyment, implied by her smirking lips. A man in a white hat on the far-left midground also disturbs the social rule by staring at the neighboring woman in the far-left foreground, who is applying red lipstick. Is his look of mere curiosity or of desire? His eyes are hard to read through the dark shadow of his hat.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

On the far-right foreground are two women facing each other who appear to be in deep conversation. These two women know each other because there is an amiable look in the eyes of the woman facing the viewer. She widely smiles as she listens to the woman whose back is to the viewer. The two women’s heads lead forward together to shield outside listeners, while they exchange an enjoyable anecdote or discussion. The woes of the Great Depression are not upon their lips. They are speaking about something amusing or enjoyable, perhaps even a juicy bit of gossip heard in the city.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

In the center-right midground sits a violinist in a formal black suit. He is sleeping with a slight slouch forward as he holds his violin between his legs. He wears elegant evening attire frequently seen by musicians playing at nightclubs. Perhaps unlike the other morning commuters, he is not heading to work but returning from work? Perhaps he lacks the energy of the other commuters because this morning is not the beginning of a day shift but the end of his night shift? Lily Furedi would have understood and possibly sympathized with this possible nocturnal worker because Lily Furedi’s father, Samuel Furedi, was a cellist who often played in the evenings at various establishments.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Behind the violist in the far-right background is a pair of lovers. Their facial profiles lean together as they are about to kiss. The lovers take advantage of the unwritten social code as no one will stare at them while they quickly embrace. It is a secretive moment happening in a public space shielded by averted eyes. Love is seen by the viewer but unseen by the painting’s occupants. The viewer is now engaging in his or her own covert glance and is breaking the code. Doesn’t it feel indulgently delightful?

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Modern riders of the New York City subway system could easily agree that many subway cars are in terrible condition. Many subway cars have trash, graffiti, and dirt throughout the interiors. They are also frequently crowded with standing-only conditions. However, Lily Furedi does not depict a grim riding experience for her viewer. Her viewer is treated to a tidy, unmarked, and clean interior. It is spacious with almost everyone having a seat.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Is Furedi showing an idealistic experience? No, she is not. She is showing in realistic detail what a rider may have experienced in 1934 upon the Independent Subway System (ISS), which opened in 1932. Therefore, in 1934, the ISS was new and exciting. It had more seats than older lines and boasted ceiling fans for rider’s comfort during warmer months. It represented the modernity and progress promoted by New Deal legislation.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

The R1 subway car was manufactured and painted in a wide arrangement of colors that Lily Furedi beautifully captures on her canvas. She depicts the yellow wicker seating, the red rubber flooring, the olive paint walls, and the white enamel railings. Furedi’s R1 interior was realistic and relatable to her original 1934 audience, who potentially experienced the same space twice a day. It also captures the positivity felt by the public over the opening of a modern, convenient, and affordable transport line.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Lily Furedi’s Subway captures the daily life of working America. There is a sense of glamorous modernity as these viable workers head toward their destinations. There is a sense of American endurance despite the gloom of the looming Great Depression. It is New Deal. It is Women’s History. It is a masterpiece.

Lily Furedi, Subway, 1934, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!