Apollo and Daphne in 5 Artworks

From Ancient Rome to the Renaissance and Rococo, the timeless appeal of the Apollo and Daphne myth spans centuries of artistic expression. The myth...

Anna Ingram 30 January 2025

Throughout her inspiring life, Suzanne Valadon transitioned from an in-demand model to a successful artist. Along the way, she challenged societal and artistic traditions by living and working by her own rules. Her story was presented in 2021 show Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, PA, USA, which inspired this article.

Suzanne Valadon was born Marie-Clementine Valadon in the French town of Bessines-sur-Gartempe in 1865 to a single working-class mother. The two, along with Valadon’s half-sister, eventually settled in Montmartre. High on its hill, Montmartre had only recently become part of the city; its location offered affordable housing and jobs to the lower classes. Around them sprung up the cafes and concert halls for which the area would become known.

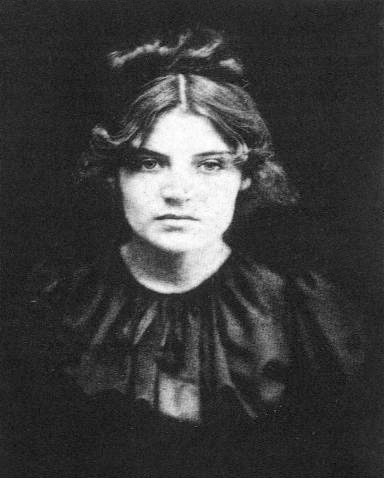

Photo of Suzanne Valadon, painter and model. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The young Valadon grew up in this artistic heart of Paris, which must have instilled in her a street-savvy. She worked various jobs: dressmaker, laundress (delivering laundry to neighbor Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec), and trapeze performer. Around the age of 15, Valadon began modeling for several artists including Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Toulouse-Lautrec nicknamed her “Suzanne” – a joke referring to “Susanna and the Elders,” the biblical story where a young woman is spied on and propositioned by older men.

You might be familiar with her without even realizing it. She was the model in Gustav Wertheimer’s The Kiss of the Siren, in Renoir’s Dance at Bougival, and in Puvis’ The Sacred Grove.

During this time, she created her own drawings that were noticed by Toulouse-Lautrec who encouraged Valadon’s talent and skill. Being of a lower class, she could not afford a formal education. This is why she used her time as a model to observe and learn from the artists as they worked. This was primarily the extent of her artistic training.

Her image was manipulated for the purpose of the artists and so she is not always recognizable in their works. There are, however, familiar traces that can be found: her hairstyle in Santiago Rusiñol’s Laughing Girl and her jawline in Toulouse-Lautrec’s The Hangover.

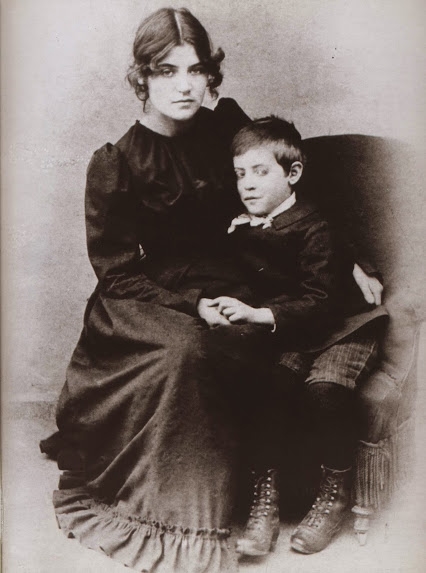

In 1883, Valadon gave birth to her only child, Maurice. Though her friend and sometime lover, Miguel Utrillo, gave the boy his last name, it is believed he did so to make the baby legitimate and to make life a little easier for everyone. Maurice Utrillo would serve as a model for his mother throughout his life.

Suzanne Valadon and Maurice Utrillo, c. 1890. Wikiwands.

Through Toulouse-Lautrec, Valadon met Edgar Degas. He took her under his wing, supported her, and encouraged her to try engraving. We see the trial and error, her signature is reversed on a few of the prints, as Valadon learns to navigate this tricky medium. In some of her drypoints we can see a young Utrillo alongside Valadon’s mother, Madeline, or drawings of a young girl taking a bath.

Suzanne Valadon, The Bath (Le bain), 1908, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI, USA.

At this point Valadon started to get noticed: her drawings began to sell, and her work was finally exhibited. She married wealthy businessman Paul Mousis in 1896 and, later, the family would settle in a quiet Parisian suburb. For the first time in her life, she did not have to worry about money. This enabled her to create what she wanted rather than what might have selling power. However, her son’s alcoholism and mental illness that was to plague him his entire life began to emerge. As a kind of therapy, and to help him cope, Valadon taught him to paint, setting him on his path as a successful cityscape artist.

In 1909, Utrillo introduced his 44-year-old mother to his 23-year-old friend, André Utter. It appears that Utter was just the rejuvenation that Valadon did not know she needed. Along with Utrillo and Madeline, the couple returned to Montmartre, moving into an apartment together. Valadon and Mousis divorced the following year.

It is perhaps unsurprising that after all this upheaval, her creative output evolved. Until then, her primary mediums were works on paper, but she now focused more on oil painting. She often painted works featuring those she was closest with.

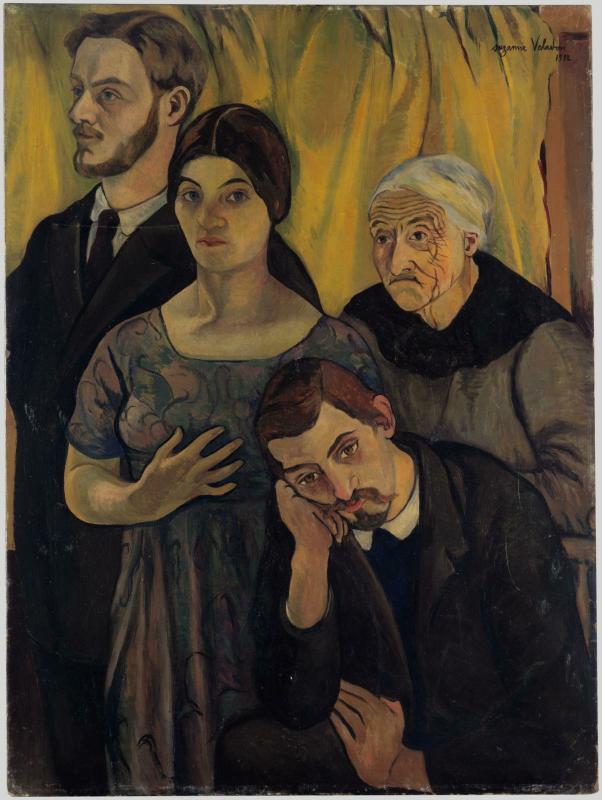

Suzanne Valadon, Family Portrait (Portrait de famille), 1912, Musée d’Orsay, on deposit at the Centre Pompidou-Musée National d’Art Moderne/CCI, Paris, France.

In Family Portrait, Valadon shows their unique family dynamic. Utrillo in the foreground looks resigned and dejected. Does this pose reflect his own demons or being the perpetual third wheel or both? Utter faces away from the group with Valadon at the center, her hand to her chest, between the two men in her life. She stands out with her bright dress against the yellow background. She is the literal center of this family, the heart of it, and the breadwinner. Behind Utrillo is the aged Madeline, the physical resemblance of mother and daughter evident. Valadon’s work was often described by critics using masculine adjectives, like “virile,” which were intended as compliments.

Suzanne Valadon, Marie Coca and Her Daughter Gilberte (Marie Coca et sa fille Gilberte), 1913, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, Lyon, France.

Marie Coca and Her Daughter Gilberte reveals a different side of the mother/daughter relationship. Unlike Berthe Morisot or Mary Cassatt, who often portrayed an affectionate familial relationship, Valadon’s portrait shows a disconnect between the two figures. The woman, lost in thought or her own world, seems oblivious to the girl’s presence. Likewise, the girl utilizes the woman’s legs as a backrest but there is no meaningful touch or connection.

Valadon’s nude paintings differ from those of her male peers. They are seen through the female gaze, through the eyes of the model turned artist. These are paintings of realistic women, with natural shapes and curves. Valadon also depicts pubic hair, which was often omitted as it was thought of as dirty and unseemly (especially on women).

Suzanne Valadon, Adam and Eve (Adam et Ève), 1909, Centre Pompidou-Musée National d’Art Moderne/CCI, Paris, France.

Adam and Eve shows two full-length nudes – one of the first full-length nude self-portraits of a woman and possibly one of the first of a nude male by a European female artist (she added the foliage later). This was painted the year Valadon and Utter met. She depicts them around the same age, with no hints of age on her face. We know this new love revitalized her work, why shouldn’t it give her a youthful glow too? In their secluded grove, Eve/Valadon reaches to grab the apple as Adam/Utter grabs her wrist. Is he helping her pull the apple off the branch or is his grasp forcing her to hesitate?

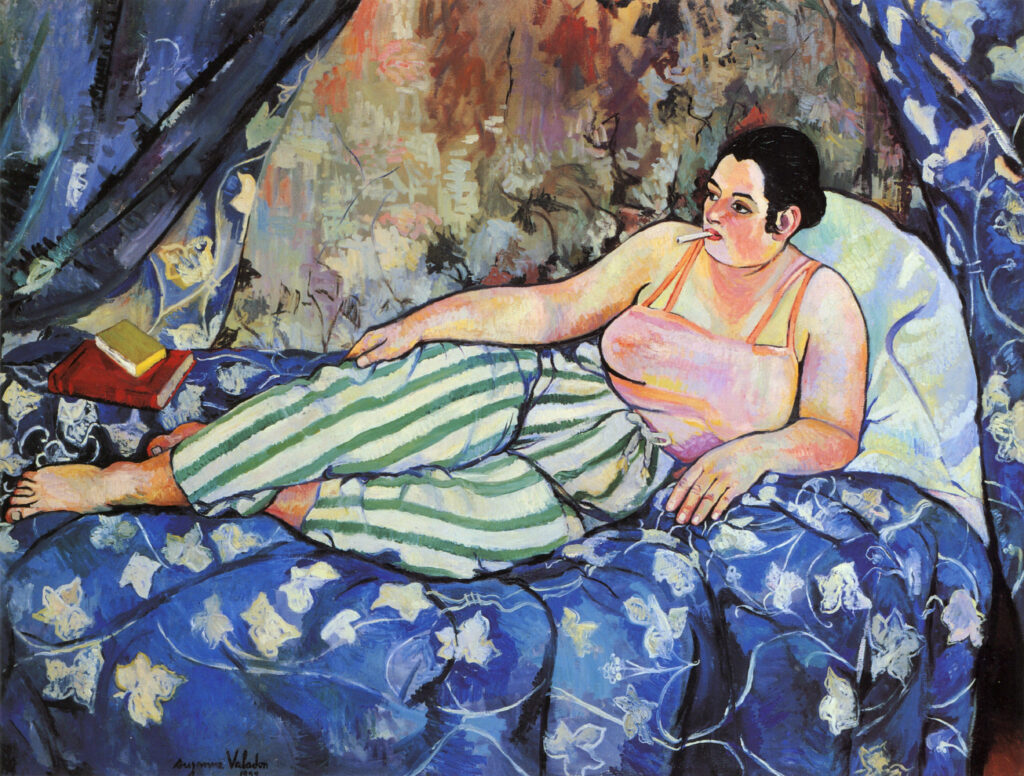

One of Valadon’s most famus paintings is The Blue Room. When I explored the female gaze vs. the male gaze in art history, I debated about using this painting rather than Reclining Nude but ultimately went with the more direct comparison. But this painting could easily have been part of the argument too.

Suzanne Valadon, The Blue Room (Le chambre bleue), 1923, Centre Pompidou-Musée National d’Art Moderne/CCI, Paris, France.

As in Reclining Nude, Valadon’s The Blue Room subverts, again, the traditional pose of a slender nude woman lying outstretched. In this instance, her model is a regular-sized woman, fully clothed, and, importantly, wearing pants. In the 21st century, we take this wardrobe staple for granted but something as simple as pants was not socially acceptable for women at the time, even in this most casual of settings. Unlit cigarette dangling from her mouth, she relaxes with books at her feet – a timeless image, really. Who hasn’t sat like this in the last week, or especially the last two years? The clashing of patterns between the bed curtains and covers with her pants and the wall lead our eyes around the canvas. What is she be looking at? Maybe she’s simply lost in thought?

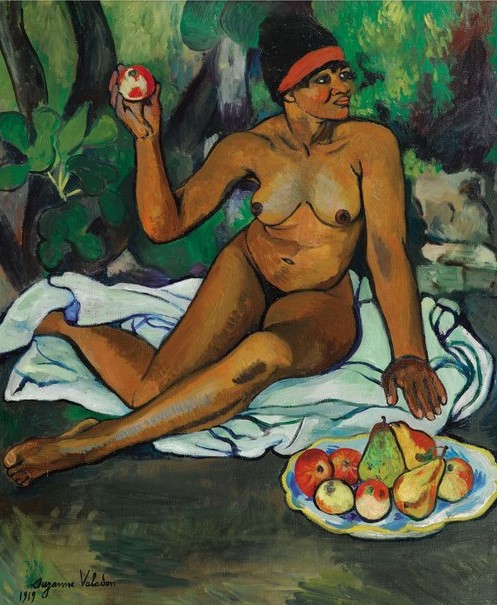

Suzanne Valadon, Seated Woman Holding an Apple (Mulâtresse assise tenant une pomme), 1919, private collection, Miami, FL, USA.

In Seated Woman Holding an Apple, a nude woman sits on a blanket outdoors with a plate of apples and pears next to her. One arm is raised as she holds an apple in her hand. She leans on the other, her head turns as her attention is drawn outside the canvas. Again, we see the body of a regular woman, we see ourselves in her. Valadon depicted this model at least twice, perhaps up to five times, in a series produced in 1919.

Lastly let’s discuss some of Valadon’s still lifes and portraits of Valadon’s acquaintances. The still lifes show vibrant colors and curvaceous shapes. We see that jarring confluence of patterns and colors in Still Life with Drapery and Bouquet. Valadon was still clearly having fun mismatching patterns as seen in the previous year’s The Blue Room.

Suzanne Valadon, Still Life with Drapery and Bouquet (Nature morte a la draperie et au bouquet), 1924, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France.

Likewise, her portrait of Mauricia Coquiot shows a mix of patterns amongst the model’s dress, the curtain, and even the flowers. With her back straight, she looks out at the viewer with an attitude underscored by the dark shadows on her face.

Suzanne Valadon, Portrait of Mauricia Coquiot (Portrait de Mauricia Coquiot), 1915, Centre Pompidou-Musée National d’Art Moderne/CCI, Paris, France.

Suzanne Valadon was 62 years old in her Self-Portrait from 1927. Her image shows a woman who has, unapologetically, lived life on her terms. When she died in 1938, her funeral was attended by leading artists and figures of the day, testament to her artistry and personality.

Suzanne Valadon, Self-Portrait (Autoportrait), 1927, Collection of the City of Sannois, Val d’Oise, on temporary loan to the Musée de Montmartre, Paris, France.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!