A Fire in His Soul: How Paris Changed Vincent van Gogh

In his new book A Fire in His Soul, Miles J. Unger gives us Vincent van Gogh as we’ve never seen him before—abrasive, intransigent, egotistical,...

Ledys Chemin 21 February 2025

To truly understand Suzanne Valadon, we must look at her art. Let’s explore five of her most compelling paintings, each a testament to how her life, identity, and experiences shaped Suzanne Valadon’s creative journey.

Suzanne Valadon grew up in the vibrant Montmartre art scene of late 19th-century Paris. She began her journey as a model for renowned artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Immersed in their creative process, she absorbed their techniques, eventually channeling her passion and talent into her own work. Breaking barriers, she became the first woman admitted to France’s prestigious Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

Suzanne Valadon, Maurice Utrillo Playing with a Slingshot, 1895.

The distinctive style of Suzanne Valadon is already evident in the early works of her career. Eschewing the soft, delicate lines often associated with women artists of her era, she embraced a bolder, more assertive approach, defined by dark, confident outlines. This choice defied conventions and gave her work a raw immediacy that set her apart in a male-dominated art world.

Suzanne Valadon and Maurice Utrillo, c. 1890. Wikimedia commons (public domain).

Valadon often portrayed her son Maurice Utrillo, who would later also become an artist. In this piece, she captures a moment of boyish concentration: a young Maurice, seen in profile, crouches low, his attention fixed on the slingshot gripped tightly in his outstretched hands.

The drawing is a study in simplicity and power. Using minimal but deliberate strokes, Valadon outlines the boy’s bare form, bringing to life the natural curves and faint musculature of his body. The unguarded pose and serious expression lend the image a sense of intimacy and timeless innocence. Through pieces like this, Valadon established her reputation as an artist unafraid to break boundaries, both in her subjects and her technique.

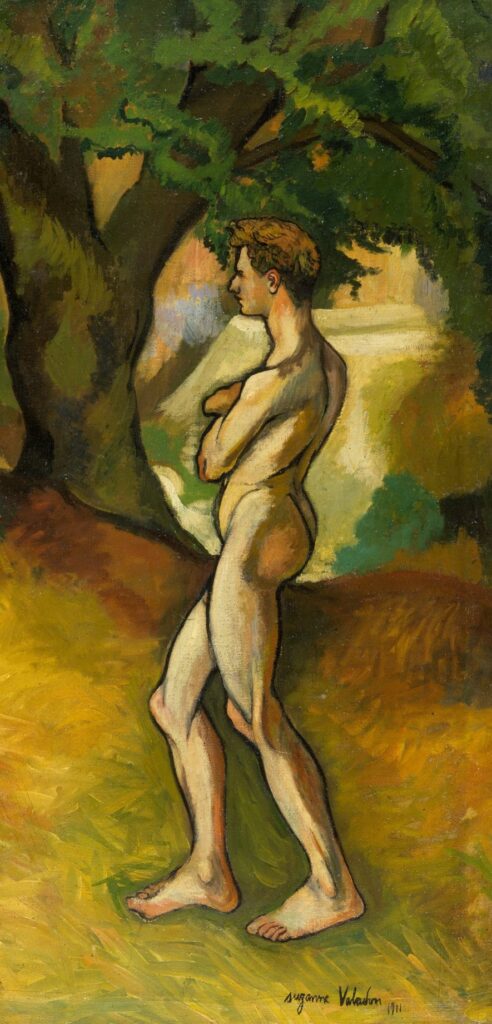

Suzanne Valadon, Joy of Life, 1911, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Another important characteristic of Valadon’s artistic work is her ability to infuse each piece with her distinctive perspective. Even when working with familiar themes, such as bathers in her famous painting Joy of Life, her unique interpretation of the subject is immediately recognizable.

In Joy of Life, the artist presents a landscape featuring four nude or seminude women, their serene interactions observed by a lone nude man positioned to the side. Notably, the male figure, modeled by Valadon’s lover André Utter, adds a provocative twist to the traditional theme of bathers in nature. Utter, whom Suzanne Valadon met through her son Maurice Utrillo, frequently appeared in her work, including notable paintings such as Adam and Eve and Casting the Net.

Suzanne Valadon, Joy of Life, 1911, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Detail.

Some scholars suggest that Valadon’s inclusion of the male figure reimagines a classic motif with her own modern lens. Unlike conventional scenes of idyllic female bathers, the man’s presence shifts the narrative, with some arguing that his role is a near-parody of the “male gaze.” Meanwhile, the women, seemingly unaware of his watchful eye, exude independence and self-possession, subtly challenging traditional depictions of gender and attraction. Ultimately, this painting, like much of Valadon’s work, invites viewers to reconsider the dynamics of sex and desire in art. To delve deeper into Valadon’s exploration of the female versus male gaze, read further here.

Suzanne Valadon, The Abandoned Doll, 1921, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, USA.

Coming to Valadon’s mature style, we observe bold, vivid colors, strong dark outlines, intricate textile patterns, and simplified forms. This can be perfectly exemplified with her work The Abandoned Doll. The figures, posed in slightly awkward positions with distorted anatomy, convey an emotional depth that defines her work.

The girl, wearing nothing but a pink hair ribbon, turns away from the woman, engrossed in her reflection in a small hand mirror. The pink bow in her hair subtly mirrors the ribbon adorning a doll discarded on the floor, a poignant symbol of childhood left behind. Through this visual connection, paired with the girl’s developing body, Valadon hints at a pivotal moment of transition in her life—a shift from innocence to self-awareness.

Although the figures are known to be Valadon’s niece and the girl’s mother, the artist deliberately avoids framing the work as a portrait. Instead, the painting unfolds as a universal narrative, evoking the bittersweet journey from childhood to adolescence, a theme that resonates with many viewers. True to Valadon’s distinctive approach, her depiction of the female form in this piece is unidealized and active, challenging traditional portrayals of women as passive, sexualized objects. Moreover, her personal and unapologetic style continues to set her apart, offering a refreshing counterpoint to the conventions of her time.

Suzanne Valadon, The Blue Room, 1923, Centre Pompidou-Musée National d’Art Moderne/CCI, Paris, France.

Another important work in Suzanne Valadon’s oeuvre is The Blue Room, which is one of her most famous paintings. At its center is a confident, full-figured woman, reclining on a welcoming daybed with books scattered nearby. She is wearing loose green-and-white striped trousers and a tank top that closely matches the warm tones of her skin. In that way, she teases the idea of nudity without fully embracing it—a deliberate and provocative choice.

A cigarette hangs nonchalantly from the woman’s lips as she gazes off to the right, her expression introspective, as though lost in thought. Her right arm rests assertively on her hip, while her left supports her effortlessly against a pillow. Overall, the composition captures an air of casual self-assurance.

Interestingly, Valadon echoes Titian’s Venus of Urbino or Manet’s Olympia. However, she turns this familiar composition on its head. While traditional nudes painted by men often present women as objects of sexual availability, Valadon’s subject radiates self-assurance and complexity. Her strong sense of sexuality is just one facet of a much richer, multi-dimensional personality. Correspondingly to her mature style, she employs bold colors, intricate patterns, and a richly decorative background.

Suzanne Valadon, Self-Portrait with Naked Breasts, 1931, private collection.

This self-portrait by Suzanne Valadon stands out as a groundbreaking work, blending the nude and the self-portrait in a way that is both strikingly realistic and deeply honest. Through this piece, Valadon offers an unflinching depiction of aging, shedding light on an often-overlooked aspect of womanhood.

Suzanne Valadon challenges societal norms by asserting her own perspective on her body—one that is not confined to the ideals of youth. Instead, she presents herself as active, present, and unapologetically engaged in her work well into later life. In doing so, she disrupts the traditional association of nudity with sexual availability. Her nude is not an object of desire but a profound statement of identity. Through this courageous work, Valadon redefines both the nude and the self-portrait, showcasing the power of art to explore deeper truths about individuality and womanhood.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!