Masterpiece Story: Buddha Dated 338

Buddha dated 338 is a masterpiece of Buddhist art and Chinese art with deep historical significance. It exemplifies the early blending of Indian...

James W Singer 14 December 2025

From opening its door in 1973 to being part of the UNESCO World Heritage and one of Australia’s most iconic symbols of the modern era, the Sydney Opera House has made a name in the architecture scene despite years of challenges from its initial design to its completion. Here, we will trace that history.

In the 19th century, Sydney Harbour already had a theater, albeit small, British, and mundane. As anticipated, it became a bane of the cityscape in the 1900s, once the desire to have their own performing arts center escalated among Sydney locals, for prominent figures and common people alike. However, this dream remained on hold until the 1950s, when three driving factors made it a reality:

Firstly, the post-World War II era saw a significant wave of immigration from Europe, which led to an unprecedented economic boom in Australia.

Secondly, the arrival of Sir Eugene Goossens in Sydney played a pivotal role. As an English composer and conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Goossens found the acoustics at the Sydney Town Hall insufficient. Identifying a need, he thus became a passionate advocate for a new venue that ideally could be equipped with superior acoustics and at least 3500 seats.

Thirdly, John Joseph Cahill assumed the role of Premier of New South Wales (the Australian state governing Sydney) in 1952. Cahill, a former civil engineer and labor activist, shared Goossens’ view of creating an accessible and more enjoyable space for music. He announced an opera house project shortly after his election.

Aerial view of Sydney Harbour from above Millers Point and Walsh Bay, 1950s. Archives of the City of Sydney.

In 1955, the site for the new building was selected. Bennelong Point, south of Sydney Harbour, was named after Aboriginal Australian Woollarawarre Bennelong. The British colonists used the location to commemorate Bennelong’s work as an intermediary for them to learn the Aboriginal language and tap into Australia. The following year, Cahill launched an international competition for “a National Opera House at Bennelong Point.” Among the 223 or over participants from 28 countries were 12 drawings from a 38-year-old Danish architect, Jørn Utzon.

In January 1957, a committee of four started to review the proposals: Ingram Ashworth, Professor of Architecture at Sydney University; Sir Leslie Martin, professor and a Royal Festival Hall project contributor; Cobden Parkes, National Government Architect; and Eero Saarinen, renowned Finnish-American architect and designer.

The actual sequence of events and decisions that led to the selection of the finalist remains under debate. However, it was believed that Saarinen’s verdict was particularly decisive; the TWA Passenger Terminal at John F. Kennedy International Airport he designed in New York in the mid-1950s had made him a big name.

On January 29, 1957, Utzon was announced the winner. His design, while deemed “controversial” for its trailblazing originality, was also recognized for its numerous merits.

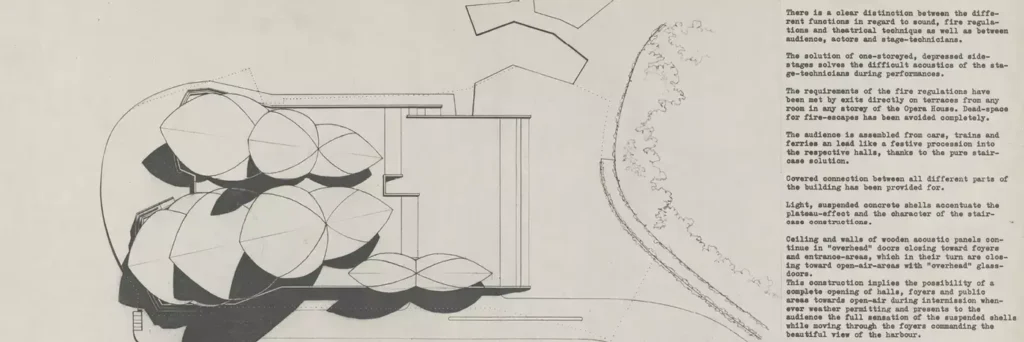

Jørn Utzon, Competition drawing, 1956, State Archives and Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, Australia. Sydney Opera House.

Unlike his contemporaries, Utzon did not depart from “function over form.” He likened the project to a sculptural form. To let the structure best interact with its surroundings, he then strove to make the Opera House’s visible from every vantage point along Sydney Harbour. That unique and unparalleled structure resulted from his genius and, at the same time, was an expression of the life experiences that shaped him.

We can trace Utzon’s approach to the 1930 Stockholm International Exhibition that drove his parents to rebuild their own home. During the exhibition, the family discovered Scandinavian architect Gunnar Asplund, who would remain a crucial influence on young Utzon. Then, Utzon traveled to the Americas, where he further enriched his architectural philosophy. In the North, encounters with architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright left lasting impressions, while in the South, he absorbed the beauty and underlying concepts of Aztec and Mayan temples. Yet the landscape in his native land, for example, the Kronborg Castle on the waterside near the house where he grew up, was also a shaping force behind his ideas. Utzon’s Sydney Opera House combined all these; the design intended to seamlessly blend ancient cultures and built forms with modern concepts, complementing its Sydney Harbour waterfront location with “shells” or roofs projecting out made of precast concrete.

On March 2, 1959, construction started with a ceremony. It was Stage One—which would address the building’s base and structure.

However, two significant problems surfaced early on. Firstly, the geology of Bennelong Point, initially assessed before the competition, turned out to contain loose alluvial deposits permeated with seawater instead of the more manageable sandstone mass. This unforeseen foundation propelled the construction team to increase their initial budget. Secondly, the weight of the roof was left out of the calculation.

These issues could have been solved prior. But Cahill, eager to realize his dream building, perhaps did not want to cause trouble or attract enemies. Months later, as he lay on his deathbed, Cahill called Norman Ryan, the Minister for Public Works at that time, requesting him to carry on with the project.

Stage One was completed in 1963, slightly later than anticipated but within the budget. It’s important to note the pivotal role played by Ove Arup, the supervising engineer. Arup used an undulating shape in the Concourse area beneath the Monumental Steps, where it was initially designated to have a colonnade to support the structure above. His modifications led to a form so elegant that Utzon, impressed, later dubbed it “Ove’s invention.”

Sydney Opera House under construction, 1960s. Sydney Opera House.

From 1958 to 1962, Utzon and his team tackled the Opera House’s visionary roof. Pertinent drawings underwent radical revisions and restructuring. Engineers grappled with mathematical expressions to visualize the shells. The process was particularly challenging. Each shell’s footing had a bend at a specific angle, which required additional calculations to put the parts together and, consequently, higher costs.

In almost an epiphany, Utzon came up with the spherical solution. He realized that all the varying curvilinear forms could come from a single geometric form or a module and then be assembled—similar to how joining multiple planes together at an angle could end with a dome. This breakthrough made the Sydney Opera House stand out stylistically and structurally in the history of 20th-century architecture and beyond.

Utzon designed these roof components to match the blue of the Harbour and the sky with his choice of gloss tiles that were not mirror-like. To that end, he drew from the ‘engobe’ technique of glazing found in Chinese and Japanese ceramics. Based on it, he then created the Sydney Tile.

As challenges from the early stage of construction became resolved, Stage Two began in 1963. However, at that point, the relationship between Utzon and the New South Wales Government had turned sour. Most of it was cost-related. At the onset of Stage Two, the projected expenditure was already four times the initial estimate.

Francesco Bandarin, Sydney Opera House (Australia), particular of the tiles of the roofs, 2007. © UNESCO.

In 1965, Davis Hughes assumed the role of Minister for Public Works. He soon took over the finances and suggested revisions to Utzon’s drawings, including those for the building’s interior. Hughes further maintained that the architect should communicate with the New South Wales government before building prototypes and testing his projects to receive payments.

The situation reached an impasse until February 1966, when Hughes and Utzon confronted each other. However, neither party was willing to yield. Utzon, constrained financially, threatened to resign. It was taken lightly by the Premier. Yet Utzon eventually stepped down, and Hughes had to make shift without him. This decision was subsequently made public to both the press and Parliament.

Despite being offered a consulting role, Utzon never returned to Australia, even to witness the completion of the building. This rift also strained his friendship with his former colleague, Ove Arup.

In April 1966, construction started again with a new crew. Hughes appointed architects Peter Hall to oversee design, DS David Littlemore for supervision, and Lionel Todd for documentation.

Hall, a young and talented Australian architect, met Utzon after receiving a travel scholarship to Europe. He later worked for the New South Wales Government Architect Ted Farmer at the Department of Public Works. Hall accepted the role on a phone call with Utzon, who confirmed he would not return.

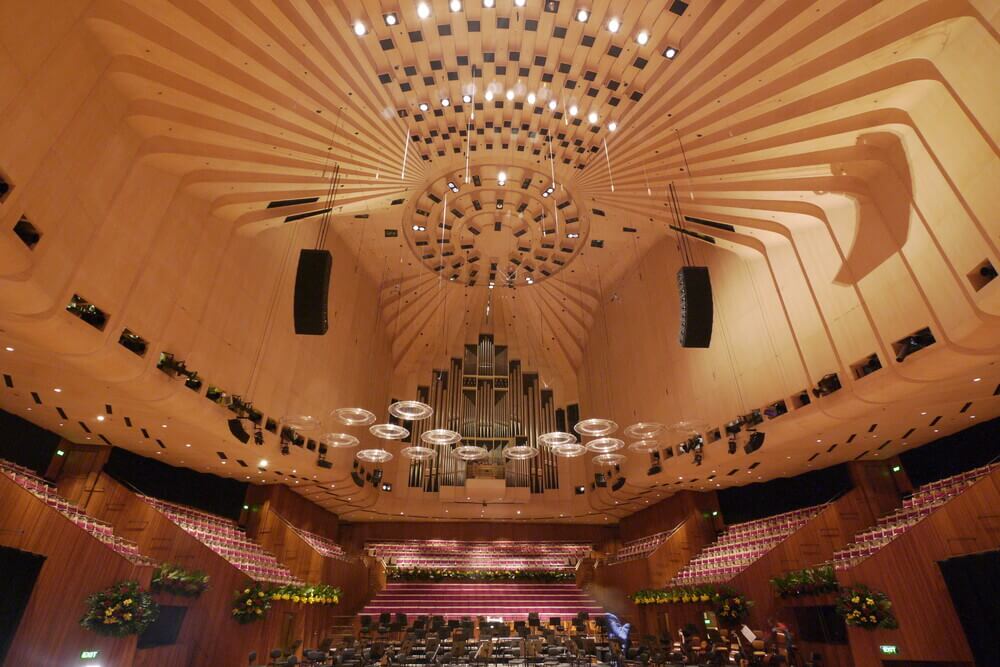

With Stage Two ending in 1966-67, Hall had to plan Stage Three to design the interiors and foyers. Hall intended to follow Utzon’s plans before realizing how limited the documentation his predecessor had left. There were only sketches but no comprehensive working drawings. To complement the missing information, Hall spent a significant amount of time in Europe, consulting Utzon’s associates and studying concert halls in the Western world.

Despite a challenge in and of itself, Stage Three provided a common ground for the ideas of both Utzon and Hall. The former had projected curtains of glass that appeared suspended from the roof shells. After Utzon’s departure, Arup and Hall revisited this idea, considering it alongside engineering and acoustics. The end product managed to balance the conceptual side with functionality while it helped maximize the viewing area with fewer support elements.

The Concert Hall was probably a milestone of this phase. Making it a single-purpose area for symphonic music might differ from the dual-purpose design anticipated, yet the compromise worked best to address the aesthetic and acoustic concerns.

Julian Wyth, Sydney Opera House (Australia), particular of the interior, 2010s. © OUR PLACE The World Heritage Collection, UNESCO.

At the official opening ceremony on October 20, 1973, Queen Elizabeth II opened the doors of the Sydney Opera House. That day concluded an eventful course of designing, building, and finally realizing an aspiration, as well as marked the beginning of a transition of Bennelong Point, which has shifted from a postcolonial legacy to a place for the arts.

Besides accommodating musicians and musical performances, the Sydney Opera House has figurative paintings. In particular, these are Salute to Five Bells (1971) by Australian contemporary painter Johns Olsen and Possum Dreaming(1988) by late Warlpiri artist Michael Nelson Jagamara. In a way, the Sydney Opera House is like one of the Australian Museums!

Moreover, the opera house displays four tapestries: Le Corbusier’s Les Dés sont Jetés or The Die Is Cast (1960), John Coburn’s Curtain of the Sun and Curtain of the Moon (1973), and Jørn Utzon’s Homage to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach(2004).

In June 2007, the building appeared on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a masterpiece of the 20th century. During its first 50 years, Sydney Opera House has welcomed events and artists from all over the world.

Ko Hon Chiu Vincent, Sydney Opera House, 2015. © Ko Hon Chiu Vincent, UNESCO.

Our story, Sydney Opera House’s website.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!