Easter Holy Week and The Crucifixion

The final days of Holy Week are traditionally associated with the trial and execution of Jesus, culminating in his entombment in Jerusalem before his miraculous resurrection on Easter Sunday. The image of the Crucifixion has become an instantly recognisable symbol of humanity’s cruelty, coupled with a positive belief in its salvation. Although early Christian Art tended to focus on the reassuring imagery of Christ’s preaching or triumphant return, the depiction of a suffering Jesus on the cross would eventually become a potent sign of sacrifice throughout visual culture.

One of the earliest representations of the Crucifixion appears on the wooden doors of the Santa Sabina Basilica in Rome. Although the preoccupation with pain and horror seem wholly absent, this 5th Century portrayal is a clear attempt to express divine surrender for the hope of mankind.

The Art of Pain

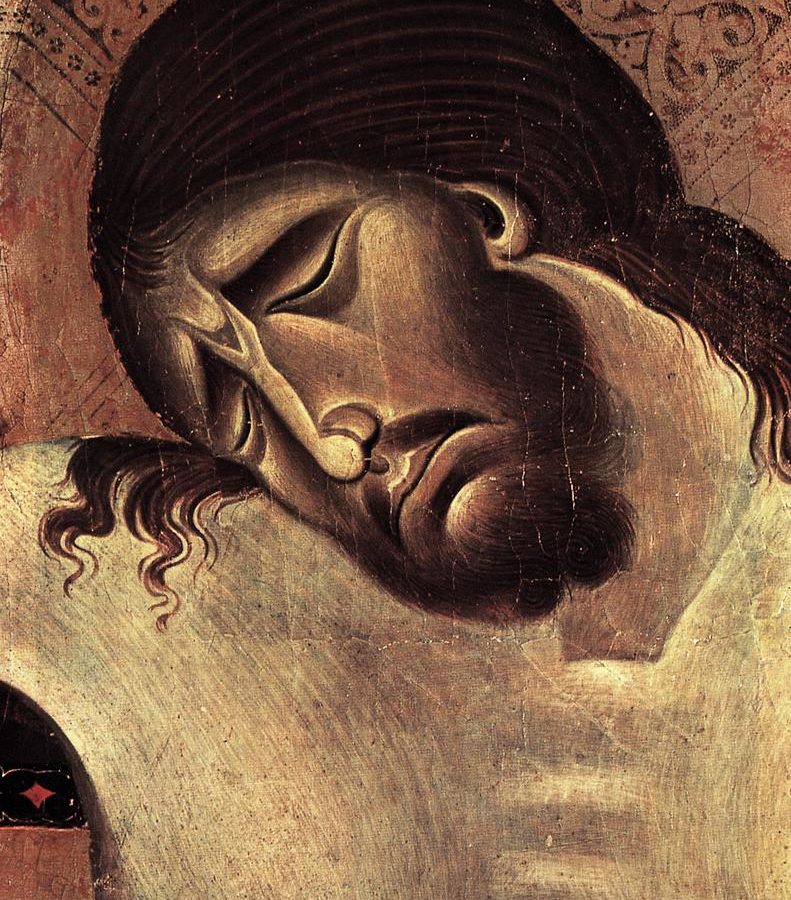

Once his death as an earthly being became a powerful emblem to inspire devotion, conveying the physicality of Christ’s pain grew more widespread. The medieval Gero Cross is an early monument to his agonised martyrdom. Originating from around 965 -70, it is housed within Cologne Cathedral in Germany. The lifeless slumped head and contorted torso magnify Christ’s agonised execution, becoming conventional in later Gothic and Renaissance art and standard iconography thereafter.

The detail from this painted crucifix attributed to Florentine artist Cimabue is from the late 13th century. It further heightens the spiritual empathy that informs the heart of Christian faith, allowing the viewer to identify with Christ’s plight through his punished expression.

This preference for enhanced narrative drama through extreme suffering would allow artists to exercise power over a humbled congregation. Visual interpretations of the Crucifixion would evolve into more elaborate and complex forms to express not only the torment of Jesus, but the anguish of humanity.

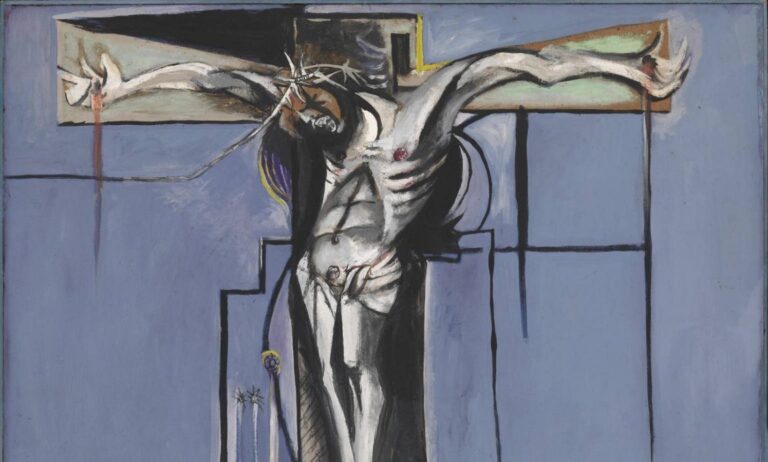

Sutherland’s Commission

In 1944, British artist Graham Sutherland was commissioned by the Vicar of St. Mathews Church in Northampton to paint a scene from Christ’s Passion. Commonly known as The Agony in the Garden, this is a familiar episode in the history of art. However, gripped by the idea of attempting his own version of the Crucifixion, Sutherland managed to convince his patron that a modern rendering of Christ on the cross would be a more suitable option. The subject seemed to echo his concerns with the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, in particular the carnage of familiar terrain and emerging footage of emaciated holocaust survivors.

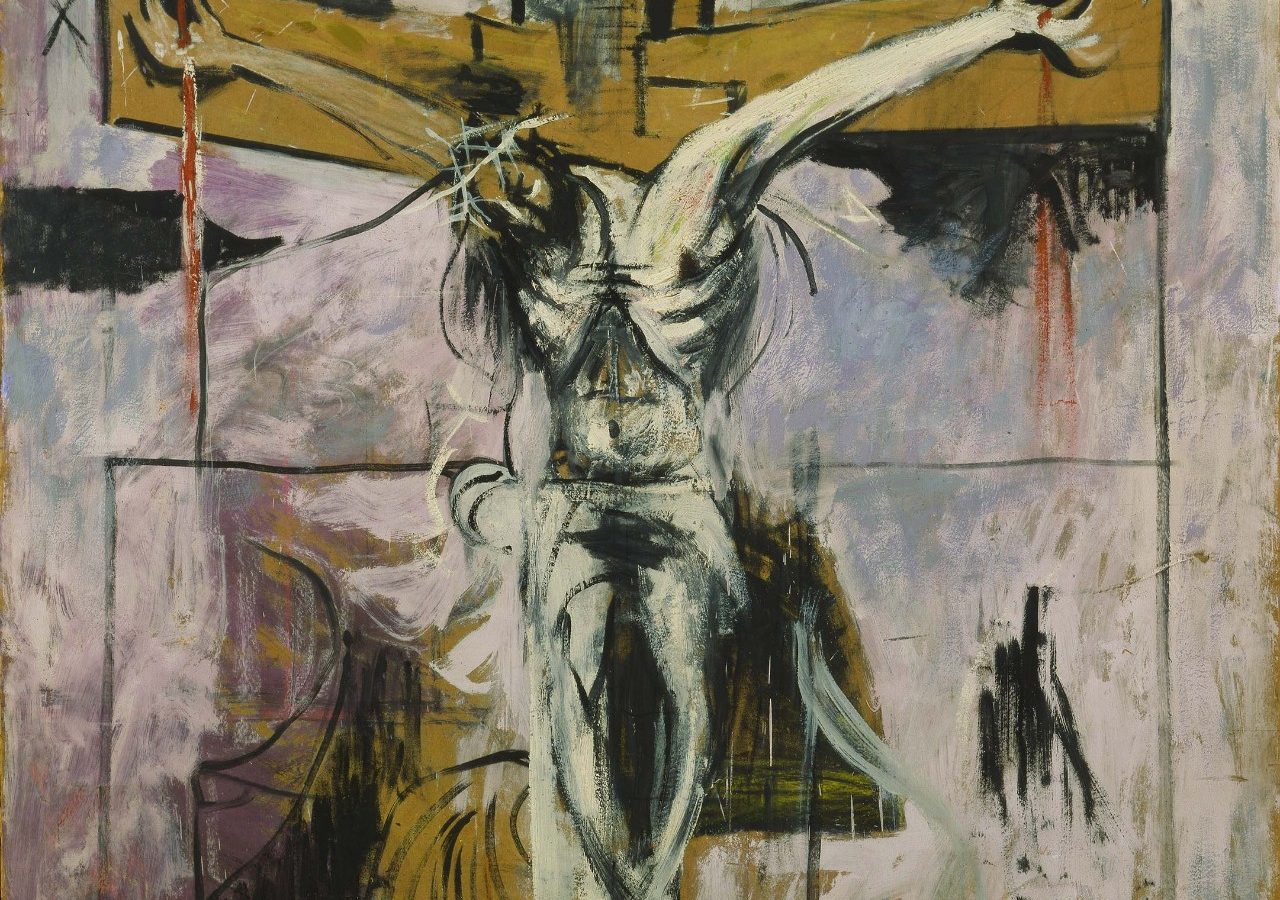

Versions by Francis Bacon

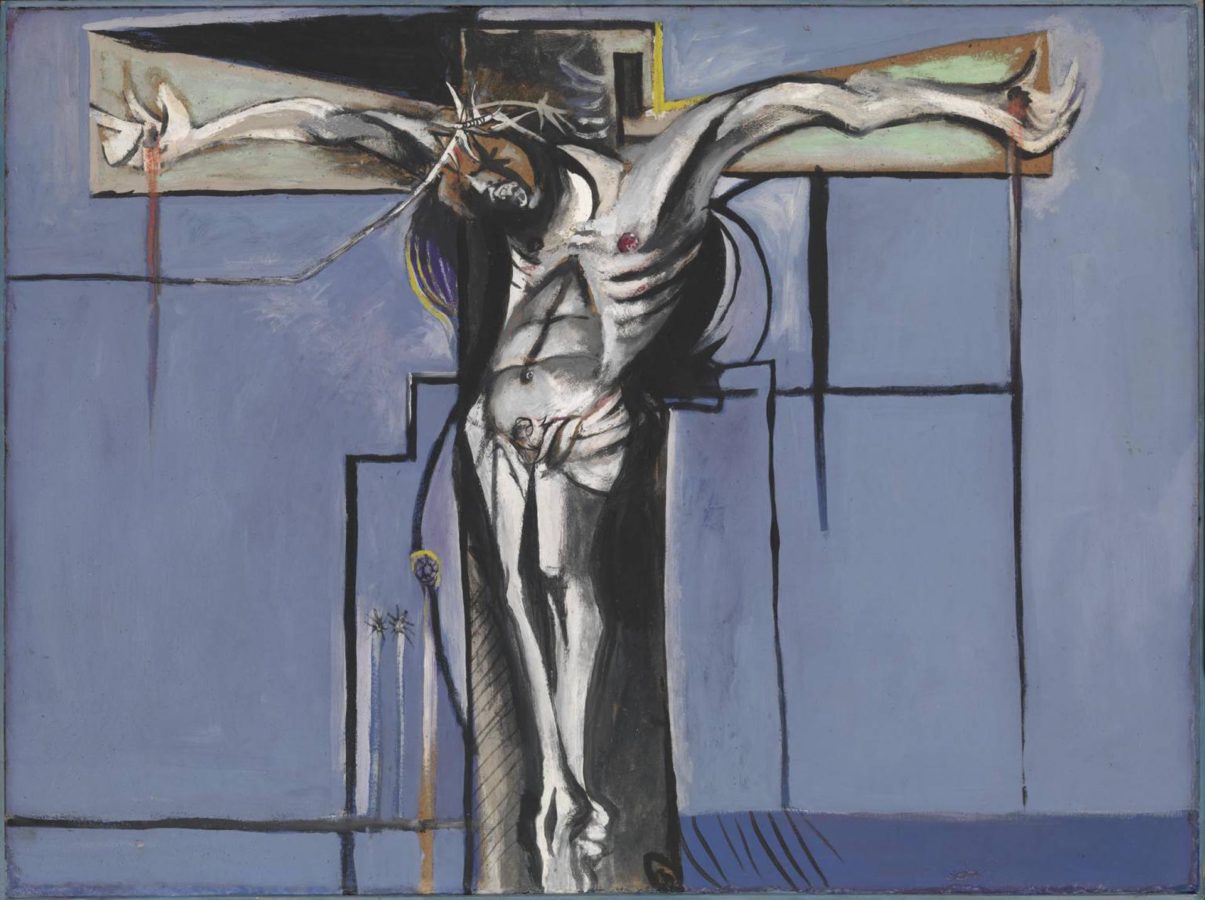

Fellow contemporary Francis Bacon had offered up his own depictions of the Crucifixion in 1933 and 1944. Sutherland was a great admirer and supporter, but whilst Bacon’s ghostly cadavers and nihilistic ogres suggest the butchery of war, the human element that would eventually inform Sutherland’s piece is absent. Bacon’s treatment of Christ’s traditionally crucified form is translated as a hauntingly splayed creature and his later studies for figures at the foot of the cross provide a nightmarish insight into our own fears and instincts. Sutherland’s concerns presented a distinct contrast in terms of human hope and endeavour.

Sutherland’s Landscape

For a painter not commonly associated with figurative portrayal, the Crucifixion seemed to pose a unique challenge to Sutherland’s artistic approach. The scale and subject matter were also unfamiliar to an artist normally allied with landscape and nature. However, a recent role as an official war artist had enabled him to investigate the destructive reality of his environment, translating war torn tragedy into tortured forms that suggest human desolation and fear. Ruined houses, fallen lift shafts and wrecked locomotives became emotionally charged simulations of contorted grief; personal emblems of intense hardship and misery. These visual explorations into a shattered terrain would eventually pave the way for his dramatic studies for the Crucifixion.

Nature too appeared to provide a revised energy for Sutherland. Obsessive studies of thorn heads from this period directly inform the Crucifixion commission; the angular, twisted muzzles paraphrasing Christ’s cruelly mocking crown. Depictions of deformed trees and branches also echo the wooden cross and its familiar contorted victim.

Picasso’s Influence

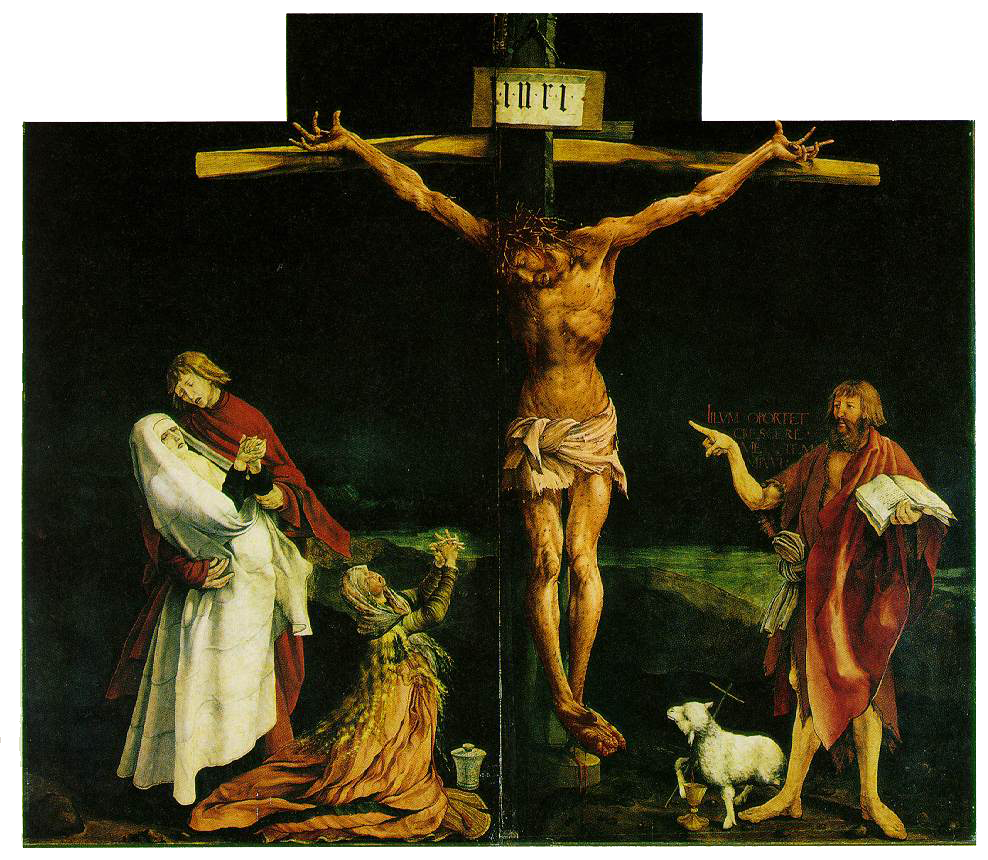

Sutherland had converted to Catholicism in 1926 to marry fellow Goldsmiths student Kathleen Barry. In the tortured frenzy of his Crucifixion series he demonstrates a very real empathy with Christ’s personal distress to achieve a stunning intensity. The influence of Picasso on his creative thinking was immense. Sutherland’s debt to the Spaniard’s Guernica (1937) assisted his attempts to visually convey the struggle between life and decay. Picasso’s own investigations into the contorted Christ of Matthias Grünewald’s 16th Century Isenheim Altarpiece also provided Sutherland with inspiration for his own tortured rendition.

Obsessive studies for the Crucifixion in art reflect our own fascination with this ancient symbol, ensuring human experience throughout history continues to be condensed into this iconic religious scene. We are reminded that Easter is a time for reflection as well as celebration, a festival of hope and renewal through sensitivity and compassion.

Find out more: