Abaporú: a painting that was a birthday gift from a wife to a husband, from Tarsila do Amaral to Oswaldo de Andrade. This work was a symbol of the loving and intellectual connection between two artists, and it also became a powerful symbol of modern Brazilian art that merged and digested local and European styles and themes in an act of (re)creation.

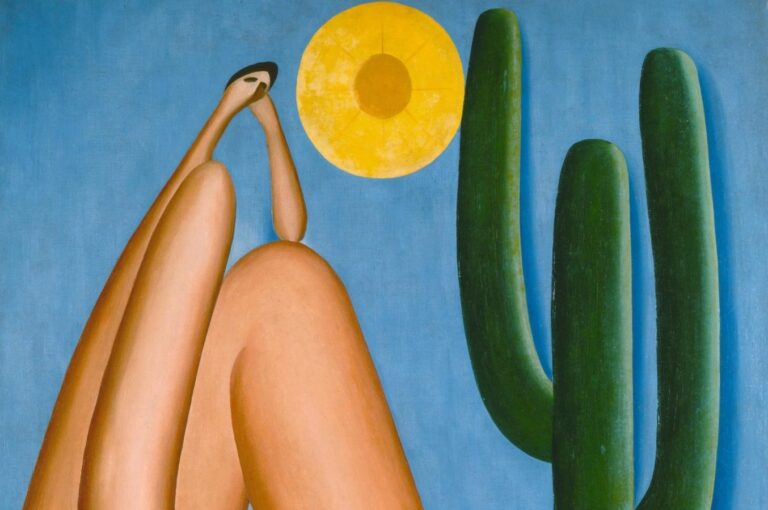

It was a painting that must have enticed strong feelings at the time, when Brazil wanted to be perceived as a modern and rich country. Contrary to this aspiration, Abaporú showed a portrait of a bare, sexless, ageless, gigantic and distorted creature – perhaps even a monster – sitting under the sun next to a cactus.

Abaporú, the title of the work, means in Tupi-Guarani – the language of a local native tribe – cannibal, “a person who eats other people”. The deformed figure doesn’t resemble anything that exists in reality: It is painted with a small head and large hands and feet, and a disproportionate body next to the schematic sun and cactus. This gentle giant has eyes, but no mouth and ears. It is naked, in a position similar to Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker, its one hand laid on its head, slightly twisted towards the viewer, while the disproportionately larger body is turned to the side, towards the sun and the cactus on the right side of the composition.

According to Oswald de Andrade, the painting shows a human being in a state of nature, that of the cannibal. Tarsila, on the other hand, said that the monstrous being is a product of her imagination inspired by the stories told to her by the black nannies at the plantation where she grew up.

Abaporú became an important symbol of the artistic and cultural movement called movimento de antropofagia, started by Oswald de Andrade’s Canninbalist Manifesto in 1928. In that manifesto, Andrade proclaimed what should be the new principles followed by Brazilian artists. He wished that any new art (including literature and visual art) should feed on the different influences, native and European. He wanted to invite Brazilians to cannibalize: to swallow and digest foreign inspirations without any hesitation and with total dedication to the process of the modern cultural creation in the new Brazil. Andrade accepted the existence of different cultures and applauded the natural process of cross-cultural inspiration and appropriation.

Abaporú was created in 1928, two years before the military coup d’état of Getúlio Vargas, in the last moments of the Old Republic which transformed the country from a society and economy based on slavery and agriculture to a more urban, industrial and crisis-prone country. The naked body of a strange creature at the center of the painting, close to nature rather than to culture or to other beings, was a strong, brave and unapologetic declaration of the essence of vitality in Brazilian life, according to Tarsila do Amaral.

The dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas rejected this avant-garde and shocking interpretation of what it means to be Brazilian and instead supported the traditionalist, nationalist and conservative artists. In the sixties, when another military dictatorship took power in Brazil, Abaporú, the anthropophagic movement and Tarsila herself became idols of the new artistic movement– tropicalia. The leaders of this countercultural movement – such as Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa and Helio Oiticica – often evoked Tarsila and her art as their inspiration.

When we look at Abaporú now, we see the most expensive work of Brazilian art, bought in 1995 at Christie’s auction house for 1.4 million USD by Eduardo Costantini, the Argentinian art collector and creator of the Museo de Arte Latinoamericana in Buenos Aires. We also see one of the most important paintings in Latin American art, depicting and resolving the fundamental dilemma in many Latin American cultures – how to come to terms with our hybrid and mixed nature and origin.

Learn more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”0300228619″ locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/51p7O15NCRL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”87″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”B0000EDGHT” locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/51vZCyf7SGL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”82″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”110″ identifier=”8489935874″ locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/21Khcimd2BQL.SL110.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”89″]