Thierry Mugler’s Art of Fashion: Avant-Garde and Iconic

Thierry Mugler’s art redefined the boundaries of fashion, blending creativity, drama, and innovation. His bold silhouettes and futuristic...

Errika Gerakiti 30 December 2024

Would it surprise you to learn that 59% of American women have at least one tattoo? That’s compared to 41% of American men. Perhaps unsurprising is that millennials are the generation most likely to have them. For a practice that was once considered particularly taboo for women, we have quickly made up for the lost time. At the end of the 19th century, women with tattoos were almost unheard of, but they did exist! Some women had a small and dainty tattoo hidden away, never to be seen. Meanwhile, others made tattoos a career.

Quick note: this article focuses on women in the USA. I look forward to learning about women and tattooing elsewhere!

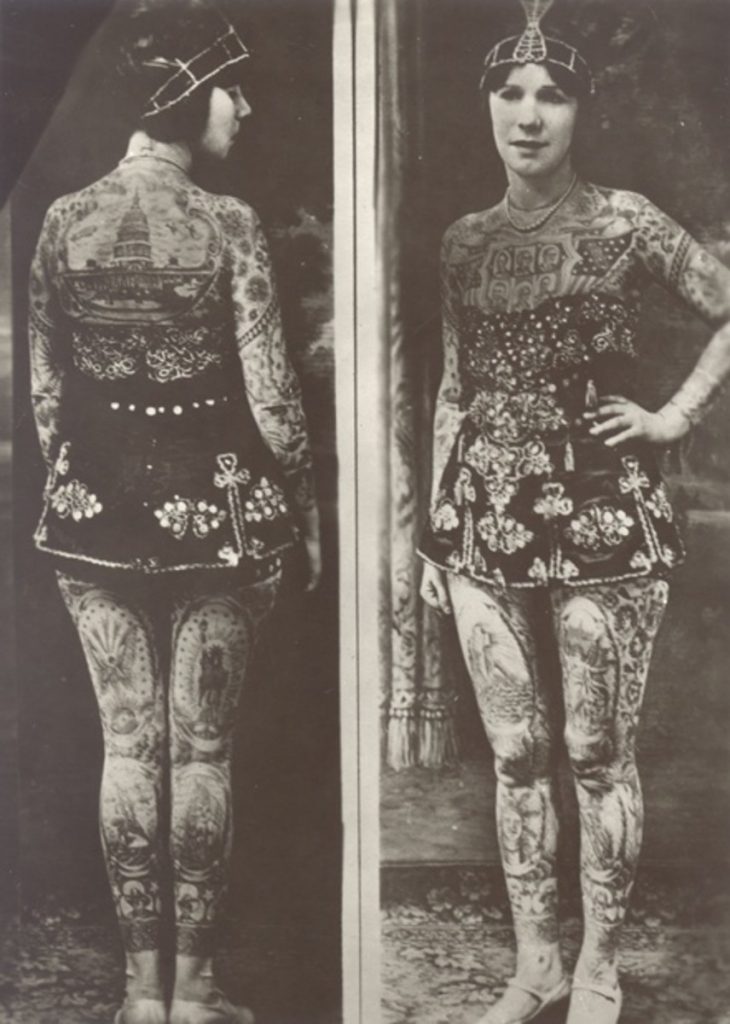

In the past, having one tattoo was rebellious, being almost completely covered was something else, which was true for both men and women. But it probably goes without saying, it would have been even more so for women. Those women that were covered from ankle to wrist could hide it without anyone ever knowing.

Artoria Gibbons, ca. 1920s, Real Photo Postcard by Empire, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Schiffmacher Tattoo Heritage via CNN Editions.

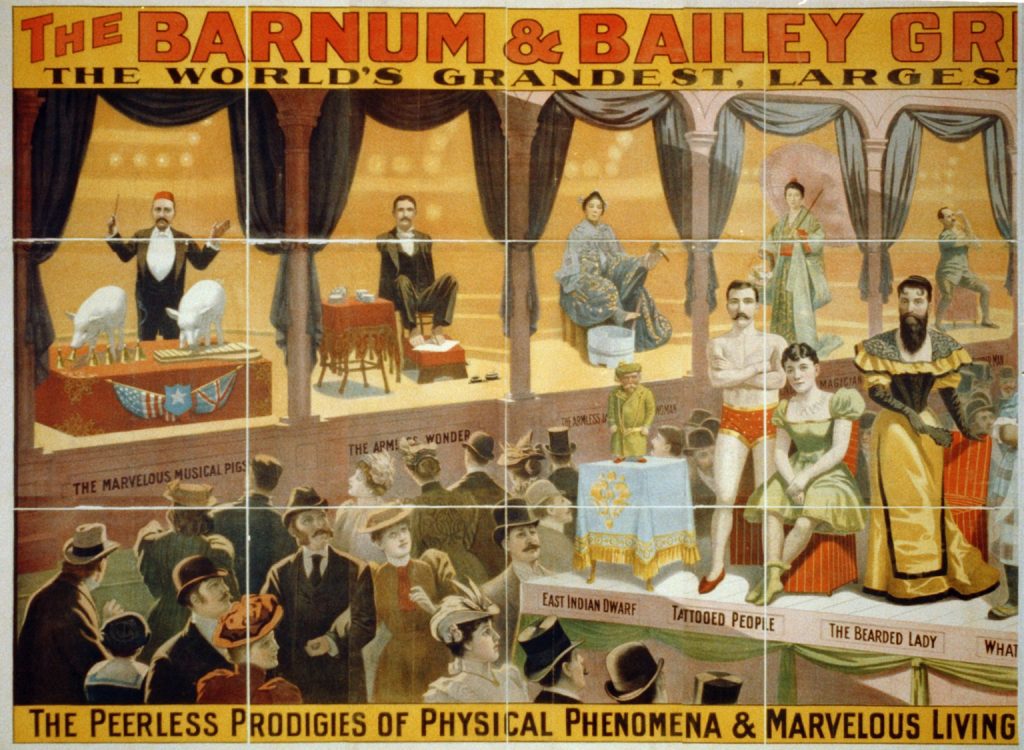

In the United States, at the end of the 19th and in the early-to-mid 20th centuries, a popular form of entertainment was curiosity, or dime, museums that became destinations in their own right when visiting places like New York City or Coney Island. There were also sideshows that traveled with circuses, visiting Small Town in the USA.

Both types of shows featured “exotic” people that were gawked at by a paying public. The quotations around exotic are, of course, purposeful. These were often people who were exploited by the show’s owner, people who were different, physically or culturally. For each of the individuals, placed in a row on a dais above the audience, elaborate backstories were often fabricated and designed to be as intriguing as possible.

The manufactured backstories of the Tattooed Lady generally seemed to provide a justification as to why she was tattooed. She couldn’t say that she simply liked having her body decorated. Instead, there was often a kind of victimhood, a life-or-death situation, like being a hostage of Native Americans. Towards the end of the 19th century, when conflicts with Indigenous Peoples were still fresh in the public psyche, it was an “us vs. them” mentality that played on the audience’s sympathy.

Promotional Flyer of The Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth, featuring The Tattooed People, 1899, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain). Detail.

There was also a sexual element to the Tattooed Lady. First, she often wore revealing outfits. Revealing for the time, that is. This being the waning days of the Victorian era, respectable women were generally covered from wrist to ankle. When Tattooed Lady was at work, she wore short, strappy dresses or bodices and shorts that showed off her legs, arms, and upper chests.

Secondly, a Tattooed Lady was “not like other girls.” She was a woman who, by the nature of her career choice, appeared to live according to her own rules and seemed to have an independence other women didn’t have. Tattoos implied the opposite of what society (of any time period) dictated: obedience, modesty, and chastity. Instead, the Tattooed Lady could be seen as flouting conventional ideas, and that always includes sex.

Without going too deep down the rabbit hole, there were also practical, economic reasons why a woman ended up as a tattooed performer. There were only a few options open to women who needed to earn an income and it was something different from the traditional prescribed route. In many cases, there was a sense of adventure as it allowed her to travel around the country when she might not otherwise have had the chance.

It would be hard to know who was officially the first Tattooed Lady, but there are two women who vied for the title: Irene Woodward and Nora Hildebrandt.

Photograph of Irene Woodward, from “The Tattooed Woman” in The New York Times, March 19, 1882. Afflictor.

Irene Woodward has the distinction of being the earliest documented Tattooed Lady. As written in Amelia Klem Osterud’s The Tattooed Lady: A History, Woodward was highlighted in The New York Times on March 19, 1882, with the headline “The Tattooed Woman.” The article described her as “bashful about being looked at the way, never having worn the costume in the presence of men before.” She was appropriately, almost modestly, shy being on display. It goes on to include some of her art:

Around the neck was observed a floral necklace. Dependent from this was a bunch of roses in full bloom drooping until their graceful forms were lost beneath the lace edging of the bodice. The rising sun was illustrated on each shoulder and the arms were covered with stars, hearts, floating angels, wreaths, harps, crosses, a full-rigged ship, and various mottoes. The young woman’s back, it was said, was completely covered with a large cross, heart, and anchor. Upon the lower limbs were pictures very numerous and complicated.

Woodward worked as a Tattooed Lady for over 20 years, touring the United States before going international. In many of the major western European cities, she entertained a range of classes and people from regular museum-goers to royal families. Her likeness was even immortalized in that barometer of celebrity, wax museums. She died at the age of 58 in 1915.

Charles Eisenmann, Nora Hildebrandt, c. 1880, New York Historical Society, New York, NY, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

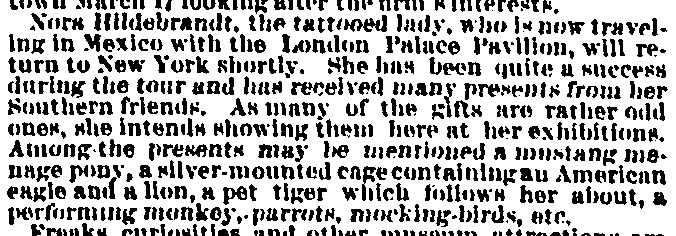

Nora Hildebrandt first appeared in newsprint on March 22, 1884 in the New York Clipper, though her promotional booklet (which should be taken with a grain of salt) lists her earliest performance as March 1, 1882. The article in the Clipper writes about her exhibitions in Mexico and that:

She has been quite a success during the tour and has received many presents from her Southern friends. As many of the gifts are rather odd ones, she intends showing them here at her exhibitions. Gifts she received included a pony, an eagle, a lion, a tiger (which follows her about), a monkey, parrots, mocking birds, etc.

Mention of Nora Hildebrandt in the New York Clipper upon her return from Mexico, 22 March 1884, New York, NY, USA. Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. Detail.

For a time, Hildebrandt was in a common-law marriage with Martin Hildebrandt, a well-known tattoo artist who did all her work. It appears she worked mainly out of New York, joining various dime and curiosity museums, with the occasional overseas trip. She died in 1893, at the very young age of 36.

What is interesting about these two women, as Osterud points out, is the way they were treated. Rather than simply bawdy entertainment, they were regarded as “respectable ladies”. As she writes, it made the venue a more welcoming environment, one that was safe and fun for the whole family.

Women were not just the sideshow’s arm candy; they were also the tattoo artists. Maud Stevens Wagner was both a Tattooed Lady and tattoo artist and Ruth Weyland had her own shop. Around 1906 Wagner was taught by her husband, which is reminiscent of female artists throughout art history having to be tutored by family members. Also like those earlier artists, Wagner advertised herself using her initials so as to hide her sex. She ended up teaching her daughter how to tattoo as well.

A side note that these two women, inarguably, have the coolest photos around.

It is important to note that the electric pen wasn’t invented until 1890. For our first generation of performers discussed here, their tattoos were applied by hand with an inked needle. This makes us think twice when looking at some of these images – it would have taken an exhaustive amount of time, and patience, to get tattooed in by traditional methods.

For Woodward and Hildebrandt, available colors were limited to two: India ink and Chinese vermillion. Designs ranged from what is typically seen on shop walls today (known as “flash”) such as stars and flags to Leonardo’s The Last Supper. There were actually a few Last Suppers – I imagine it’s a good way to take up space! As artists were constrained by the technology they had, the lines weren’t particularly strong and as Osterud writes, “crude”.

Artoria Gibbons and her Last Supper tattoo, ca. 1920, Real Photo Postcard by Empire, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Medium.

Osterud writes that it is unknown whether their bodies were completely covered since we can’t be sure what was under their costumes. There’s only one known photograph of a topless Tattooed Lady who does have a clock on her stomach but that is too small a sample size to be definitive.

On behalf of all ladies with tattoos, I tip my hat to our daring foremothers.

“Miscellaneous,” in New York Clipper, March 22, 1884, New York, NY, USA, p. 6. Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. Accessed 4 Aug 2022.

Amelia Klem Osterud, The Tattooed Lady: A History. Denver, CO, USA: Speck Press, 2009.

“The Tattooed Woman,” in The New York Times, 19 March 1882. Afflicted. Accessed 4 Aug 2022.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!