Madness in Art: A Powerful Connection

Madness and art have long shared a profound and powerful connection, where the boundaries between genius and instability often blur. Many acclaimed...

Maya M. Tola 28 October 2024

Love them or loathe them, tattoos are a global phenomenon. Inserting pigment under the skin for decorative or ritualistic purposes has been around since prehistoric times. Tattooing is a close relative of scarification and piercing, and examples exist across every continent. Read about tattoos in history and their appearance in arts and culture.

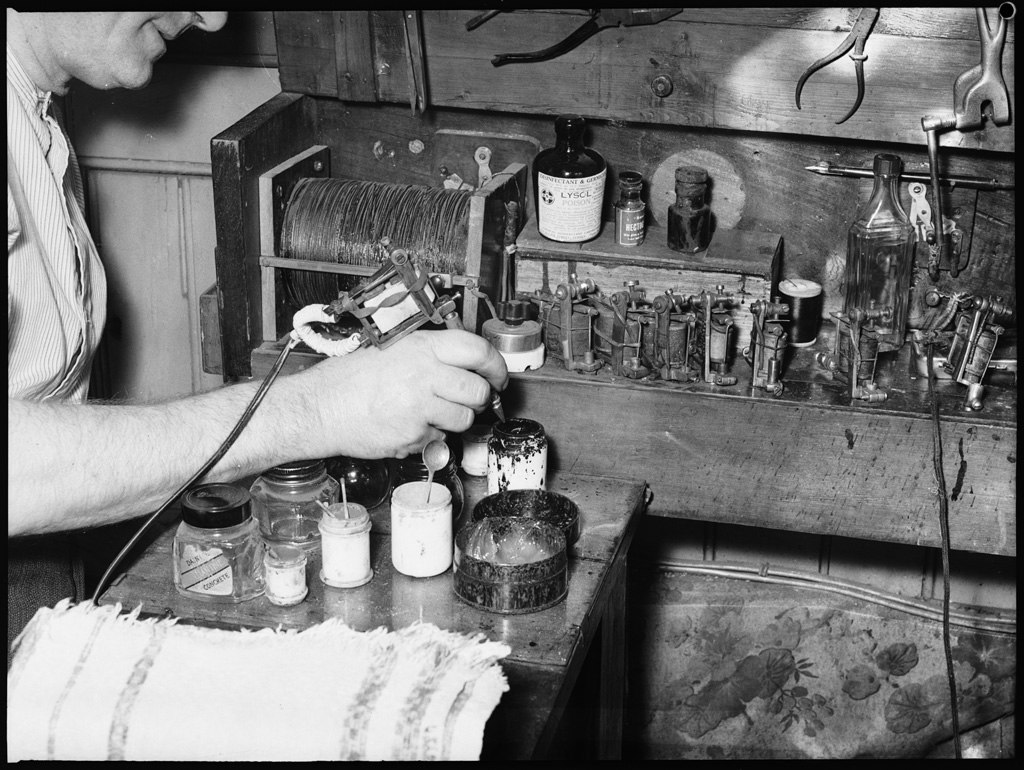

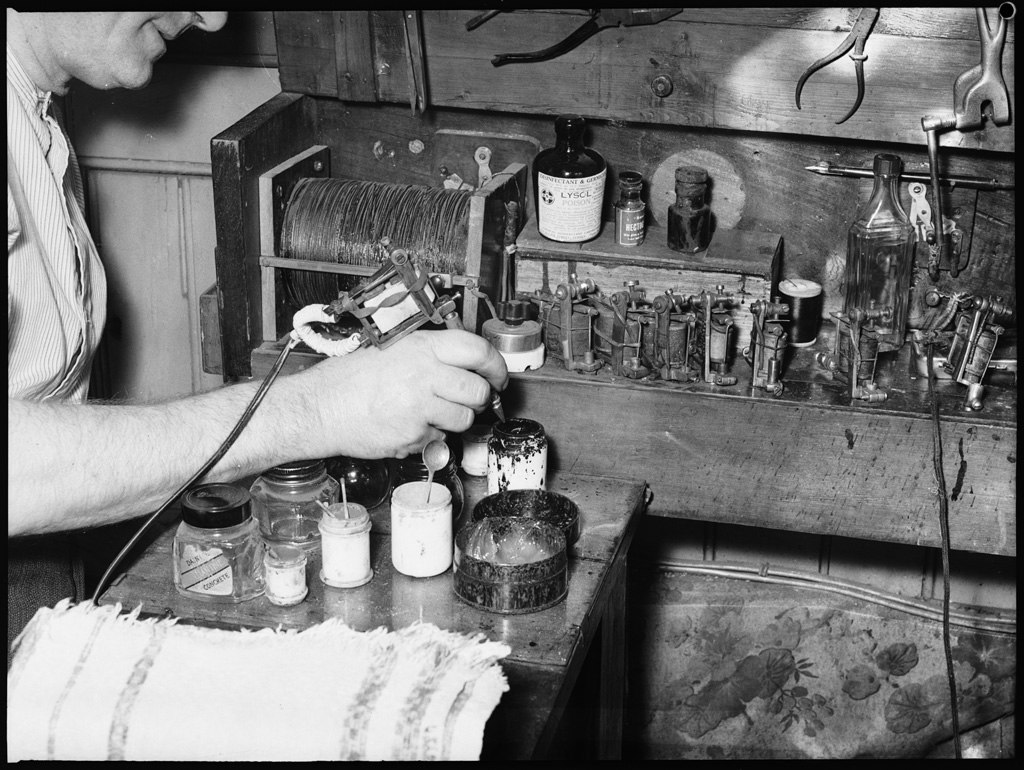

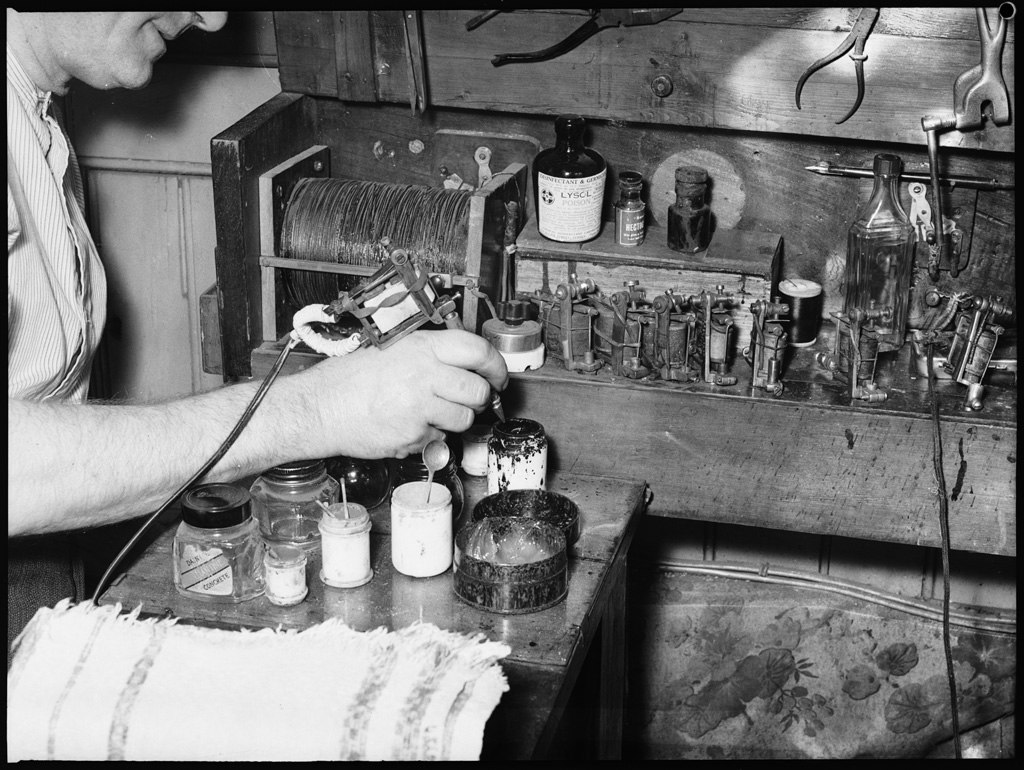

Polynesians gave the English-speaking world the word “tattoo” which is derived from the Samoan word “tatau”. Modern tattooing uses some highly specialized electric tools. Traditionally, however, a tattoo would be created using thorns, fish or animal bones, teeth, oyster shells or obsidian. Color might be added through the use of ash, soot, woad, plant extracts, copper, burnt nuts, wood and even gunpowder.

The earliest evidence of tattoo history is found in clay figurines with tattooed faces, discovered in tombs in Japan which date back to 5000 BCE. If you’re looking for actual tattooed skin though, then we must move forward in time to 3300 BCE when Otzi the Iceman was buried in a glacier near the Austro-Italian border. Otzi had over 50 tattoos on his body, possibly made from soot, each matching points on the body we associate with the practice of acupuncture.

Mummies from 2000 BCE in Ancient Egypt also had tattoos, especially high-ranking women. The Romans named an early Celtic tribe Picts literally meaning “painted people”. Pilgrims across time would be tattooed with images to commemorate their travels. In Polynesia, high-ranking Samoan women would bear tattoos. Meanwhile, in New Zealand, facial Ta moko work is instantly recognizable.

Sailors from around the time of James Cook brought souvenir tattoos home from the various tribal peoples they met on their travels. This practice spread rapidly across global seaports. The indigenous tattoos they encountered on their travels fascinated Westerners. Sadly their imperialist desire to acquire and display everything that piqued their interest meant that decorated tribal peoples were treated like commodities.

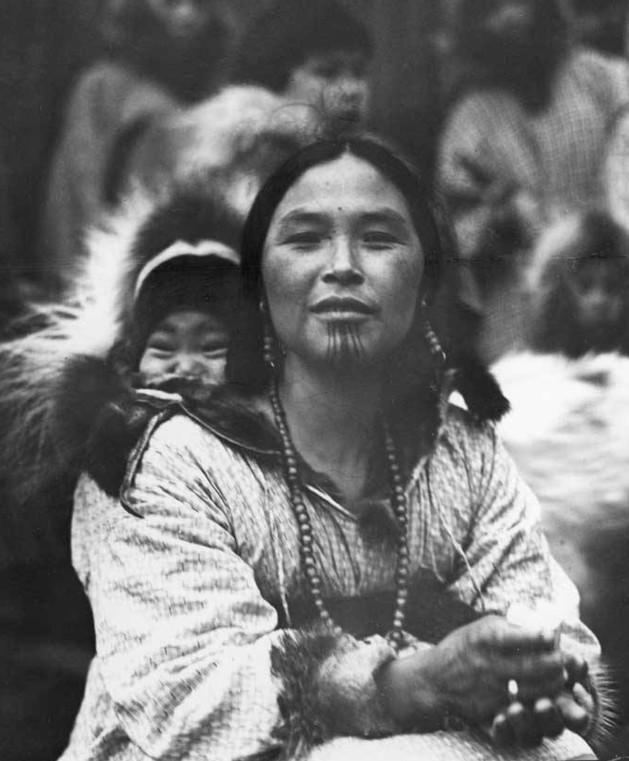

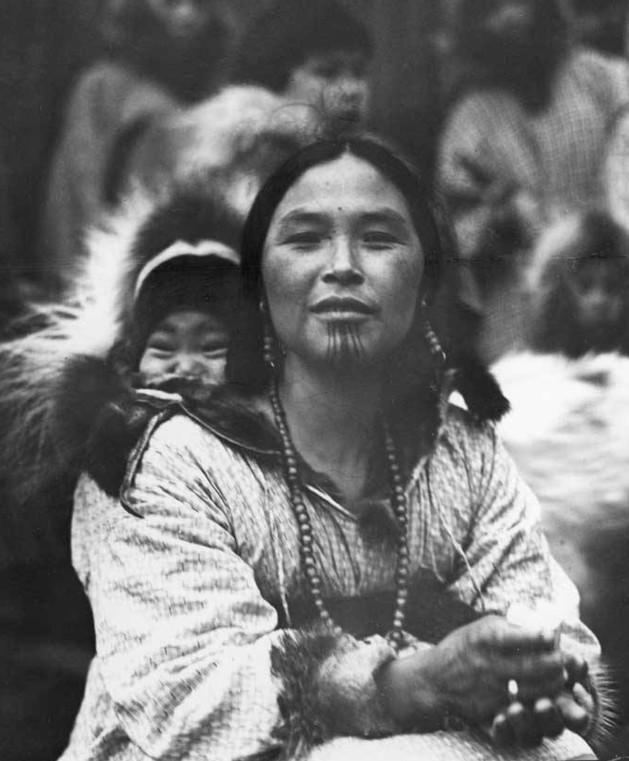

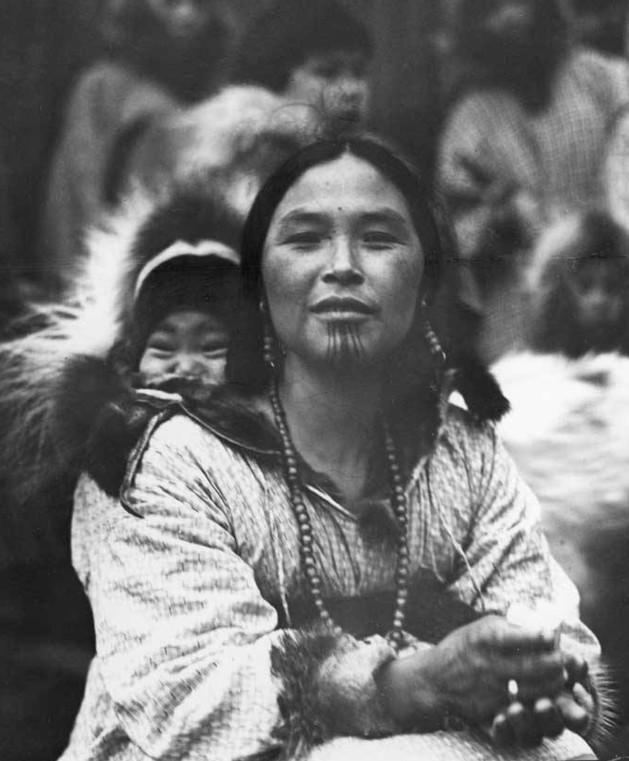

In 1565, French sailors abducted a tattooed Canadian Inuit woman and her daughter, putting them on display in Antwerp. Sir Martin Frobisher, seaman and privateer, did the same with an Inuit man from Baffin Island. When the man died shortly after arriving in London, Frobisher returned to Baffin Island and abducted another family, all of whom also died from Western illnesses shortly afterwards.

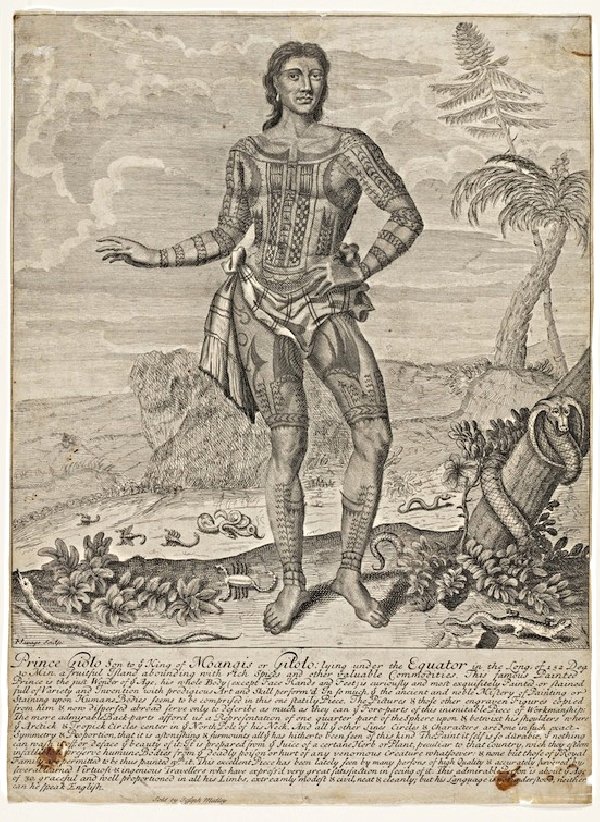

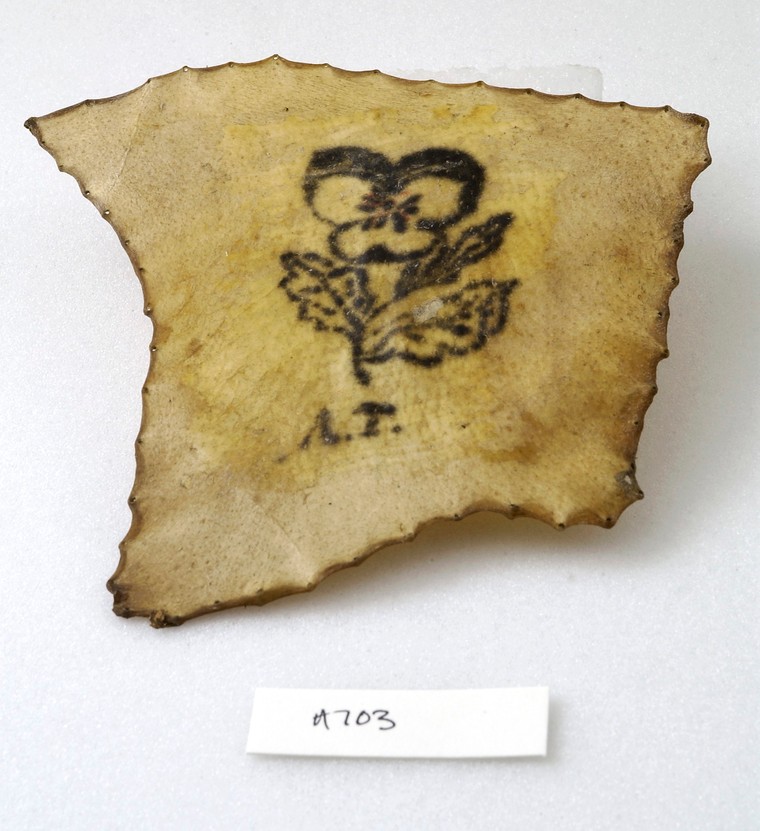

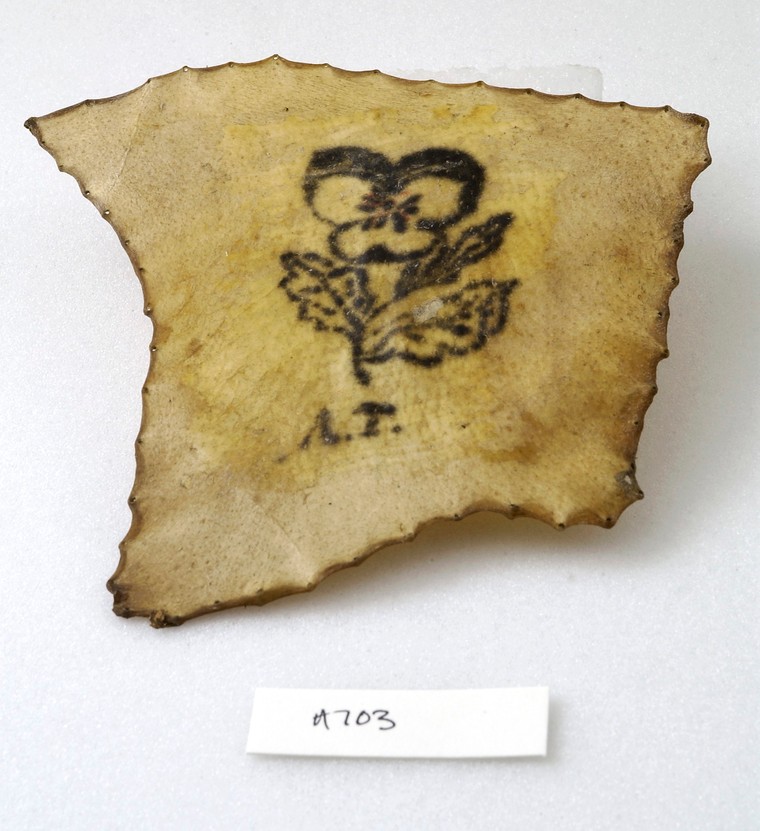

The Painted Prince is an infamous example of this kind of slavery. In 1691 explorer William Dampier brought a tattooed, Filipino man called Jeoly to London. He then sold him to a pub, for public display like a caged animal. (As a side note, Dampier was the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe). Dampier renamed Jeoly “Prince Giolo”, presumably to increase interest and value, and also invented lurid stories about his life and history. Sadly, Jeoly contracted smallpox and died in 1692 at the age of 30. To add further insult, his tattooed skin was preserved and displayed in the Oxford Anatomy School, although is now declared “lost”. It is presumed that the skin deteriorated because of poor preservation techniques, however the trauma and humiliation meted out by the British on Jeoly is truly horrifying. The critique of Western World approach, fetishisation and inhuman treatment is also portrayed in the movie directed by Markus Schleinzer Angelo (2018), which tells the similar story of an Afrikan boy chosen to be a mascot for Viennese court.

Freak shows, carnivals, and circuses might include a heavily tattooed lady as an attraction, such was the horror and fascination of an unconventional and transgressive woman! Meanwhile, in stark contrast, tattoo tea parties became a fashionable way for “nice” ladies to spend an afternoon (although the results of their inking was usually well hidden). Rumor has it that even British royalty Queen Victoria and George V got themselves a tattoo! The freak show ladies were not from this comfortable elite though – these women were seen as immoral, often sexualized, with few if any other chances in life.

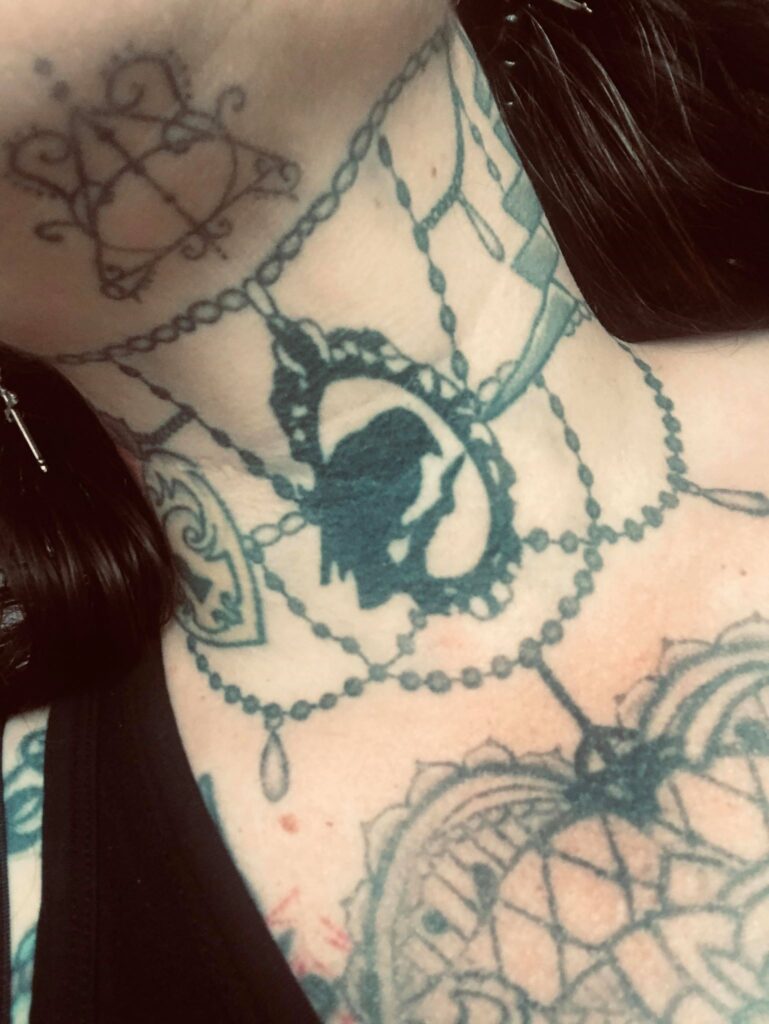

However, there were a handful of well-known tattooed ladies who seemed to clearly enjoy the performance art of their profession and who earned decent sums of money. Lady Viola (Ethel Martin) was known as “The Most Beautiful Tattooed Woman in the World” and was also a tattoo artist herself. She worked until she was well into her seventies. Maud Stevens Wagner (our headline image) takes the title of the first female tattoo artist in the US. She worked by hand, without a tattoo machine. She is also credited with taking tattoo artistry from the coastal areas across United States of America. Women today have much more freedom to ink their bodies as they please, to glorious effect.

For some people, tattoos have a rather unsavory reputation. For them, a tattoo is a stigma with negative connotations of criminal subcultures and gang membership. Meanwhile, it is estimated that currently 1 in 4 or even 1 in 3 people have a tattoo. Tattoo-inspired designs are finding their way onto bedding, rugs and tableware. There was even a limited edition Totally Stylin’ Tattoos Barbie – very collectible, despite the controversy around its release! Could it be argued that tattooing is now on its way to becoming a social norm?

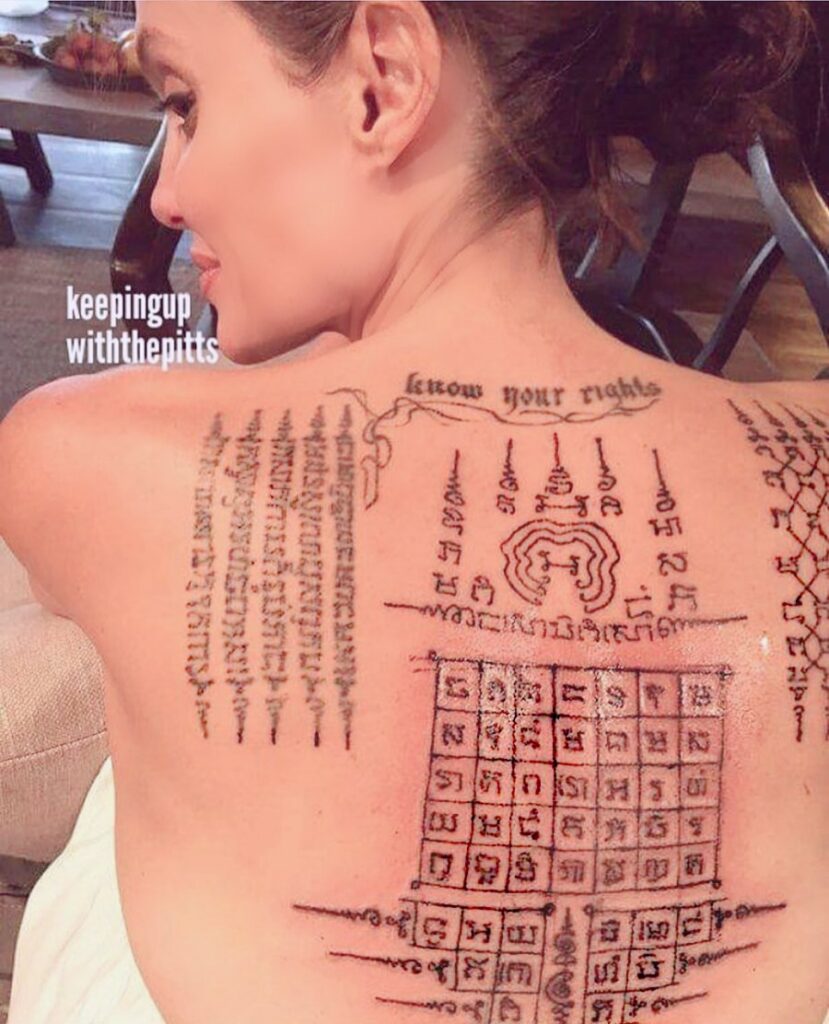

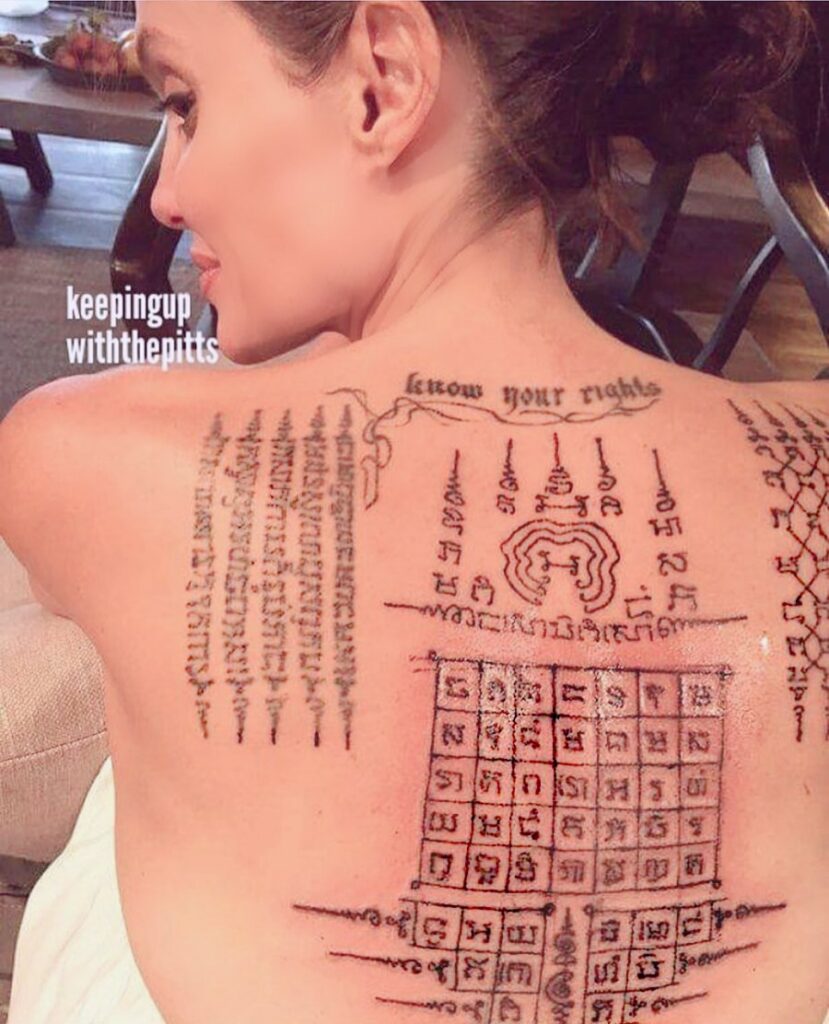

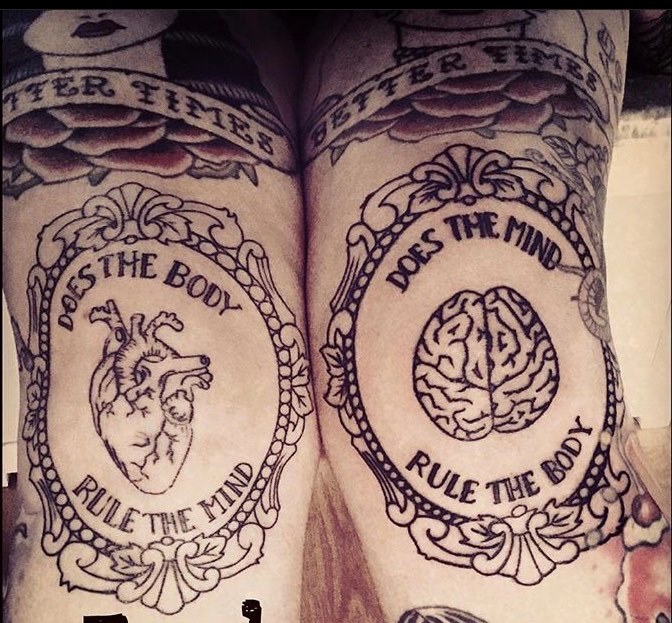

Celebrity tattooing has certainly brought the practice into the mainstream. Now there are multiple reality TV series about the life and times of the tattoo artists. Gossip columns abound with stories of the latest tattoo spotted on the bodies of film and music stars, some of which can hardly be called art. The self-referencing body tattoos of David and Victoria Beckham, Alyssa Milano, and Nicole Richie already have acres of coverage, so the less said about them the better. But what about the more thoughtful or artistic ink?

Actress Megan Fox had a Nietzsche quote inked onto her rib cage: “Those who danced were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music”. However, the Queen of celebrity body art is surely Angelina Jolie. Sporting multiple tattoos, she popularized the tribal dragon motif and has a Thai tiger, inked in the traditional way with needles, chanting, and blessings.

Singing star Rihanna has an image of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti on her rib cage and the Goddess Isis on her chest. The unusual falcon tattoo on her ankle was inspired by a 4th century BCE hieroglyphic inlay exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Often referred to as a “gun-shaped” tattoo, in fact, it has a much more positive meaning – the falcon represents the Egyptian god Horus Behdety, who ensured that the sun rose every morning.

Before body art became fashionable in the West, and while tattooing was banned in many cities, the late, great Janis Joplin was inked by artist Lyle Tuttle. A decorative symbol representing the liberation of women was tattooed on her wrist way back in the late 1960s.

Tattoos appear in several film history greats. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is surely too obvious, but how about Guy Pearce in Memento? The amnesiac investigator writes notes to himself in the form of tattoos on his body. And who can forget the mad, bad Robert Mitchum with his Love/Hate knuckles in Night of the Hunter?

In literature, we have the macabre tale of Skin by Roald Dahl. This is the tale of a homeless man Drioli, whose back has been tattooed by a young man who later becomes a famous artist. I won’t spoil the story, but in typical Dahl fashion, it involves a very unsettling ending. It was later made into a short film for the British TV series Tales of the Unexpected, starring Derek Jacobi. Short stories by Ray Bradbury were made into a Rod Steiger film The Illustrated Man, where we dive into a nightmare sci-fi world in which the tattoos on a man’s body foresee the future.

Shelley Jackson went one step further, her “story” is being written, one word at a time, across the bodies of over 2,000 volunteers. Ineradicable Stain is still in progress, but only the participants will ever read the full text of the story.

In Wales, artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins started his Skin /Skora project in 2014, where he collaborated with volunteers, designing a tattoo for them, which would then become part of a wider exhibition. Like all the best tattoos, the artworks were intended to be personal and meaningful, and involve dialogue between the artist and the subject.

There are tattoo artists who also work in fine art and this is not surprising given the similarities of skill. Both require technical mastery, a talent for drawing, and cultural relevance. Famous paintings themselves have also been transformed into body art. The Great Wave by Hokusai pops up quite a lot, as does Starry Night by Van Gogh. Gustav Klimt certainly seems to have a tattoo-based following, and line drawings by Pablo Picasso (Dove of Peace, Head of a Woman) work out quite beautifully. Google your favorite artist with the word tattoo and browse away!

Of course, as well as the personal choice of illustrating the body, there is a darker side to tattoos. The Greeks and others used them to mark slaves. Meanwhile, the scar of the Auschwitz tattoo, used by the Nazis as an identification system, is still deeply inked into our collective consciousness. A horrifying postscript to the Nazi story is Ilse Koch, who was the wife of a Nazi commandant during the Holocaust. She was accused of taking skin souvenirs from concentration camp victims with distinctive tattoos.

How does the mainstream art world deal with tattoo art? Well, it’s a mixed bag. Not usually fans of anything that might be considered “folk art” curators are also faced with the question: How do you display skin art in a conventional art museum? Also if you can’t buy or sell it, dealers are spectacularly uninterested.

Mainstream art galleries occasionally hold exhibitions of the history of tattoo designs. The Museum of Croydon, UK, held the Beyond Skin exhibition. In 2016 the Museum of London held their Tattoo London exhibition. Richmond’s Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has featured life-sized photographs of traditional Japanese tattoo art captured by the photographer Kip Fulbeck.

Musée du Quai Branly in Paris explored tattooing as an artistic medium in 2014 with Tatoueurs, Tatoués. Works were specially commissioned for this event, and imprints were taken of living models. Chicago Freaks and Flash at Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, US, in 2010 featured vintage circus banners and early tattoo designs. The Field Museum, also in Chicago, held an amazing exhibition in 2017, alongside a real-life tattoo parlor. And in 2019 The Immigration Museum at Museums Victoria in Australia explored tattoo as self-expression in Our Bodies, Our Voices, Our Marks.

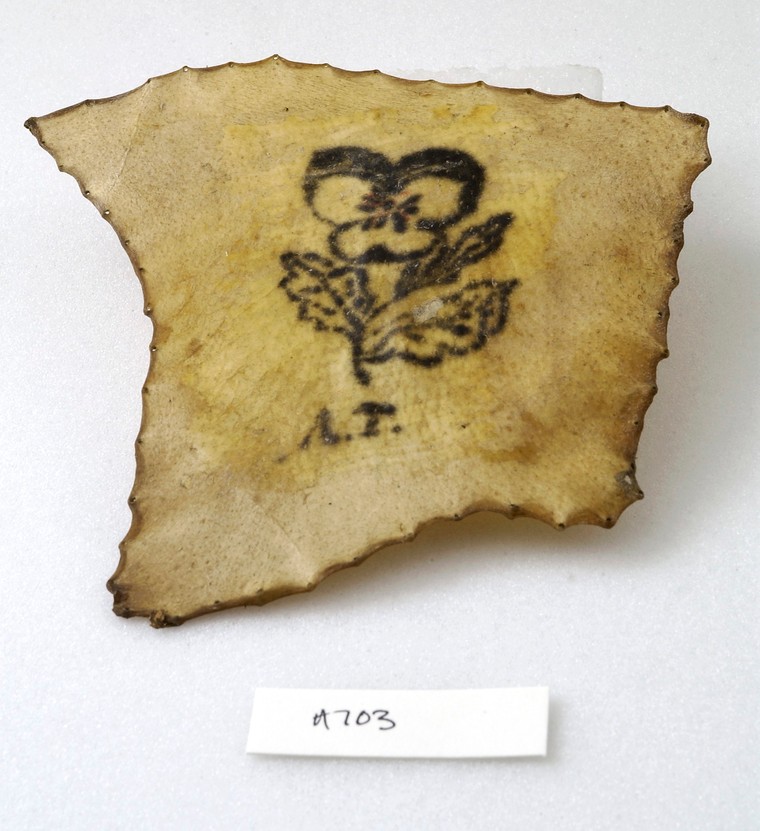

The Wellcome Collection in London has a range of tattoo examples in its collection, with over 300 tattoo fragments. Amsterdam Tattoo Museum sadly closed its doors some years ago, although tattoo enthusiasts can still visit the tattoo parlor. Also in the online world, there is a treasure trove of information at The Vanishing Tattoo, Triangle Tattoo, and The Tattoo Archive.

On a more gruesome note, how about the idea of viewing preserved tattoos? The ethics of collecting skin from cadavers is naturally controversial. However, just like an animal pelt, inked skin can be preserved in chemicals after death. The poor Painted Prince is probably the first example of this, enslaved even in death. More recently though, the National Museum of Australia asked if retired school teacher Geoff Ostling would donate his heavily tattooed body to them after death, for posthumous display in their collection.

Irish performance artist Sandra Ann Vita Minchin commissioned a tattooist to painstakingly recreate a 17th century painting by Jan Davidszoon de Heem across her back. De Heem was the most celebrated Dutch still-life painter of his day. She plans to have her skin preserved posthumously and auctioned to the highest bidder.

We can only guess at the original meanings of tattoos. Historians guess that they were about distinguishing your tribal connections and allegiances and may have marked transitions or initiations in the life of the community. They may have offered talismanic protection, or marked spectacular acts of valor. And, of course, they are art – now and always, a thing of beauty to adorn the body, reminders of our unique stories, inked onto our fragile yet resilient human skin.

For a fascinating insight into the meeting point between fine art and tattoos, listen to A Mortal Work of Art on the BBC.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!