Summary

- Since the 16th century, taxidermy has combined scientific curiosity with artistic imitation of nature

- From its very beginnings taxidermy was used for developing collections of rarities and natural curiosities, therefore it has always had an aesthetic function at least in part

- Contemporary takes on taxidermy in art vary a lot depending on the artist

- Damien Hirst, Maurizio Cattelan, Cai Guo-Qiang, and others – taking a closer look at some of the most interesting artists working in taxidermy

- Opinions on taxidermy in art today are still conflicting – what is the main criticism and recognition of the practice?

On the Edge of Life and Death

The word taxidermy comes from Ancient Greek, and it is a combination of two separate words: taxis (arrangement, disposition) and derma (skin). Taxidermy in its most complex and current meaning differs from the simple conservation of organic bodies but denotes the ability to reconstruct the forms and attitudes of living animals, starting from the body of a dead animal, after having carried out various treatments aimed at preserving it over time. We can, therefore, speak of both an artistic function of taxidermy, as it seeks to evoke a sense of aesthetic beauty through the imitation of nature, and a scientific function, as essential support for the study, collection, and conservation of bodies for a didactic purpose.

Taxidermy understood as an ornamental art or as a technique for study purposes dates back to over four centuries ago. The first documented collection was made in Holland in the first half of the 16th century: a nobleman had transported numerous specimens of birds by ship, but they died during the voyage. After numerous attempts to preserve their skins, the birds were emptied of their internal bodies and stuffed with various spices. In the end, the experiments were successful. Some specimens, mounted on pedestals, were preserved for a few years—even if, aesthetically, they were far off and rougher than the current preparations.

The thriving market of the East Indies and the New World, and the curiosity aroused by the arrival of exotic animals with the arrival of goods, stimulated wealthy traders and gentlemen to organize collections of exotic material to increase their collection.

Embalmed crocodile, before 1534, Our Lady of the Graces Church, Mantova, Italy.

It is precisely in this historical phase that the concept of the museum was born, which at the time was identified as a “Collection of precious objects, of peregrine rarities and curiosities of nature.” And this activity is well expressed in the definition of Wunderkammern, or Chambers of Wonders, explained in one of my older articles.

Typical of the ancient collections of the 16th and 17th centuries, these series of materials were kept in special rooms of private houses and constituted a bizarre and heterogeneous collection of rare and exotic pieces. However, the materials exhibited had more a function of decoration than a function of systematic collection of natural finds.

However, the taxidermic techniques of this period were not yet very advanced. The oldest mounted specimen still in existence (1702) is an African gray parrot that belonged to the Duchess of Richmond, currently exhibited in Westminster Abbey, London.

Duchess of Richmond’s Parrot, Westminster Abbey, London, UK. Westminster Abbey.

An improvement in the techniques took place in the mid-1700s, thanks also to the formulation of an arsenical ointment, subsequently modified and perfected, which allowed tanning and an unassailability by moths. This ointment, created by the pharmacist Jean Baptiste Becoer, was used until the 1960s, to be replaced by other tanning pastes based on borax, less dangerous for the user.

During this period, the naturalistic museum underwent a real maturation as a scientific institution, making a decisive contribution to the development of systematic zoology and comparative anatomy. However, it remains a place of culture, extraneous to the social function.

In the 19th century, the spread of fine taxidermy exploded, not only for scientific purposes but also for its application to the aesthetic taste of the time: it was the period in which the coffee tables were made from an elephant’s paw, cutlery with shaped handles from crustacean claws, candelabras from a base of ungulate legs. The taxidermists wanted to celebrate the beauty of nature, and their mission was to recreate and preserve nature in all its glory and perfection; they wanted the animals to look alive and alert—beautiful, despite the inevitable death that is involved in this art.

Ethical Taxidermy

Juliade Ville, Sorrow, 2012. Artist’s website.

Nowadays, instead of reproducing a perfect imitation of the animal, contemporary taxidermists create dreamlike creatures as beautiful as they are disturbing. Their eclectic creations reveal a more sensitive and emotional story than the traditional realist taxidermy elements you can see in natural history museums. Most of these artists are part of the new alternative taxidermy form of art called “Rogue taxidermy” or “Ethical taxidermy.”

Ultimately, each person’s understanding of and ability to appreciate taxidermy is deeply personal. Some people think it’s morbid, but it’s about coming to terms with death. What seems to link all the modern practitioners of this art together is an abiding respect for the cycle of life, a reverence for their craft, and a deep desire to honor animals. They strive to source the animals used in their work in the most humane and ethical ways possible and do not kill the animals they use. Their commitment to sustainability and sensitivity is a far cry from the Victorian era. They are breathing new life into a centuries-old discipline, pursuing it with joy, respect, humor, and heart.

Walter Potter

Walter Potter, the Victorian age’s best-known anthropomorphic taxidermist, opened a private museum in 1861 to showcase his creations; he’d taxidermied 10,000 animal specimens by the end of his life. His elaborate displays included scenarios like kittens drinking tea and playing croquet at a garden party, squirrels smoking cigars and playing poker, and rabbits studying in a classroom.

Kate Clark

Artist Kate Clark, whose sculptural work involves a great deal of taxidermy, has mastered the process of working with large animals. Her main body of work consists of huge, almost mythological, taxidermied animals, from antelope to zebras to coyotes, with human faces sculpted onto the bodies. She sources the animals’ skin from hide dealers, often looking specifically for those that have been damaged or “shelved,” meaning they can’t be used for traditional taxidermy. Clark’s work, which has been shown locally and internationally since 2008, has a broad cultural reach.

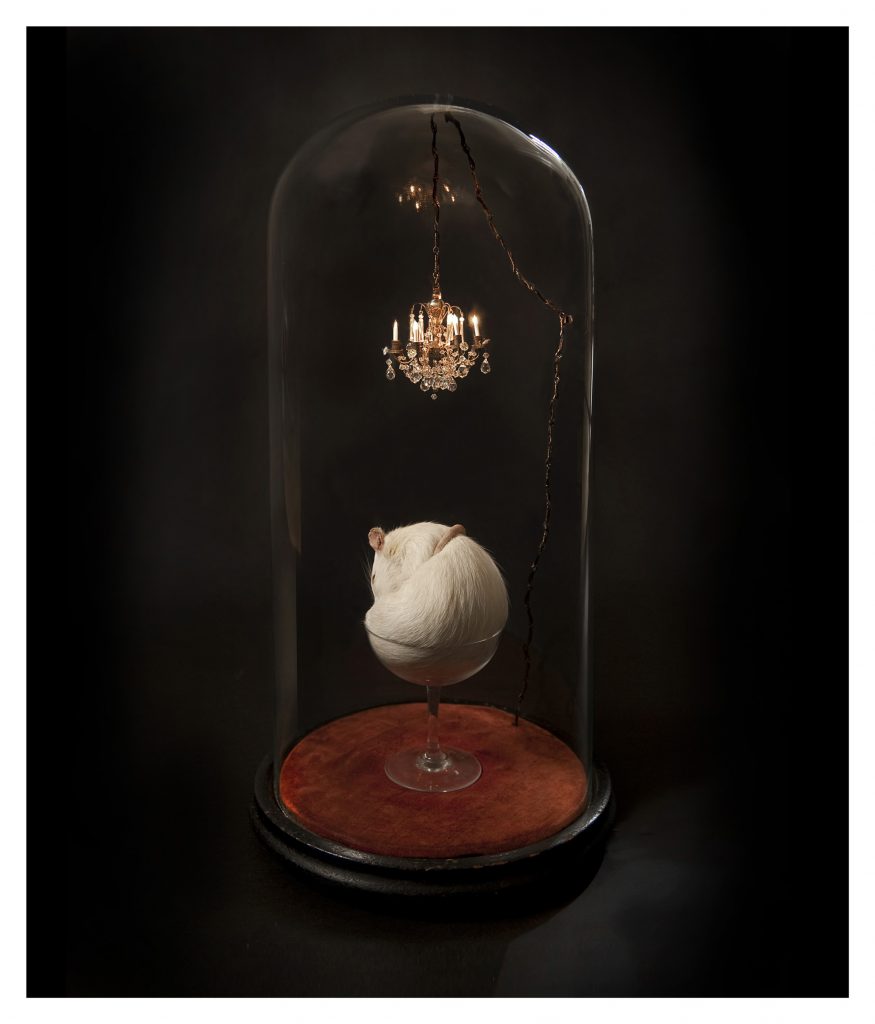

Polly Morgan

Self-taught with no formal education in art, Polly Morgan works with mediums of taxidermy, concrete, and polyurethane. She is interested in creating deceptions, with sculptural facsimiles made from painted casts and skin, as a way of exploring false narratives in our increasingly polarised and digitized society.

Morgan’s first pieces were commissioned by Bistrotheque, after which she was spotted by Banksy: a lovebird looking in a mirror; a squirrel holding a bell jar with a little fly perched inside on top of a sugar cube; a magpie with a jewel in its beak; and a couple of chicks standing on a miniature coffin. In 2005, he invited her to show her work for Santa’s Ghetto, an annual exhibition he organized near London’s Oxford Street.

Harriet Horton

Harriet Horton, An Aborted Beginning, 2015, Sleep Subjects series, The Crypt, London, UK. Artist’s website.

The largely self-taught practitioner, tired of the traditional presentation of taxidermy, Harriet Horton lends the ancient art a surreal and contemporary pop twist. Her approach to taxidermy has always set out to explore animals in a foreign environment from their original habitat. The use of dyes and lighting allows a playful narrative for a medium that sometimes holds a macabre association. It’s this juxtaposition of organic material with neon lighting that has become her signature style.

Sarina Brewer

Sarina Brewer, Capricorn, 2004. Artist’s webiste.

Sarina Brewer sees herself as an artist and naturalist who “recycles the natural into the unnatural, breathing new life into the animals she resurrects.” And what fabulous animals she creates: griffins from various eras, winged cats, vampire squirrels, and many more fantasy creatures that are a bit scary yet strangely fascinating.

Talking about her work, Brewer explains:

I deal with death, in what is considered by most, an unconventional manner. I do not view a dead animal as disgusting or offensive. I think that all creatures are beautiful in death as well as in life, beautiful on the outside as well as on the inside. I pay homage to them by reincarnating them in my work, creating a life where before there was only death.

Simone Preuss, Seven Bizarre Fantasy Taxidermy Artists, 2010, RecycleNation.

Pascal Bernier

With their bandaged paws, heads, and legs, Pascal Bernier’s creations immediately evoke pity from viewers. Only later do we realize that our sympathy is uncalled for, as the animals are long dead. But Bernier doesn’t let us off that easily. His series Accidents de Chasse or “Hunting Accidents” (1994-2000) points us to the unnecessary practice of hunting trophies.

Pascal Bernier, Jaguars, Accidents de chasse series, 1994-2000. Galerie Nardone.

Bernier explains the idea behind the series:

For time immemorial, one of the leading questions that humanity has asked itself is: ‘What’s to be done with the body?’ Hunting trophies, unlike mummies, are in no way a preparation for a journey into the afterlife. At best, they crystallize the glory of the hunter who imposes immobility on the living creature, reducing it to its image. At worst, they become decorative objects devoid of meaning. Only art will enable the animal (posthumously) to sell its skin for a high price.

Simone Preuss, Seven Bizarre Fantasy Taxidermy Artists, 2010, RecycleNation.

Claire Morgan

Claire Morgan’s work is inspired by the cycles of nature and the problematic relationships between humans and nature, as well as by personal experiences and memories of trauma. She started out working with temporary materials such as rotting fruit and other organic materials, but she is known mostly for her suspended installations combining jewelry and taxidermy.

Her practice has been focused on how humans understand and interact with the rest of the natural world, and their unwillingness to acknowledge their absolute lack of autonomy or control.

Maurizio Cattelan

I think there’s no necessity to make a special introduction to Maurizio Cattelan, but for those who never heard about Cattelan, he is an Italian artist known for his satirical sculptures and installations like America, Him, L.O.V.E., La Nona Ora, or the most recent one called Comedian.

Besides the controversial and shocking aspects found in his works, there’s always a strong message behind them. Many of his works, such as his taxidermy horses or pigeons, are based on simple subvert or puns clichéd conditions, and he used the animals in place of humans in sculptural tableaux. One of his most famous taxidermic works is Novecento – the title itself (Nine Hundred) is an Italian term for the 20th century as well as the name of Bernardo Bertolucci’s film from 1976 tracing the rise of Italian fascism. Cattelan’s horse in this way may symbolize a country exhausted by a century of upheaval and violence.

Maurizio Cattelan, Novecento, 1997. Google Arts and Culture.

Julia DeVille

Julia DeVille is an artist, jeweller, and taxidermist who only uses subjects in her taxidermy that have died of natural causes. She is an advocate for animal rights and began including taxidermy in her artwork in 2002, combining it with her jewelry-making practice to produce small sculptures and installations.

Her taxidermy creations seem to have sprung to life from fairy tales. There’s the clever raven, the enchanted deer, the lucky goose, and many others. Only, they’re not alive, merely frozen in time. Talking about her choice of topic, DeVille explains:

I am fascinated with the aesthetic used to communicate mortality in the memento mori period of the 15th to 18th centuries, as well as the methods the Victorians used to sentimentalize death with adornment.

Simone Preuss, Seven Bizarre Fantasy Taxidermy Artists, 2010, RecycleNation.

Damien Hirst

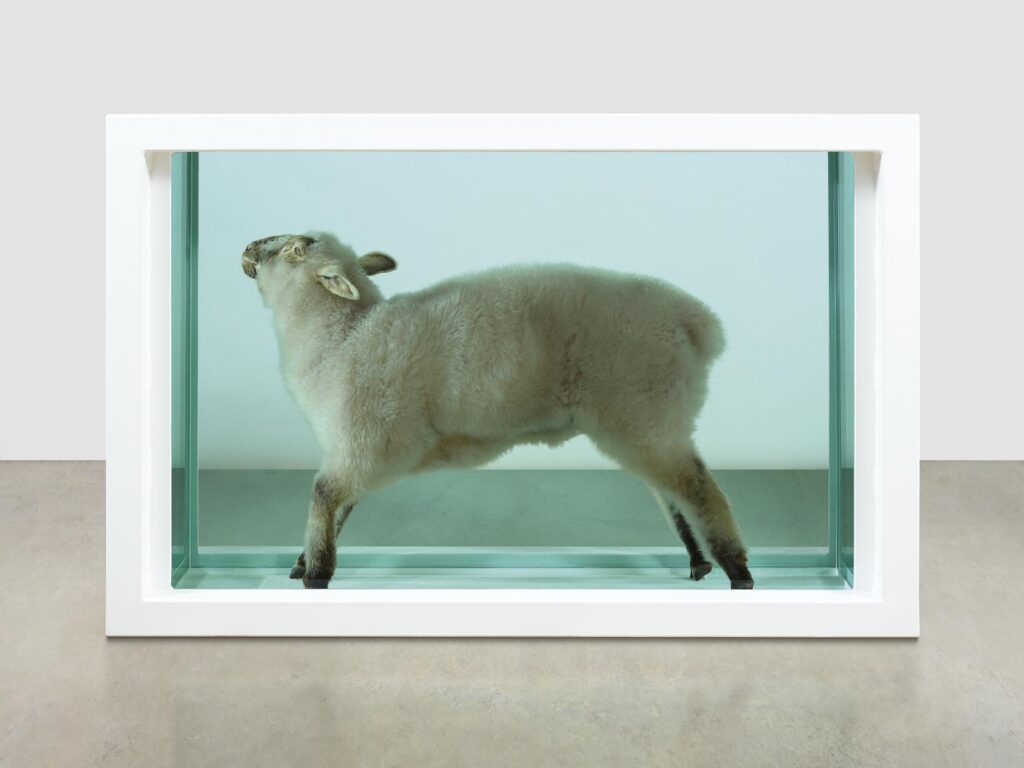

The David Winton Bell Gallery at Brown University hosted an exhibition called Dead Animals, or the curious occurrence of taxidermy in contemporary art which surveyed the use of taxidermy through the work of 18 contemporary artists among which appeared also Damien Hirst. Included in the show was Hirst’s work Away from the Flock – a lamb in a tank of formaldehyde solution – which is a key early work in Hirst’s Natural History series.

The title came after Hirst completed the work and observed the tragic beauty of the animal. The lamb, identifiable within Christian iconography as Jesus, has been separated by death from the living.

It’s just that … failure of trying so hard to do something that you destroy the thing that you’re trying to preserve.

Elizabeth Manchester, Damien Hirst, Away from the Flock, 2009, Tate.

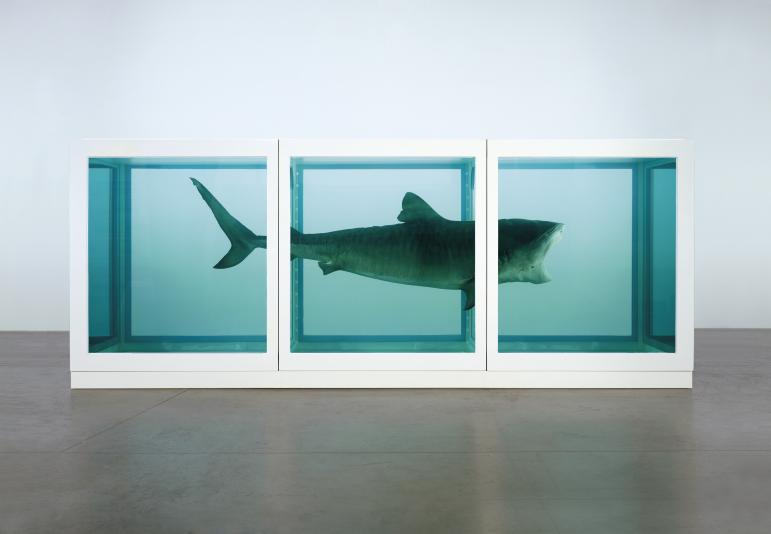

Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991. Artist’s website.

The inconspicuous but powerful formaldehyde solution in which Hirst enclosed his animals is predestined to convert ephemeral corpses into more resistant forms. Another of his taxidermy works is the famous shark (The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living) whose story you can read here. Hirst’s methods of preservation, though, do not stop the deterioration, they slow it down to a point where it is hardly detectable. The shark and the many other taxidermy works of Hirst’s Natural History series – are kept in a zombie-like undead state of abeyance, presenting the physical results of death.

Cai Guo Qiang

Cai Guo Qiang, Heritage, 2013. The Guardian.

Captured above, this impossibly theatrical and spectacular artwork depicts a scene that could actually never occur in nature, 99 animals – including a whole tiger family – drinking side-by-side from a still blue watering hole.

This dramatic piece, by Chinese artist Cai Guo Qiang is realized in faux-taxidermy: each animal is carved from polystyrene and cloaked in appropriately dyed goat hide. Recalling the impossible “paradise paintings” by 17th Flemish artist Jan Brueghel the Elder – biblical visions in which species representative of all four corners of the earth coexist in harmony – Cai’s contemporary interpretation has a more ominous insinuation.

The dreamlike stillness is perturbed only by the sound of water dripping from the ceiling: a reminder of time’s passing and of the rapid dwindling of resources that threatens the animals that have gathered to drink around what might be the last remaining oasis. With undertones of religious art history woven through its topical focus on environmental degradation, Heritage invokes a final prayer for what might be the very end of animal life on this planet.

Les Deux Garçons

Les Deux Garçons is a collective name of Michel Vanderheijden van Tinteren and Roel Moonen, a Dutch artist duo using taxidermy as a big part of their creative oeuvre, yet in a less traditional way than you might expect.

The duo started working together in 2000 and have since then created a name for themselves with absurd, theatrical sculptures. They are well-known for their controversial taxidermy pieces: instead of giving the dead animals back their natural appearance, they transform them into fantastic creatures. Siamese twin-lambs, parakeets that are half-animal, half-porcelain figurine or exotic birds trapped into intricate compositions of delicate cups and saucers.

Even though humor certainly plays a role in their work, sometimes even morbid humor, their work also incites reflection.

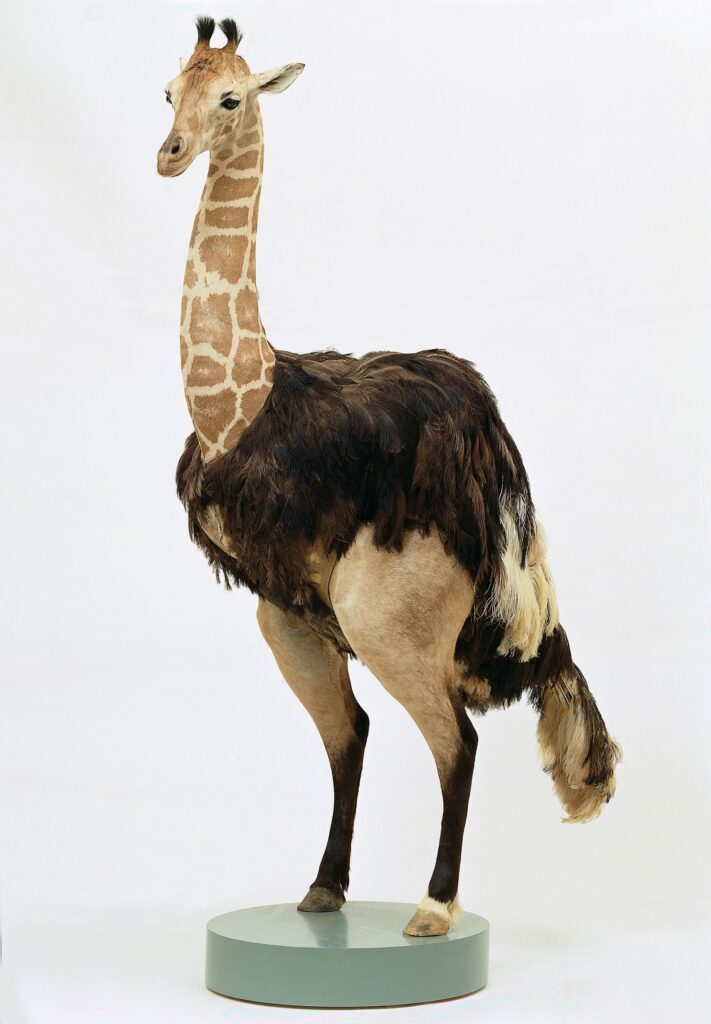

Thomas Grünfeld

Thomas Grünfeld, Misfit (penguin/peacock), 2005, Newlyn Art Gallery, Newlyn, UK. Gallery’s website.

Thomas Grünfeld is a contemporary German sculptor best known for his Misfits series of hybridized taxidermied animals. Grünefeld’s animals, however, subvert the typically scientific nature of taxidermy and instead represent fictional creatures. About this series, the artist has explained:

Using the collage principle, I designed new species, which makes it possible, for instance, to unify enemies in nature in one body.

The works reference also German folklore, specifically children’s wolperfinger – moralizing fables about human-like animals – and as such evoke proverbial battles between real and imaginary, good and evil.

Angela Singer

Angela Singer is an artist and animal rights activist of British and New Zealand nationality. Since the mid-1990s, Singer’s art has explored the human and non-human animal relationship, driven by her concern with the ethical and epistemological consequences of humans using non-human life, and the role that humans play in the exploitation and destruction of animals and our environment.

She sculpts in various media including modeling clay, wax, fiber, ceramics, gemstones, and vintage jewelry, as well as wool and silk. Many of her sculptural works combine mixed media with vintage taxidermy. Singer is known for working with vintage hunting trophy taxidermy that natural history museums have thrown away and which she recycles into new sculptural forms to explore the human/animal divide. She calls this practice “de-taxidermy”, a process that involves revealing the wounds inflicted on the animal, wounds that are obscured by the taxidermy process, and its attempted rescue from time.

Angela Singer, Nepenthe, 2011-2015. Artist’s webiste. Detail.

A Mirror to Investigate Ourselves

Les Deux Garçons, Oval. Artists’ website.

Taxidermy is in fact already a complete art form in itself, so the addition of the word “artistic” only serves to reiterate that there is a variation as compared to the naturalistic preparation. In recent years, this form of artistic expression has once again taken hold. The productions in this field are very different from each other, and they are the most disparate and extravagant. They range from the creation of costume jewelry objects, furnishing accessories, little animals dressed as dolls, chimeras, and much more to form what is now called Rogue Taxidermy, to get to the status of real works of art with high contents and levels of communication.

Opinions regarding this art form are diverse and conflicting. Much criticism is strongly opposed because it is believed that it is not respectful towards animals to use their bodies or their skins for any purpose, much less for artistic purposes. Other comments and opinions are strongly in favor of this kind of art, finding these artistic productions interesting, fascinating, or culturally enriching.

Artistic Taxidermy, this particular branch of taxidermy, affects the collective imagination. More than a message, however, it is an invitation to reflection, a continuous and multifaceted reworking of contemporaneity, an attempt to use these animal remains as a mirror to investigate ourselves and our society, composed of human beings and animals.