The Miniature Rooms of Narcissa Niblack Thorne

The Thorne miniature rooms are the brainchild of Narcissa Thorne, who crafted them between 1932 and 1940 on a 1:12 scale. Incredibly detailed and...

Maya M. Tola 9 January 2025

Over 100 years have passed since the October Revolution but this remarkable event still fascinates not only historians dealing with politics and society but also art historians. Let us take you for a little trip back to early Soviet Russia, but instead of looking at the great abstract paintings, avant-garde photography, or audacious architectural projects, let’s take a little sneak peek into Russian houses, their kitchens and living rooms. Here’s how the Russian avant-garde wanted to transform everyday life.

Russian Constructivist Avant-Garde wasn’t a solid monolith. One group of artists, among them Naum Gabo, concentrated on formal development itself. Another, numerous one, felt that it was not enough.

In 1921, Lenin introduced his New Economic Policy, which partially restored free market to centrally planned economy. The early communist state struggled with hyperinflation. What was the role of an artist in the time of unstable economy and heavy industrialization? Wasn’t pursuing formal innovation a bit bourgeois or even counter-revolutionary? That was the concern of many Russian avant-garde artists, among them Varvara Stepanova. In her paper On Constructivism, which she presented the same year in the Moscow Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk), she tried to deal with this issue. The lecture ended with a discussion among the artists. They decided it was a time to shift from autonomous art to “production.” After Stepanova’s lecture and Alexandr Rodchenko’s famous “last paintings” (three monochrome canvases painted with three basic colors: red, yellow, and blue) Productivism was born.

This doesn’t mean that they all gave up “pure” art entirely, but stepped “from the easel to the machine,” in the words of critic Nikolai Tarabukin. Many developments in industrial design resulted from this shift, spreading Constructivism outside Inkhuk, over the country, and leaking through the doors of Russian houses. It wasn’t all that easy, though. As political support for Russian avant-garde artists faded out with the new economic plan, Productivists designed more propagandist posters and book covers than everyday objects. Probably the most successful in the field of actual commodity production were Stepanova herself, hand in hand with Lyubov Popova and some other female artists, with their beautiful textile and fashion designs.

Furthermore, some of the artist were as much engineers as dreamers. Vladimir Tatlin designed a flying machine based on birds’ anatomy, that was supposed to be energy efficient and effective. It’s hard not to see the resemblance to Leonardo da Vinci’s design for a flying machine, based on a similar idea. Tatlin’s one was also beautiful, yet unsuccessful in flight.

Nikolai Suetin’s plate ware designs focused mainly on painted ornamentation, using abstract, geometrical forms, close to his own, as well as El Lissitzky‘s and Kazimir Malevich’s paintings. Many of his designs (with some notable exceptions) resembled earlier plate ware, only decorated in a different way.

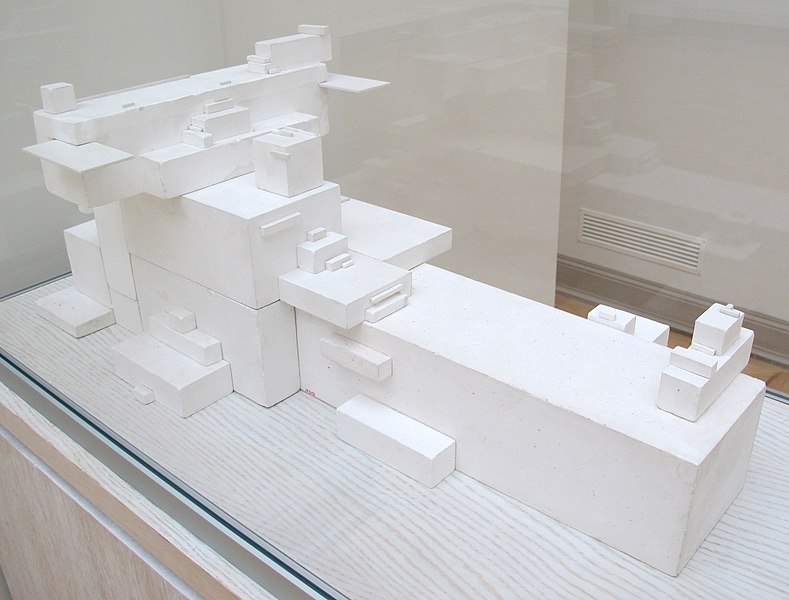

Malevich himself took quite a different approach to industrial design. Instead of ornamentation, he focused on the shape of an object. The result? A tea set that looks more like his sculptural Architectons than a regular tea set.

Before Constructivism fell out of favor and was replaced by Socialist Realism, some artist designed quite curious items, merging together abstract and realist motifs. In Mikhail Adamovich’s designs, rich colors, plain typeface, and compositional latitude coexist with realist depictions of Lenin, Trotsky, and work emblems like ears of wheat.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!