Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

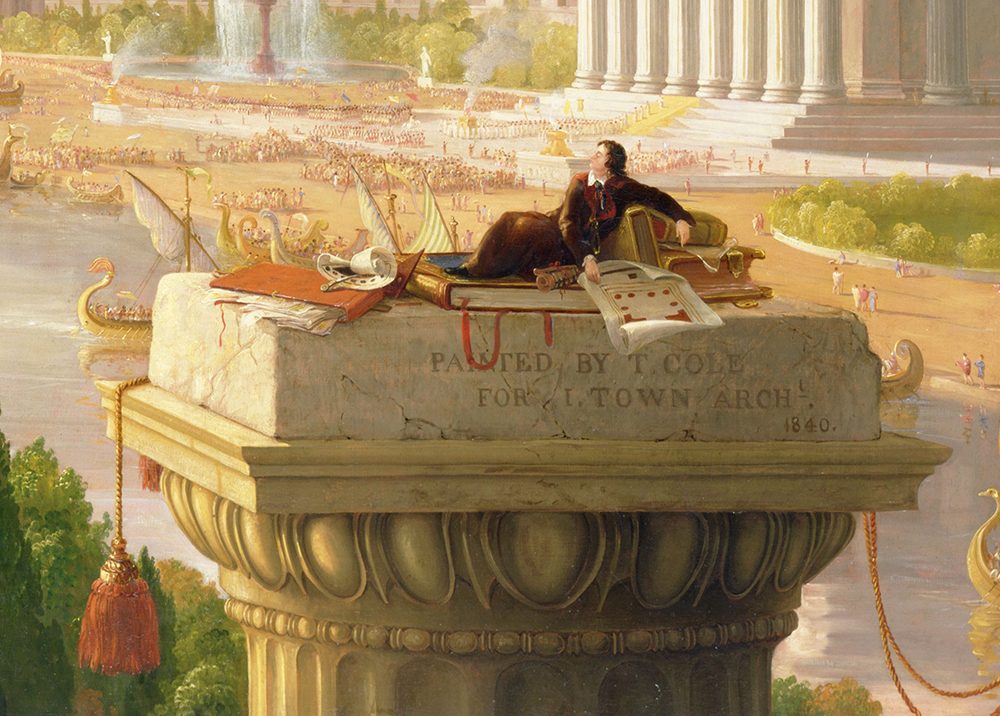

The Architect’s Dream was a favorite of mine when I used to teach the concepts of rhythm and harmony to my design students. Thomas Cole, the founder of the Hudson River School, created this work in 1840 for fellow American, Ithiel Town. Town was an influential architect who brought the Egyptian, Graeco-Roman, and Gothic styles back in vogue in America. Cole riffed on this, deftly combining these disparate styles—separated by centuries — into one precise, beautiful masterpiece of the architectural genre.

Cole paints out a timeline of architecture by placing the oldest style furthest back: the pyramid, obelisks, and an Egyptian temple. In the middle, at ground level, are two Greek temples of the Doric and Ionic orders, connected by a pilastered wall. On top of this Greek foundation are a Roman aqueduct and a circular Corinthian temple, signifying visually that the Romans built and improved upon older Greek methods. Across a body of water, in the forefront, is a Gothic cathedral. I associate all of the structures Cole chooses with spirituality in their respective cultures.

In the foreground, atop the huge column, is the reclining figure of Town surrounded by drafting tools, floor plans, and technical books. The inscription on the column indicates the identity of the artist and the client as well as the year of completion. The vast arch in which the scene is set is symbolic of looking through a window into Town’s mind.

Color, light, and proportion are expertly used to craft a surreal mood. Specific colors are assigned to each of the background, midground, and foreground, making it seem as if there are three separate worlds: the blue pyramid, distant as the sky; the temples, tan and bathed in the light of Classicism; and the Goth, brown and green, the depth of the colors alluding to the so-called “Dark Ages.” The three worlds are in such close proximity that it could only be a dream.

The lighting is dramatic, the light source not directly visible. It is only hinted at by the way light and shadow affect the scene. The yellowing sea and sky behind the cathedral, its orange windows, and the angle of the shadows in the midground suggest that there is a sunset there, hiding behind the cathedral. It is perhaps a metaphor for the spiritual enlightenment that can be found through religion. The sense of quiet mystery inside a cathedral; warm, glowing stained glass against cool dark stone — Cole brings it to the outside. This inversion of the exterior-interior makes the viewer linger just a little longer at the cathedral.

All the buildings are at an exaggerated scale and grow in size with distance. At the same time, they also strictly abide by a one-point perspective. At that distance, the pyramid should have been obscured from view behind the temples, yet it looms gigantic. It almost hangs cloud-like in the sky. The midground is dotted by people who are as tiny as ants, whereas Town is depicted as larger-than-life. This technique of proportioning figures according to their importance was a feature of medieval Gothic art and is fitting here because Town is positioned in the “Gothic world.”

Although from different architectural eras, the structures mesh together well because Cole stresses the similarities between them. There is a rhythmic verticality everywhere, especially in the midground with its regularly spaced columns. Less obviously, triangular shapes and arches echo throughout the painting.

This painting ultimately failed to impress its would-be buyer, Town. Town had commissioned Cole to interpret the city of Athens as a landscape with elements of history and architecture. After all, this was what Cole was famous for. But he had never visited Athens. And so he dreamed up a fantastical world based on Town’s work. However, it did not fit Town’s vision and although he acknowledged it as a fine piece of art, he refused to purchase it. Cole never worked for Town again. The Architect’s Dream remained with Cole and his family until 1949, when it was acquired by the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo, OH. This is where you can see the painting today.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!