Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

9 December 2024 min Read

Marxist, nationalist, feminist – these are the words that describe not only the political convictions but also the artworks of Frida Kahlo. Although born as Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón outside of Mexico City in 1907, Kahlo eventually shortened her name and frequently told people that she was born in 1910. This was the year that widespread political unrest finally culminated in the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution.

After nine and a half years of conflict, the revolution resulted in a dramatic shift in Mexican politics and culture. The ousting of the ruling elite paved the way for a new constitution, which in turn resulted in radical land reforms, equal pay laws for women, and the introduction of socialist currents to the country’s political landscape.

Growing up in the fervor of the revolution, Kahlo was deeply inspired by the resurgence of national pride and the spread of progressive ideas that followed. Her work Moses, painted as a reaction to Sigmund Freud’s book Moses and Monotheism, exemplifies many of these social and political attitudes.

The central focus of the mural is the symbolization of the female reproductive organs along with the sun and the rain as the universal givers of life. The top left corner is dedicated to Mexico’s Indigenous Aztec culture, which is placed on an even level with representations of ancient Egyptian civilization as well as the Greek, Hebrew, and Christian religions of classical antiquity. Below the level of the gods is that of people whom Kahlo considered to be great historical figures: Stalin, Lenin, Marx, Gandhi, and Christ, among others. It is interesting to note the ironic inclusion of Hitler, whom the artist referred to as the “lost child,” within this group. Finally, the bottom level depicts a tumultuous representation of the masses as a symbol of human and societal evolution.

Apart from the Mexican Revolution, perhaps the greatest source of inspiration in Kahlo’s life was her lifelong partner Diego Rivera. The two artists married in 1929 and moved to the United States the following year. While her husband was busy painting a number of commissioned works, Kahlo grew increasingly homesick and unhappy over the course of their three-year stay. On a more political level, this period made her quite critical of the United States, which she viewed as the embodiment of exploitative industrialization and capitalism.

Her Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States illustrates a clear dichotomy between the two countries. The Mexican side is represented by colorful images of nature, history, and cultural heritage, whereas a landscape of dull grey factories and pollution is used to represent the United States. While the flag in Kahlo’s left hand makes it clear where the artist’s loyalties lie, it is important to note the electricity generator that supplies power to the pedestal that reads “Carmen Rivera painted her portrait in the year 1932.” Equally important is the fact that the same generator is parasitically attached to the roots of the plants on the other side of the border, an allusion to the exploitative nature of the United States’ relationship with its southern neighbors.

Although one of Rivera’s commissions was to paint Man at the Crossroads, a mural in praise of industrial advancement for the Rockefeller Center, Kahlo expressed her views on the topic in a much different way. My Dress Hangs There takes the form of a disorderly collage of commercial advertisements, celebrity culture, and social unrest against the backdrop of a concrete jungle where modern skyscrapers mix with kitschy Greek structures and a medieval church. In effect, it appears that the only authentic item in this chaotic scene is the artist’s traditional Tehuana dress, the focal point of the work.

Despite being a high-ranking member of the Mexican Communist Party for several years before his tour of the United States, an ideological dispute with other members of the central committee ultimately led to Rivera’s expulsion in 1929. In solidarity with her husband, Kahlo also left the pro-Stalinist party, and the couple’s political sympathies began to shift in support of the exiled Leon Trotsky over the next several years.

In 1937, they managed to persuade the leftist government of President Lázaro Cárdenas to grant Trotsky and his wife, Natalia Sedova, asylum in Mexico. They invited the couple to stay with them in La Casa Azul, Frida Kahlo’s family home. Nonetheless, Rivera’s discovery that Trotsky and Kahlo were having an affair, one of many infidelities that marked the couple’s troubled marriage, forced Trotsky to seek refuge elsewhere.

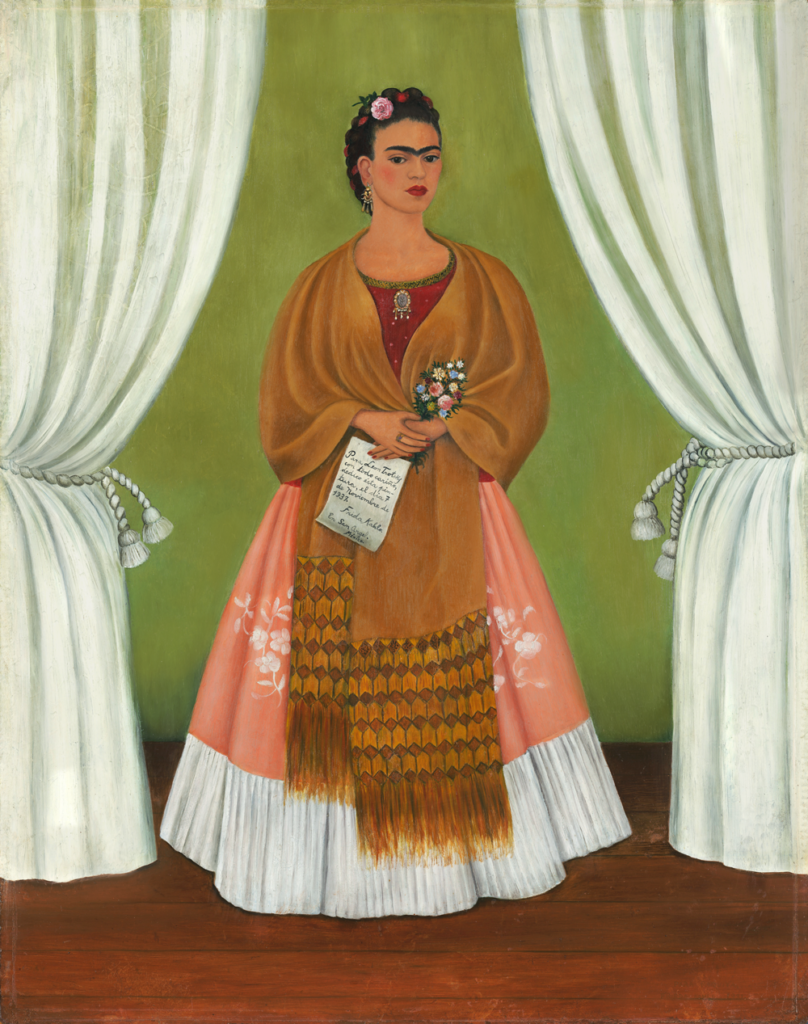

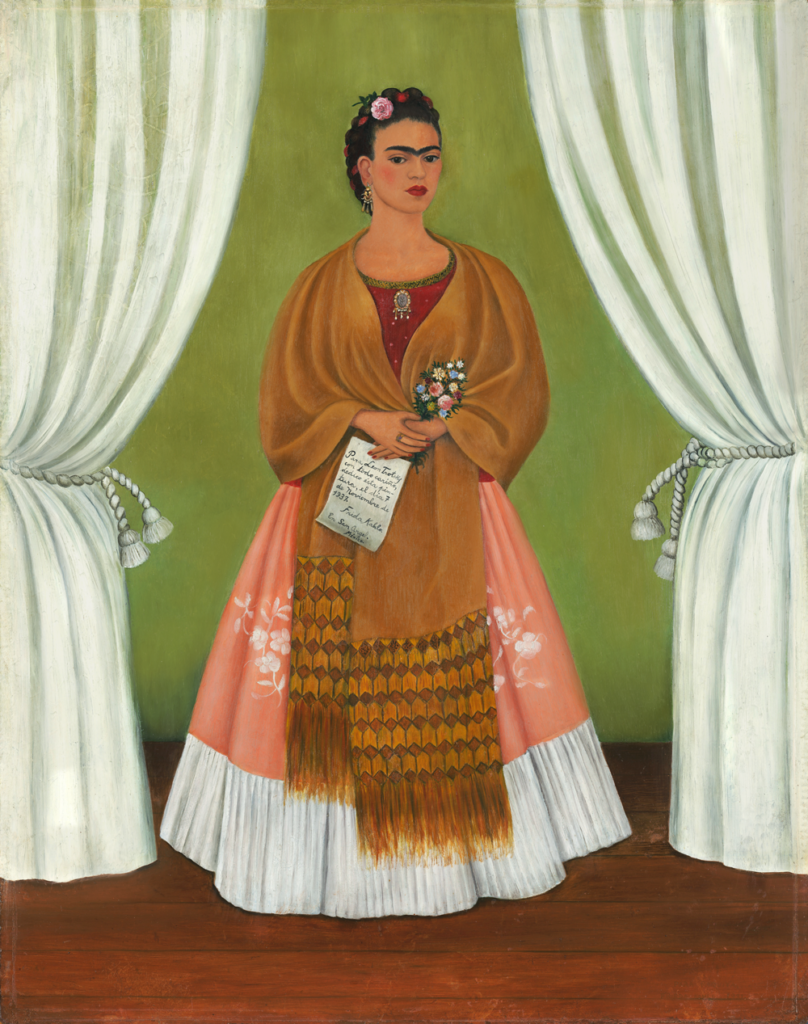

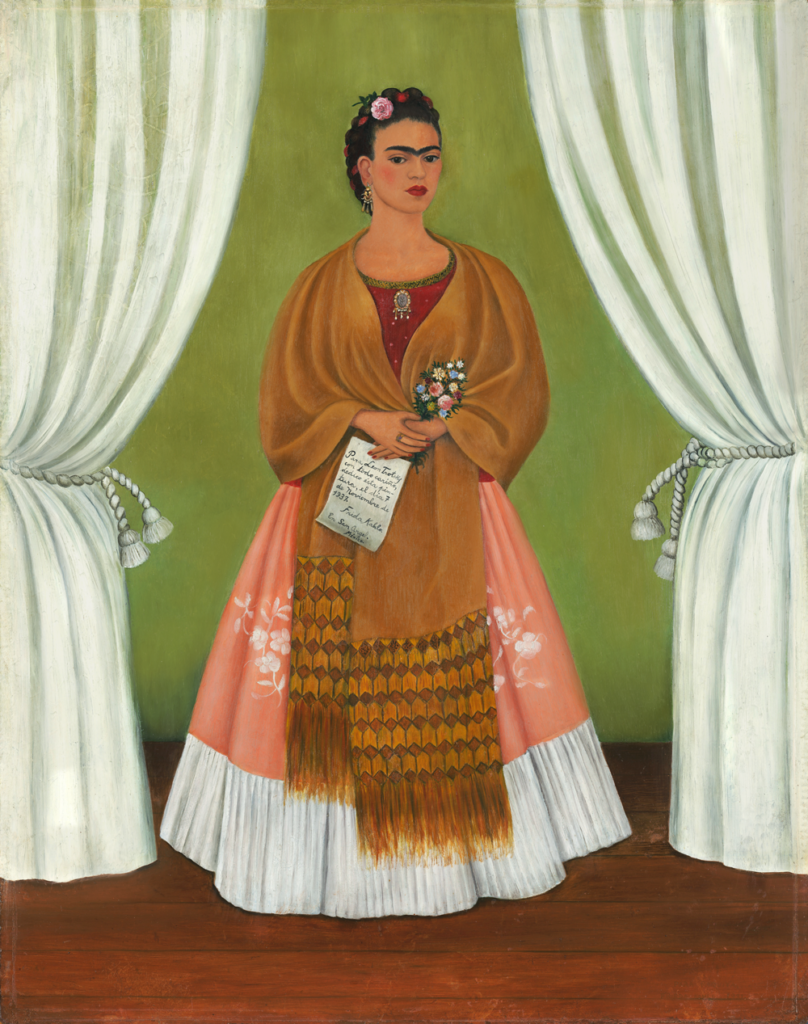

Upon moving out of Casa Azul, at the request of his wife, Trotsky left behind a self-portrait that Kahlo had painted for his 58th birthday. In the painting, Kahlo presents herself in a stately and seductive manner, holding a paper that reads “To Leon Trotsky, with all my love, I dedicate this painting on the 7th of November 1937. Frida Kahlo in San Ángel, Mexico.” The Russian couple eventually managed to find a residence not far from Casa Azul. However, in May 1940 a failed attempt on Trotsky’s life was carried out by the Soviet agent Iosif Grigulevich and the muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, who remained loyal to the Mexican Communist Party after Rivera’s departure. Nonetheless, the second attempt, this time executed by the Spanish agent Ramón Mercader in August of the same year, was successful. Leon Trotsky died in Mexico City on August 21st, 1940.

Despite the death of Trotsky and the ever-widening schism in the international communist movement, Kahlo remained dedicated to her revolutionary ideals for the rest of her life. In a way, Trotsky’s death demonstrated that Stalin was, in fact, the leader of the communist world, a reality that both Kahlo and Rivera had to accept in spite of their departure from the Party.

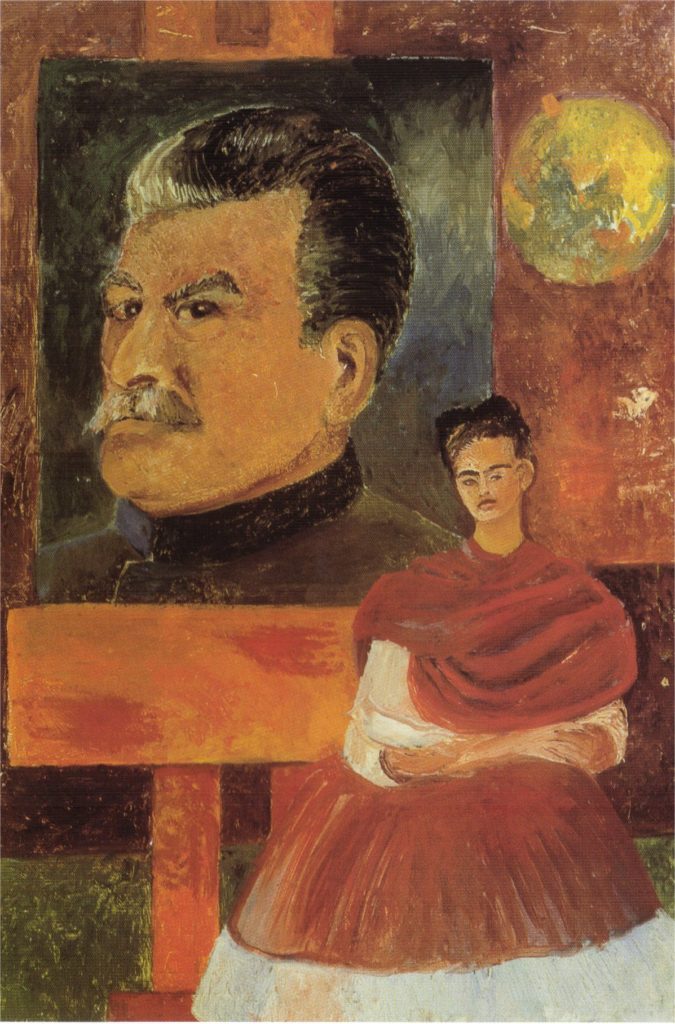

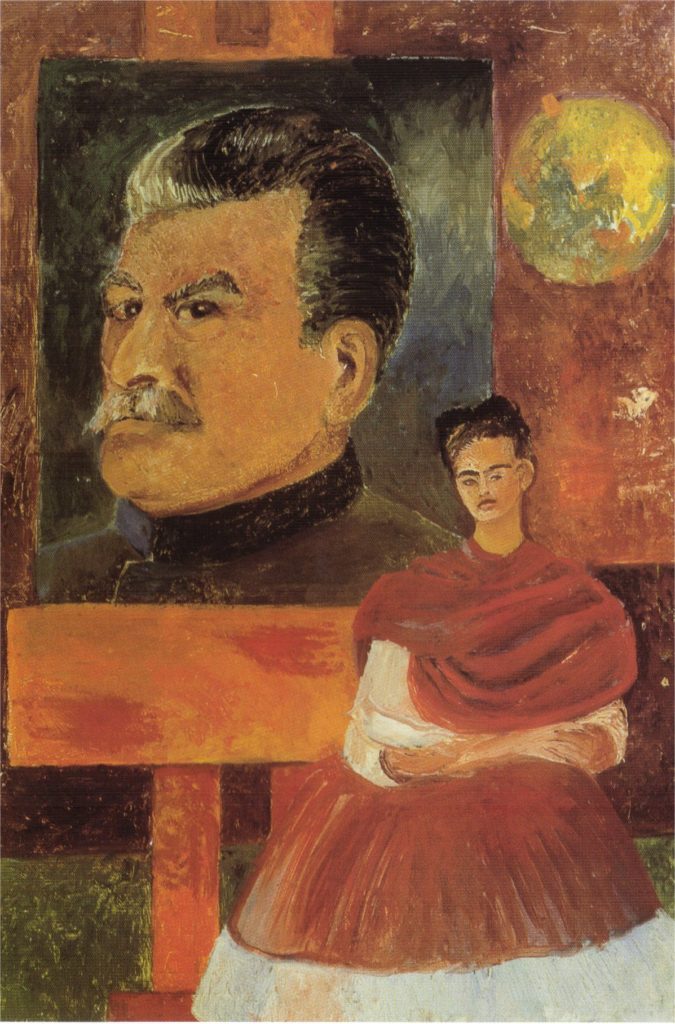

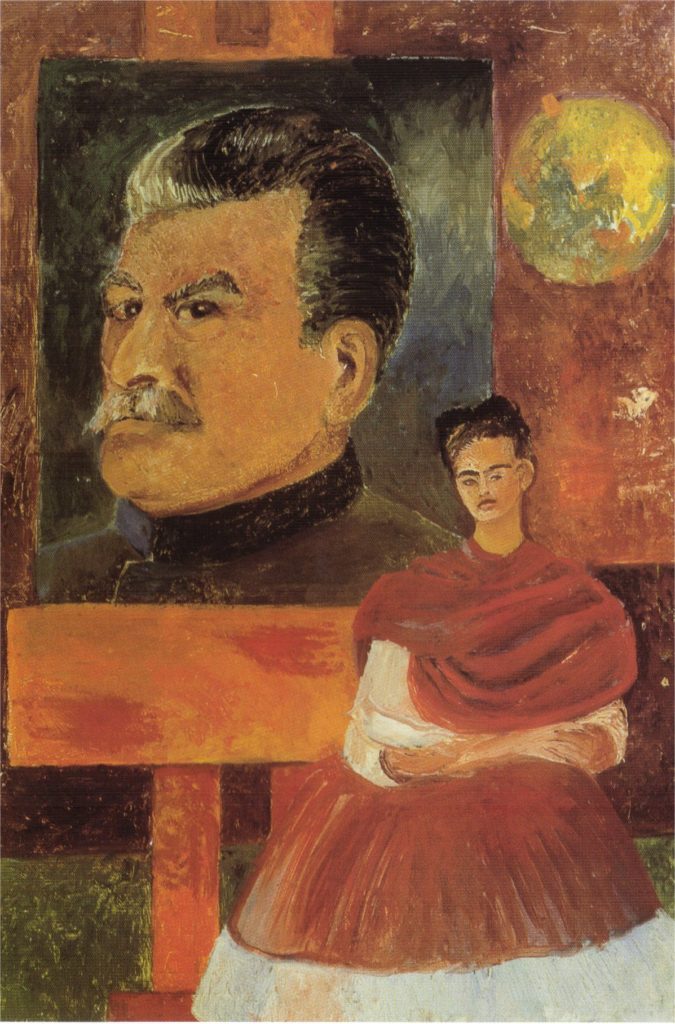

Following Stalin’s death in March 1953, Kahlo began work on a painting in his honor. Her self-portrait with the “Great Leader” elevates Stalin to a position of almost religious importance, a status he held throughout his thirty-year rule in the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, despite her reverence, Kahlo was unable to paint the portrait with the precision and clarity of her previous works, as severe pain from a bus accident in her youth and a lifetime of other health problems required her to take increasingly stronger medications that affected her artistic technique.

In her final days, Kahlo painted her last political work, Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick. Suffering from constant pain, declining health, and the impediments of heavy medications, Kahlo depicts Marx as a god-like being who is about to take her to heaven while at the same time punishing the unjust forces of capitalism and imperialism. Knowing that she is about to die, Kahlo strips her top to reveal the leather corset that had been supporting her broken back since the bus accident and drops her crutches to grasp not a Bible but a little red book – the Communist Manifesto.

Frida Kahlo died on July 13th, 1954 in Mexico City. The following day, a public procession accompanied her body, draped in a flag featuring the hammer and sickle, from the Palacio de Bellas Artes to the Panteón Civil de Dolores, where she was cremated. Indeed, her last wish was to be remembered as the stern and unshakable revolutionary whom Diego Rivera had painted at the center of The Arsenal a year before they got married, distributing arms to her countrymen in preparation for the next Mexican Revolution.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!