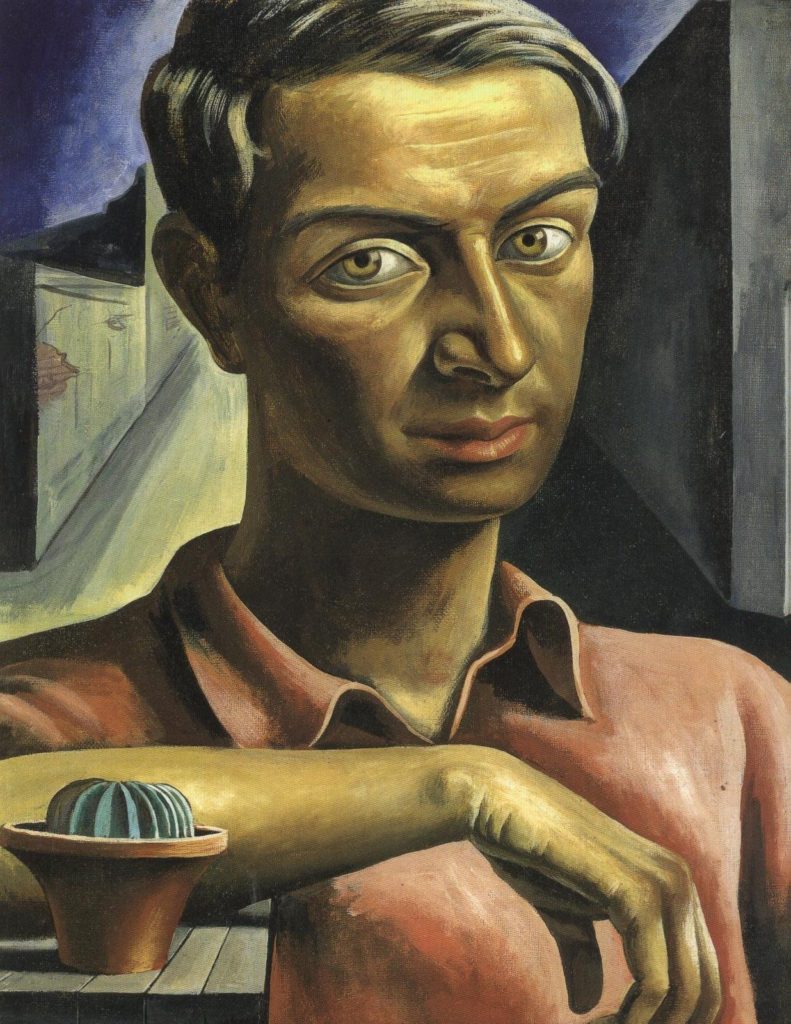

A Young Artist and the Birth of Nuevo Realismo

While Che Guevara may have been the most famous revolutionary to be born in Rosario, Argentina, the city was also the birthplace of Antonio Berni. Born in 1905, Berni demonstrated artistic talent from an early age, and his work was first exhibited when he was only 15 years old. In 1925, at the age of 20, he was granted a scholarship to study in Europe. Though he traveled extensively throughout Spain, Berni finally settled in Paris, where his studies of the emerging surrealist style of painting were supplemented by explorations of Marxist thought.

Although his sympathies for Marxism would serve to inspire Berni for the rest of his life, his association with surrealism was short-lived. Upon returning to Argentina in the early 1930s, the artist established himself at the forefront of the nuevo realismo movement, the Latin American response to the social realism that was being developed in the United States at the time.

Art in the Infamous Decade

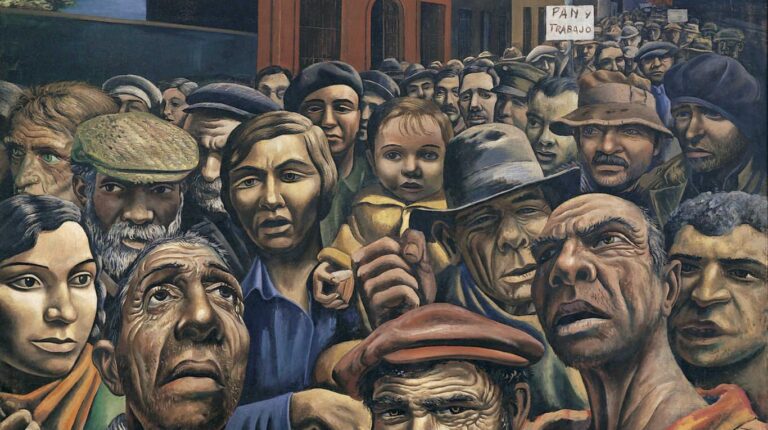

The September Revolution of 1930, in which the government of President Hipólito Yrigoyen was overthrown by a coalition of nationalist forces, marked the beginning of extensive social, economic, and political troubles in Argentina. Widespread corruption and instability during this period, which has come to be remembered as the Infamous Decade, was accompanied by a crisis of unemployment.

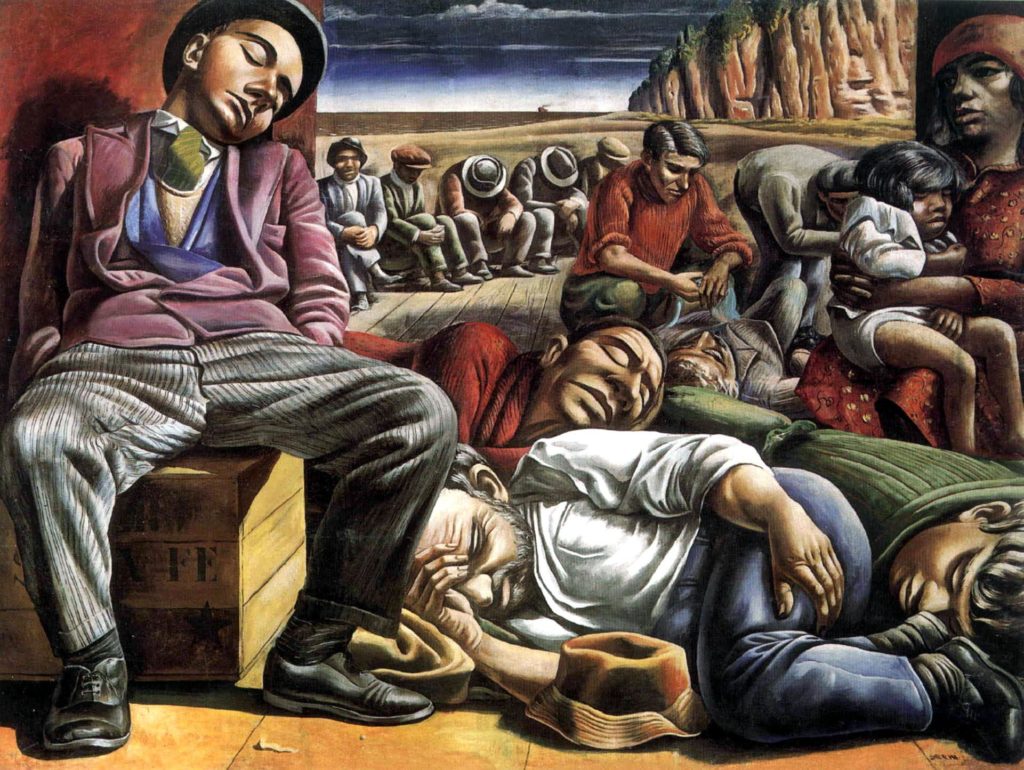

Berni’s Desocupados, painted in his iconic nuevo realista style, depicts a mass of destitute men lying around idly without work. At the right of the painting, an expressionless mother holding her sleeping child personifies the boredom and hopelessness of the situation. In many cases, popular unrest led to protests and demonstrations that frequently resulted in clashes with intervening police or military forces.

Such was the inspiration for Berni’s Medianoche en el Mundo. In this tragic scene, the artist evokes the image of Michelangelo’s Pietà, in which Mary mournfully holds the body of Jesus across her lap. Unfortunately, in this painting, the young man in the center and his two companions are not the only victims for the townspeople to mourn, as the road in the background is strewn with more bodies. What is important to note is that instead of revealing the name of the town where the massacre occurred, the title serves as a statement of solidarity with the victims of political violence around the world.

Juanito Laguna and Ramona Montiel

The Infamous Decade ended just as it began: with a military coup. In June 1943, the Argentine Army deposed the government of President Ramón Castillo, setting the stage for the election of Coronel Juan Perón for president in 1946. Perón ruled for nearly a decade, until his second term was cut short by yet another military coup in 1955. During this time, Antonio Berni traveled widely across Latin America and exhibited his works in Europe, particularly around the Eastern Bloc. Though still passionately committed to social issues, Berni had radically re-invented his style by the 1960s.

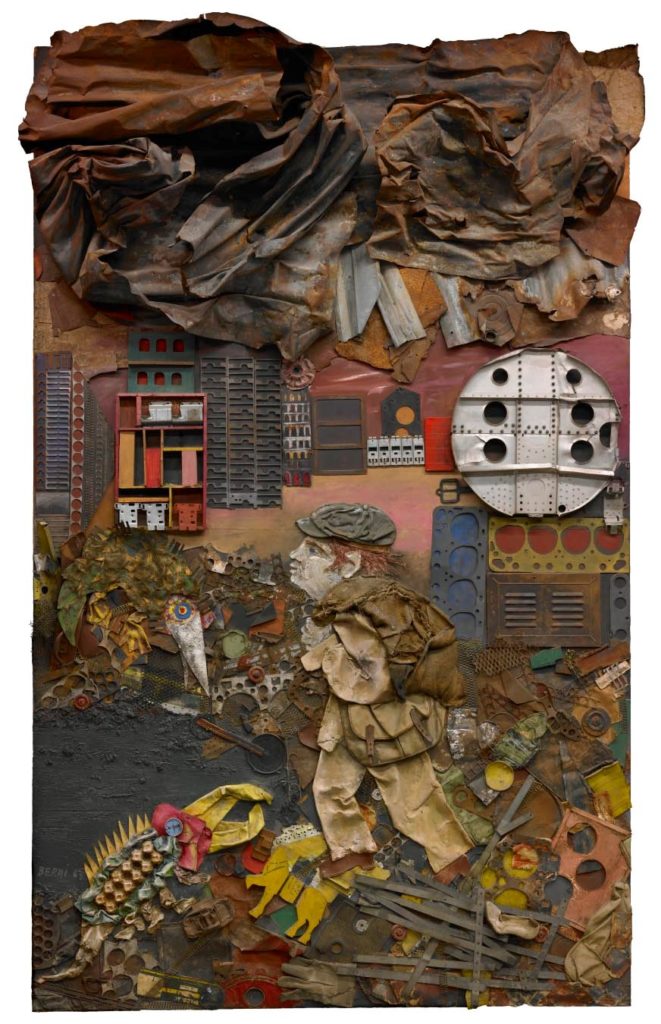

Much of his work from this period revolves around two characters: a young boy from the slums named Juanito Laguna and the prostitute Ramona Montiel. Like the rest of the series, El Mundo Prometido a Juanito Laguna is life-size in scale and made almost entirely out of authentic street junk. Here, the poor hero is depicted hiding amid garbage and grotesque strangers to escape the bombardment overhead.

In similar fashion, Juanito Va a la Ciudad shows the boy dressed in rags with a torn sack swung over his shoulder, marching through garbage to finally reach the dirty city streets that lie before him. When asked about the identity of his character, Berni stayed true to the message of solidarity he always tried to convey through his work, explaining that “Juanito Laguna is a boy from the outskirts of Buenos Aires or any Latin American capital”.

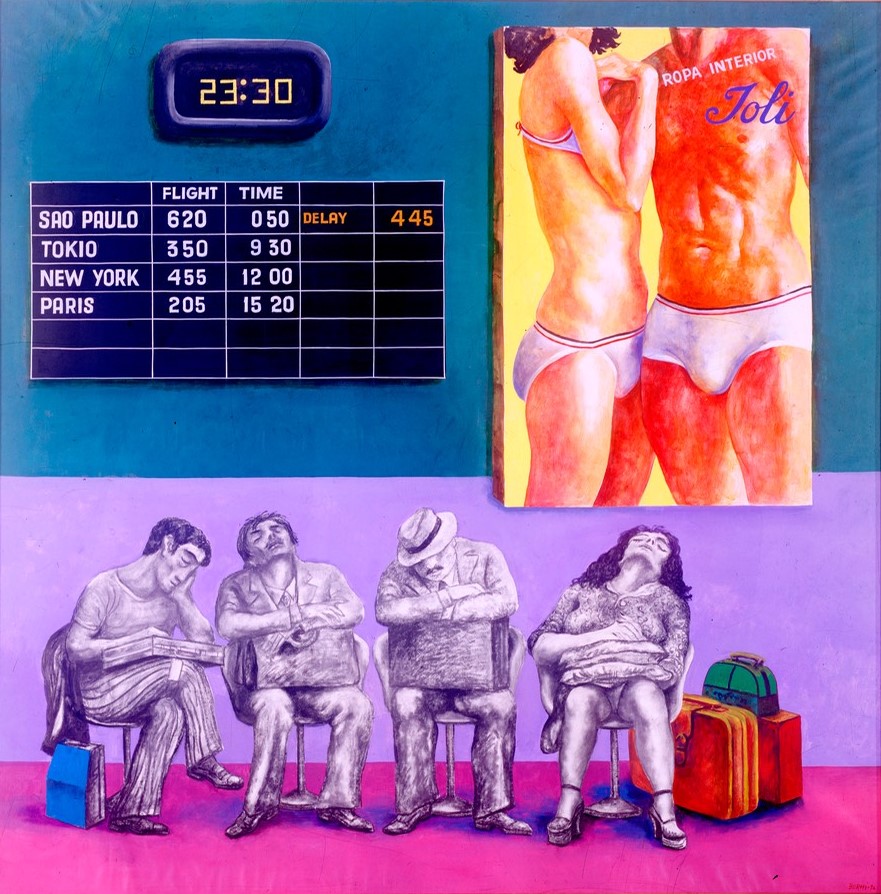

Like Juanito, Berni portrays the prostitute Ramona as a victim of chronic poverty and unemployment. In Ramona Espera, he presents her holding a basket with two other prostitutes on her left. Noteworthy details of this painting are the Pepsi-Cola cap above the doorway and the factory in the background. Both elements recur in other works from this series and emphasize the theme that rapid industrialization and globalization (or more specifically Americanization) are somehow tied to the social ills experienced by the likes of Juanito and Ramona.

Art During the Dirty War

For an Argentine artist primarily concerned with painting social issues, the late 1960s and 1970s provided ample material for inspiration. Perón returned from exile in 1973 and began a third term as president, which was cut short by his death the following year. His wife Isabel succeeded him but was deposed by the military in 1976. The return to military rule marked the beginning of the Dirty War, in which the junta attempted to purge the country of communists and left-wing dissidents. Antonio Berni, however, refused to stay silent.

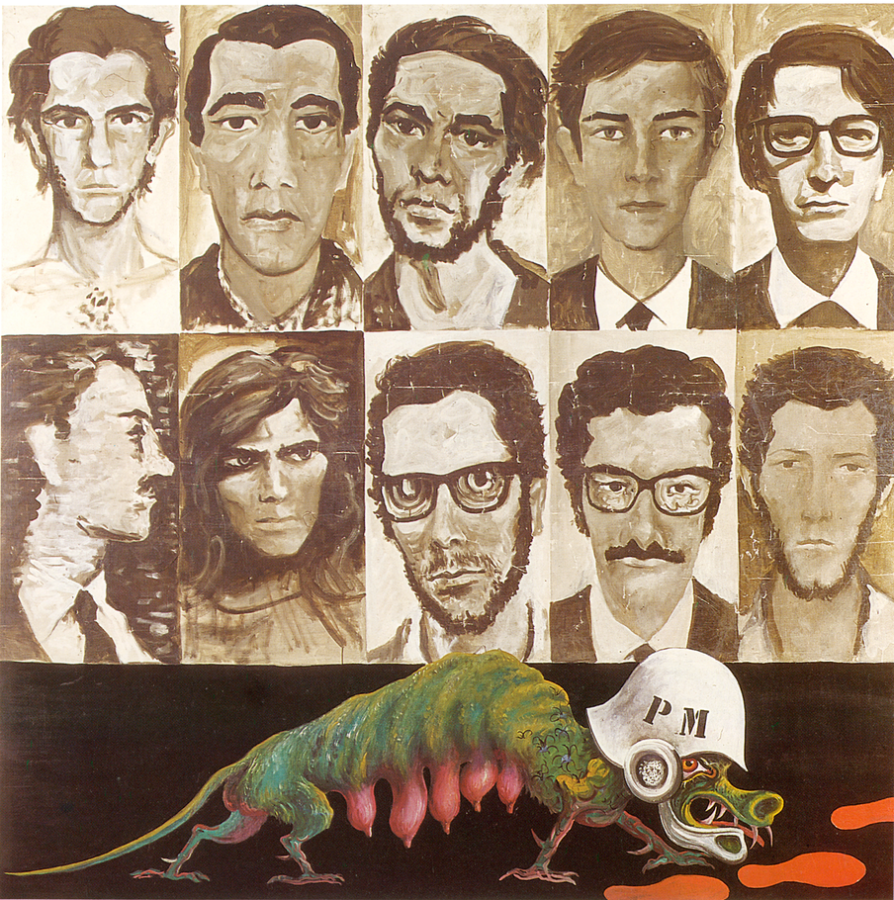

In 1969, the American ambassador to Brazil was kidnapped by revolutionary guerrillas in Rio de Janeiro. After three days, he was released in exchange for 15 political prisoners who had been arrested by the country’s military government. The 10 portraits portrayed in Los Rehenes are based on the photographs of some of those prisoners. The hideous monster guarding and torturing them wears the signature helmet of the policía militar.

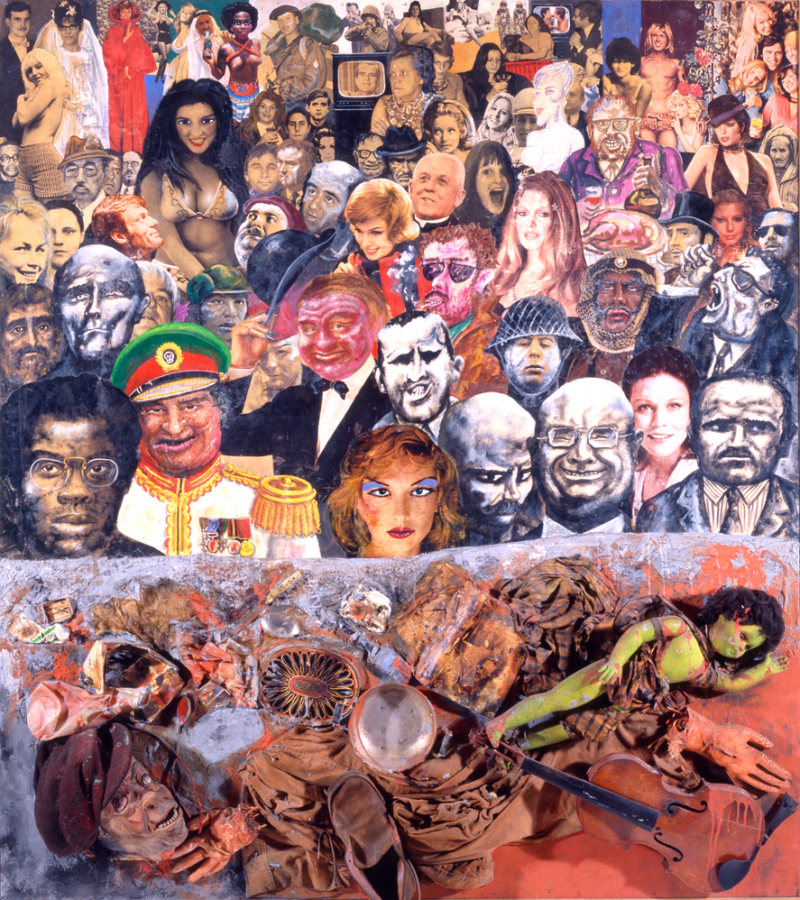

In the final years of his life, Berni became increasingly influenced by pop art. The chaotic collage of La Mayoría Silenciosa is reminiscent of the cut-and-paste style that was utilized by British pop artist Peter Blake to design the cover of the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Without forgetting to add a personal touch, Berni shows an international mob of celebrities, politicians, and other popular faces carelessly overlooking the junk that litters the world of Juanito and Ramona.

Berni’s Timeless Message

Antonio Berni died in Buenos Aires in 1981. The next year, Argentina went to war with Great Britain over possession of the Falkland Islands. Between 1981 and the collapse of the military junta in 1983, the country had five different presidents. Since then, Argentina has remained under stable democratic rule and its military actively participates in United Nations peacekeeping missions around the world. As a stark reminder of the country’s recent past, El Mundo Prometido a Juanito Laguna is now on display in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Buenos Aires.

Through his art, Berni showed that social problems are universal. Pathologies like violence and poverty are not unique to any single country or society. Moreover, in today’s increasingly interconnected world, social problems are becoming equally interconnected. Instead of ignoring the Juanitos and Ramonas of our world, we would do well to treat them with the respect and dignity that human beings deserve, lest one day we should find ourselves in their shoes. Instead of pretending that a far off war could never affect us or that a distant virus will never reach us, we would do well to show some solidarity with those “other” people, lest one day we should likewise find ourselves in their shoes.