Madness in Art: A Powerful Connection

Madness and art have long shared a profound and powerful connection, where the boundaries between genius and instability often blur. Many acclaimed...

Maya M. Tola 28 October 2024

As much as we wish otherwise, we all get sick sometimes. And though the pandemic seems to be in the past we still have to be cautious and thoughtful. If we look at it from a historical point of you, we will see that humankind went through a lot: plagues, epidemics, and diseases of any sort were thrown at us, and all the emotions we went through were always documented by artists. Sickness in art can be portrayed differently, as it is rather not an aesthetical subject, but there are quite a few depictions throughout centuries. They tell us a lot about the diseases of their time, or what passed for a disease, and also the approaches to recovery where it was possible. In the end, there is always a silver lining of hope for getting better, and today we are going to discover it together.

Jan Steen, The Sick Woman, ca. 1660, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands. Museum’s website.

Jan Steen (1626–1679) was a Leiden painter, a contemporary of Rembrandt van Rijn. But where Rembrandt often goes for serious and dramatic scenes, Steen favors humor. And it’s no different in this depiction of a sick woman. The lady dressed in a rich, shimmering dress confesses her love-sickness. It clearly must be very physically draining, if you take a look at her eyes. Suppressed desire led to a vague syndrome known as “hysteria”. Listening to her is an old woman. She listens with interest, a lewd smile on her face. But what is most interesting is the implement she’s holding, which is an enema syringe.

Interestingly, Steen was so adept at painting lively, chaotic lustful scenes that “A Jan Steen household”, meaning a messy scene, became a Dutch proverb (een huishouden van Jan Steen).

Gabriël Metsu, The Sick Child, ca 1663–1664, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Museum’s website.

In 1648, Jan Steen and Gabriël Metsu (1629–1667) founded the painters’ Guild of Saint Luke in Leiden. But as you can see, Metsu’s approach to portraying sickness is very different. He painted The Sick Child towards the end of his life, when his style resembled that of Pieter de Hooch or Johannes Vermeer, with bright light, weak shadows, and fresh even colors, but with thicker paint and coarser brushstrokes.

We see here a mother holding a sick child, not unlike a Pietà, or Mary holding Jesus. Her focus is solely on the child, but the child is looking beyond the frame as if demanding respite from suffering. On the side, we see a mug with a spoon. Clearly, the mother wanted to feed the child some porridge or soup, to strengthen it.

When you look at the large splashes of color, the painting becomes a wonderful interplay between the blue and red of the mother’s dress and the yellow of the child’s shirt. Lively colors are feeding off of the contrasts, but also amplify the unhealthy green pallor of the child’s skin. That is a perfect example how color can tell us about sickness in art.

Francesco Hayez, Portrait of Carolina Zucchi (The Sick Woman), ca. 1825, Galleria Civica di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Torino, Turin, Italy. Google Arts.

Francesco Hayez is considered a genius of historical Romanticism. He was also a very sensual man. In 1822, he started an intimate relationship with Carolina Zucchi, which possibly inspired a series of erotic drawings. Zucchi also posed for a number of his historical paintings. Their romance did not end well. Hayez married another woman and Zucchi fell ill.

In this portrait, we see Zucchi in her nightdress, her face lively, inquisitive, and inviting. Her dark eyes may have a bit of feverish gleam. But let’s be honest, we’d all like to look that well when we’re sick. Zucchi’s suffering may be coming from the expected heartbreak, which she is trying to prevent.

Christian Krohg, Sick Girl, 1880–1881, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway. Museum’s website.

Christian Krohg (1852–1925) was one of the great Norwegian painters of the Realist movement. In his works depicting members of the working class in Kristiania, he championed justice and freedom of expression. This dramatic portrait of a sick girl was possibly inspired by Krohg’s sister’s untimely death when he was young.

Just look at this girl’s eyes! She is defiant in the face of what most think is probably is the last stages of tuberculosis. Her body is small and weak against the massive pillow and the blanket threatening to swallow her. But there is strength in her face—an experience a child should never have, matured beyond her years, but not giving up.

John Bond Francisco, The Sick Child, 1893, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Museum’s website.

John Bond Francisco (1863–1931) was an American painter and violinist. Throughout his life, he pursued both of his talents. After spending a period of study time in Europe, he settled in Los Angeles. He became a major cultural figure, performing as a violinist, painting, teaching, and entertaining in his home and studio. Combining an art and music career, Francisco helped form the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra in 1897 and served as their first concertmaster.

In this painting, we see a reversal of the color play that we could observe in Metsu’s painting. Here, the pale green walls serve to offset the boy’s flushed face. He seems to be deeply asleep, but far from restful. We see medicine on the night table. And the woman minding his bed, knowing that sleep is often the best medicine, focuses on her knitting. As she’s using four needles it’s clearly not a simple project, but the focus may be helping her to banish the worry about the boy’s health at least for a few minutes.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1907, Tate, London, UK. Museum’s website.

Edward Munch was around disease since his early life. His father was a doctor, his mother died of tuberculosis when he was five, and his favorite sister succumbed to the same disease nine years later. Edvard himself was a sickly child. It is not surprising, then, that a topic of death and sickness would often come up in his art.

This is the fourth version of the theme that Munch came back to over a period of 40 years. Despite the energetic, almost cheerful colors, we sense the tragedy unfolding. The woman holding the hand of the child bent her head in utter despair. Even as the child tries to console her, we see that the loss will be heartbreaking.

Our friend Christian Krohg, who painted the defiant sick girl, was Munch’s teacher. Given that the men shared an experience of losing a sister early in life, it is possible they had conversations on the topic and the ways of portraying it.

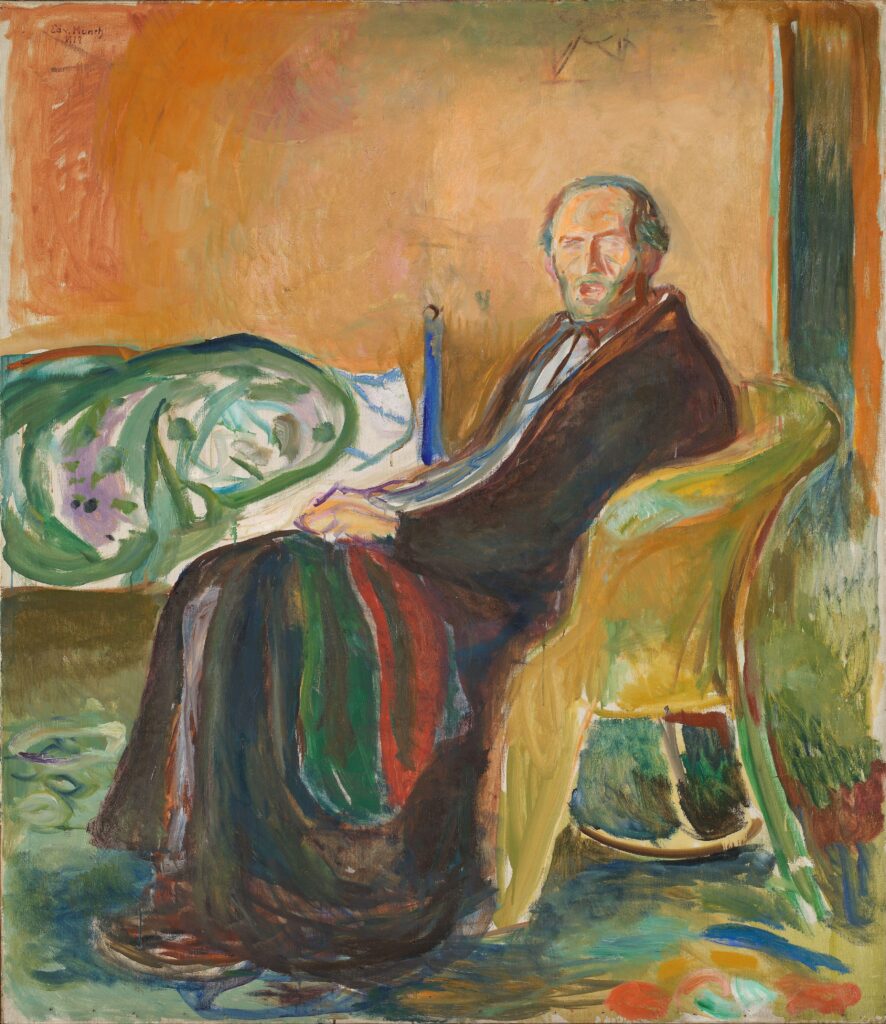

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway. Museum’s website.

The pandemic we went through is of course not the first one in the history of humanity. Europe went through multiple rounds of the Black Death, the bubonic plague. But as recently as the early 20th century, the Spanish Flu ravaged the world claiming anywhere between 20 to 100 million lives and infecting nearly a third of the world’s population over the course of two years.

While it is disputed whether Munch actually had the Spanish Flu, I still love the title of this painting. Self-portrait with the Spanish Flu, like a self-portrait with a lapdog, or a Lady with an Ermine. Munch focuses here on his own experience. One of recovery, because he is sitting in a chair, the unmade bed behind him, which means he feels strong enough to move. But his face is still marked by sharpened features, a testimony to the toll of the disease.

Spanish Flu is not often featured in art, and one of the reasons for it may be its proximity to the end of WWI, with war atrocities still occupying the minds of the creators more than, let’s face it, a less dramatic disease. Nonetheless, the Spanish Flu claimed the lives of artists as well, just to name Egon Schiele, Morton Schamberg, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Gustav Klimt.

Frida Kahlo, Henry Ford Hospital, 1932, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico, Mexico. Artist’s website.

Just like Munch, Frida Kahlo was no stranger to suffering and sickness, and it often found its way into her works. In 1932, she miscarried while in Detroit, and this painting channels her pain and despair. A small Frida laying in a huge hospital bed (does it speak to the sense of lack of control women experience during childbirth in a hospital, where everything is decided outside of them by the doctors?) is linked with umbilical cord-like ribbons to six items. The snail above her head refers to the slowness of the miscarriage. The fetus is a long-awaited son. The cast of the pelvic zone alludes to the fractures of Frida’s spinal column, but also the pregnancy. Below her is an autoclave used to sterilize medical equipment, alluding to Frida’s inability to carry the pregnancy to term. An orchid, a gift from Diego, but also a flower resembling the uterus. And there’s a pelvic bone, designed to shield and protect the uterus, but not fulfilling the task.

It is a scream of despair from a woman trying to make sense of the tragedy. Is it her fault, is it her body betraying her, will it keep on happening?

Carmen Lomas Garza, La Curandera, 1989, The Mexican Museum, San Francisco, CA, USA. © Carmen Lomas Garza.

Carmen Lomas Garza is an American artist of Mexican descent. She dedicates her creativity to the depiction of special and everyday events in the lives of Mexican Americans based on her memories and experiences in South Texas. Her works made their way into collections of many museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Here we see a sick woman looking with a trusting smile at La Curandera. Her son is playing at the foot of the bed. The Curandera reassuringly leans on the bed, swiping a handful of herbs over the women’s body. Curanderos are traditional native healers/shamans found in Latin America and the United States. They administer shamanistic and spiritistic remedies for mental, emotional, physical, and “spiritual” illnesses. The term curanderos can be traced back to the Spanish colonization of Latin America. Curanderos in this part of the world is the result of the mixture of traditional Indigenous medicinal practices and Catholic rituals. There was also an influence from African rituals brought to Latin America by slaves.

One thing I noticed as I did the research for this article is that sickness in art is a woman’s domain. Men are almost never portrayed as sick, they may be wounded, but not sick. It is also usually the women who care about the sick, with an odd exception of a male doctor (for if there is a doctor involved it will always be a man).

Another thing worth mentioning is that there is an art to being sick. It is always important to be mindful of people in our surroundings. And now, more than ever, we must remember to always take care of each other.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!