Madness in Art: A Powerful Connection

Madness and art have long shared a profound and powerful connection, where the boundaries between genius and instability often blur. Many acclaimed...

Maya M. Tola 28 October 2024

Throughout art history, domestic life has been a fundamental source of inspiration for artists. Whether it be lavish interiors or simplistic homely acts, artworks have repeatedly visualized domesticity as a worthy subject. ‘There is nothing like staying at home for real comfort’ – Jane Austen was supposed to say and some artists seem to share this thought.

While most European art was historically centered around religion, the 17th century saw artists begin to move towards domestic scenes that were absent of Christian idols. As genre painting, which depicted everyday activities and people, became an esteemed art form, various other movements would go on to champion scenes of the everyday life. Whether it is the beauty, drama, or relatability of home, we highlight works that prove home is where the art is.

Nicolaes Maes is a fitting example of a 17th-century artist who moved away from depicting biblical imagery in favor of genre painting. Taught by Rembrandt, Maes would later go on to develop his own individual style and subject matter. In turn, the likes of Johannes Vermeer and other contemporaries would go on to further refine these techniques that have now become synonymous with the genre.

Maes relished in the ordinary Dutch households of the time, portraying them with physical depth as well as plenty of room for drama. In his well-known series of Eavesdropper paintings, he creates scenes which invite viewer participation. With a mischievous woman looking directly at them, they join the game of eavesdropping on a private conversation in the next room. Listening to a tense exchange, the woman raises her index finger to her lips, urging the viewer to remain quiet. Meanwhile, other members of the household continue to dine upstairs. Left to consider what the secret conversation was about, the domestic setting becomes a place full of intrigue.

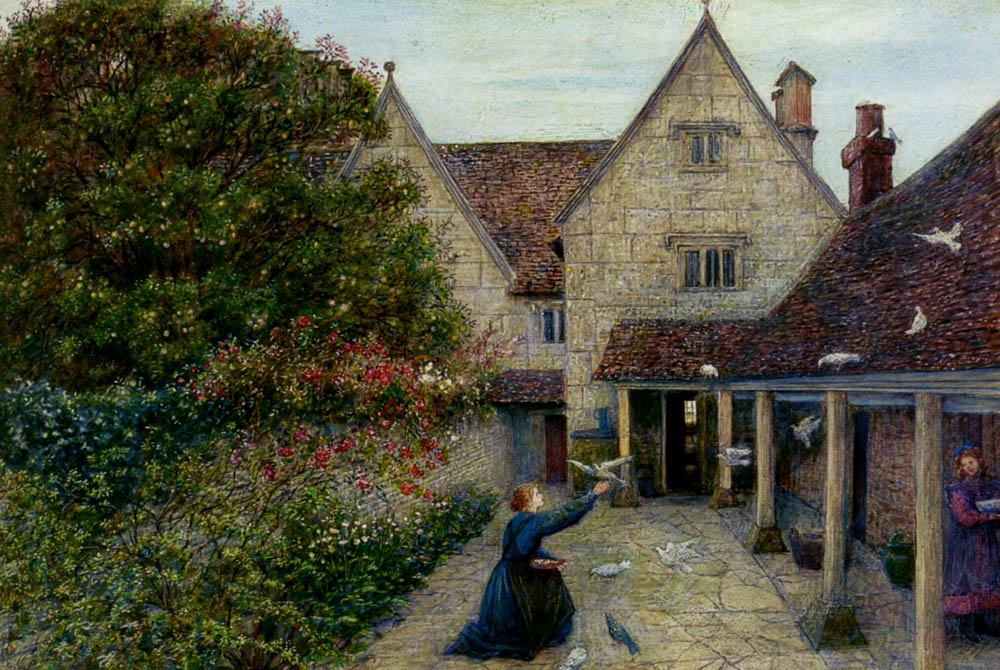

Marie Spartali Stillman was a Pre-Raphaelite artist and muse. She was also a successful model for the likes of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones. Despite being most renowned as the subject of many iconic works, Spartali Stillman was a successful artist in her own right. A pupil of Ford Madox Brown, she often re-imagined the classics and Italian landscapes in her watercolor paintings.

I stayed at Kelmscott for ten days and felt quite shut out of the busy world in that beautiful walled garden. I made two watercolors of the house and garden. One cannot imagine any place as quiet. Nothing ever seems to happen (…) things have been at a standstill for 300 years probably. It does one so much good to have this complete rest.

Marie Spartali Stillman, as quoted in: Margaretta S. Frederick, Jan Marsh, Poetry in Beauty: The Pre-Raphaelite Art of Marie Spartali Stillman, Wilmington: Delaware Art Museum, 2015.

With a Pre-Raphaelite closeness to nature, Spartali Stillman would often visit Kelmscott Manor (William and Jane Morris’ home in the English countryside) and seize inspiration to paint. Hence Spartali Stillman depicted Kelmscott Manor multiple times throughout her life. Valuing the comfort of the manor and its beautiful landscape, she would appreciate the slowness of life in comparison to London.

French artist Berthe Morisot favored the private moments that few get to see. Morisot sat among her Impressionist peers as a key artist in the movement and similarly created from daily experiences. Capturing the fleeting moments of her family and friends, she painted with rapid brushstrokes. Interested in what is transitory, Morisot illuminates domestic life in many of her works.

My ambition is limited to the desire to capture something transient, and yet, this ambition is excessive.

Berthe Morisot, as quoted in: Charles F. Stuckey, William P. Scott, Berthe Morisot: Impressionist, New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1987.

Often using her daughter Julie as a model, Morisot was also a passionate and devoted mother. In Cottage Interior, Julie appears to have risen from the dining table in preoccupation with her doll. With the outside world revealed from a peeled-back curtain, Morisot experiments with the relationship between interior and exterior; the boats floating on the ocean and flowers blooming echo the child’s imagination against the fixed domestic scene.

As a member of Les Nabis, Pierre Bonnard was highly influential in the French and Post-Impressionist art scene. Much like his fellow Nabi, Bonnard viewed color as a fundamental aspect of painting, regularly creating from memory and flavoring his work with the hues it emphasized. Seeking to capture a moment, he was continuously inspired by domestic life and the intimate scenes it provided.

Painting has to get back to its original goal, examining the inner lives of human beings.

Pierre Bonnard. Carnegie Museum of Art.

As an ongoing motif throughout his work, Bonnard repeatedly depicted his wife Marthe de Méligny in the bathtub. Suffering with her health, Marthe believed in hydrotherapy to ease her illnesses. However, Bonnard’s bathroom depictions capture real life while simultaneously warping it. Bonnard commonly depicted his wife as a young woman, despite being in her fifties in the first of his bathing works. Perhaps reflecting Marthe’s hope in rejuvenation, although represented in an unsettling tomb-shaped bath, he blends idealism with everyday subjects. Regardless, Bonnard continuously places accents on the private moments that home brings.

Moving from his native Lausanne to Paris, Félix Vallotton then became a lifelong friend of Bonnard’s. Vallotton remains closely associated with Les Nabis, after joining the group in 1892 and being dubbed ‘the Foreign Nabi’. Similarly inspired by daily life, Vallotton was particularly interested in capturing private, dramatic scenes. Such scenes included nudes, still life, and domesticity, stylistically influenced by Japanese woodblock to create his hard-edged works.

After marrying the wealthy Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques, Vallotton was both intrigued and yet alienated by bourgeois society; this theme is most apparent in his lavish interiors. Often depicting the mysteriously illicit life of the upper class, he creates melodramatic domestic scenes with the strong juxtaposition of color and complex characters. The viewer is left to question the legitimacy of the relationships between the subjects and what situation they may be witnessing. In Interior with Woman in Red Seen from Behind, three doorways invite the viewer’s eye to contemplate the scene. What does the woman in red appear to be gazing at in the bedroom? Why did it capture her attention in the midst of dressing? Left to speculate the woman in red, who was actually his wife Gabrielle, Vallotton’s interior scene remains quietly tense like that of a soap opera.

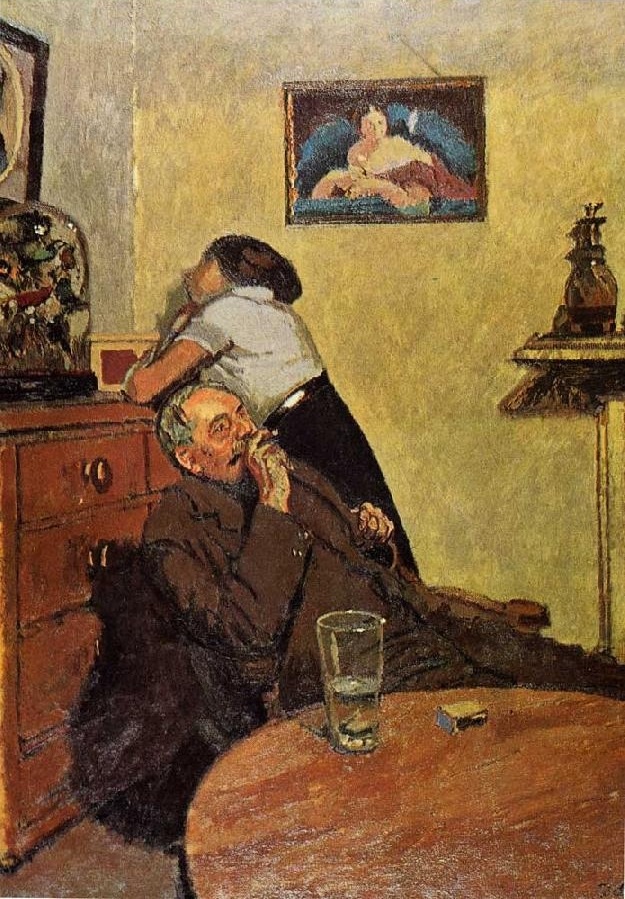

In contrast to Vallotton’s bourgeois Parisian interiors, Walter Sickert was compelled by the everyday life of Britain’s working class. Seeking to depict the lives of ordinary people, Sickert was much inspired by Camden (an inner London suburb with a mixture of middle and working-class occupants). As leader of the Camden Town Group, he strove to create an unromanticized impression of urban life. Using an urban realist style, Sickert thus conveyed the inner lives of his subjects and their typical surroundings.

One of Sickert’s most praised works is Ennui, which depicts a couple in their home. Sickert creates a potent atmosphere in the work, signifying the emotional estrangement between the couple through telling body language and objects. While the male figure gazes into the distance, the female leans on a cabinet with a bell jar on it. Stuffed birds are in the jar, entrapped much like the marital couple, also the glass of water on the table is half empty. As a result Sickert powerfully captures the unspoken tensions of married life and the home, finding inspiration in what goes unsaid on a daily basis.

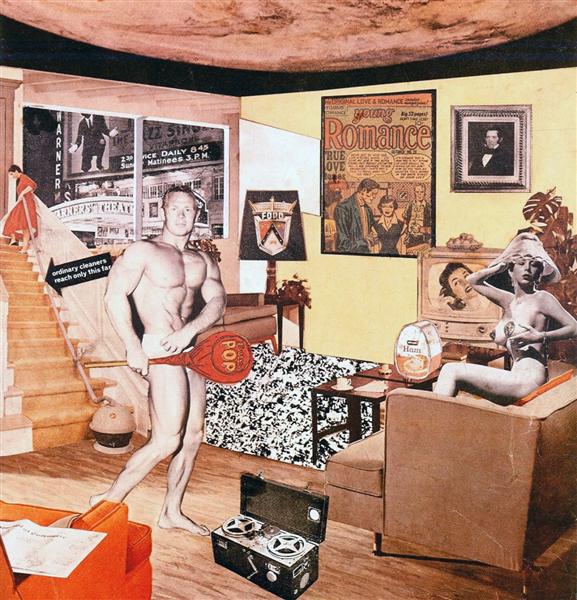

Richard Hamilton also represented the home in many of his works, although through a seemingly more satirical lens than Sickert. Recognized by many as the ‘father of Pop art‘, Hamilton’s practice included both painting and collage. Seeking to explore the post-war consciousness, he formed many interiors throughout his career, using various cuttings to represent the fast rise of consumerism.

Any interior is a set of anachronisms, a museum with the lingering residues of decorative styles that an inhabited space collects. Banal or beautiful, exquisite or sordid, each says a lot about its owner and something about humanity in general.

Richard Hamilton, Collected Words 1953-1982, London and New York, 1982.

Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? is one of the most iconic examples of Hamilton’s interiors. Using material from advertisements in American magazines, Hamilton forms some of the key motifs associated with Pop art: starlets, glamour, hi-tech innovations, and even the term ‘Pop’ itself. Hamilton’s domestic scene is bold, alluring, and chaotic as a result. It is also a powerful allegory of what society would accelerate to become.

Columbian artist Alejandra Hernández also shapes meaning through interiors, using them to reflect her inner subjects. Interested in how we interact with our surroundings, she creates both real and fictional portraits. Previously, Hernández has created a series of works based around domestic narratives; set in familiar environments, the scenes are peppered with various household items to signify personality.

In Las Tres Gracias she subverts the art historical Three Graces into a modern interpretation. Depicting three young women (socks-and-all) lounging on the sofa, surrounded by various fruit, instruments, plants, fairy lights, and other objects, Hernández’s Three Graces are taken from mythology and put into the context of contemporary domesticity. As the unidealized figures merge with recognizable postures, garments, and home attributes, she provides a fresh twist on the classics.

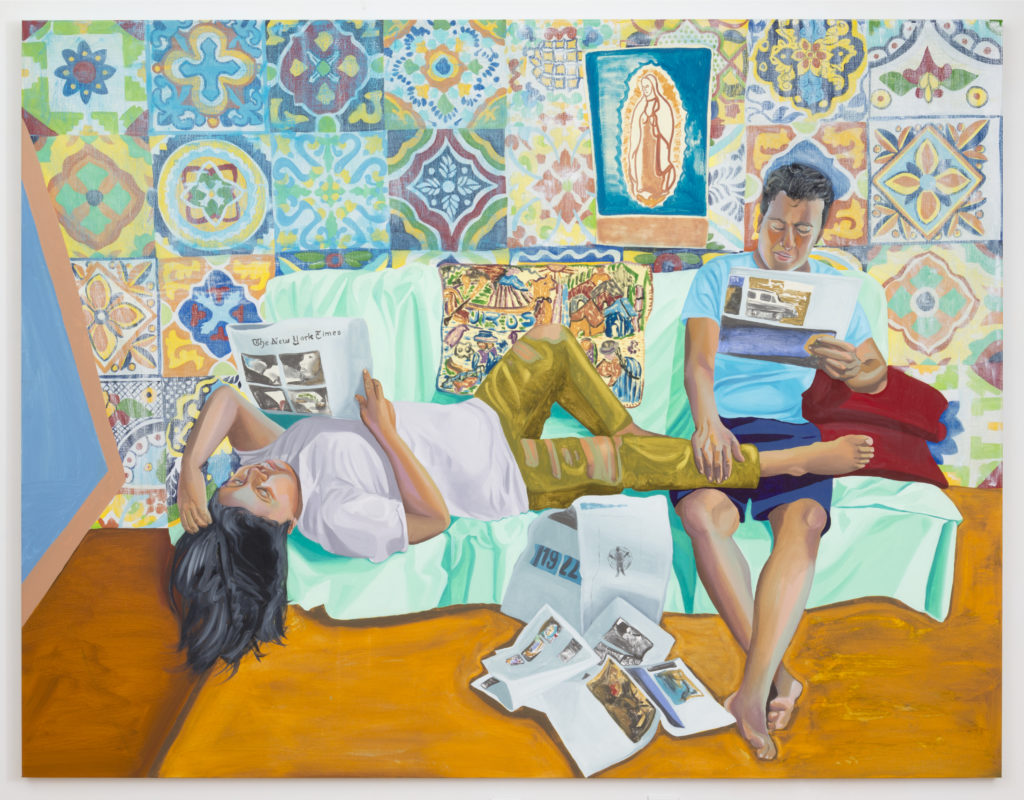

While Hernández depicts both real and imagined people, Aliza Nisenbaum predominantly grounds her work in the existing Mexican and Latin American community. Creating portraits of undocumented immigrant families in New York, Nisenbaum often paints her subjects in their homes. The conversations that arise continuously supplement her artistic process:

I see these compositions as private places for dreaming, where figures become embraced by the spaces surrounding them.

Aliza Nisenbaum. Mousse Magazine.

Using designs from textiles found in the homes of her subjects, Nisenbaum surrounds her sitters in specific patterns as well as recognizable settings. In Las Talaveritas, Sunday Morning NY Times, Nisenbaum’s subjects relax whilst reading the New York Times. Painting from observation, this and many of Nisenbaum’s works are both intimate and social, based on human interaction in a natural setting.

With each of the above works representing domestic life through a unique lens, we are propelled into both familiar and unfamiliar private spaces. Whether we are eavesdropping in Maes’ Dutch household, taking a Bonnard-style soak in the tub, or enjoying the smaller pleasures like reading the newspaper, these artworks help us to escape or relate to the walls around us.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!