10 Iconic Floral Still Lifes You Need to Know

Flowers have long been a central theme in still-life painting. Each flower carries its own symbolism. For example, they can represent innocence,...

Errika Gerakiti 6 February 2025

Throughout the centuries, artists have rendered countless captivating glimpses of the everyday rituals of women, depicting intimate moments of femininity. Across various movements and periods, artists have explored the act of grooming or getting dressed as a means to unravel narratives about societal norms, personal rituals, and the symbolism of attire.

Here, we embark on an exploration of 10 remarkable artworks spanning centuries, each offering a unique perspective on women’s experiences of self-presentation across diverse social and cultural contexts.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Naked Woman (Femme nue), ca. 1889, private collection.

The prominent 19th-century Orientalist painter, Jean-Léon Gérôme, was celebrated for his skillful rendering of historical and Orientalist themes. This painting exemplifies his mastery of the female form within his signature classical framework, highlighting Gérôme’s meticulous attention to detail, and his talent for evoking timeless beauty.

The painting is set in a large public bath with lofty ceilings and arched corridors. Women appear in the background deeply engaged in conversation and in the act of getting dressed. However, the focal point is a nude woman depicted with an ethereal allure, in the mundane process of washing her foot. There is a subtle melancholy in her gaze, suggesting a deeper contemplation. She appears to be acquainted with the woman in the bath before her, perhaps engaged in a deep and long conversation.

Gérôme infuses this painting with grace and tranquility, and emphasizes a delicate sense of vulnerability, particularly in the main figure.

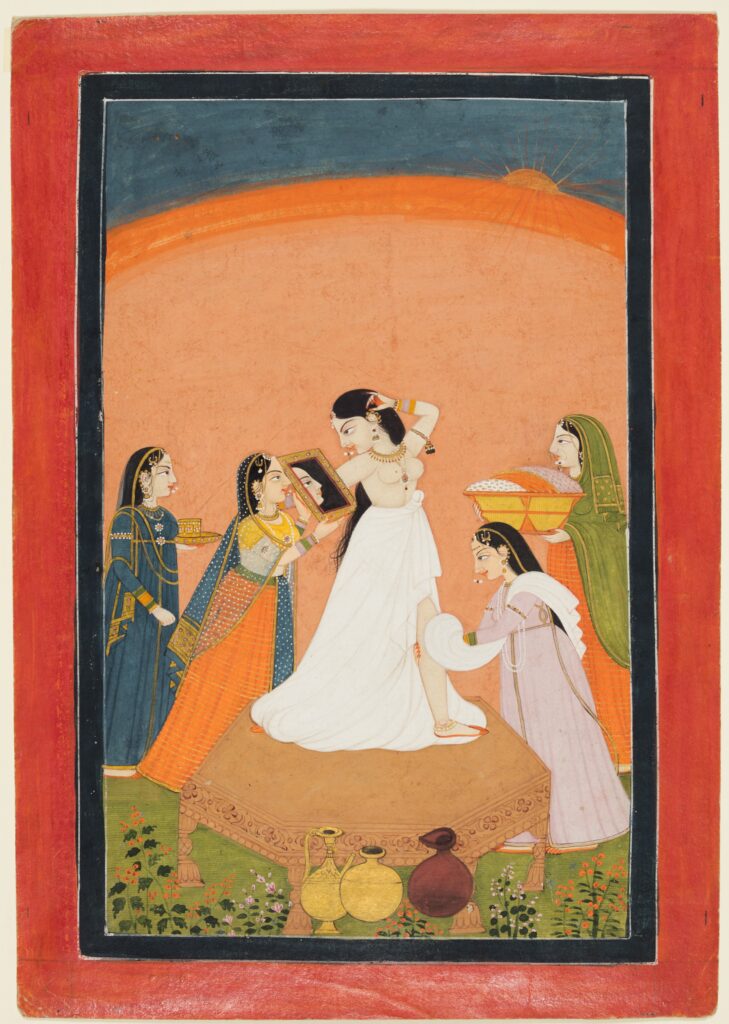

The Morning Toilette, ca. 1810–1825, Cleveland Museum of Art, OH, USA.

This idealized scene from the Pahari School in Northern India depicts an aristocratic woman on a pedestal, draped in pristine white fabric knotted at her waist. An attendant helps dry her leg, while another positions a mirror before her as she gets dressed. Two more elegant attendants attend to her toilette with clothing and other items. Ewers and water pots can be seen in the foreground.

The woman gazes introspectively at her reflection as she tries on a jhumka, a South Asian bell-shaped earring popular to this day. More traditional Indian jewelry is featured, not just on the lady of importance, but also on her elegant attendants. This artwork rendered in gum tempera and gold accents is among the treasures of the Pahari Kingdom of Chamba and serves as a fleeting glimpse of the refinement and beauty of India in the early 19th century.

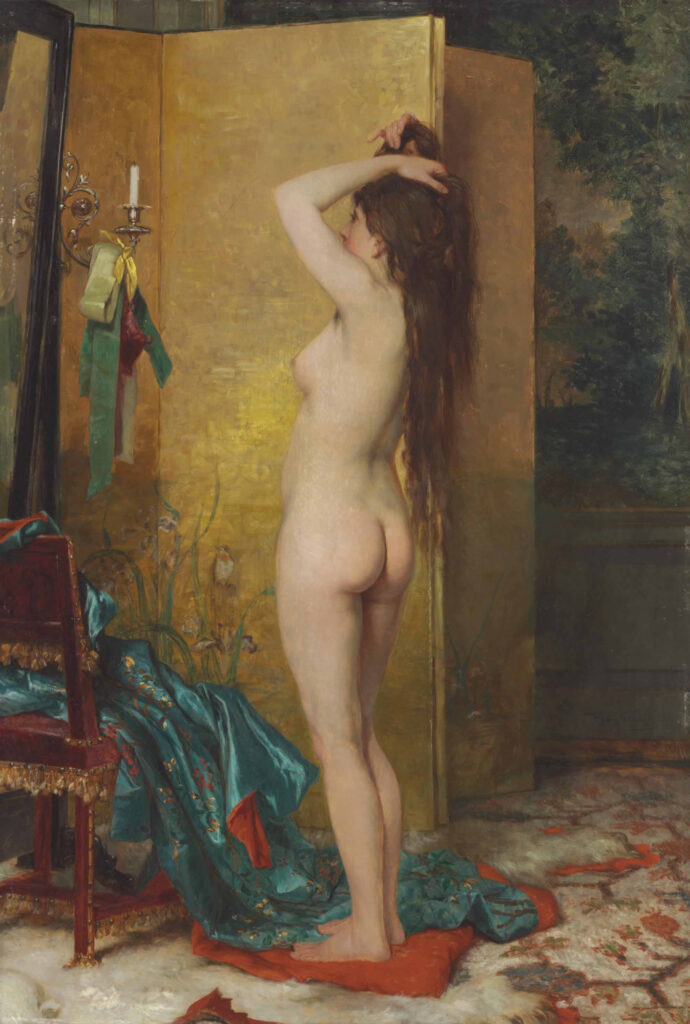

Frans Verhas, A Standing Nude, ca. 1827–1897. Christie’s.

Frans Verhas, a prominent figure in the Belgian artistic scene of the 19th century, was deeply rooted in the country’s academic tradition while also drawing inspiration from the prevailing artistic movements of his time, notably Romanticism and Realism. His oeuvre comprised a rich tapestry of scenes, and he gained acclaim for his depictions of women and children set in opulent interiors.

In this painting, Verhas masterfully renders a moment of quiet intimacy. The subject stands atop a luxurious teal silk fabric adorned with floral motifs, possibly recently discarded in what appears to be the tranquil moments of dawn. She arranges her hair in the mirror before her and prepares for the day ahead.

Verhas’ interiors are known for their grand opulence and showcase his great skill in depicting a variety of textures in the form of tapestries, silks, wood, and metals. In this painting, lush vegetation adorns the mural backdrop, complete with painted wainscoting and ornate rugs that add to the sense of luxury. A candle sconce serves as both a source of gentle illumination and a practical ribbon holder, underscoring the familiarity of the moment.

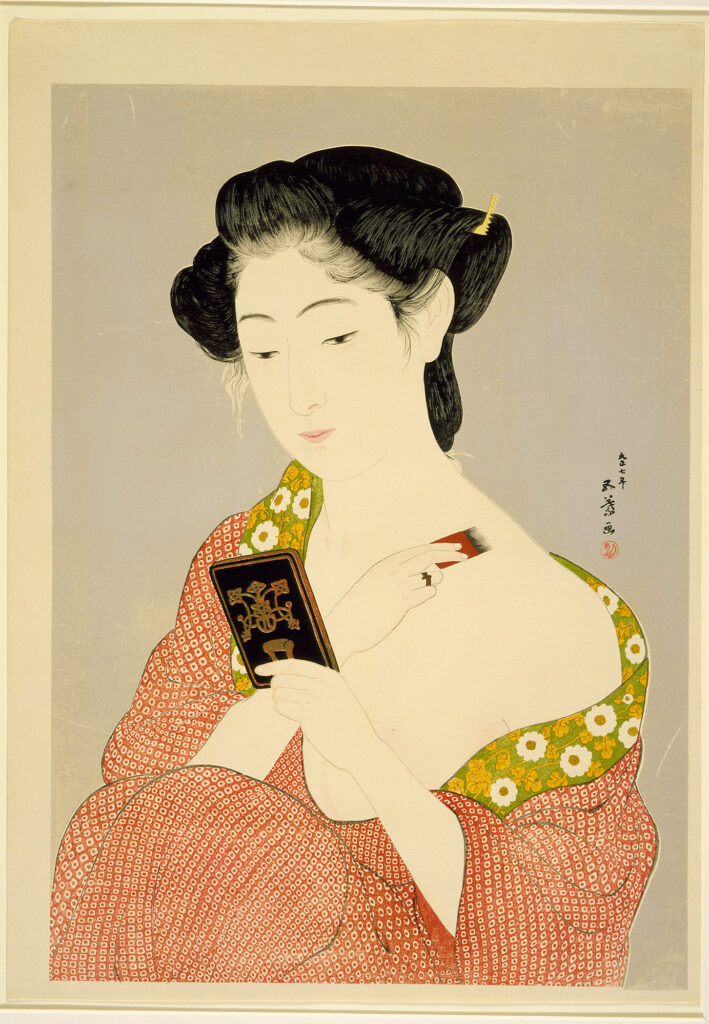

Hashiguchi Goyō, Woman at Toilette (Keshō no onna), ca. 1918. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Hashiguchi Goyō, born in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan in 1880, was a renowned ukiyo-e artist who made a lasting impact on the world of Japanese woodblock prints. Initially trained as a painter, he mastered traditional Japanese painting techniques before transitioning to woodblock printing. Goyō gained prominence for his exquisite prints featuring elegant Japanese women in various poses and settings, showcasing his distinctive style characterized by subtle elegance.

In this particular print, an elegant woman wrapped in fabric is depicted applying cosmetics with a small hand-carved mirror, highlighting Goyō’s attention to detail. Utilizing a limited color palette, he imbued a sense of intimacy and introspection into his prints. Despite his untimely death at the age of 41, Goyō’s art experienced a posthumous resurgence, continuing to captivate audiences with its timeless beauty and cultural significance.

Georges Seurat, Young Woman Powdering Herself, ca. 1889–1890, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK.

In this portrayal, rendered from a pointillist perspective, a woman delicately engages in the act of powdering her face, a gesture of refinement and femininity. Surrounding her is a display of beauty products, likely a cosmetic kit, marking an advancement in the cosmetic industry of the time and the evolving practices of self-care and adornment. The sitter, believed to be Madeleine Knobloch in the process of getting dressed, has been lovingly depicted by Georges Pierre Seurat, a leader of the Post-Impressionists and inventor of pointillism.

Knobloch, also Seurat’s lover, is featured in several of his works, and her presence is a recurring motif in his oeuvre. Here, she is comically out of scale with her tiny Rococo dressing table, yet the portrayal is imbued with a fondness that transcends mere representation. Gazed upon with tenderness, Knobloch’s image carries a poignant undertone—it is believed she was pregnant at the time, only to lose her child shortly after Seurat’s untimely death in 1891.

Samuel Luke Fildes, An Al Fresco Toilette, ca. 1889, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, UK.

Samuel Luke Fildes, a renowned British painter and illustrator, was generally known for his focus on portraiture. However, this particular work stems from a series inspired by his travels to Venice. Originally titled Morning of the Fiesta, it vividly depicts the preparations leading up to a festive event later in the day.

In this scene, a Venetian courtyard is adorned with vine-covered trellises, creating a picturesque frame for the female sitters depicted within. The morning sun illuminates the courtyard, casting a warm glow on the three women engrossed in conversation as they anticipate the upcoming event.

The focal point of the painting is a seated woman, her long red tresses being groomed by another woman. A half-finished crochet project lies abandoned on her lap, momentarily forgotten. She exudes a sense of relaxation and engagement in conversation with the woman across from her. In the background, two young children are depicted, immersed in their conversations and preparations, adding a sense of liveliness to the tranquil setting.

Anders Zorn, Woman Dressing, ca. 1893, private collection.

Anders Zorn, a Swedish painter and etcher, drew much of his inspiration from his native Sweden, infusing his works with natural and rural themes. Zorn excelled in various artistic mediums, which contributed to his widespread acclaim. He became particularly known for his portraits and depictions of the female nude, attracting clients from all over the world.

In this work by Zorn, he demonstrates his talent for capturing intimate moments with a sense of warmth and authenticity. Rendered in an Impressionist style, the painting depicts a woman fastening her outfit, bathed in soft, diffused light. Zorn’s vigorous brushstrokes imbue the scene with a palpable sense of movement, while the delicate rendering of the woman’s form and the intricate folds of her clothing add to the painting’s depth. Zorn achieved international renown during his lifetime, leaving behind a legacy of masterful artistry and timeless elegance.

Jean-André Rixens, Young Naked Woman Doing Her Hair (Jeune Femme Nue se Coiffant), ca. 1887, private collection.

Jean-André Rixens, a distinguished French painter from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, garnered renown for his mastery of classical scenes and portraiture. Trained at esteemed institutions throughout France, he became a virtuoso of the academic tradition, evident in the meticulous compositions of his works. Rixens’ pieces emanate an aura of intimacy and aesthetic allure, drawing viewers into a moment of serene contemplation.

In this beautiful painting, Rixens portrays a young woman grooming her hair as she prepares to get dressed. The scene captures her with delicate precision as she tends to her reflection in an elaborate mirror. A palpable tranquility permeates the atmosphere, accentuated by the gentle play of light and the embellishments of lace and furs that adorn her surroundings. The hairbrush and powder placed before her, and the cream taffeta dress draped over an upholstered chair beside her, hint at the forthcoming preparations for the day ahead.

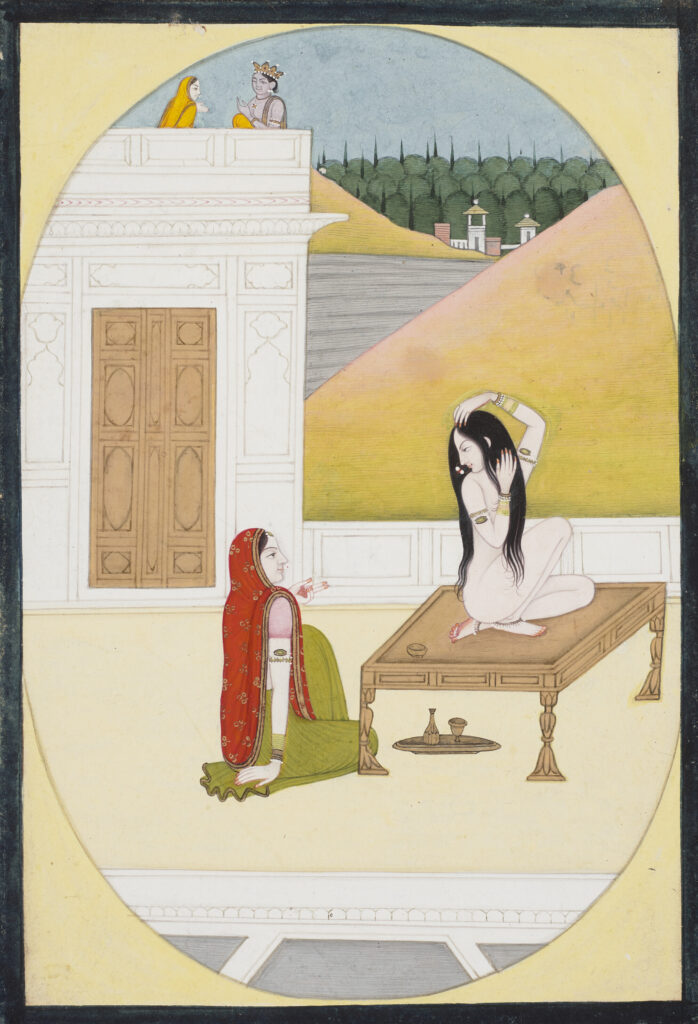

A Painting of Radha at her Toilette, ca. 1820. Christie’s.

Radha, the consort of divine Krishna, emerges as a poignant figure in Hindu mythology, her mortal presence intertwined with the eternal essence of love and devotion. Embedded within the rich tapestry of North Indian art and traditions, their legendary union transcends time, blending the celestial narrative of love and longing with the familiarity of everyday domestic rituals.

This timeless saga finds expression in a scene from a 17th-century Bihari poem where Radha is depicted in the nude, adorned with luscious tresses and draped in gold jewelry, in a moment of intimate vulnerability. Seated before her, a messenger clad in traditional attire delivers a tender message, urging her to alleviate Krishna’s sorrow. Meanwhile, in the left foreground, the blue-skinned Krishna, adorned with his iconic peacock feather, gazes upon Radha from a distant perch, accompanied by a female attendant, his anticipation palpable.

Amidst the rich accouterments of Radha’s toilette, this scene evokes the eternal dance of love between mortal and divine, a timeless narrative woven into the fabric of Indian mythology.

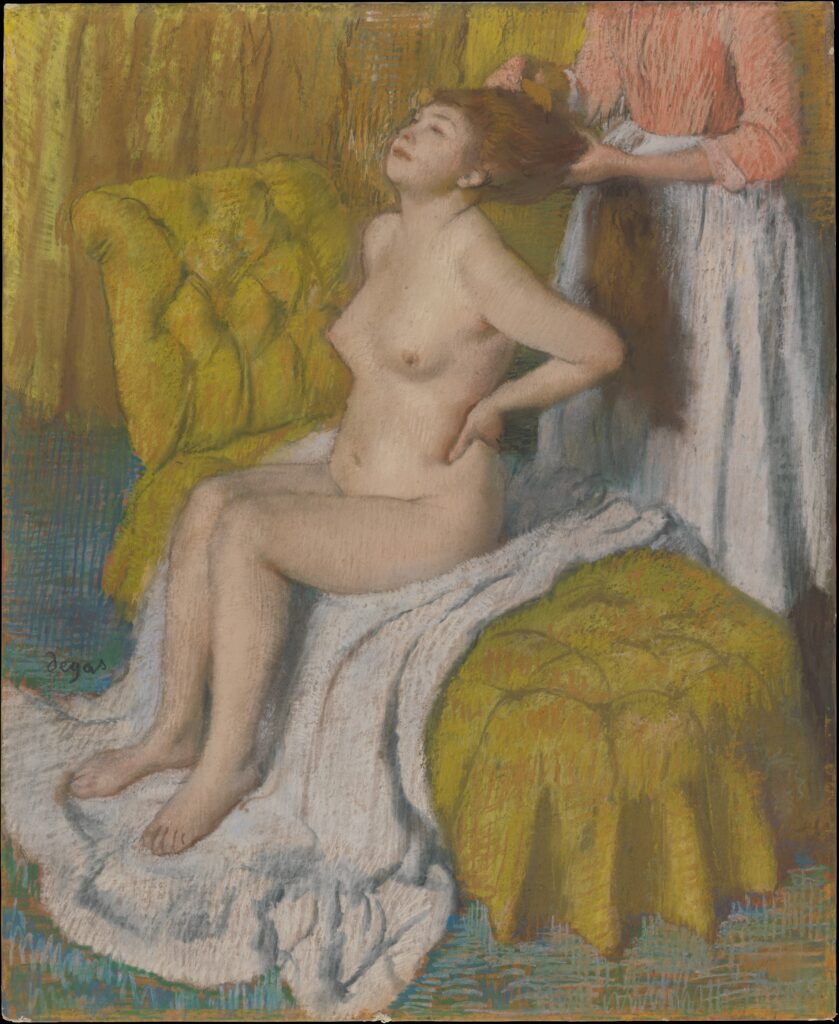

Edgar Degas, Woman Having Her Hair Combed, ca. 1886–88, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

French Impressionist Edgar Degas was well known for his lifelong fascination with the intimate moments of women’s lives. He rendered countless portrayals of ballet dancers in preparation, women getting dressed, and other glimpses into their private lives.

Executed on a grand scale with meticulous attention to detail, Degas portrays a nude figure, reminiscent of Rembrandt’s iconic Bathsheba at Her Bath. Degas’ rendering stands out with its pastel hues, depicting the woman having her hair combed with a more natural flow of movement than can be expected from Rembrandt’s more idealized portrayal.

It was intended to be included in the 1886 Impressionist exhibition but never made it. Whether it was simply not completed in time or deliberately excluded remains unknown.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!