The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

The exhibition Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art at the Barbican Art Gallery in London explores textiles as particularly expressive, evocative, and symbolic media of art production, by presenting a variety of artworks by an intergenerational list of artists active from the 1960s to today all around the globe. The exhibition is co-curated with the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where it will move in September 2024.

Textiles have been repeatedly explored by artists in the last century, especially by women artists – think, for example, of world-renowned artists like Louise Bourgeois and Annie Albers. Given their link with domestic activities and hence femininity in a patriarchal society, women artists have felt the urge to confront themselves with textile-based art, to re-appropriate this medium and claim its artistic value, questioning in this way its gendered attribution.

Textiles have often been dismissed as a craft practice to produce utilitarian objects, hence inferior to other artistic media. But, precisely because of this, they come charged with the materiality of tactile experiences, inhabiting intimate spaces of our everyday life. Textiles can appeal to the senses and to a myriad of personal memories, embodying a huge, yet underexplored expressive potential. Indeed, not many exhibitions have given an overview of the power of textiles in art as a vehicle of multiple meanings and experiences.

This is the goal of the exhibition Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, which opened early in February this year at the Barbican Center in London and will remain there until 26 May 2024.

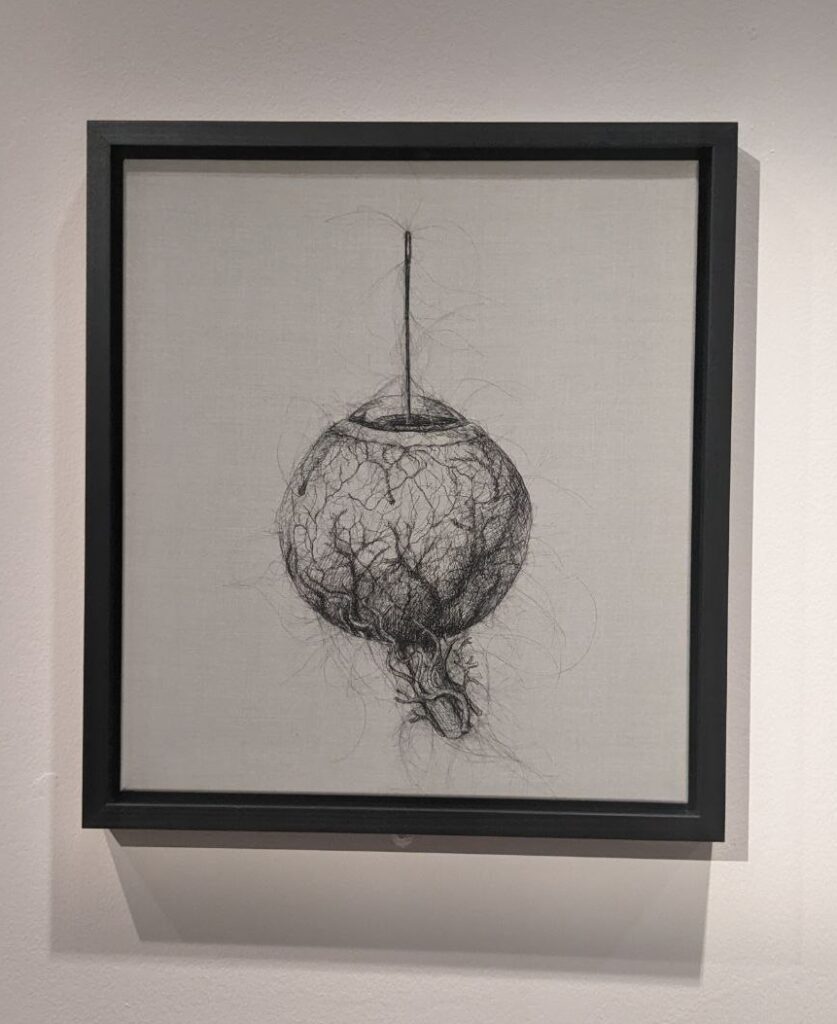

Angela Su, Sewing Together My Split Mind: Straight Stitch, 2020, exhibition view of Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

There are multiple forms of artistic expression through textiles that this exhibition allows us to appreciate. First, textiles can symbolize a healing journey; to sew is a powerful metaphor of care and repair in the aftermath of devastation. The artist Angela Su evokes the pain that comes with repair through images of a needle puncturing body parts (a nipple, an eye, and a vulva), obtained by stitching with hair. The artist herself accompanies these artworks with the words: ‘Suturing is about trying to heal, but it’s very painful. How do we heal after traumatic experiences? Can we, or will there always be a scar?’

Similarly, the repetitive and mechanical gestures involved in sewing transform it into a reflective and meditative act to process lived experiences. Some of the artworks are the result of moments of shared reflection and elaboration by a community, enhanced through the process of assembling and stitching textile materials.

Examples are the sculptures proposed in Space in Between by the artist Margarita Cabrera. They were made during workshops where participants from Spanish-speaking communities were asked to recollect their memories of the experience of migration through the United States-Mexico border. Participants then embroidered them on soft sculptures through a traditional embroidery technique of the Otomi people of central Mexico.

In these sculptures, the artist chose to give form to a typical element of the landscape of the Southwestern United States, cacti, using abandoned military uniforms from border agents. Everything in this artwork, from the representation target to the medium to the creative process, is designed to be a vehicle of the multiple and divided identities of being a migrant.

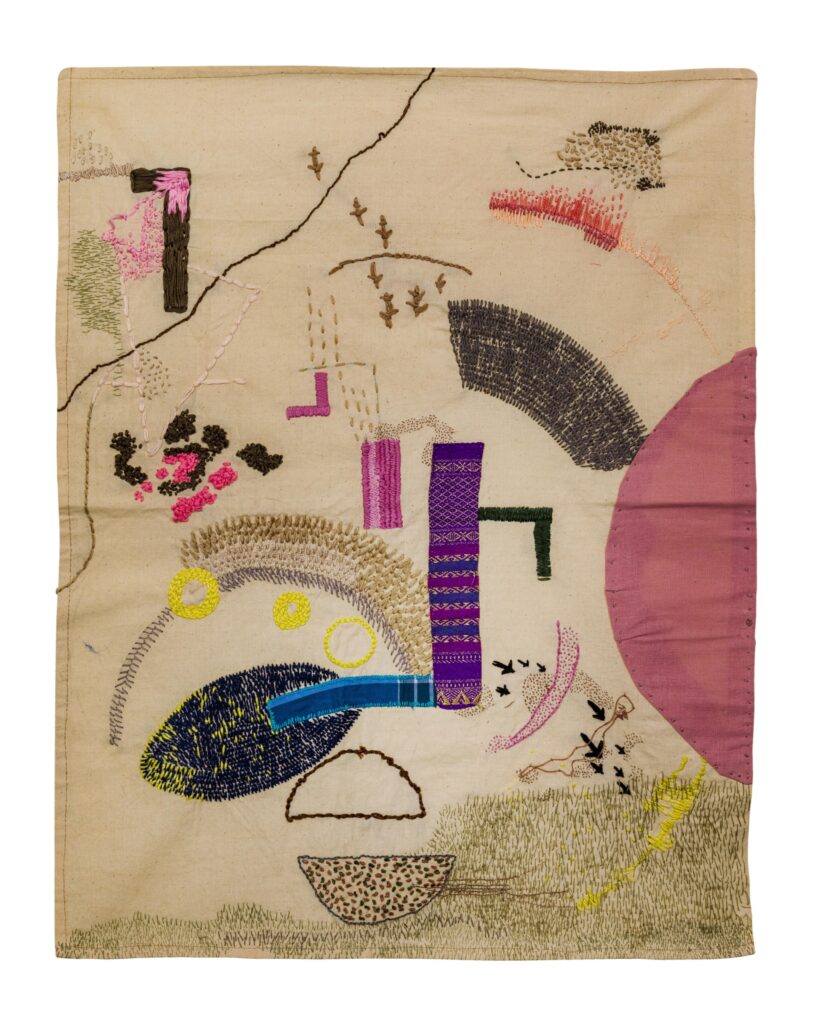

T.Vinoja, Bunker & Border, 2021. Artist’s website.

Textiles, with their structure and tactility, are a privileged means to symbolize, and hence narrate, intricate life paths and to convey material experiences, including the traumatic experience of war. The artist T. Vinoja witnessed the disasters of war while living in Jaffna, the city most affected by the civil war in Sri Lanka. Her stitching-on-fabric work Bunker & Border carries aerial views intertwined with personal memories of shelters, forced displacement, and re-drawn borders.

The therapeutic and recuperative potential of textiles is expressed here at its maximum through their materiality, as during the war they were used to cover wounds and to build temporary shelters. Such a meaning of textiles resonates with Joseph Beuys’ art, in which the insistent presence of felt drew upon his personal experience of being rescued from a wreckage and kept warm with felt during World War II.

Sheila Hicks, Family Treasures, 1993, exhibition view of Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

However, textiles also allow artists to engage with modest materials that thread the texture of our daily lives. Being constantly worn and touched, they become sources and receivers of personal feelings and connections. As a concrete testament to this, artist Sheila Hicks in her Family Treasures exhibits items of clothing from family members and friends. They are transformed into metaphors of personal affection by wrapping and hiding them with colorful threads like gifts.

Several artists have made an explicitly political use of textiles. Textiles can become concrete traces of crimes committed, as a way to denounce, remember, and invite reflection. We see, laid horizontally in the dark as if on an autopsy table, two patchwork tapestries by the artist Teresa Margolles. They carry traces and impressions of killed bodies – one of them was laid on the ground where a black man, Eric Garner, was assassinated in Staten Island. Teresa Margolles worked collaboratively with embroiderers who were close to the victims – like from the Harlem Needle Arts Institute in the case of the tapestry in honor of Eric Garner – to make these tapestries potent mementos bearing witness to violence for the collective memory.

Combined with traditional techniques of textile making, textiles can become tools to expose and remind of historical episodes of colonial domination and human exploitation. The quilts presented by the artist Sanford Biggers recall their use as maps to signpost routes to freedom for enslaved people in the United States. Violeta Parra uses embroidery to narrate and denounce violent episodes of the Spanish conquest of Chile. Chilean Arpilleras, patchworks stitched onto discarded scraps of fabric (like from food sacks), were made in workshops by women from the outskirts of Santiago to document the reality of poverty and hunger, as well as the murders and imprisonment of family members, during the Pinochet regime.

Tau Lewis, The Coral Reef Preservation Society, 2019 © Tau Lewis, Courtesy the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles.

In a gigantic tapestry by Tau Lewis, not only the subject (the ‘middle passage’ of enslaved Africans), but also the choice of the fabric has a historical and political significance. Cotton fibers dyed in indigo call attention to the colonial system of power that framed the production and global trade of textiles, further alluding to a history of slavery and resource exploitation.

Kevin Beasley, Phasing (Flow), 2017, exhibition view of Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

Materials in textile artworks are often reused and re-converted to release an alternative symbolic potential. The artist Keavin Beasley takes housedresses from a dress shop in Harlem, New York, and casts them in resin to transform them into sculptures. In this way he evokes the bodies that could, or have, inhabited them at some indefinite time. The artist Magdalena Abakanowicz invented a new sculptural vocabulary of biomorphic entities through her Abakans. These works mix plant fibers with discarded materials into large-scale hand-woven sculptures.

Jagoda Buić, L’ange chassé (Fallen Angel), 1967, exhibition view of Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

The artist Jagoda Buić created ‘tapestry situations’, as she called them, made with raw fibers. They pay homage to the ecological landscape of her native land, Yugoslavia, while their shapes echoed Dubrovnik’s towers. Mrinalini Mukherjee weaved deities, merging Indian iconographies and local craft practices, twisting and braiding ropes found in New Delhi’s markets.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Pakshi, 1985, exhibition view of Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

Textiles carry an intrinsic symbolic weight through the image of the connection between individuals, with nature and our past history. The artist Antonio Pichillá Quiacaín in the artwork Cordón Umbilical invests textiles with this deeply symbolic meaning. For the artist, a loom fixed to his abdomen with threads wrapped around a tree ‘represents the connection of the body with the textile, the textile with the trunk of the tree, the tree with its roots in nature’.

Cecilia Vicuña, Quipu Astral, 2012, exhibition view of Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican, London, UK. Photograph by Barbara Bravi.

At the same time, ancestral histories are called upon to unfold in the materiality of textiles. The artist Cecilia Vicuña, in the installation Quipu Astral, proposes a ‘poem in space’ (as she defined it). It is made of colorful stretches of unspun wool hanging down from the ceiling, which recalls the technique of Quipu (‘knot’ in the Quechua language) as way to create connections with her people’s ancestry and with the cosmos.

The exhibition Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art is a journey through attempts of re-appraisal of textile making in art, as a means for expression, experimentation as well as reconnection with traditions and ancestral histories. Imbued with political messages and personal memories, conveying subversive acts or the affirmation of queer identities, in this exhibition textiles prove to be able to disclose much more expressive power than art history and museum contexts have ever attributed to them.

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art is on view at the Barbican Art Gallery till 26 May 2024.

Author’s bio:

Barbara Bravi is an art lover originally from Italy but currently based in London. She makes a living by working as a university lecturer in biomathematics, yet she spends most of her free time visiting art exhibitions. As such, she is deeply fascinated by the intersections between art, mathematics, and science in general.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!