Summary

- The famous Egyptian queen Cleopatra was a popular subject in Western art since the late Middle Ages. She was often used by male artists to portray a beautiful and sexually available woman for a male audience.

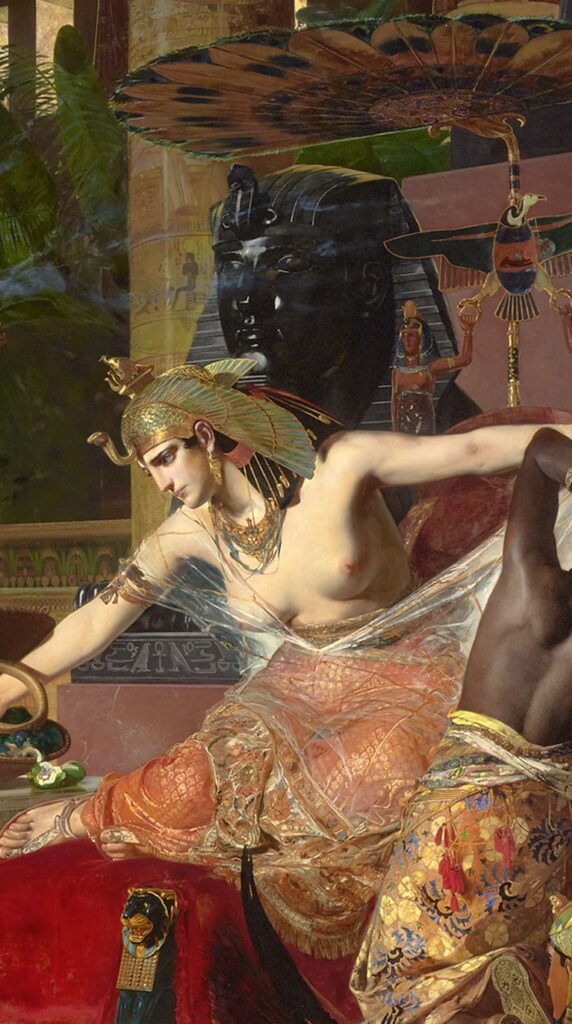

- In the 19th century, she was additionally put in an exoticized setting to emulate a Western phantasma of ancient Egypt. Austrian painter Hans Makart gives an example with his Death of Cleopatra from 1875.

- The subject became increasingly interwoven with the genre of Orientalism, in which Middle Eastern and North African cultures are predominantly characterized as the ‘exotic Other.’

- Cleopatra appears almost exclusively as a light-skinned woman, while her servants are frequently represented as dark-skinned, especially in the 19th century. Her case proves the Western construction of White women being more attractive than their Black and Brown sisters.

The History of Cleopatra in European Art

Makart‘s sumptuous painting is one in a long series that depicts the ancient queen, who ruled over a cosmopolitan empire in North Africa, as White. Since the Renaissance, she was a popular subject featured in diverse media, often with a sexual undertone.

Racism in Western Art: Guido Reni, Cleopatra, 1635-1640, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, Italy.

In Makart‘s age of imperialism and the West‘s cultural obsession with everything ‘foreign,’ Cleopatra was increasingly placed in an exoticized setting. The Death of Cleopatra is an ideal case to track European artists‘ involvement in creating the romanticized vision of a ‘mysterious Orient’ with submissive women at White man‘s disposal, and the vision of a clear balance of power based on race. Our journey begins far away from the Nile at yet another vast river: the Danube and the imperial capital of Vienna.

Hans Makart – Vienna’s Klimt Before Klimt

Any self-respecting art collector in Belle Époque Vienna could not get past Hans Makart (1840-1884), the city‘s uncrowned prince of painters. Renowned for history paintings and portraits of society women, his use of brilliant color, beautified nudes and huge formats appealed immensely to the imperial crème de la crème. Makart‘s primary concern with aesthetics rather than political ideals would influence the Secession artists succeeding his legacy, such as Gustav Klimt.

Makart and Orientalism

The genre of history painting, in which he excelled, was deemed the supreme class of art of the day. Scenes from history, classical mythology, and the Bible–one could hardly imagine a wall in a palace or public building not adorned with them. A relatively new subgenre that conquered the halls of the 19th century in a flash was that of Orientalism. The term refers to the Western representation (often fantasies) of the cultures and nations of the Middle East and North Africa. The theme was an artistic response to Europe‘s conquest and division of the world, often carrying a sense of Western paternalism towards the colonized peoples.

Hans Makart, aware of the ‘exotic craze’ on the art market, created 16 such works, ranging from portraits to everyday life and historical scenes. Strikingly, six of them depict no one else but Egypt‘s number one female ruler. And why would they not? Cleopatra‘s story enabled the artist to indulge in his favorite topics: decadence and the sensuous flesh of beautiful women set in a world outside his own. Two of the paintings portray Cleopatra‘s death, while another shows her on a boat trip along the Nile. The rest are oil sketches for the latter. One version from the artist‘s early career is considered lost.

Several events in Makart‘s life could have pushed his dialogue with Orientalist topics. At the 1873 Vienna World‘s Fair, the palace of the Egyptian viceroy was reconstructed, as was a Turkish coffee and residential house. Multiple Orientalist paintings were exhibited at the venue. The same year also witnessed the foundation of an Oriental Museum in Vienna, whose collection is part of the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) today. Probably the most memorable experience was a journey that the artist took to Egypt in the winter of 1875/1876. One wonders how these factors might have influenced Makart‘s conception of our painting in question.

An Orientalist building at the Vienna World’s Fair of 1873, Photograph by György Klösz/Wiener Photographen-Association, Vienna Museum, Vienna, Austria.

The Death of Cleopatra

Hans Makart’s The Death of Cleopatra is dominated by the half-naked, bejeweled figure of a White Cleopatra, who rests on a divan and gazes upwards. The snake she clasps in her hand confronts us with her alleged suicide by poisoning with the animal‘s bite to evade capture by her adversary, the Roman consul Augustus. Two Black female servants or slaves accompany their mistress. One‘s bare-breasted body lies at the queen‘s feet, apparently already dead, while the other covers her face in grief or horror with her hands. The setting is an undefined room lavishly decorated with luxury items. The composition conveys a strong aura of sensuality paired with theatricality.

A truthful portrayal of Cleopatra‘s epoch, Hellenistic Egypt, does not seem to have been the goal: the pomegranate ornaments on the curtain seem more at home in a Renaissance or Baroque palace. And the tiger skin in the foreground also appears out of place. Even an object we associate with ancient Egypt has traveled back in time. The conspicuous vulture crown Cleopatra wears in the painting was actually worn by royal consorts from previous dynasties.

Racism in Western Art: Hans Makart, The Death of Cleopatra, 1875, New Gallery, Kassel, Germany.

All in all, Hans Makart‘s painting is a colorful hodgepodge of anachronism and anatopism. Interestingly, the artist was criticized in his own time for not caring for historical accuracy; instead, he created art that primarily stimulated the senses of his audience, unlike most of his colleagues of the history genre, who strove for (presumed) historical authenticity.

Hans Makart‘s agency of beauty becomes obvious in The Death of Cleopatra, in which the narrative is but a subplot to the irresistible eroticism of female nudity expressed in the women‘s seductiveness and luminous colors. The overt sensuality, despite the tragic content, makes it all too clear that this painting does not aim at storytelling. The woman crossing her hands over her face embodies the only tangible drama, as even her deceased peer is staged as an alluring nude. Makart‘s other, much smaller painting of Cleopatra‘s death is also conceived as a feast for the senses. Notably, the artist did not use any anonymous model for Cleopatra, but no one else than Charlotte Wolter (1834-1897), Vienna‘s most celebrated and beloved actress.

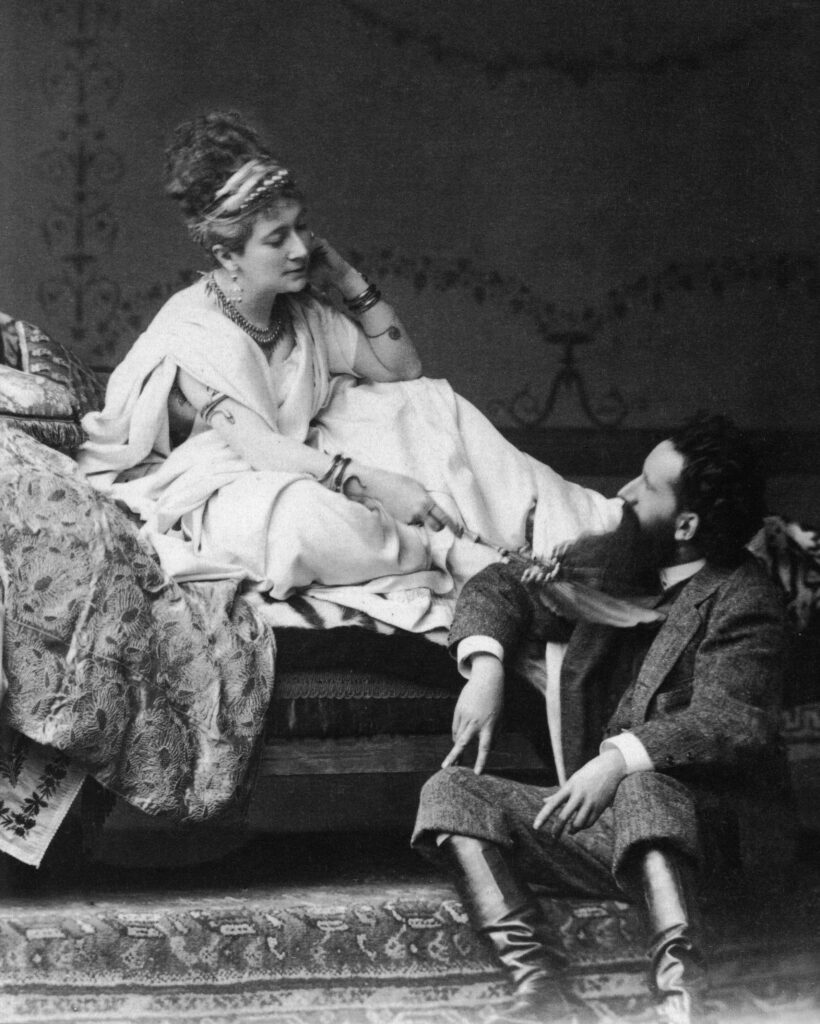

Charlotte Wolter and Hans Makart, 1875, Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Wolter, who succeeded by playing tragic-heroic characters, was the epitome of a late 19th-century star. Naturally, a fair amount of people recognized the illustrious model when the paintings were displayed in the House of the Artists in 1876, Austria‘s leading exhibition venue. The artworks were purchased by Baron Leitenberger and later noteworthily by Adolph Hitler for his ideological art project of the Führermuseum in Linz.

Cleopatra – The Secret of Her Origin

Charlotte Wolter‘s identity, which was effective in the public eye, brings us back to our original topic. Not only did Makart impersonate a European actress as a North African queen, he even made Wolter‘s light skin the visual focus of the painting! The literal whiteness of Cleopatra radiates through the painting, theatrically enhanced by the gold and red hues surrounding her. The white color Hans Makart applied for the skin is unnatural for a real human body and gives the appearance of a statue carved out of alabaster.

Racism in Western Art: Hans Makart, The Death of Cleopatra, 1875, New Gallery, Kassel, Germany. Detail.

And he was not the only one visualizing Cleopatra as light-skinned. Jean-Léon Gérôme, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Eugène Delacroix: the big players of 19th-century history painting all (re)produced this image. Did the real Cleopatra truly look like this?

The furious debate following Netflix‘s release of the docu-series was led by two major parties. One side insisted that Cleopatra‘s family‘s descent – the Ptolemies were a Macedonian Greek royal house – and their extensive engagement in sibling marriage, concludes they must have been White.

The opposition argued that the pharaohs had concubines which included women from all different parts of the multi-ethnic kingdom, e.g. dark-skinned Egyptians or Nubians. Accordingly, a possible origin of Color of Cleopatra could be given since the identity of both her mother and paternal grandmother remain unresolved.

In any case, her contemporary portraits in sculpture and coinage speak for a bicultural identity as Greek and Egyptian. Due to the stylization, however, it’s difficult to judge her real appearance. Any clear archeological or written evidence to shed light on the discussion is yet to be found.

None of the many 19th-century visual representations make the smallest concession to a potential Black or Brown background of Cleopatra. However, the predominant portrayal with black hair contrasts the typical blondes and brunettes usually depicted in art from the 16th to the 18th centuries. This could at least be interpreted as a contemporary Western perception of Cleopatra as a person from the Eastern Mediterranean. The idealized so-called ‘Greek profile’ in some paintings, such as those by Alma-Tadema or Julius Kronberg, could account for an awareness of the Ptolemies‘ Macedonian Greek roots.

Hans Makart‘s dream of a Snow White with auburn hair does no such thing. It rather expresses one man‘s erotic desires as well as the clever marketing of a superstar. His further paintings depicting White models in the role of People of Color such as Japanese Woman affirm Makart‘s indifference towards authentic portrayal of non-Western subjects.

Racism in Western Art: Hans Makart, Japanese Woman, c. 1870-1875, Upper Austrian Regional Museum, Linz, Austria.

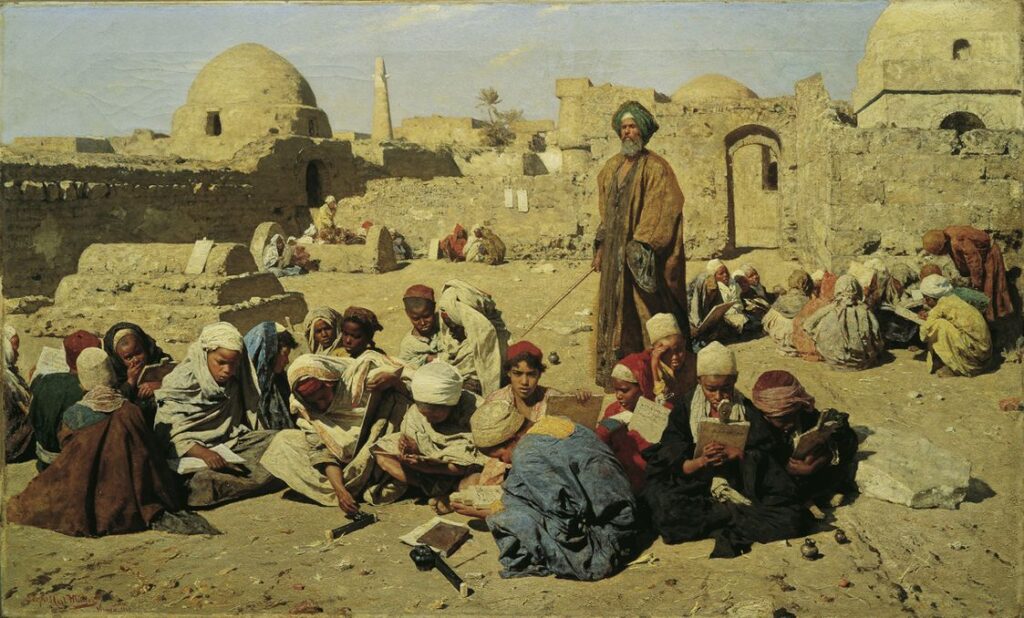

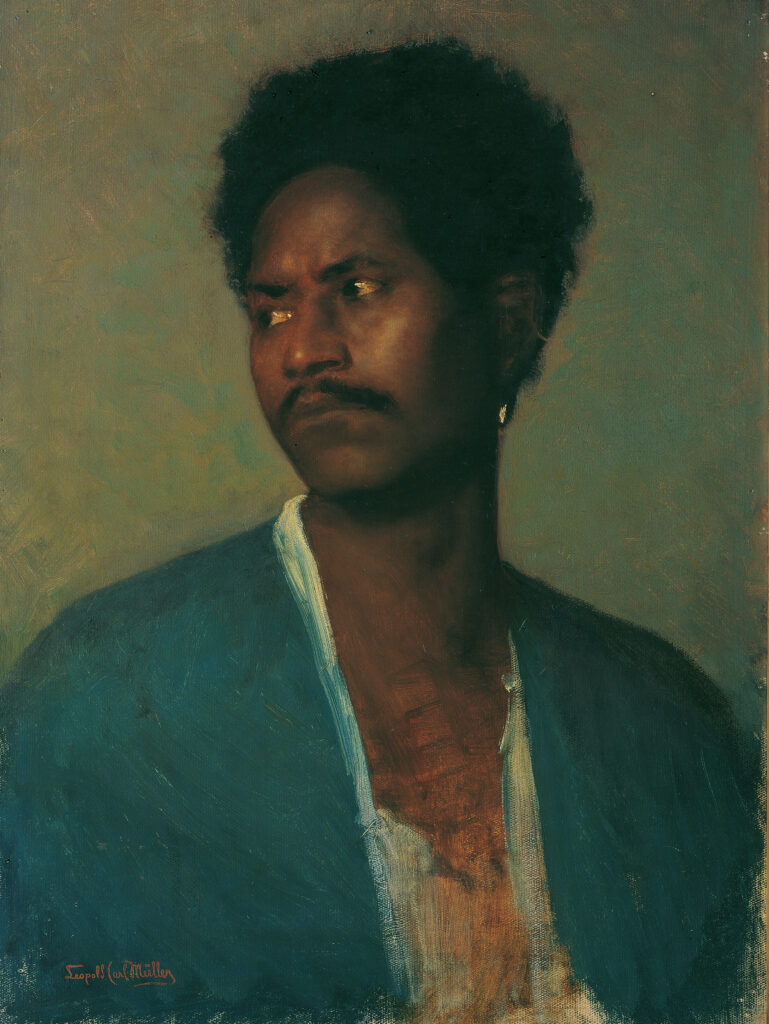

As a matter of fact, his Orientalist paintings would be described by many today as cultural appropriation. Makart collects pieces from different, unrelated origins and weaves them together for the main purpose of visual appeal. This message becomes even clearer when we compare him with his colleague and friend Leopold Carl Müller (1834-1892), Austria‘s most significant Orientalist. Müller‘s naturalistic, everyday life scenes of contemporary Egypt and portraits of locals testify to a strong empathy for his models. He bestows on them a dignified posture, from which Hans Makart‘s decorative female fantasies differ fundamentally.

Black People in Western Painting – Forever Servitude?

So what about the two servants in Hans Makart‘s embellished monument of ‘faraway cultures?’ Quickly summarized: they are in accordance with the Western depiction of Black and Brown people primarily as servants and slaves. Despite some dignified autonomous portraits and representations as saints, until the 20th century the focus was on their subordination to White people. This becomes unmistakable in double or group portraits, where Black people‘s skin was often deliberately contrasted to their masters‘ and mistresses‘ as visual accentuation.

Racism in Western Art: François de Troy, Portrait of Elisabeth Charlotte of Orléans and her Slave, c. 1680, Palace of Versailles, Paris, France.

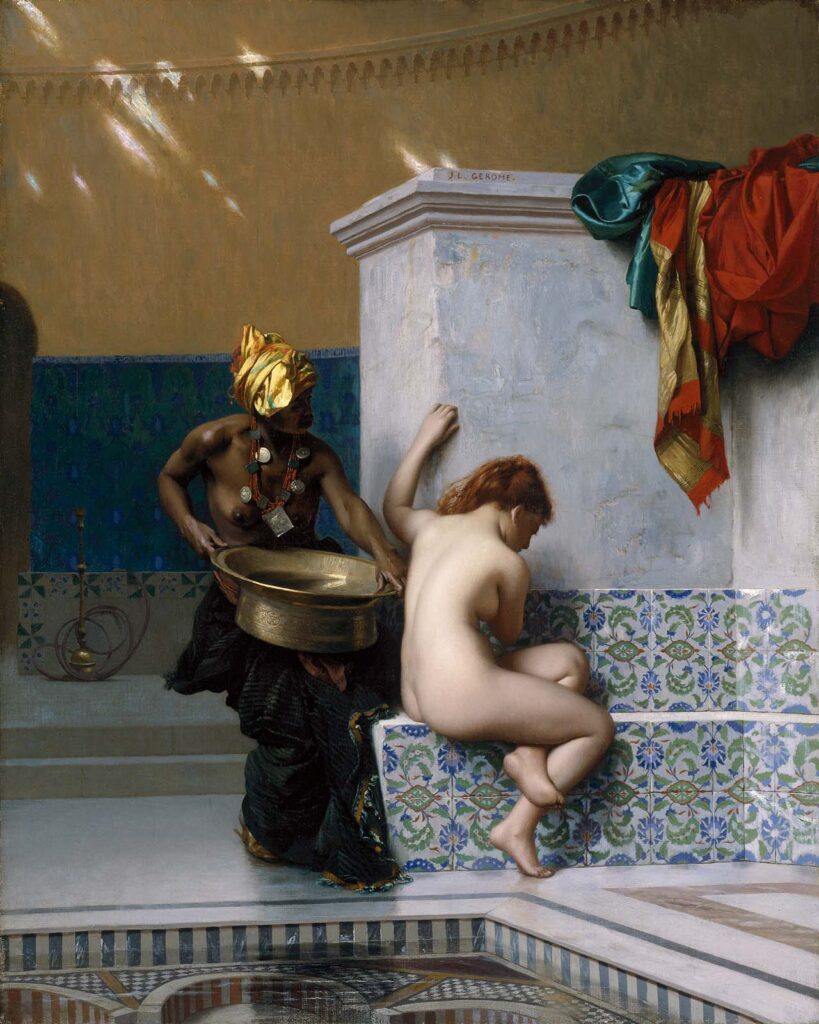

Orientalist painting adapted this pictorial strategy to ‘whiten’ one‘s Whiteness. Particularly in erotic scenes, the Black female servant ought to make her mistress radiate as eye candy for the male White viewer. This is evident for instance in Gérôme‘s Moorish Bath.

Racism in Western Art: Jean-Léon Gérôme, Moorish Bath, 1870, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

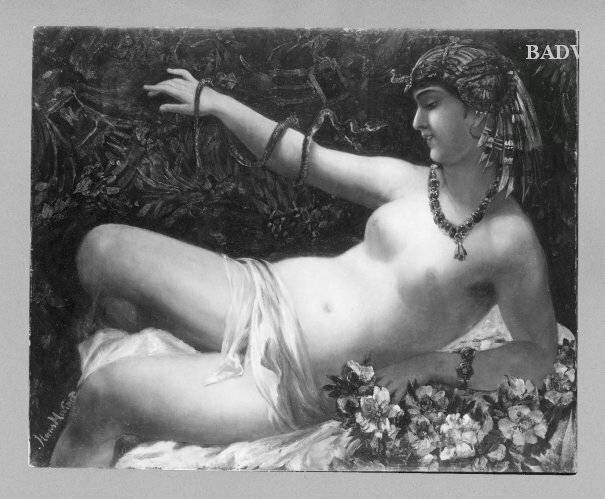

Hans Makart follows this pattern, as the servants‘ dark skin elevates Cleopatra‘s already shining White body. Heinrich Faust‘s painting of Cleopatra incorporates the widespread type in which the Black servant gazes at her mistress.

Racism in Western Art: Heinrich Faust, Cleopatra, 1876, private collection. Christie’s.

This underscores the latter‘s ‘function’ as a passive object that is being looked at. While the Black woman is not the center of attention, she can be characterized as sexually desirable, as we can see in the beauty of the dead servant in Makart‘s painting. But she will always be one step below in the hierarchy to the light-skinned ‘star’ of the artwork. Hans Makart reinforces this distribution of power by presenting the Black women as physically subordinate to Cleopatra.

Racism in Western Art: Hans Makart, The Death of Cleopatra, 1875, New Gallery, Kassel, Germany. Detail.

The queen is enthroned over the servant lying on the floor. Théodore Chassériau‘s harem scenes, for example, depict the Black servants crouching, while the light-skinned woman stands erect.

The more we go through this kind of imagery, the more we become convinced: light-skinned women are displayed as more desirable than dark-skinned women. Even though we can appreciate the aesthetic appeal and technical skills of artworks like Hans Makart‘s Death of Cleopatra, we must acknowledge and confront that they constructed and perpetuated racist stereotypes that still prevail today.