5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

1 June 2023 min Read

Three things we must tell you about this artist: 1. Her transgressive work includes some of the best print-making of the 20th century. 2. She was obsessed with a secret all-male religion called Abakuá. 3. She died tragically aged just 32. We present to you the fascinating story of Cuban artist Belkis Ayón.

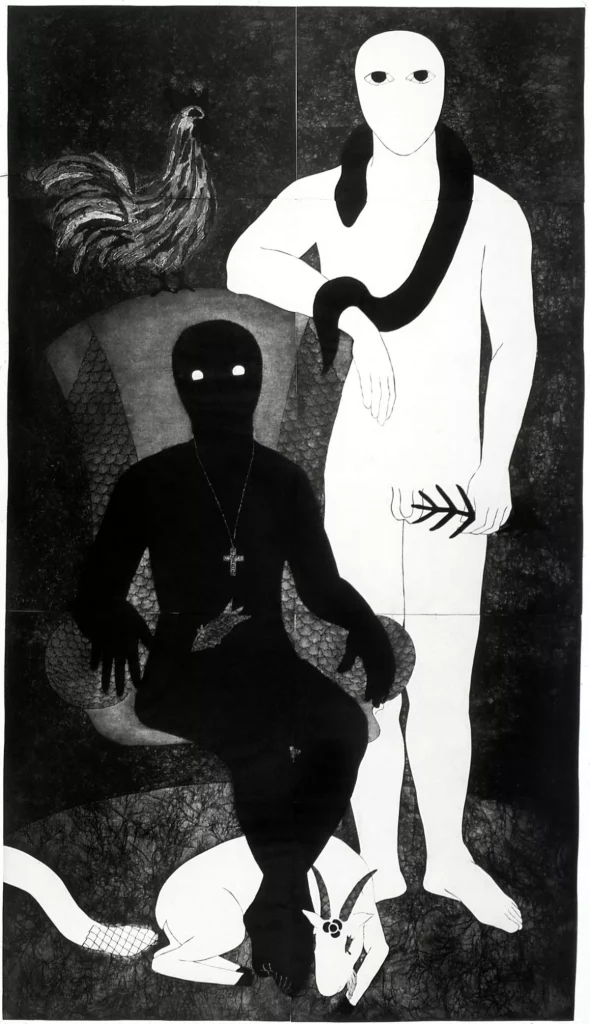

Belkis Ayón, The Consecration II, 1991, The Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

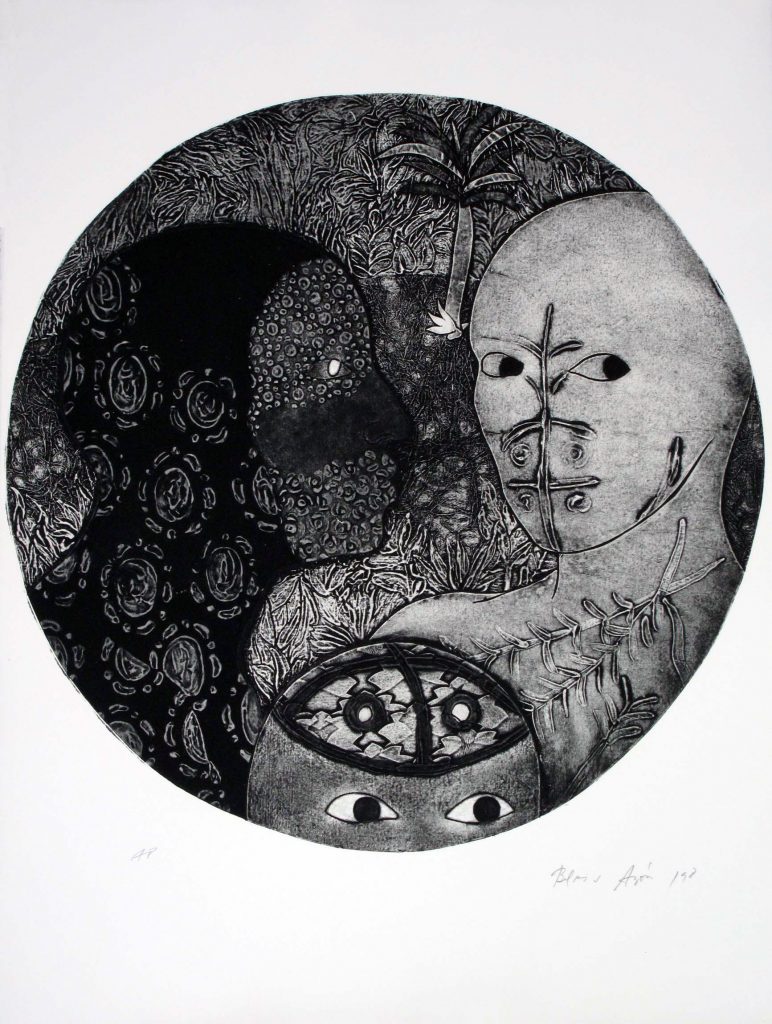

Belkis Ayón was born in 1967 in Havana, Cuba. She produced monumental monochromatic artworks, specializing in the technique of collagraphy. This is a printing process in which materials of various textures are glued to a rigid substrate such as cardboard or wood. Paint or ink is then applied to this plate and pressed onto the paper. Given the severe shortage of art supplies in Cuba, she was often forced to recycle imaginatively. She even used vegetable peelings and paper scraps. She also used a hand-cranked printing press and often carved or embossed prints, to add extra texture.

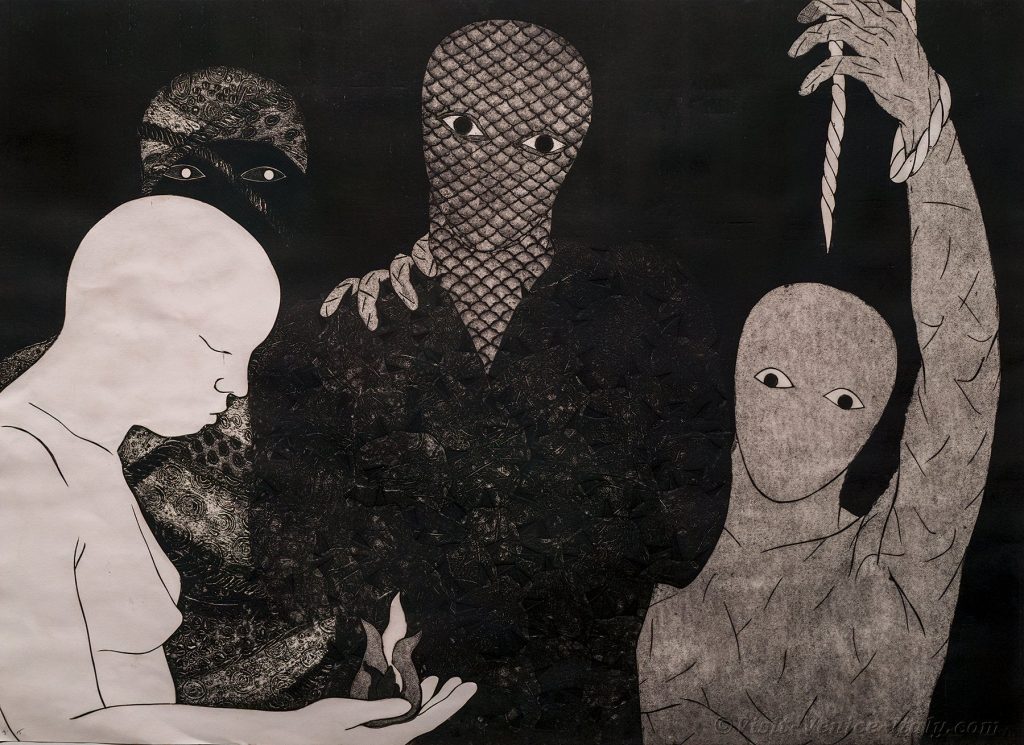

Belkis Ayón, The Consecration I, 1991, Venice Biennale Art Exhibition, 1993, Italy.

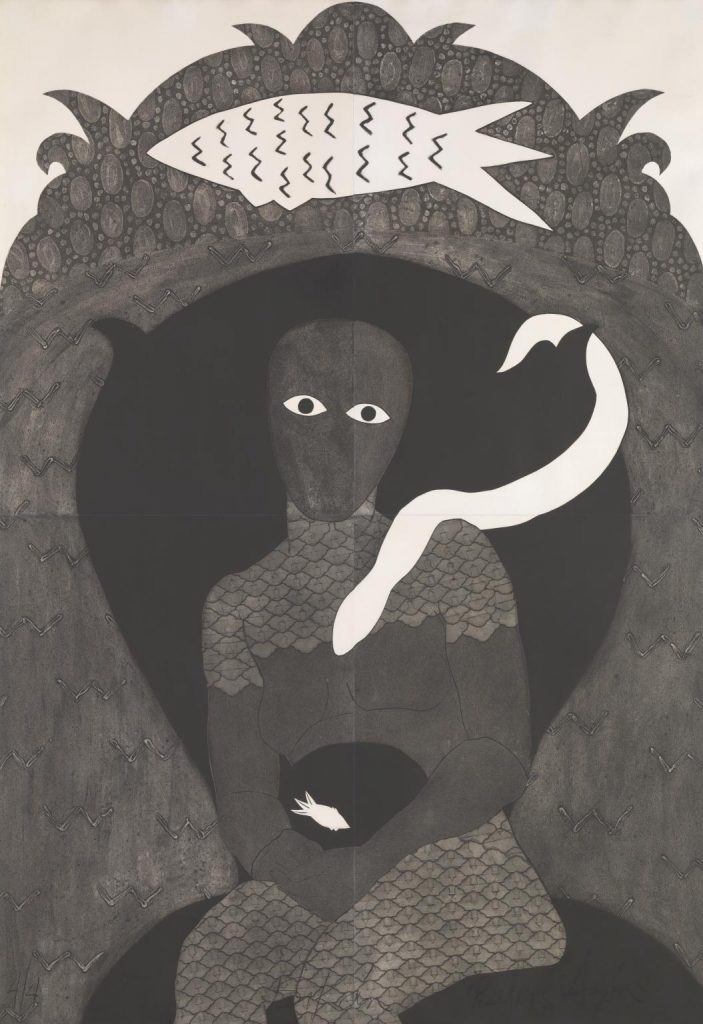

Ayón’s work is highly detailed. Immense technical skills allowed her to create a vast range of forms, textures, and tones in her print-making. Using mostly blacks, whites, and greys, she created ghostly figures with oblong heads, large, empty eyes and often no mouth. These figures stand before abstract, heavily patterned backgrounds.

Belkis Ayón, The Fisherman, 1989, Venice Biennale Art Exhibition, 1993, Italy.

During her brief career, and despite heavy travel restrictions for Cubans, Ayón exhibited across the world in countries such as Canada, the USA, Germany, India, and South America. She was invited to the 1993 Venice Bienalle and had to cycle 20 miles to the airport as drastic fuel shortages in Cuba made transport problematic. Her father cycled behind with her art strapped precariously to his bike. This is a strong and passionate artist who was not going to be left behind!

Belkis Ayón, The Family, 1991, Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Talent was in abundance from a young age. At just five years old, Ayón’s mother enrolled her in an art program at the Máximo Gómez library in Havana. She entered national and international art competitions, winning awards and honors. Aged 19 she became a student of the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana, and when she graduated, she started teaching there.

Belkis Ayón, The Rope and the Fire, 1996, belkisayon.org.

Ayón dedicated herself to exploring the codes, symbols, and tales of the Abakuá. This all-male society was introduced into Cuba in the early 19th century by West African slaves. It operated in stark contrast to the Communist government of Cuba, which took a strong anti-religion position. Ayón was an atheist but was curious about the secretive Abakuá. This was less to do with religion and more to do with how humans choose to mythologize their origins, and how they defend their rules and behaviors. The female characters in Ayón’s work are literally silenced – they have no mouths, as women are not allowed to play any part in Abakuá society.

Belkis Ayón, untitled, 1998, Couturier Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Just as in Christianity, the men of this religious society base their foundational mythology on the idea that a woman’s act of betrayal is the source of sin. For Christians, Eve biting into the apple led to the downfall of mankind. For the Abakuá, it is Princess Sikán, who finds Tanze – a sacred fish that brings peace and great power. Sikán is ordered by her family to remain silent about her discovery of Tanze. But she shares the secret with her lover, who belongs to an enemy tribe. For this, she is executed, and Tanze dies too.

Belkis Ayón, Sikán, 1991, Tate, London, UK.

Princess Sikán, for Ayón, is a key player, the Great Mother Mary, sidelined, sacrificed yet pivotal to the story. Through her works, she melds and mixes Abakuá beliefs with Christian motifs and scenes such as the Last Supper and the Resurrection. Remember Daphne of Greek mythology, who chose eternal silence over sexual assault. Or Philomela in Ovid’s Metamorphoses who is raped and has her tongue cut out to stop her revealing the crime. Throughout art and life, we see the silences imposed on women by religion, misogyny and patriarchy.

These are the things I have inside that I toss out because there are burdens with which you cannot live or drag along. Perhaps that is what my work is about — that after so many years, I realize the disquiet.

Revolución y Cultura magazine, February 1999

In 1999 Ayón ended her own life at home with a gunshot to the head. Why she did it remains a mystery. Was there external involvement? No evidence was found. Her family and friends were shocked and devastated. This great artist died aged just 32.

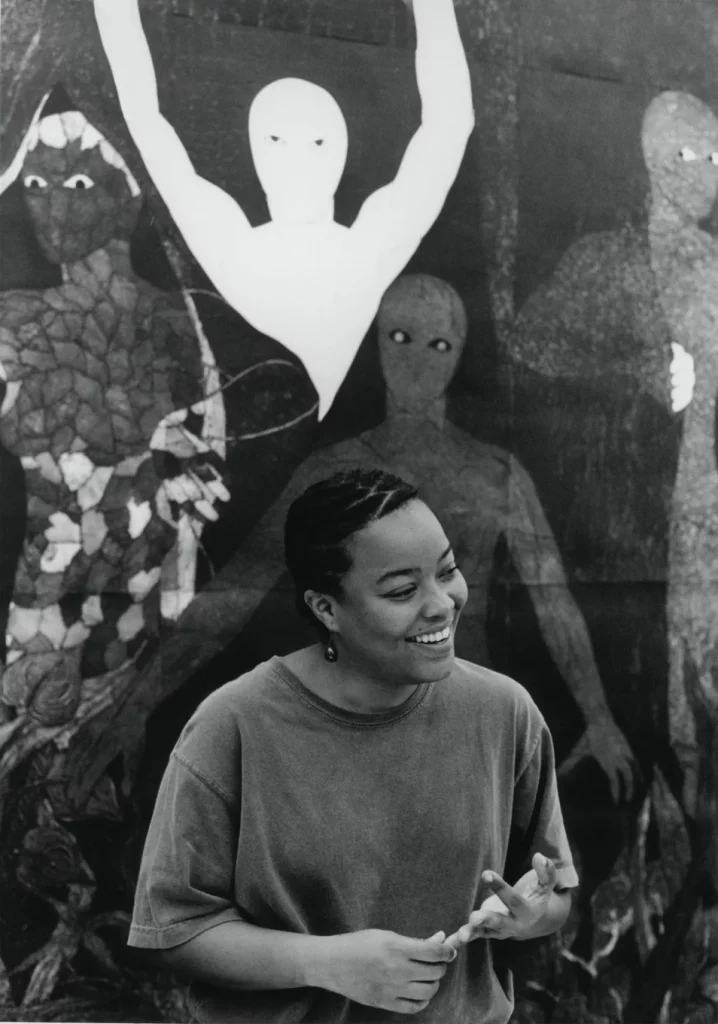

Belkis Ayón at the Havana Galerie, Zurich, August. 23rd, 1999, Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

The beauty of these works is that Ayón, a female artist, gives voice to the silenced female characters. Her rebellious, transgressive art provides hope to us all. She reminds us that the feminine presence is sacred, and is present in all religions and cultures – we have to look for it. Her haunted, silent women speak to us from the art she left behind. Agony, abandonment, physical harm and multiple oppressions are the order of the day for so many women across the globe. Belkis Ayón knew this in her heart. She knew we could not look the other way. In the end, it killed her. We should honor her message and celebrate her legacy.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!