Early Fall, for students around the world, means one thing: back to school, back to writing papers, and exam preparations. For students of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), it means back to Ciudad Universitaria, the beautiful complex of modernist buildings, planned by a group of architects, among whom were Enrique del Moral, Mario Pani, Teodoro González de León, and Luis Barragan.

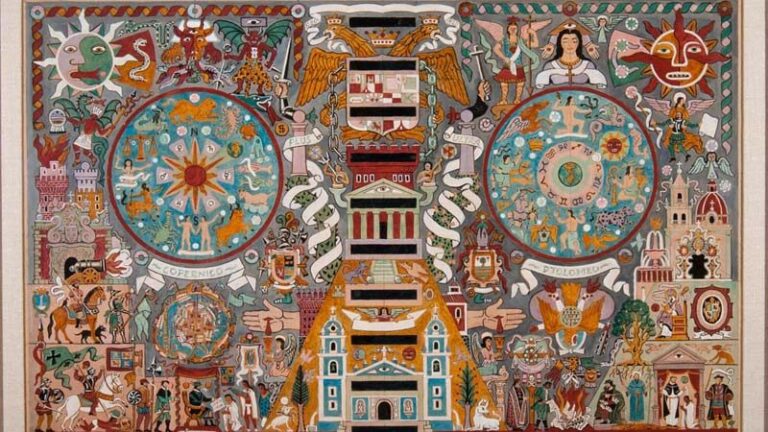

Of course, they also return to the Central Library which dominates the campus, as it is erected in its center. The library is not only admired because of its architectural design, but because of the enormous mural titled Historical representation of culture, created by Juan O’Gorman. The work covers all four walls of the building. It is the largest mural in the world, made of natural stones, encountered only in Mexico.

Central Library of the National Autonomous University of Mexico

More than half a century ago, all the information was held not on the internet but in libraries. They were the vassals who held the knowledge acquired through centuries; they were temples to science and discovery. So when the Mexican government in the late 1940s decided to finance the new campus for its largest and oldest university, it also wanted to build the biggest library, which would preserve millions of books and academic journals collected for centuries. The task of designing it was given to three prominent architects: Juan O’Gorman, author of Frida and Diego, Casa Azul in Coyoacan, Gustavo Saavedra and Juan Martinez de Velasco. They created a project that specified a ten floor book depository with a windowless façade. The construction work started in 1952 and it opened its doors to students in April 1956.

Mosaic Mural

The total surface of the library is 16,000 square meters. The mural that covers its façade is completely constructed with natural stones and other materials picked and gathered all over Mexico by O’Gorman himself and his team. The decisive factor in choosing stones was their resistance to weather conditions. Only 12 colors are used to create highly symbolic scenes from the history and mythology of Mexico. 15 construction workers had to manually crush the larger blocks into 2 cm or 4 cm pieces, because the project couldn’t effort the professional machine to do it. Later elements were assembled on a small block of 1 m², which were the fundamental building blocks of the whole picture.

The composition of the north and south wall is symmetric. It gives the illusion that the left and right sides mirror each other, but after a closer look, we can see the difference.

The result was named by O’Gorman Historical representation of culture. The huge mural combines symbols and scenes from Mexico’s past and present. It juxtaposes pre-Columbian and modern styles of visual narration. It tells a story in four chapters of the cultural transformation that happened in Mexico over the centuries. It depicts the deities and legendary warriors, code of arms, artifacts, places real and imaginary from the prehistoric times of Mayas and Mexicas, through the colonial period of viceroyalty of New Spain, across the tumultuous period of the Independence (after 1820) and the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917), to the last stage, when Mexico is ruled by reason and science.

It must have been a truly challenging endeavour to create such an enormous work of art with non-traditional materials, in a collaborative way where the artist worked with a group of masons and construction workers, under pressure of time with scarce resources. The result is impressive, consistent, symmetrical, and evenly organized.

South Façade

The south façade shows the contact between two civilizations. In the center there is a two headed eagle, a symbol of Habsburg dynasty with the dates 1521-1820, that is the period of Spanish domination. Below the bird, there is a catholic colonial church embedded into a pyramid.

On the left side, the mural shows the religious colonization, the coercive Christianization of the native peoples.

On the right side the military conquest is depicted with the Tenochtitlan invaded by Hernán Cortés’ troops.

The composition is organized around two circles that symbolize the earth; they are inscribed with the names of two trailblazing astronomers, Ptolemy and Copernicus, whose discoveries allowed Columbus to undertake the voyage to the west.

The Latin inscription Plus ultra, which is visible in the middle of the mosaic, refers to the Greek myth about Hercules, who put two columns in Gibraltar to mark the end of the world known to humans. As the Spaniards conquered Mexico, the end shifted to the newly acquired colony.

North Façade

The north side of the mural is designed to show the Maya/Aztec pantheon of gods and the core beliefs of the indigenous peoples. Above everything, there are two feathered serpents – symbol of the Quatzalcotl – god of wind, air, and learning. On the left side there is Tonatiuh – god of the sun, on the right side Mictlāntēuctli – god of the underworld and death.

In the highest part is Tlaloc, who the Mayans believed was the god of water overlooking the cosmos, from whom the waters spring. Below him, there is Tlazolteotl, the “goddess of childbirth”.

The whole surface is divided by the water canals that wash the Tenochtitlan, capital city with the cactus (nopal) and the eagle with the serpent in its beak. These currents also delineate the vicinity towns: Coyoacán, Churubusco, Iztapalapa, Xochimilco, Azcapotzalco and Tacuba. According to the origin myth of the Mexicas (the tribe popularly known as Aztecs), they migrated from Aztlan (land in today’s New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas) and found a new motherland in the Valley of Mexico, in a place where an eagle sitting on a cactus devouring a snake was encountered. They created Tenochtitlan.

Two big figures, on the right and left of the work, in very elaborate costumes, are tlatoani, two kings of Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

The decoration at the bottom shows a set of warriors covered with animal skins and armed with macans and chimalis (shields). The whole visual language is taken straight from the Maya and Aztec codices.

East Façade

Source: bibliotecacentral.unam.mx

The much smaller western wall of the building depicts modernity. Mexico is shown here as a developing country after the violent revolution that changed its social structure and after the agrarian reform that redistributed the land to the campesinos (peasant farmers). The mural shows here industrialization (factories) and urbanization (city infrastructure). But still these symbols of modernity are mixed with the popular and indigenous cultures.

In the upper center, the Aztec warrior Cuauhtémoc reappears, together with the figure of the dove of peace on his chest, integrated into the representation of the atom and fire, creator and destroyer. They overlook the current state of affairs in the new Mexico.

West Façade

The last part is a celebration of the university with its emblem in the middle of the whole composition. The university is presented here as an institution that nurtures society and the country, maintaining heritage and driving progress.

Source: bibliotecacentral.unam.mx

The Central Library keeps the whole world of knowledge yet acquired in one place. It is a unique universe where all visions, theories, and sciences live next to each other as equals.

The O’Gorman mural that envelops the building also represents a similar cosmovision of continuity and conjunction across centuries of different cultures. Here, past is present; myths are as real as historic facts; symbols are as important as people.