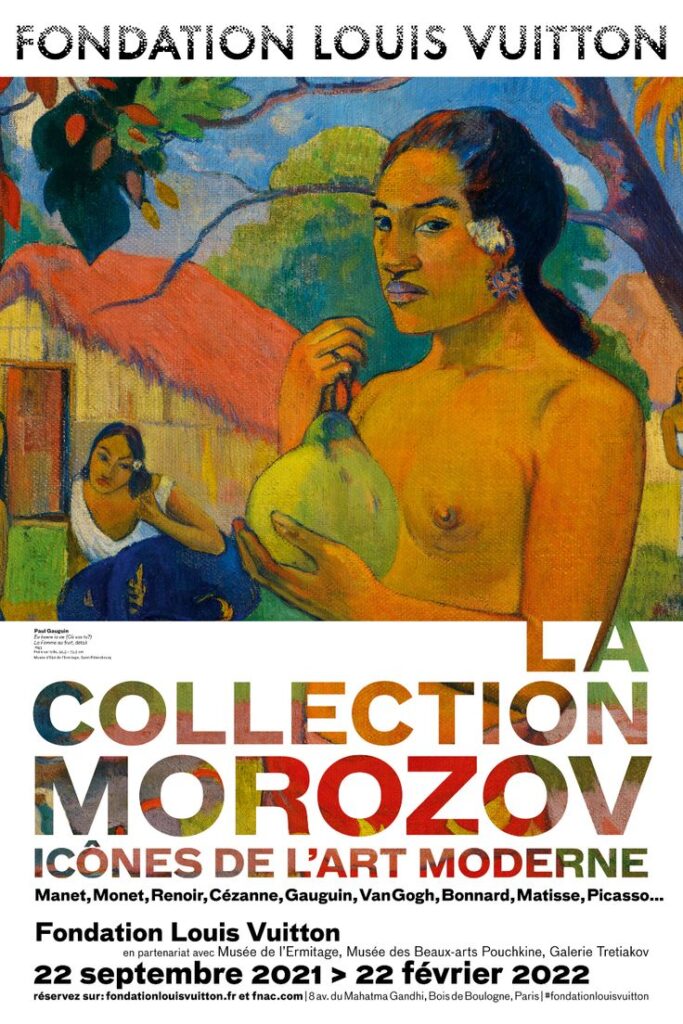

Under the careful direction of Anne Baldassari (former head of the Picasso Museum), the show is a sequel to a 2016 exhibition that similarly unveiled and reunited another Russian collection—that of Sergei Shchukin—to great critical and financial success. Baldassari refers to the two shows as a diptyque, completing and contextualizing each other. Sergei Shchukin was an important figure for the Morozovs, who saw him as a friend and collecting mentor.

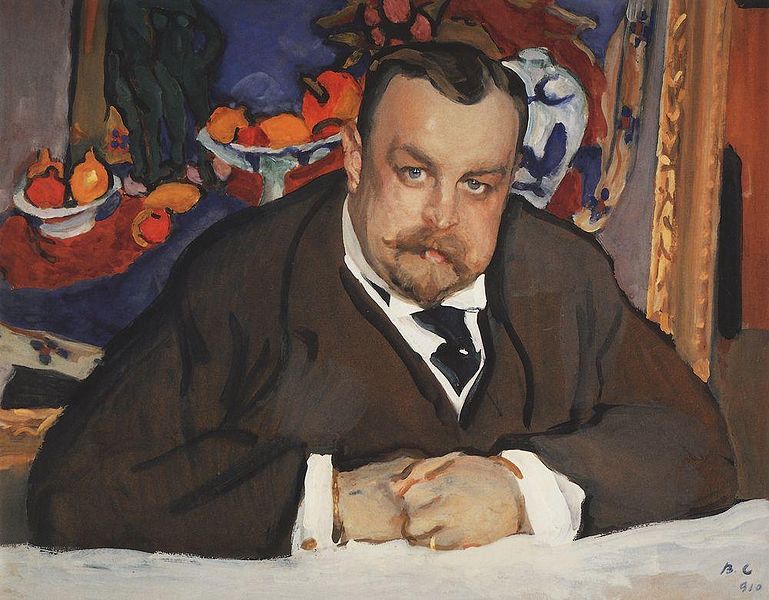

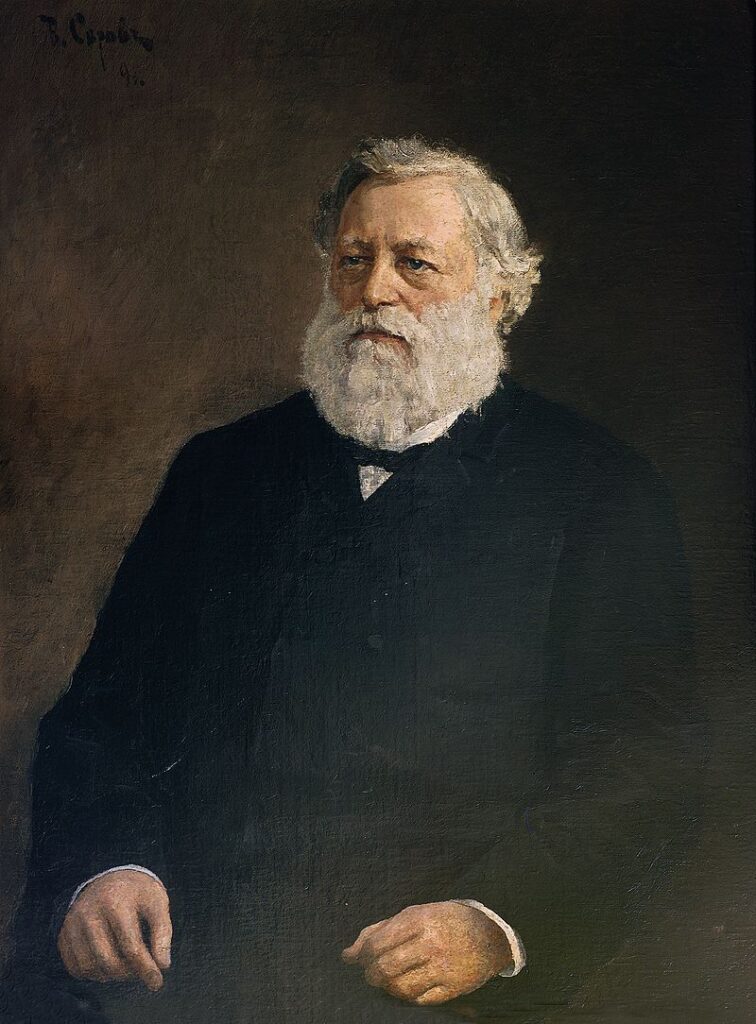

The exhibition begins in the basement and winds its way upwards through Frank Gehry’s iconic glass and wood structure. The rooms are organized thematically. The first is a portrait gallery, in which one becomes acquainted with the Morozov brothers and their circle. The works in this room are all by Russian painters, giving the exhibition a strong departure point by demonstrating what the brothers bought from their own country. Especially eye-catching are the portraits by Valentin Serov.

The following rooms are dedicated to different themes or single artists. An especially special room is devoted to the close relationship the Morozov’s had with Pierre Bonnard, from whom Ivan commissioned murals for his home.

Another room focusses on Impressionism, both Russian and French. In the exhibition catalogue, President Vladimir Putin describes the show as a “symbolic reconciliation” of Russia and France. Whether this is true or not is beside the point, though the two nations did have to carefully cooperate in order to pull this off. What seems more important is the demonstration of the clear links between Russian and French art in the 19th and 20th centuries, demonstrated in the ingenious choices to hang artists like Konstantin Korovin and Claude Monet, Mkhail Larionov and Paul Cezanne, or Pablo Picasso and Natalia Goncharova, side by side.

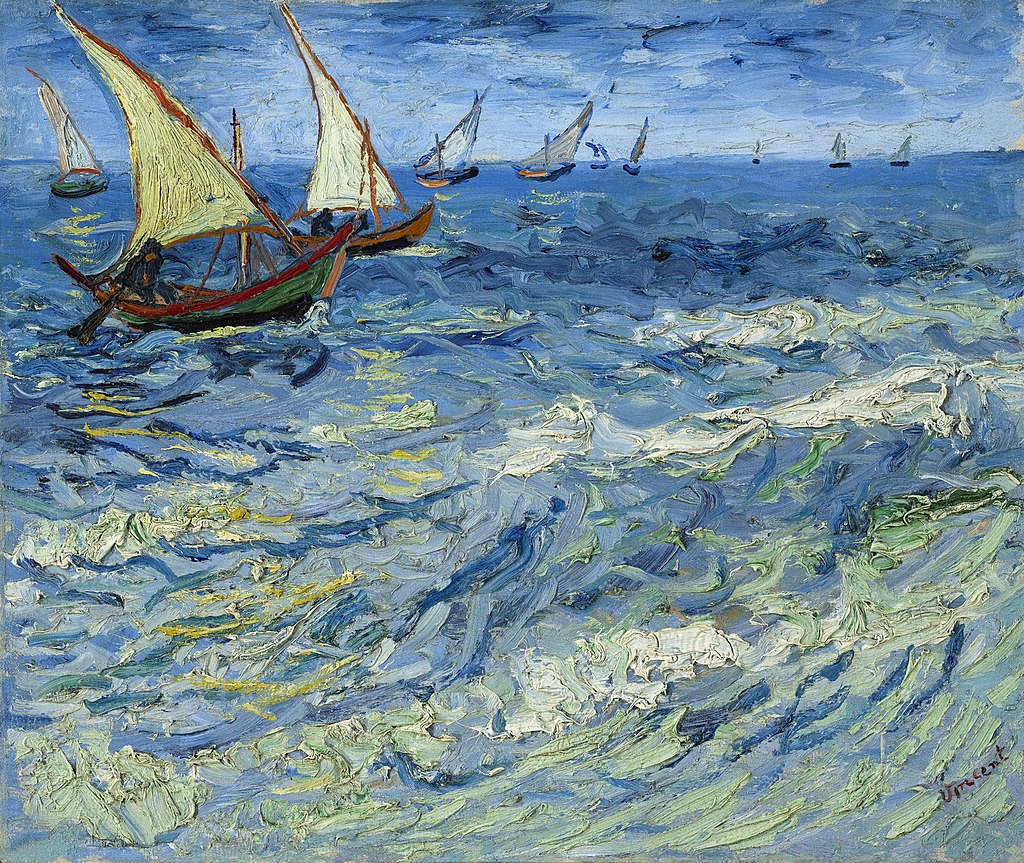

The rooms unfold, each one seemingly more impressive than the last. Among the works by Paul Gauguin is Café d’Arles, painted as a response to Van Gogh’s Le Café de nuit, which used to be in the Morozov collection before it was sold by the Soviet state in the 1930s (the painting is now at the Yale University Art Gallery). Nearby are several Cezanne landscapes and Picasso’s Portrait of Ambroise Vollard. Another superb Picasso, Girl on a Ball is in playful context with Ilya Mashkov’s Self Portrait and Portrait of Pyotr Konchalovsky.

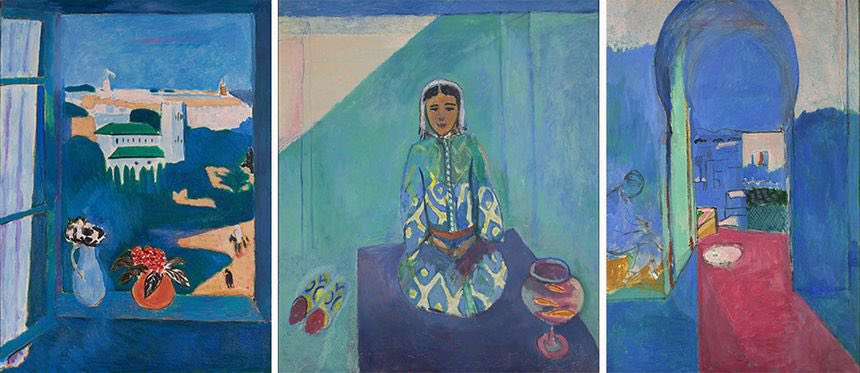

A highlight of the Henri Matisse room was the artist’s Moroccan triptyque commissioned by Ivan, featuring sun-drenched streets and azure skies. Nearby are several of the artist’s signature still lifes and one particularity intriguing painting could nearly be mistaken for a Chardin.

Time and again the exhibition gives the surreal feeling of being inside an art history textbook; recognizable masterpieces by Picasso, Matisse, or Gauguin, or Cezanne are literally around every corner. This risks overwhelming the viewer, but thanks to thoughtful curation led by Baldassari, works are hung on blank walls and spread out so each piece has adequate room to breathe.

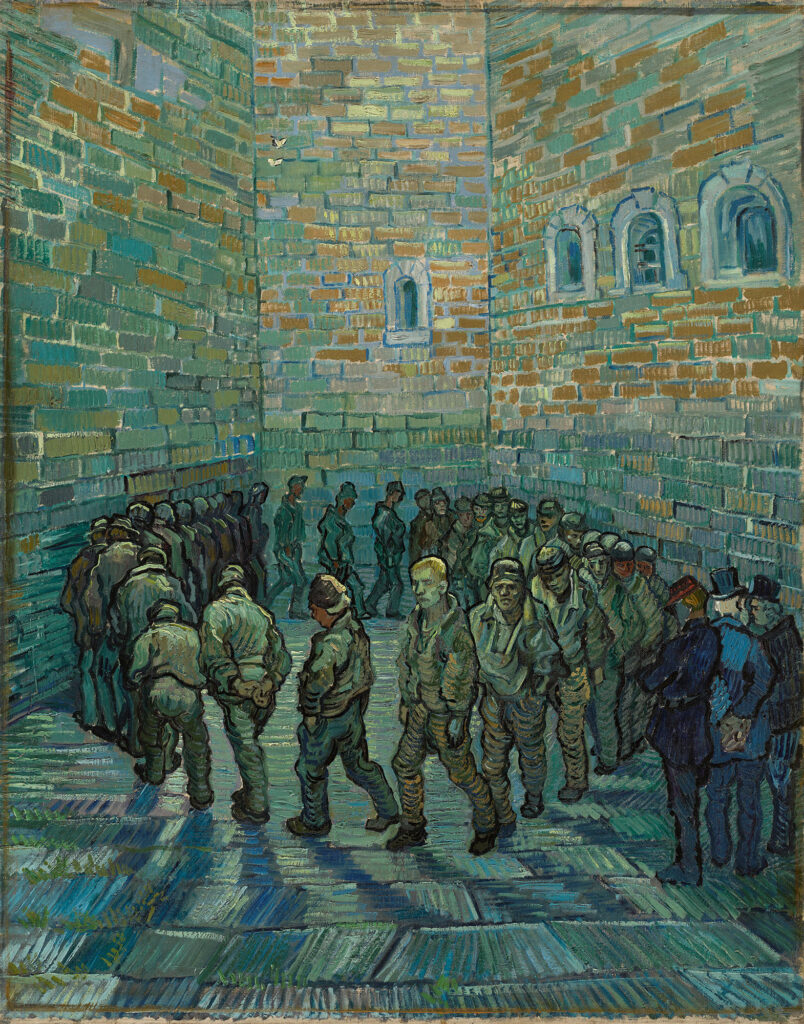

This foresight is best demonstrated in the choice to place Vincent van Gogh’s Prisoners Exercising on its own. In a small, circular room with dimmed lighting, the viewers’ experience verges on meditative, while also referencing the claustrophobic ambiance of the painting itself.

The exhibition ends on a powerful note with a reconstruction of Ivan’s music room, featuring beautifully restored panels by Maurice Denis. Music plays softly in the background, and you almost expect to hear people speaking Russian instead of French.

This blockbuster exhibition is the product of dedicated curatorial work, international diplomacy, and financial backing from the third richest man in the world. Due to or perhaps despite all this, it succeeds.

The Morozov Collection. Icons of Modern Art runs through April 3rd, find more information and book tickets here.