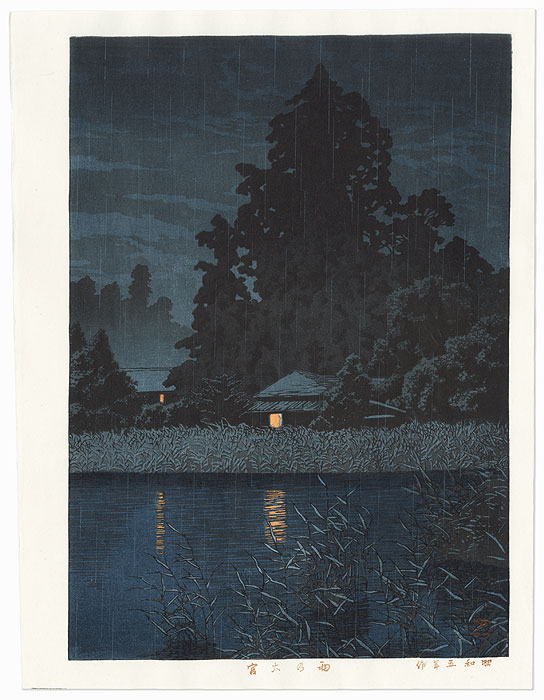

Kawase gained international acclaim in his long career of over 40 years. Unfortunately, a bulk of Kawase’s works were destroyed when a devastating earthquake in 1923 destroyed his studio. However, several works have been preserved in museums and private collections all over the world. In 1956, in acknowledgement of his outstanding career, Kawase was named a Living National Treasure by the Japanese Government.

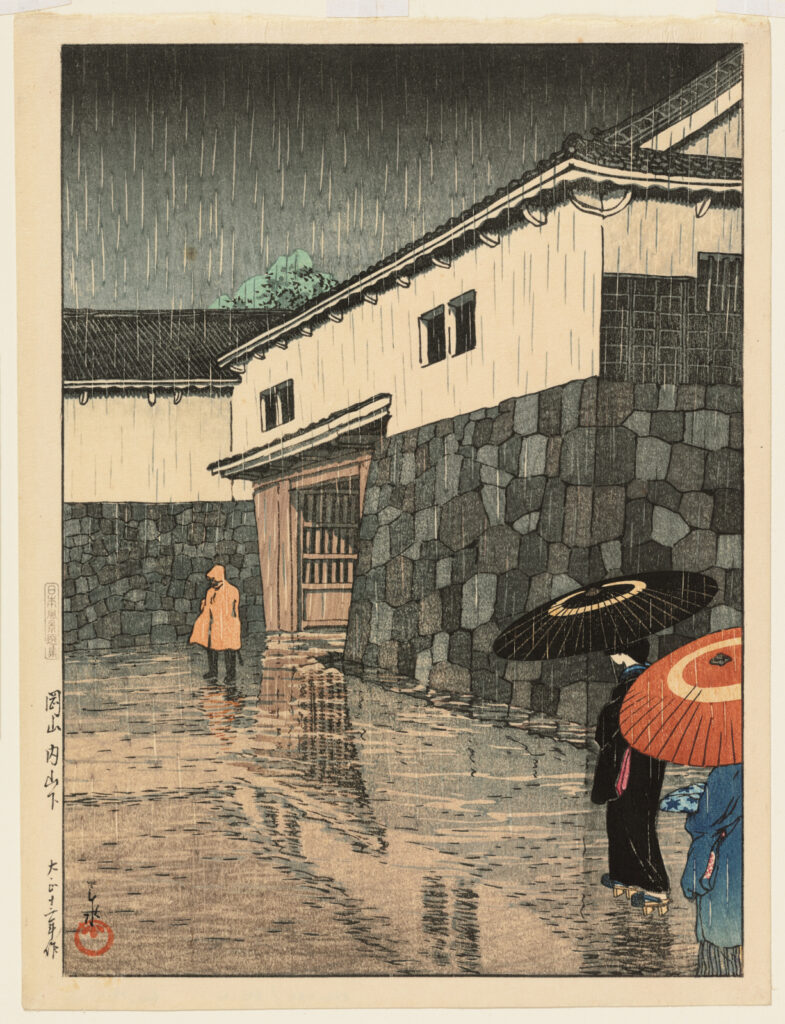

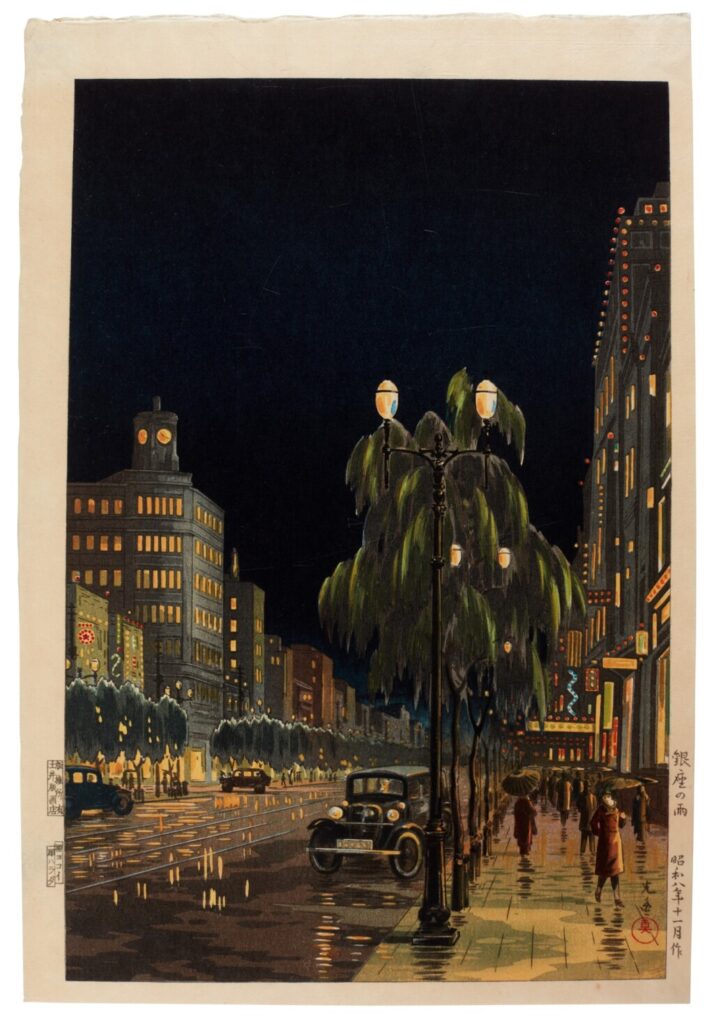

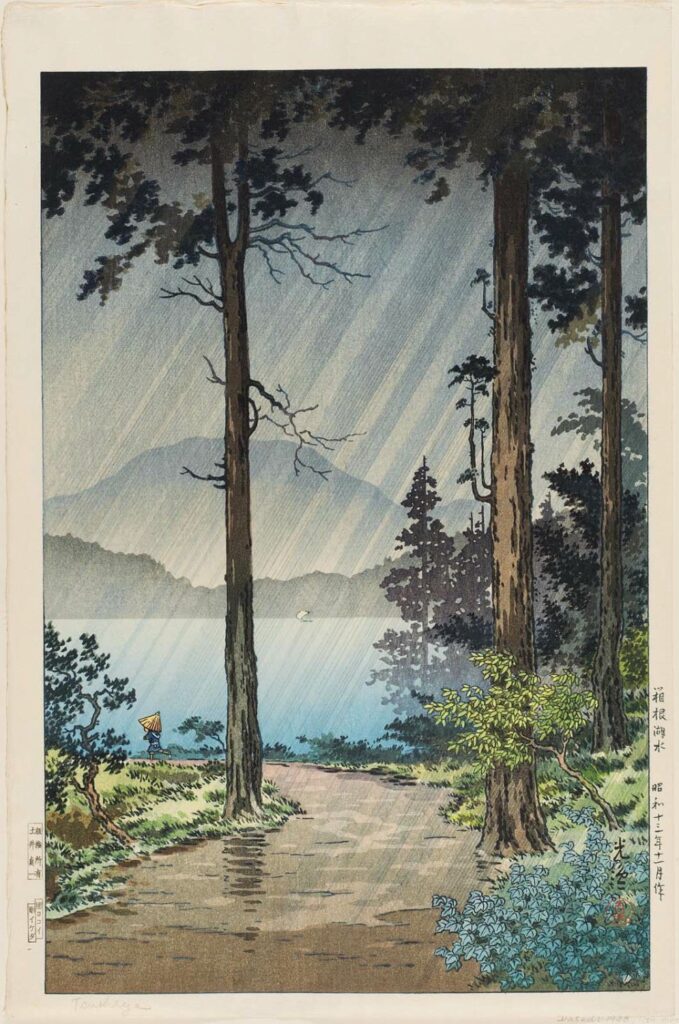

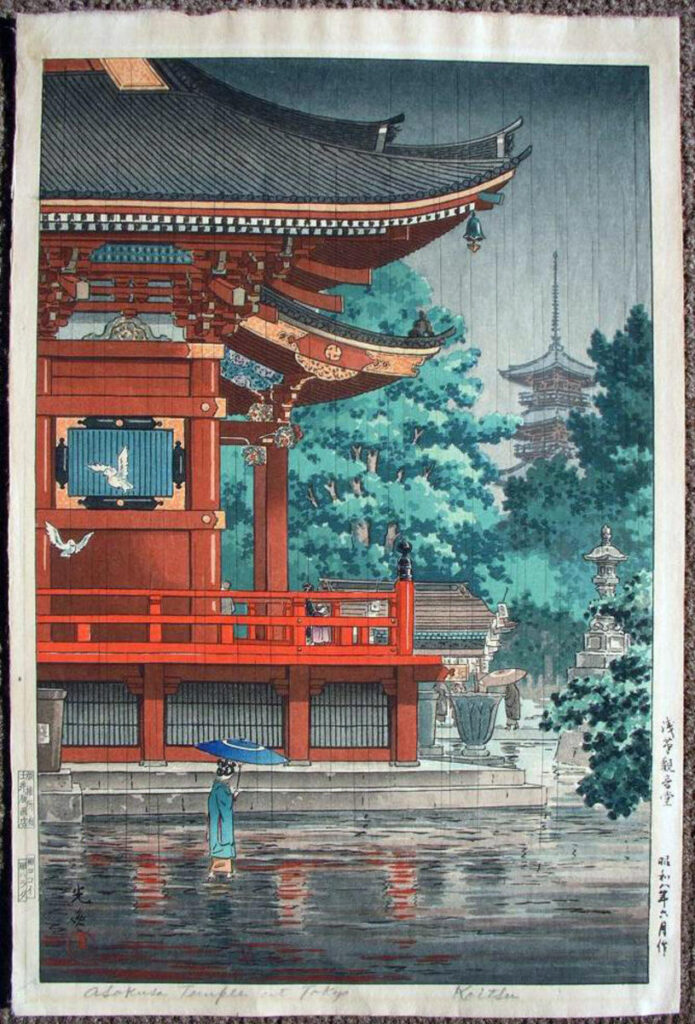

Tsuchiya Koitsu

Tsuchiya Koitsu (1870–1949) was apprenticed to an ukiyo-e master Kobayashi Kiyochika for 19 long years where he studied the art of woodblock printing. His initial works were depictions of the Sino-Japanese war, and he also worked as a lithographer. A chance meeting with the publisher Watanabe Shozaburo in 1931 changed the course of his career, and he turned his focus to landscape prints depicted in the shin-hanga style.