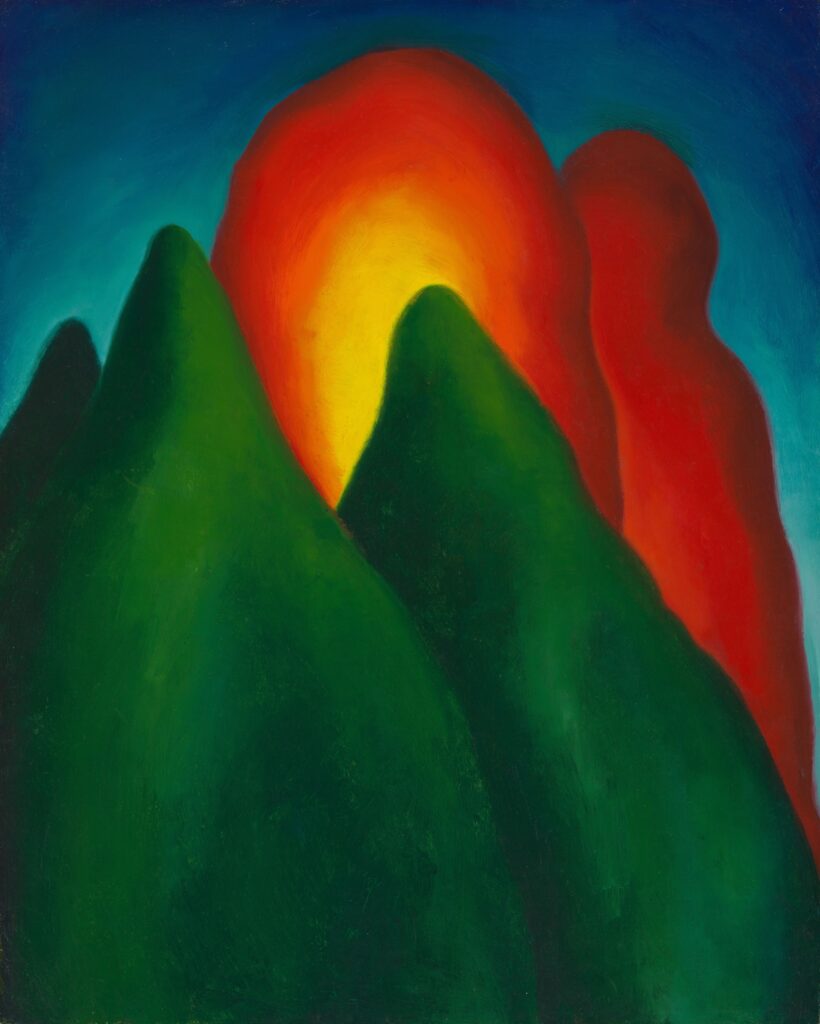

Georgia O’Keeffe worked hard to achieve the degree of ingenuity she found in Dow’s art. As a result, the abstractions of nature that she created demonstrate traits that characterize the majority of her oeuvre. Such traits include simplified, smoother textures, vibrant colors, or when color is absent, the striking contrast of values.

Throughout her career, O’Keeffe successfully produced art that maintains its newness despite the time that has passed since its creation. One cannot deny the profoundly original perspectives in her paintings, whether it be an abstract close-up of a flower or a sweeping desert landscape. It is no wonder that her art stood apart from others when Alfred Stieglitz first beheld it.

Alfred Stieglitz: Before Georgia

While Georgia O’Keeffe endeavored to form a unique artistic voice in her artwork, Alfred Stieglitz had long been established as a respected photographer and promoter of art in New York City.

Born in New Jersey, Stieglitz studied a variety of subjects before focusing on artistic pursuits. Eventually, he became one of the most prominent advocates for photography as an art form shortly after its invention. He was also a key contributor to modern art’s development. It was through this work that he would eventually meet Georgia O’Keeffe.

By the time Stieglitz reached his early fifties, he was a respected authority on art and photography. His founding of Gallery 291, a sort of Salon des Refusés, for those bold artists whose art was rejected for display elsewhere, had cemented his status as an artist open to change and the evolution of art beyond what was known. He was also a groundbreaking photographer in his own right, evidenced by his creation of the Photo-Secessionists, a group of photographers determined to establish photography as a serious art form. His publication, the magazine Camera Work reached subscribers across the country.

When their lives converged, Stieglitz was over 20 years O’Keeffe’s senior. Thus, he had both the privilege of time and being a man, which lent to his success. O’Keeffe had established herself as an art educator, but her path to discovery as an artist began with Stieglitz.

An Artist Discovered

When Georgia O’Keeffe sent her charcoal drawings that represented her departure from realism to New York, it set in motion her discovery by the man who would be her chief promoter and, later, her husband. O’Keeffe also became a significant contributor to the photography of Stieglitz as his primary muse and model for the latter half of his career as the subject of over 300 photographs.

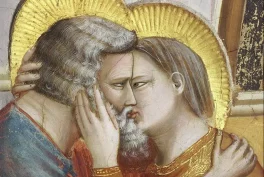

When Stieglitz saw O’Keeffe’s modernist drawings, he immediately displayed them in his Gallery 291 without the artist’s permission. Soon after, O’Keeffe went to New York to see her works in the gallery and to make Stieglitz’s acquaintance. Immediately, the two recognized that they were irrevocably drawn to one another.

The artists formed a unique correspondence where they bared their souls in a way that, as they acknowledged, they had never done before. It was inevitable that the letters would become unsustainable for the deep connection felt between the passionate artists, and thus, O’Keeffe moved to New York to work. This would allow her to be close to Stieglitz, who eventually became her mentor and, soon after, her lover.

The Artists’ Love Affair

Despite Stieglitz’s marriage, and completely disregarding the many years’ difference between them, O’Keeffe and Stieglitz found themselves swept into a tumultuous relationship that escalated quickly in passion and artistic productivity. It is difficult to view the photographs Stieglitz took of O’Keeffe without feeling somewhat intrusive, for the artist’s many portraits present O’Keeffe as overwhelmingly vulnerable. We see her through the eyes of the man who worshiped her as a woman and artist. This reverent attitude may be seen through his fascination with photographing O’Keeffe’s tools of creation, her deft hands.

Mutual Influence

Studying the intricacies of the relationship between this artistic couple provides a new lens through which to observe the art they created. Without Stieglitz, it is impossible to know whether O’Keeffe’s art would have received the acclaim that it has rightfully done to this day. Equally, it is difficult to imagine how Stieglitz’s career would have achieved the longevity that it has without the striking photographs of his muse and lover, her powerful personality, and her sensational talent.

Though the artists’ love perhaps burned too bright to last through their lives, they certainly depended upon one another to become artistic icons. This is how the modernist artists of their day viewed them, as well as the many, many artists whom they have influenced up to the present. As O’Keeffe grew in independence and leaned into her identity in the deserts of New Mexico, Stieglitz remained her confidante until his death.

To study one of these artists without the other is to do an injustice to the intertwining of their artistic and personal lives. One thing is present through all their art from the time they knew each other: a deep, abiding passion for the continual exploration of themselves through art and the continued, necessary support they provided each other.