5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Not every Orientalist painter journeyed to the Orient or the Levant to observe and interact with the socio-cultural fabric they intended to portray in their works. Some merely relied on catalogues, enquiries, and, of course, on their imagination. The few who were able to venture eastward achieved this in often a constricted fashion in terms of time and place. These circumstances, combined with the colonial spirit of the 19th century, led to various intentional and unintentional problematic representations. Of course, there were also Orientalists whose depictions were usually factual and Theodoros Rallis, a Greek painter who was born in Istanbul (then Constantinople), was one of them.

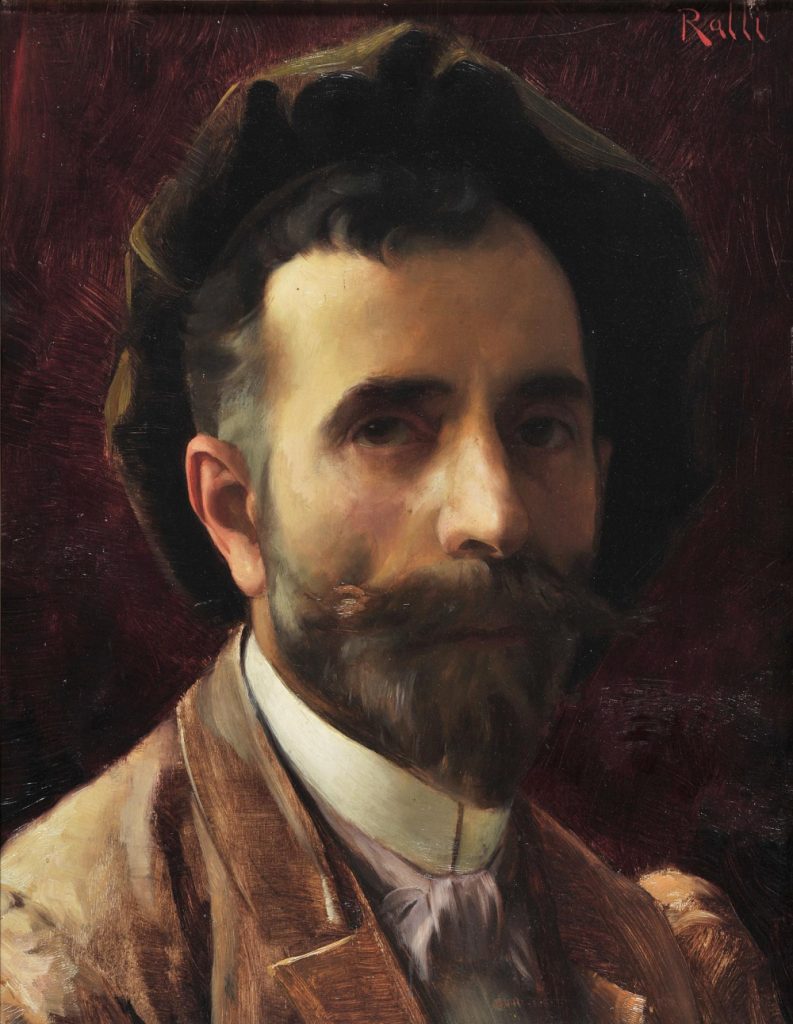

Theodoros Rallis, Self Portrait, 19th century, National Gallery of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Theodoros Rallis was born in 1852 in Istanbul, where the East and the West converge harmonically in every aspect possible. Although he called this famed cosmopolitan city his home, his wealthy and well-known family was originally from the island of Chios. The details regarding why his family moved to Istanbul in the first place and why Rallis left the city at an early age are not clear. Did his family move to Istanbul right after the Chios massacre committed by Ottoman rule? Did the Rallis family intentionally keep their sons away from Istanbul because of the increasing intolerance toward Greeks? These are very well possible scenarios that one can merely speculate in the light of historical events within the region.

Theodoros Rallis posing in his studio, 1880s, Paris, France. Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

Rallis initially set out to work in a family business in London, but after a short while, he had a change of heart and he became fully aware of his passion for art. He permanently moved to Paris. Whether it was directly due to the patronage of Bavarian Prince, Otto, or his skills to demonstrate what he could create, Rallis was admitted to one of the École des Beaux-Arts. During his studies, he had the chance to become a pupil of renowned French painter and sculptor Jean-Léon Gérôme. As one of the most significant painters of the 19th century, Gérôme was a mentor to many artists. He left his mark on painters all around the world such as Osman Hamdi Bey and Hosui Yamamoto.

Theodoros Rallis, Shepherdess, 19th century, National Gallery of Athens, Athens, Greece.

By embracing a manner that homogenizes Academism with an Orientalist perspective, Rallis created fascinating works. In a short period, the circles in Paris began to notice him. His works were first exhibited in the Salon des Refusés and, from 1875 onwards, he participated in the official Salons which were official art exhibitions organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts at the time. Throughout his career, he received multiple medals and recognitions both in France and Greece. He often traveled to the East and visited various countries at different times. Rallis also had his studio in Cairo, Egypt, where he usually spent his winters and devoted himself to internalizing the way that the people of this vast region lived.

Theodoros Rallis, The Captive (Turkish Plunder), 19th century, private collection. Artvee.

A significant portion of Rallis’ works is privately owned. These pieces were sold via mediums such as Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Bonhams. For example, one of his works— titled The Captive (Turkish Plunder)— was sold for 737,300 GBP in 2007 which is the most paid work of Rallis to date. This spectacular painting has a plethora of symbolism in it; through a captured Greek woman, Rallis is portraying what was lost to Turks and how they treat the intellectual, historical, and cultural heritage of the Greeks. Luckily, not all his paintings are privately owned. The National Art Gallery located in Athens, Greece, is currently the best place to see Rallis’ works.

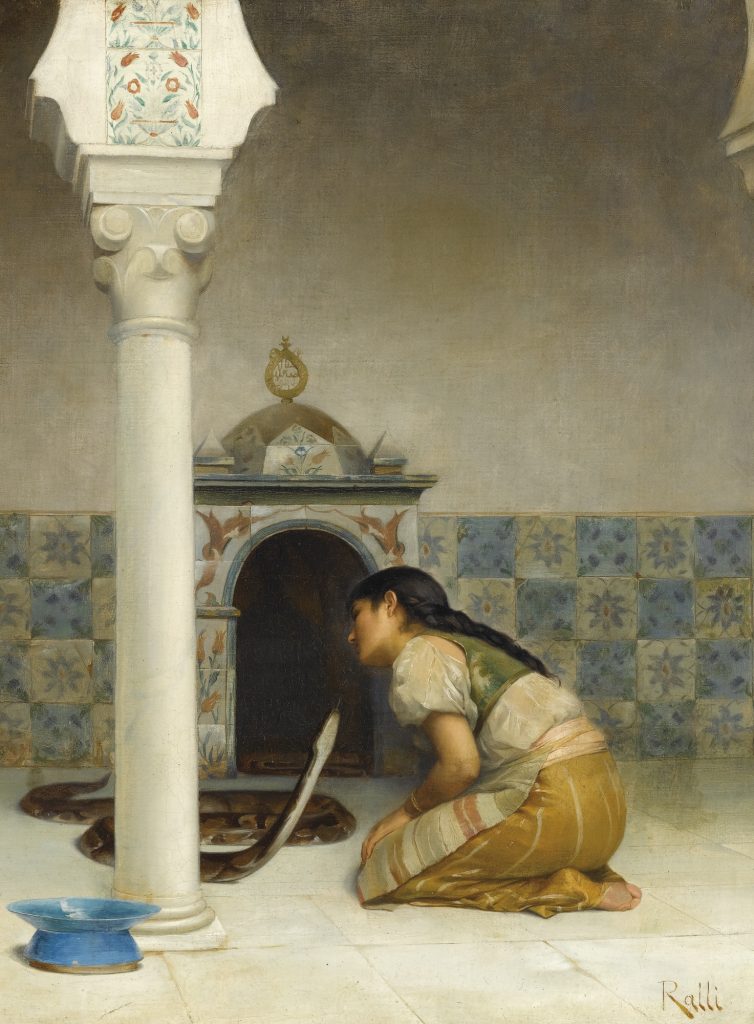

Theodoros Rallis, Snake Charmer in the Harem, 1882. Twitter.

What sort of artistic characteristics separate Rallis from other Orientalists, you may ask. The answer is hidden in his adoption of a style that relies on genuine interpretation. We rarely see cultural distortion and fetishization in his portrayals. For instance, you don’t see a Turkish bath interpretation like this of Ingres—who never set foot in any of the countries located in the East—where 24 entirely naked women hedonistically enjoy their time in a small Turkish bath. This kind of composition, combined with the circular format of the piece, doesn’t present anything to the viewer other than a Frenchman’s wet dream.

Theodoros Rallis, Girl Sitting On a Stone Wall, private collection. MutualArt.

We do encounter sexual themes and nakedness in Rallis’ works where the subject within them is often a woman but these themes emerge aesthetically in a more subtle and naïve way. He preferred to portray ordinary people in their daily routines instead of historically important figures and their achievements. For him, a woman who is smoking in front of her house while contemplating, a girl who is hand-spinning wool into yarn on a roof, and a child who fell asleep in a local church after a busy ceremony formed what art was about.

Theodoros Rallis, Turkish Woman Smoking, 19th century. Artvee.

Every artist tells a story through their art. Within an act of storytelling, the artist may choose to rely on canonical figures or settings that are deeply rooted in our literary traditions, for conveying an idea through already existing and detailed subjects can certainly be convenient. For instance, which literary figure can be more fitting than Achilles when it comes to expressing the emotion of rage on a canvas? We do not see this kind of pattern in Rallis’ works. He conveyed his emotions and ideas through real subjects from life itself and, yet, these real subjects that he encountered throughout his life were more than enough to tell a captivating story.

Theodoros Rallis, The Prisoner, circa 1909, National Gallery of Athens, Athens, Greece.

This is one of my favorite pieces of Rallis where we catch a glimpse of his mastery in storytelling. We see a bearded gentleman with a sorrowful stare who is in prison. He is holding tightly onto the woman’s hands with his left hand that has a ring on it. He is most likely the husband and seems like he just uttered an impactful sentence to the woman. However, the woman seems deep in her thoughts and unresponsive. It feels like this is not one of her usual visits. This time, she came to say farewell but didn’t really know how to word this news. By her right foot, we see an old bag alongside a bottle. It seems that she is ready for the road ahead which the husband doesn’t know of.

Theodoros Rallis, Flirtation, 19th century, National Gallery of Athens, Athens, Greece.

In another instance, we encounter another couple who is in a much more fortunate state than the previous ones. The posture of the man is very self-confident and decided. It seems like he is awaiting or demanding an answer from this beautiful woman. She is looking at the floor and seems both shy and contemplative. In my imagination, the man just said, “Let’s run away from this cursed village. Screw everyone, the happiness that we are looking for is not here,” and the woman would reply, “What about my sick mom? How can I leave her behind?” Thus, life forces the woman to make a choice.

Who knows, maybe I was exposed to too much melodrama in the past. What do you see when you observe Rallis’ works, dear reader? Let me know.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!