Who’s the Jester on Lady Gaga’s Harlequin Cover?

Lady Gaga released an exclusive vinyl of her new album Harlequin, and fans quickly pointed out many easter eggs the artist had left on the cover. The...

Sandra Juszczyk 22 November 2024

Wassily Kandinsky painted some of the most beautiful pieces of art in a style that is instantly recognizable. The flurry of lines, colors, and shapes, demonstrates an ability to enchant art lovers without representing any recognizable forms; a hallmark of his oeuvre or creative output. Kandinsky felt that his style was ‘dissonant’, especially in terms of color, a musical term that relates to notes that clash when played together or next to each other. Whilst the featured example, his Composition VI, is chaotic, wild, striking, energetic, discontinuous, and so on – my opinion is that it is visually incredible and not at all dissonant, like ‘popping candy’ for your eyes!

The painting demonstrates so much of Kandinsky’s positive window into pre-war Modernism or Expressionism. Were it not for the effects of the two world wars on the mindset of Western European artists, Modernism would be quite different, owing its existence to the disillusion and devastation that had soured the atmosphere during this time.

Kandinsky’s early paintings are equally but entirely different in their beauty. Odessa, Port (1898) is an example from his early paintings that shows his connection with Impressionism; one would not be surprised if we were told that it belonged to Monet, but the color composition of the water in the bottom right hints where his technique would end up. His focus on the effects of the light reflecting off the water, and the way he renders the image of the boats, would also not look out of place amongst a collection of Turner paintings.

The key ingredient to their methods is the use of color; in each case, the colors are not unrealistic, they are often in fact the most realistic representation of a scene at a fixed point during the day. A lesser artist will often paint a more prescribed image than the one in each of these pieces. What each artist wanted was to bring originality to their color compositions in a way that is realistic, beautiful, and reflects the vividness of color encountered when the scientific properties of light meet the imagination of truly great artists.

In 1911, Kandinsky felt compelled to write a letter to Arnold Schoenberg, the essence being that he felt a connection with the artistic aims of the Austrian composer. In particular, Kandinsky liked the idea that his music was attempting to communicate an entirely new language – one that spoke from the soul and embraced dissonance:

In your works, you have realized what I, albeit in uncertain form, have so greatly longed for in music. The independent life of the individual voices in your compositions, is exactly what I’m trying to find in my paintings.

Wassily Kandinsky in a letter to Arnold Schoenber in: Arnold Schoenberg and Wassily Kandinsky: Letters, Pictures and Documents, Ed. by Jelena Hahl-Koch, Faber and Faber, London and Boston 1984, p. 57–58.

Schoenberg’s music can be incredibly difficult to listen to as it contradicts many of our musical expectations. It is not necessarily loud or abrasive, nor does it contain foul words or imagery; instead it consists of dissonant notes that sit awkwardly with each other, much like playing adjacent black and white notes on the piano, changing our anticipations each time a new note arrives. It is the musical equivalent of speaking a new language that makes no sense because we have never used these combinations of words before.

Kandinsky encountered Schoenberg’s music at a concert in 1911. The piece is Klavierstück op. 33a, an atonal piece of piano music that prompted Kandinsky to go home and paint his Impression III (1911). Both the artist and the musician wanted to communicate through a new language, one that expressed their ideas through unrecognizable elements.

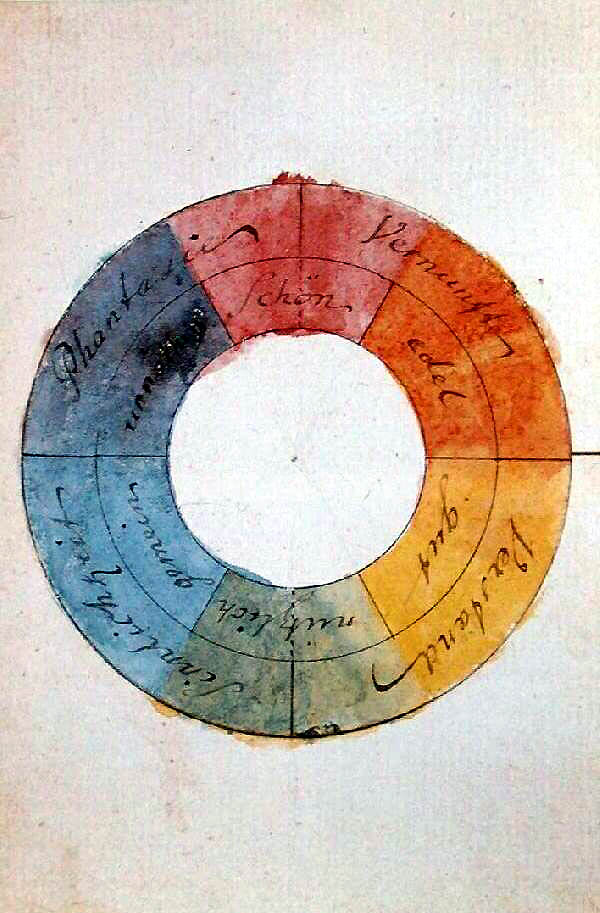

The latter part of the 19th century had been about using colors that were in harmony with each other, based on the theories of Goethe, Chevreul, and Hayter, finding application in the paintings of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Kandinsky used dissonance in his color relations, intending to turn these color theories on their head. He intended to create ‘compositions’, as he called them – paintings to us, which clashed colors together in a form of visual dissonance. Artists of the Post-Impressionist movement, such as Seurat, pioneered the ‘chromo-luminism’ method (Pointillism), where each spot of color had a complimentary color from the opposite side of the color wheel next to it, to create a brighter more vibrant image. It was Kandinsky’s idea to contradict this method to his own ends.

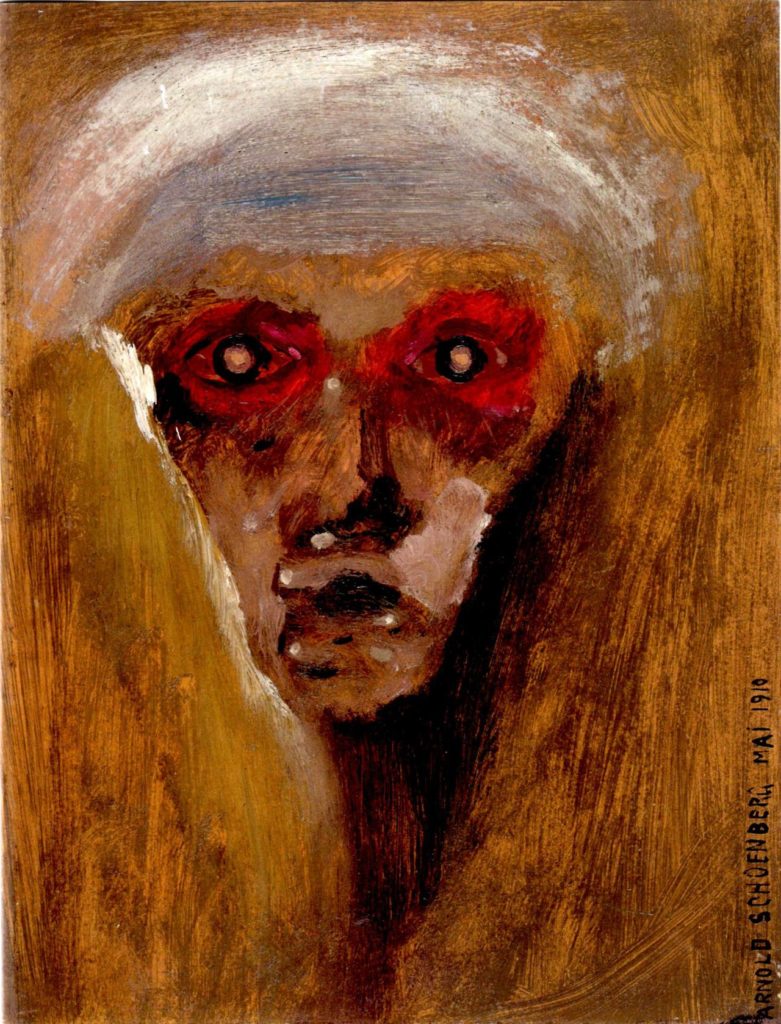

This quote below is an excerpt from Kandinsky’s first letter to Schoenberg, which led to many more, as each shared their thoughts on a new musical and artistic language. Schoenberg thought of himself as an artist also, painting pictures such as The Red Gaze (1910) and many more self-portraits and other types of imagery, where his musical desire to express dissonance also appeared in his paintings. This is a well-tread discussion amongst musical academics, as the dis-functionality in the painting is often married to the difficulty in listening to his music. What the letters between Kandinsky and Schoenberg reveal is a desire for order, system, and form. Kandinsky writes:

Construction is what has been so woefully lacking in the paintings of recent times, and it is good that it is now being sought. But I think differently about the type of construction.

Wassily Kandinsky in a letter to Arnold Schoenber in: Arnold Schoenberg and Wassily Kandinsky: Letters, Pictures and Documents, Ed. by Jelena Hahl-Koch, Faber and Faber, London and Boston 1984, p. 57-58.

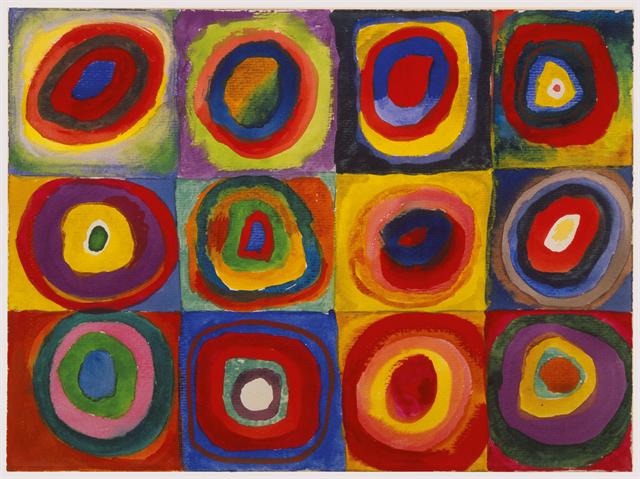

It is easy to keep returning to the simplicity of a painting like Squares with Concentric Circles (1913) as a ‘go to’ visualization of Kandinsky’s methods, ideals, and an embodiment of ‘Abstract Art’. The painting contains many of his key traits, such as geometric shapes and vivid colors, as well as simplicity that either focuses the message or confuses those who see art as only a means of capturing an image.

Like Schoenberg, Kandinsky wanted to speak through original means, using a new kind of order. This is much like having a fresh new idea but not wanting it to come out sounding like the same old thing – much like politics! This opposes any idea that Schoenberg created music that was chaotic or random; on the contrary, he just did not want his music to sound the same as his predecessors’.

Both the artist and the composer wanted to create beauty in their art forms, but not featuring the same typical forms as those in Kandinsky’s early works: a boat, a river, the sky. Indeed, almost none of his paintings contained human forms except for odd ones like the mysterious Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter, 1903).

By discarding conventional forms such as boats and trees, Kandinsky was able to find beautiful expression through geometry, color, and musically inspired counterpoint. Whereas Schoenberg’s music is often thought of as difficult to palate, the uniqueness of Russian artist Kandinsky’s colors and lines are illuminating, bright, and appealing to the eye.

While so much of the discussion around Kandinsky focuses on the Der Blaue Reiter Group, the Bauhaus, his former life as a law graduate, and often just Concentric Circles, this discussion shows his evolution from copy-cat Impressionist to a defining Modernist of an era, creating a new artistic means of expression that is bold and beautiful, bringing a new definition to the term ‘dissonance’.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!