5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

The eyes of an artist put to the service of art can reveal to us an unspeakable world that is very present around us. But what does this world, this inner universe look like when the artist’s vision deteriorates? When it becomes troubling, meets illness, and when abstraction blends with impression? What remains of a painter when the tool is removed from its owner’s hand? What happens when the painter is deprived of his essence? Read the story of Claude Monet’s blindness.

Despite the many trips he made to see different landscapes, it was Giverny where Claude Monet settled with his large family in 1883. An hour from Paris, he lived there until the end of his life. At that time, his creativity met very few obstacles and his work received much awaited recognition. Monet decided to create his ideal world in his grandiose garden, which was a source of infinite inspiration that has reached our times through his series of paintings of water lilies, Japanese bridges, and flowery pathways.

His house was a sanctuary of unfailing beauties dedicated to color, nature, and quite simply to the joy of life. A place that was marked by the footprints of its many inhabitants. Today, the house of Giverny welcomes more than half a million curious minds from all around the globe every year, where they let their senses be challenged in the best ways possible.

It was at the beginning of the 20th century, that the artist’s path took an unexpected turn. Claude Monet began to complain early in 1908 about discomfort in his right eye and gradually weakening vision in both eyes. After a medical consultation in July 1912, the findings were Monet had contracted cataracts.

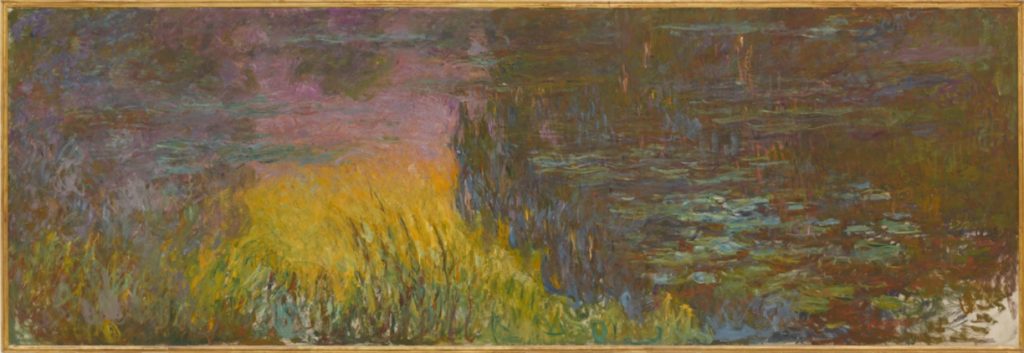

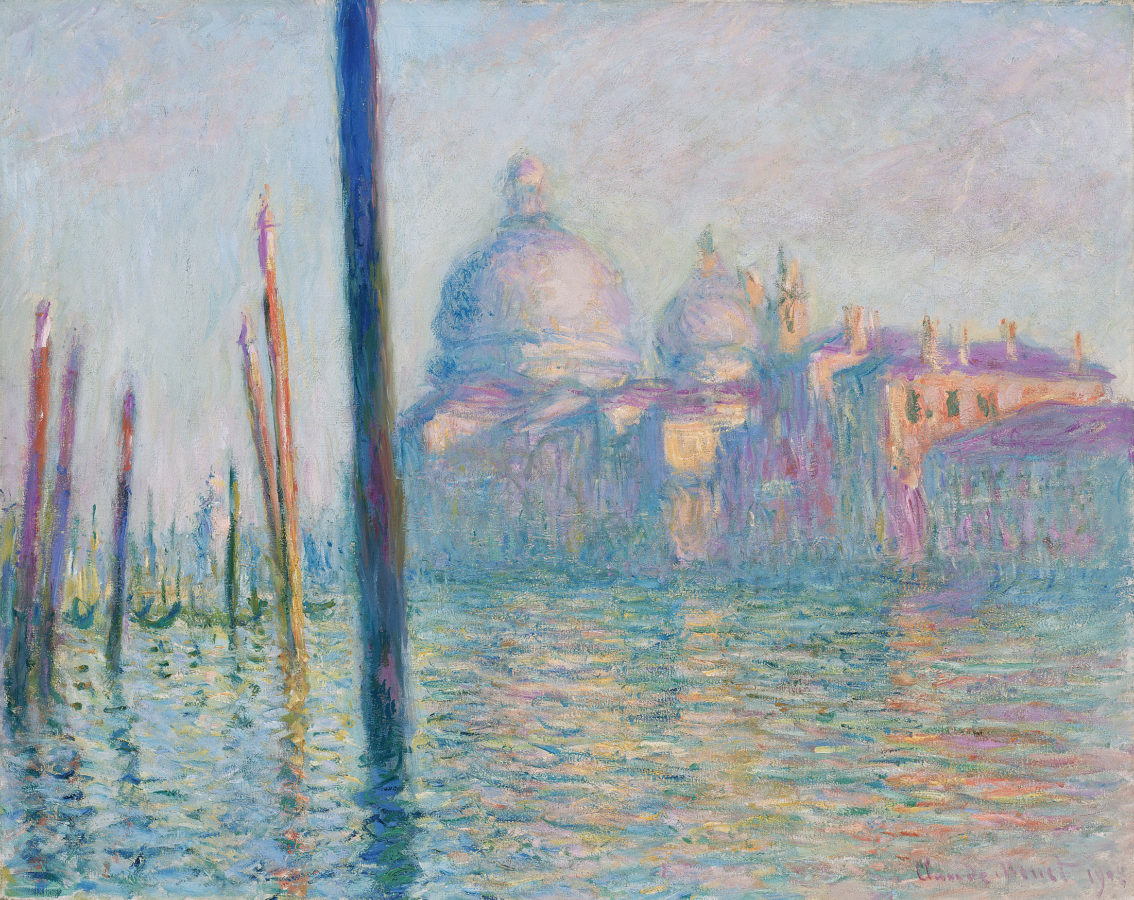

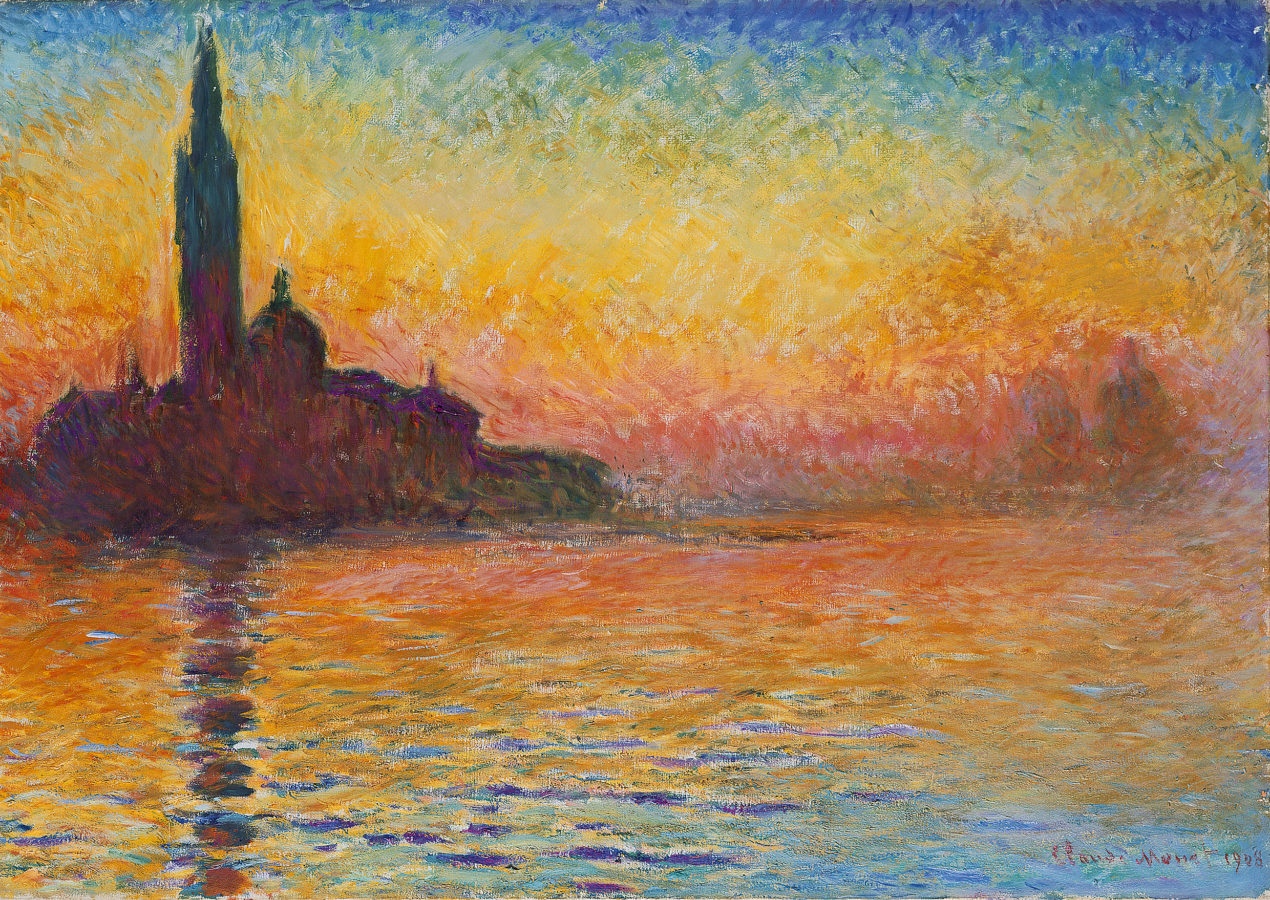

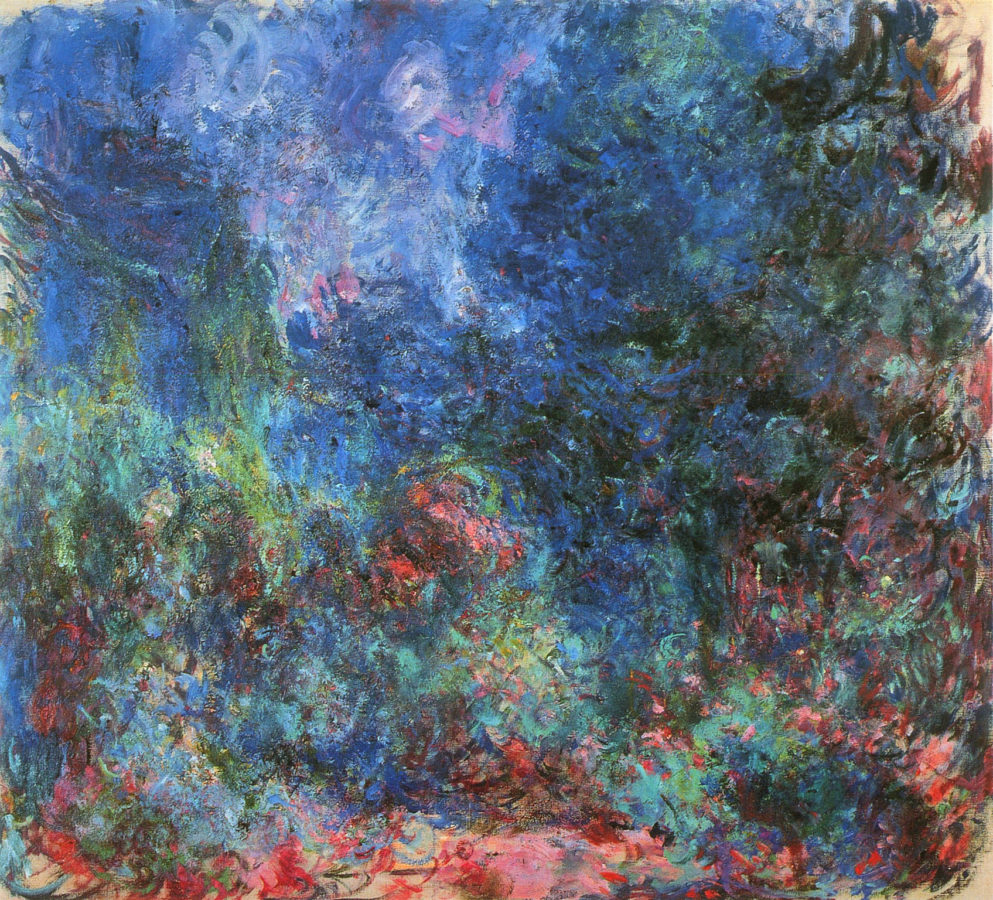

A cataract is a progressive opacity of the eye lens that filters colors. As the cataract progresses, whites become yellowish, greens become yellow-green and reds become orange. Blue and violet give way to red and yellow. Meanwhile, details fade, and contours become blurred. The first signs of the disease can be seen in the work that Monet carried out in Venice in 1908.

Despite the alteration of his vision Monet continued to work, and by observing the evolution of his work, we also witness the progress of his disease.

Monet did not want to discuss having any surgery because he always remembered Honoré Daumier‘s blindness after such a surgery. Indeed, at that time cataract surgeries were only in their early development; anesthesia was only superficial through the use of cocaine.

Thus, he used eye drops and glasses during the following 14 years which helped him work without slowing down for a moment. On November 12, 1918, the day after the Armistice, Monet wrote to Georges Clemenceau:

I am about to finish two decorative panels, which I want to sign on Victory Day, and come and ask you to offer them to the State, through your intermediary.

The intention of the painter is to offer the Nation a true monument to peace. After Paul Léon’s (Director of Fine Arts) acceptance, Clemenceau managed to persuade Monet that instead of two panels he would produce an entire decorative ensemble of 19 paintings. But it wouldn’t be that easy, and in September 1922 Claude Monet had to face the inevitable truth: the miracle drops and various glasses had only postponed the inevitable surgery. The painter was almost blind…

In the letters that Monet exchanged with Dr. Charles Coutela, from 1922 to 1926 we can follow this stage of his life:

My dear Doctor,

Giverny, October 20, 1922.

I believe that the time is approaching when I should surrender myself to you with confidence, but not without concern, I confess. The first operation could be done in the first week of November in Giverny, as you promised, and fifteen days later in Paris, for the second. I’m fine, thanks to your drops that make my vision better, not to say good. But I do not have anymore and I lost your prescription and the supplier’s address. I would, therefore, be very grateful if you would send me a second bulb by post, and as soon as possible, because I would be sorry to miss one, even for one day.

Thank you in advance and believe in my distinguished feelings.

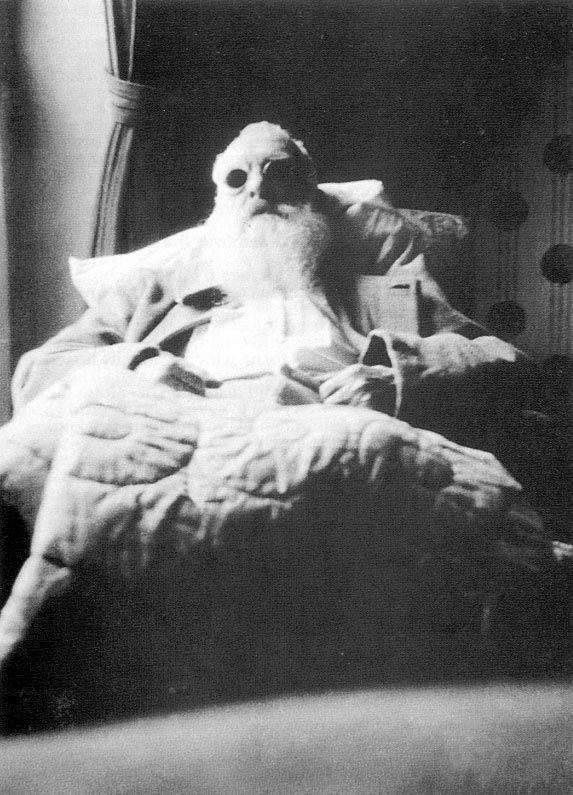

With the unfailing support of Clemenceau and his family, Monet finally underwent the first operation in January 1923. The protocol is extra-capsular extraction with mass washing. This operation would partially restore his sight, and the same evening the anterior chamber of his eye was reformed. Despite this Monet suffered a lot, he was disappointed and disturbed by the optical correction which pushed him to refuse any surgery on his left eye.

He also suffered because of the criticism of his works, which were considered unfinished as the white of the canvases remained visible. The progressive disappearance of figuration for the sake of studies of light did not help. Yet, here we are, entering the abstract period…

While observing the paintings of this long and painful period of Monet’s life, I find myself posed with a dilemma: how to put into words a painting entering the field of abstraction? I see only one solution: I will for a moment forget the technical terms and keep the only tool suitable to me at the moment, my own subjectivity.

In contrast to Narcissus, Monet is not in love with his own reflection, what he sees in the water in front of him is the purity of light, its undulations, and transformations. Forget the trees and water lilies for a moment and rest your eyes on the water…

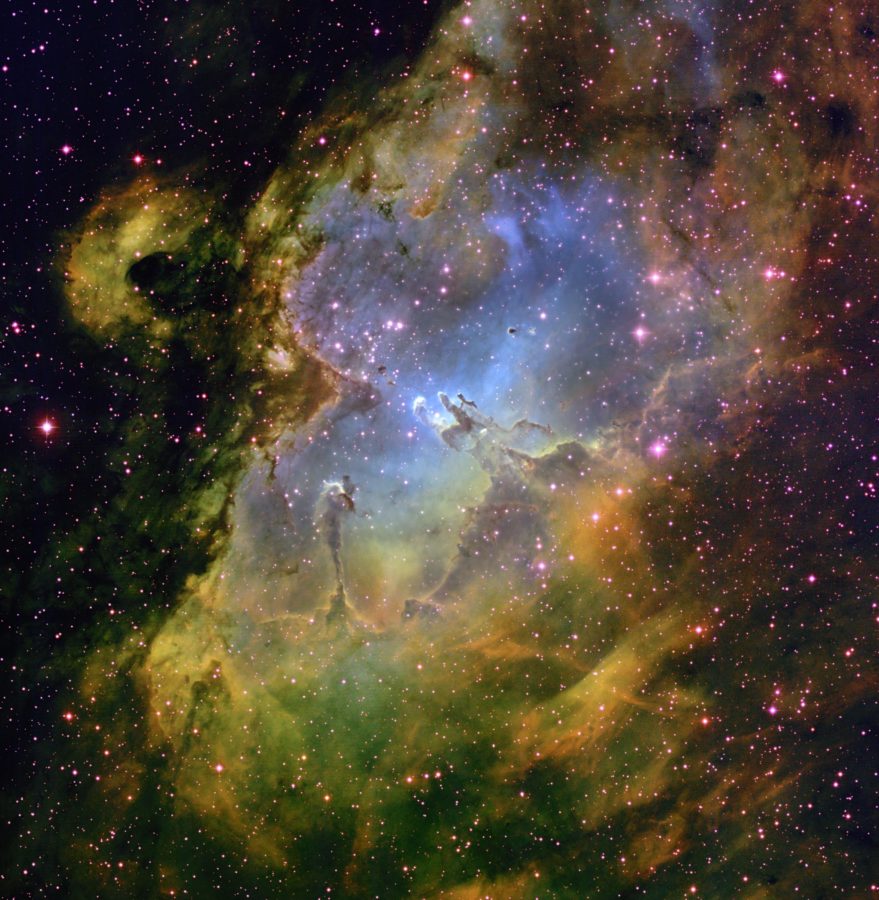

Have you ever seen the pictures of nebulae, those piles of gas and interstellar dust present in our universe? Particles that are in free and constant movement which suggests a ballet of sublime chaos, a perfect harmony… I am no longer in front of a known landscape but at the beginning of a journey into another, almost immaterial, world. A world framed by the edge of a pond and the caress of the branches, of a weeping willow on the water’s surface.

Earlier in his life, Monet was already telling his students:

When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have in front of you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Just think of this: here is a small square of blue, pink, an oval of green, a stripe of yellow, and paint them exactly as they appear to you, exact colors and shapes until they give you your naïve impression of the scene in front of you.

This is the level of honesty and intensity that his paintings offer us: a moment of paused life, which sometimes seems represented in haste as if he felt an urgency to get to the essence of things as soon as possible. He took advantage of each moment when his vision became somewhat incorrect, he took to his brushes, forgetting the physical and mental pain of the disease and the surgeries.

In an excerpt from a letter dated April 9th, 1923, Monet wrote to his doctor:

Giverny, April 9, 23.

I went through bad days of nerve pain or other, fortunately, calmed and passed by pills. Apart from that, I see less and less, with or without dark glasses. The excessive light that we have tires me so much that I am obliged to confine myself in the darkness of the room. Today, I have had strong spins in the center of the eye itself, and, moreover, I always have the sensation of having water in my eye.

Receive, dear Doctor, my best feelings.

Claude Monet

And there we are at the beginning of 1926, a year that begins on a positive note for the 86-year-old artist.

Dear Doctor and Friend,

Giverny, January 4, 26.

I thank you for your good wishes, very touched that you do not forget me; me either, even though you made me suffer, which is nothing since I have regained my sight and that is not forgotten. I hope that on sunny days, you will give me great pleasure to come to Giverny for lunch. My regards and best wishes.

Claude Monet

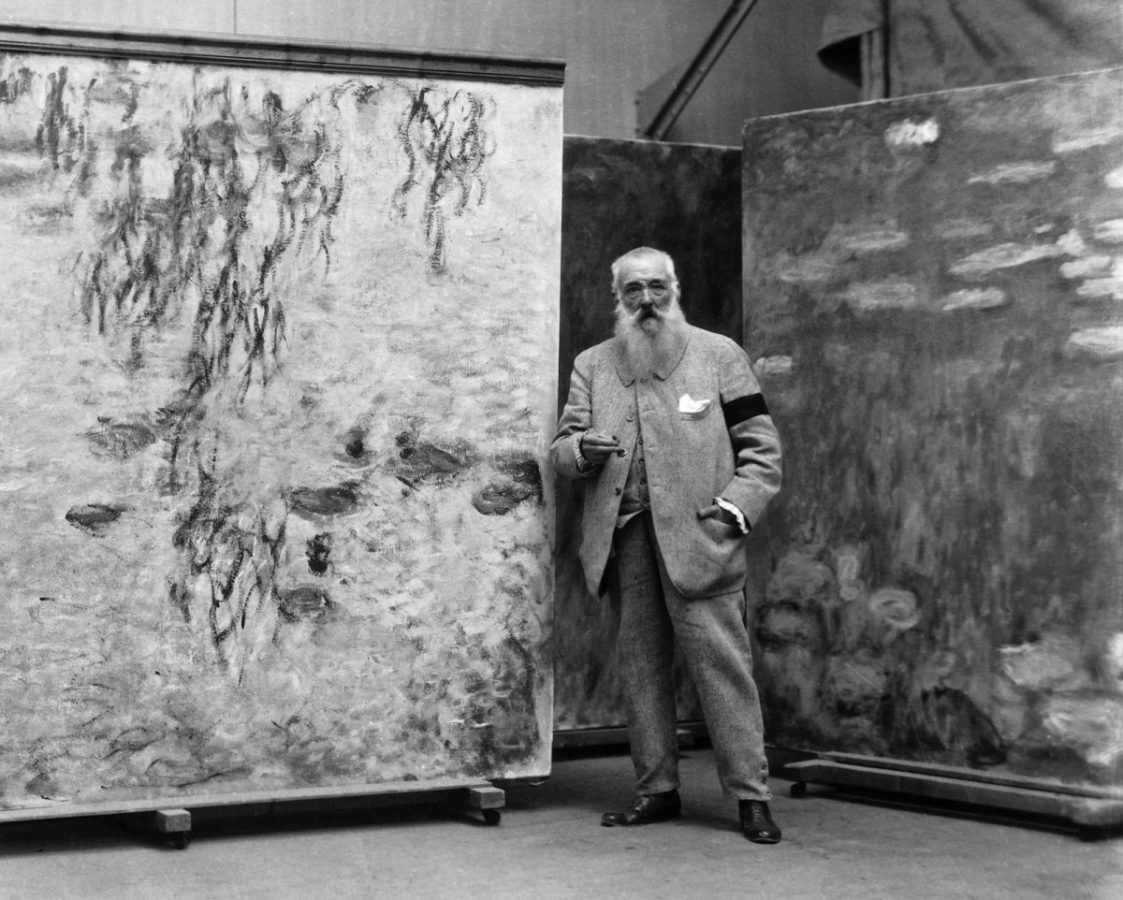

Despite many hesitations and requests for additional time to deliver the 18 paintings for panels of the Nympheas, today at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, Claude Monet was making progress. However the disease was progressing too, and his obsession to paint the real was reinforced by an uncontrollable fear of permanently losing his sight. He felt he must finish his monumental masterpiece begun 12 years before.

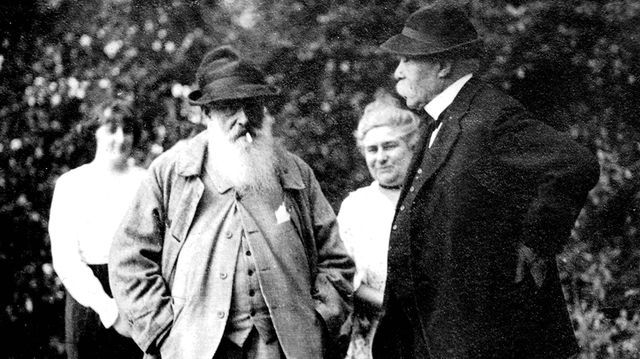

When reading Monet’s letters to Clemenceau, one can feel his despair. Here is an excerpt from the letter that Clemenceau wrote him to urge his dear friend to finish this work:

My unfortunate friend,

No matter how old, no matter how damaged, a man, artist or not, has no right to break his word of honor – especially when it is to France that this word was given.

I was going to write to ask you to go to lunch with you on Sunday. I absolutely renounce it, and if you maintain your mad decision, I will also take one that will be more painful perhaps to me than to yourself. […]

You are old and diminished in your vision. But your genius stayed with you. You want to make it bad for you. My consent to this cruel whim will be denied. But a real miracle has happened. You could paint and you painted bigger and more beautiful than ever. The rest I don’t have to remind it to you. Your conscience, deliberately bruised with your own hands, will remind you of this until your last breath. I tell you the truth naked, having nothing more to spare with you. […]

These two men with strong characters were always there for each other but friendship turned out not to be enough. Weakened by incessant work, Monet contracted a pulmonary infection which confined him to bed. Clemenceau was called to his friend’s bedside and Monet died in his arms on December 5, 1926.

When Georges Clemenceau saw Monet’s coffin covered with a funeral sheet, he claimed: No! No black for Monet! Black is not a color! He tore off a curtain of cretonne in the colors of periwinkle and hydrangea and put it in on the coffin instead.

The 19 panels of this “Sistine of Impressionism” (André Masson, 1952) were given by his son, Michel, to the directory board of the Beaux-Arts. Camille Lefèvre finished the installation of the two elliptical rooms under the supervision of Clemenceau and the exhibition opened its doors on May 27th, 1927 under the name Claude Monet Museum.

What I had been observing for almost 2 hours sitting in an oval room at the Musée de l’Orangerie, surrounded by the sublime decorative ensemble of water lilies, was the vision of another world, another layer of the universe that we don’t get the chance to see. A world that cannot be described with words.

Surrounded by the “illusion of a whole without end, of a wave without horizon and without the shore,” a vision provoking the awakening of the senses and the sleep of the body, a journey into space where abstraction is the new norm. If emotion can equally replace speech, then perhaps abstraction can meet Claude Monet’s world, and open for us a new horizon.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!