5 Expressionist Artists You Should Know

The purpose of art for a group of avant-garde individuals at the turn of the 20th century was no longer the realistic rendition of the natural world,...

Guest Profile 29 February 2024

Austrian artist Egon Schiele is best known for his shamelessly erotic and frank representations of human form. But alongside his startlingly revealing portraits and raw nude studies lie haunting journeys into fragile existence through town paintings and landscapes. His expressive, vulnerable bodies inform a notorious core of work, but Schiele was also a prolific chronicler of the natural and urban environment.

In 1910, Schiele decided to flee the urban bustle of Vienna for a yearnful sojourn in the rural town of Krumau, the birthplace of his mother. The town is now modern-day Český Krumlov in the Czech Republic, but in the early 20th century, it was still part of the sprawling Austro-Hungarian empire. Accompanied by artistic companions Anton Peschka and Ervin Osen, Krumau provoked a creative spark in Schiele, inspiring a vast amount of artistic output for the rest of his short life. But rather than providing a peaceful backdrop of pastoral existence, Krumau enhanced Schiele’s preoccupation with isolation and unease. Despite escaping the decadent alienation of Vienna, Schiele compounded his fundamental themes of naked exposure and mortal scrutiny into fragmented urban townscapes.

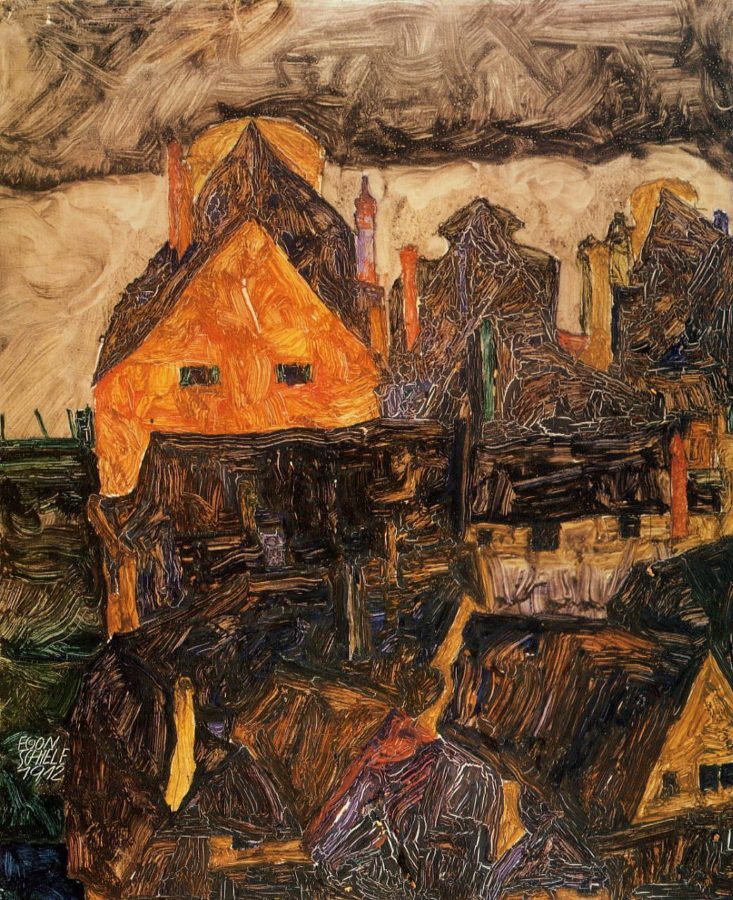

His quest to explore the spiritual essence of his environment is Expressionist in notion, revealing the hidden core of human experience through visual exaggeration and subjective insight. The claustrophobic nature of his unsteady throng of houses on the Moldau river (above) emphasizes the compressed nature of this decaying urban vista. Solid vertical lines support the waterside settlements, yet are helplessly undermined by the sinuous curves of their own crumpled roofs. Like his portraits, bravely disclosing the twisted turmoil within, human anguish would leave a similar trail of tension in the everyday. This remote town would serve as a visual conduit for his own melancholy reflections.

Despite his longing for a provincial idyll, Schiele and his friends were to encounter a degree of hostility from some of the more conservative residents of Krumau. However, this didn’t prevent him from planning a permanent move there in 1911 alongside his partner and muse, Wally Neuzil. For a time they enjoyed a peaceful existence in their little cottage by the river, but his paintings remained haunted by the town’s ancient winding streets and compact medieval design. Vienna had often instilled a feeling of repulsion in him.

Crumbling artifice and decaying splendor were slowly allowing a new generation of Modernist thinkers to impose a fresh set of values on a decrepit way of life. The motif of the dead city was a theme he returned to on numerous occasions during this period. Sketches of a clustered group of houses served as a reference for a series of particularly inanimate, morbid scenes. This is an eternally nocturnal townscape devoid of inhabitants. In fact, most of Schiele’s urban landscapes are empty of people. Instead, he conjures expression and meaning from buildings and the physical features that connect them. Natural elements such as mountains, sky, and rivers only serve to enhance the oppressive atmosphere.

The influence of his mentor, Gustav Klimt, shadows much of Schiele’s work, and he held him in high regard for much of his life. Decorative elements and patterning devices are commonplace in both artists’ work, each achieving a graphic, two-dimensional quality to their illustrative output. But Schiele superseded Klimt’s ornamental trimmings in many ways as his own work matured. Schiele’s perspective may be darker and more nihilistic, but his fractured patterning is grounded in a desperate search for humanity in an ever-widening void.

Indeed, as the years progress, Schiele’s townscapes, whilst still devoid of human figures, become evermore considerate of their absence. His view of the Krems an der Donau neighborhood of Stein is a conflictingly lively portrait of an empty settlement. Windows are actively blinking and alert whilst the adorning embrace of the mountains provides a soft counterpoint to the stagnant, grey flow of the Danube.

Much of Schiele’s townscapes after 1912 were based on sketches, in particular, those scenes of Krumau that frequently appeared as large-scale paintings. His stay there had been cut short by a town incensed by his curious appearance and unorthodox behavior. Relocating to the Lower Austrian town of Neulengbach didn’t resolve his disputes with a society at odds with libertine attitudes and he eventually served time in prison due to local outrage over young children visiting his studio where erotic drawings were displayed.

Paintings of Krumau continued to be obsessively produced even when Schiele settled back in Vienna after his brief internment. He returned for brief spells, staying at local inns to hastily recapture the lonesome insight he so accurately conveyed across much of his art. Two widely different works from the intervening years of 1914 and 1915 resume his investigations into de-populated space with flourishing signs of mortal activity.

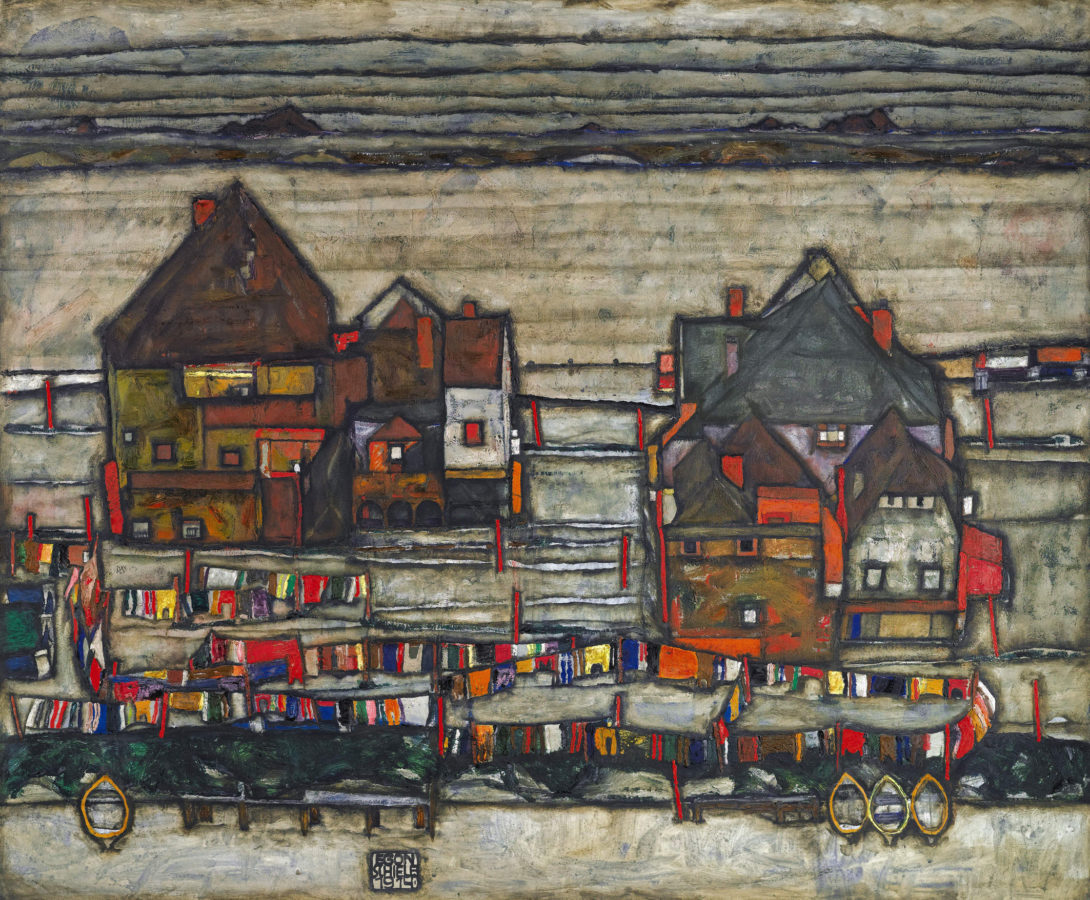

The horizontal harmony that unifies the earlier painting (above) combines solid rows of human occupation with twinkling windows and sinewy lines of multi-colored washing. These beacons of individuality counter the bleakness of the mountains and river. Occupation is isolated within a frame of blank existence, but human lives thrive amidst the emptiness. The little boats scattered along the water’s edge are timely reminders of personal and collective resilience in the face of adversity.

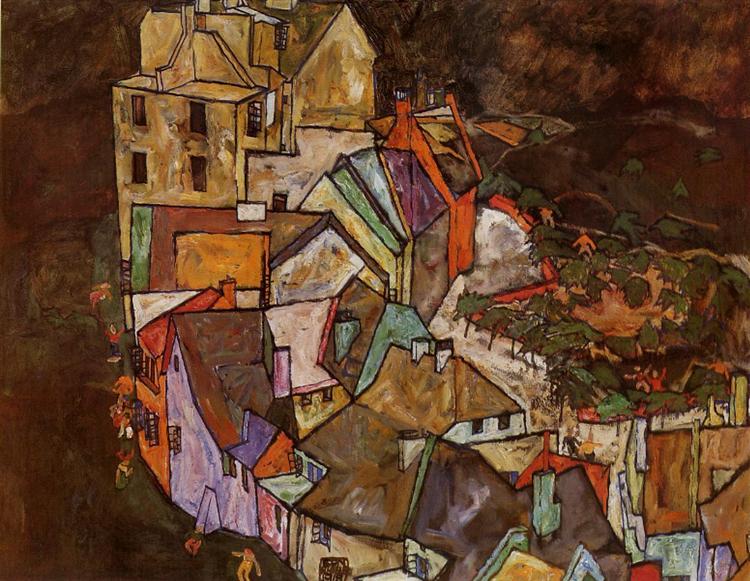

The crescent painting of 1915 (below) is more sumptuous in comparison. Neat horizontals have been replaced by a luscious curve that appears to forcefully drag the composition to the left of the piece. Schiele is commonly applauded for his draughtsmanship. The dynamic use of line and reclining nature of this view recall the twisting contortions of his erotically charged nudes. Washing lines are similarly vigorous in their active display. This is a potent tapestry. A town once again devoid of people, yet somehow alive despite their truancy.

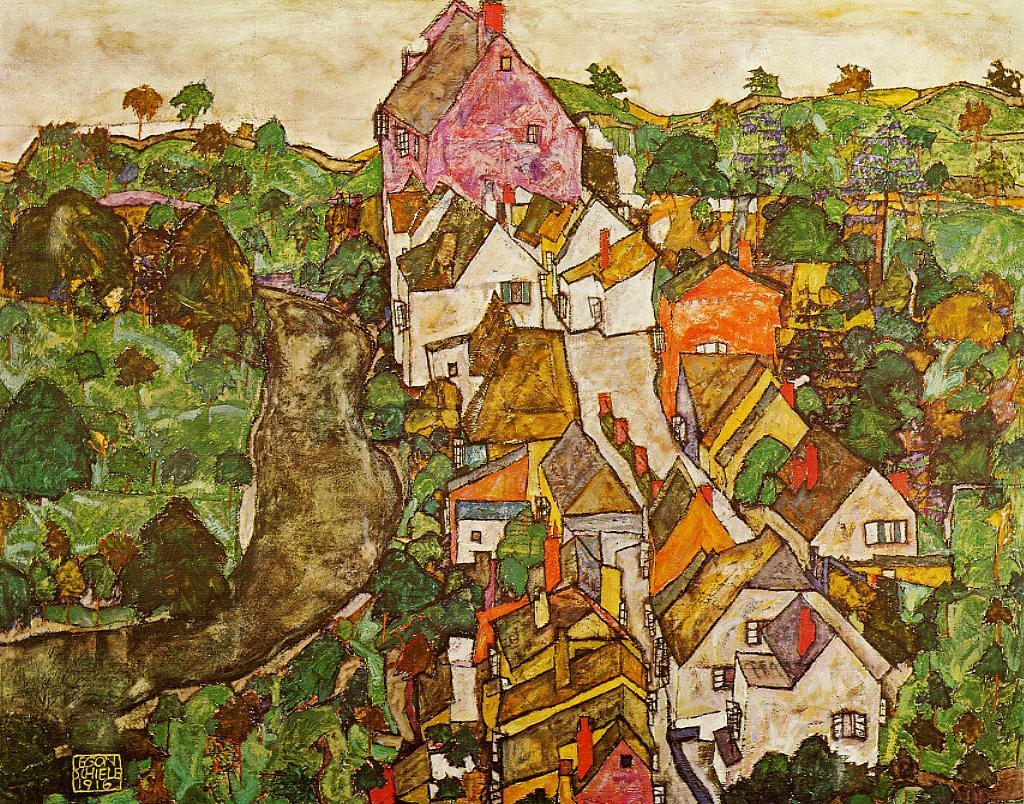

By 1915, Schiele had spurned his partnership with Wally Neuzil to marry the more socially mobile Edith Harms. Though echoes of Neuzil resonate throughout his later work, married life instilled a calmness in Schiele’s approach. Still powered by underlying strife, the discord becomes restrained and controlled. The color also appears more vibrant. The pinks and greens in this late Krumau landscape of 1916 hint at the radiance of the sun and domestic serenity, as opposed to the gloomy torment of his previous foreboding dead zone.

Following the death of Gustav Klimt in 1918, a victim of the Spanish Flu pandemic sweeping the globe during that year, Schiele was posed to become the leading artistic figure in Vienna. The disciple was finally due to inherit the mantle of his master. But the deadly influenza also tragically struck Edith, who was six months pregnant. Schiele died from the disease three days later. He was 28 years old.

At the juncture of his untimely death, post-war negotiations towards the eventual Austrian Republic were claiming the last vestiges of disintegrating Habsburg rule. Schiele had high hopes for a new society where a brotherhood of artists would assist in building a better world for mankind. It is fitting to interpret one of his final townscapes as a wishful longing for this utopian awakening. Although the painting is enveloped in somber darkness, we see actual people emerging, blinking and confused, from a sweeping arc of multi-colored abodes. We can fancifully construe this as a convenient metaphor for the forthcoming dawn, the end of a crumbling empire and the birth of a brand new day.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!