The lives of artists are a constant source of fascination and the life of Staffordshire born artist of John Currie must rank amongst the highest. Born in 1884 in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Currie’s early promise as a painter was cut short by a life marked by the tragedy of loving too hard and too strong.

Currie was educated at Newcastle-under-Lyme and Hanley Schools of Art and at the Royal College of Art. He began his working life as a ceramic artist before moving into teaching in Bristol. Following a stint in Dublin as an art Inspector, Currie made the step to London in 1910.

A member of the Slade Art Group, Currie was part of the a group of artists who called themselves the ‘Coster Gang’ led by CRW Nevinson, and which included Mark Gertler; both men becoming close friends of Currie. Nevinson described the group as “the terrors of Soho” and the wildness of the group was reflected in their attitude to their art. A lot of works by Currie can be now seen in The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Hanley.

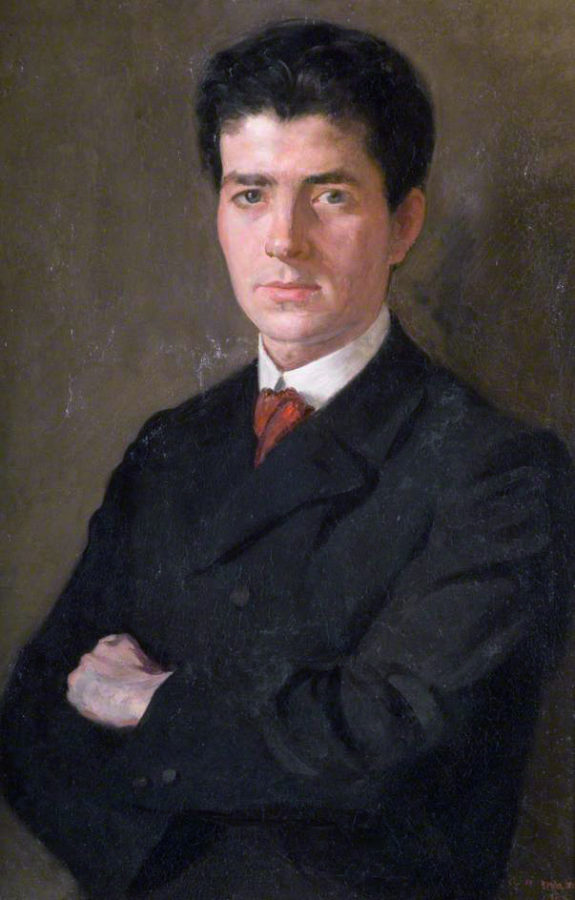

Mark Gertler quickly became a particularly close friend. This portrait of Gertler was painted by Currie in 1913:

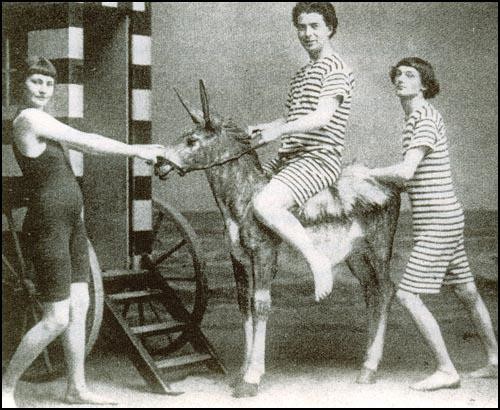

Where Gertler was ‘pretty’, Currie was the more rugged looking of the pair. In this portrait, Currie captures the waif-like appearance of Gertler as seen front and centre in this photograph of the Slade Group picnic of 1912:

The friendship centred around the fact that Currie was no threat to Gertler’s relationship with fellow artist, Dora Carrington as Currie was already married with a young child. This did not stop Currie, however, from embarking on a love affair that would end in the ultimate tragedy.

Neo Primitive

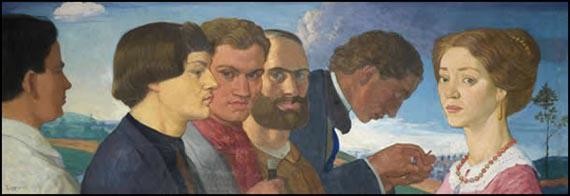

By 1911, the ‘Coster Gang’ were now calling themselves ‘Neo Primitives’ due to their fascination with the Renaissance style. Currie’s 1913 painting, ‘Some Later Primitives and Madame Tisceron’ is an excellent example of the influence:

Utilising a Italian backdrop and with the use of tempera, Currie portrayed Gertler, Nevinson, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and the proprietor of their favourite cafe, the Petit Savoyard Café in Soho in a style that reflected this passion for the Renaissance style.

Other paintings by Currie from this period, began to demonstrate the primitive style that was being championed by Picasso in Paris: elongated figures mask-like expressions and the use of a restricted palette.

This painting, ‘The House’ is reminiscent of the cubist style, geometric shapes rising Tina peak in the centre of the canvas creating a beautiful symmetry that draws the eye along the rooftops.

“Flower-like loveliness”

Despite being married, Currie had met and fallen in love with the 17 year old Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Henry. Dolly was a clothing model in a department store and, although it is not noted how they met, once they did, the tempestuous nature of their relationship quickly escalated. When Currie’s wife discovered the affair, Currie left her and moved in with his siren.

The first painting of Dolly, entitled ‘Head of a Girl’ is quite lovely.

The vibrant red of her hair and plump lips give the painting a sensuous quality; she looks out of the canvas with a slight sideways gaze: she is not a demure maiden, but a woman aware of her own sexuality. The tiny jewel in her hair band gives her an exotic quality and her smile is a knowing one. The artist was clearly in love.

The art collector and friend, Michael Sadlier wrote of Dolly that she was “of flower-like loveliness, but lascivious and possessive to the last degree.” The pair moved in together in August 1911, but the relationship was rocky to say the least. Dolly would frequently goad Currie to the brink and then retreat in order to win him back, resulting in violent rows.

“…one must love chaos to give birth to a dancing star.”

In early 1914, the relationship was once again at an end. Friends such as Edward Marsh were starting to to be concerned. Currie had threatened violence in the past and his threats of suicide were rising. Mark Gertler was also becoming concerned and began to talk about ending his friendship with Currie, telling Dora Carrington, “The atmosphere he lives in stifles me”.

At a lecture in Leeds University, Currie’s anguish over the end of the affair spilt over. Professor Michael Sadler and Currie spoke late into the night and Currie revealed that he could hardly keep from suicide.

This portrait of Dolly is in stark contrast to the one he painted a year earlier:

Entitled, ‘The Witch’, Dolly is far more open in her gaze; her lips have a slight sneer playing on them and she holds her hair loosely in her hand as if it is about to fall, teasing the man she is intently viewing.

The pair were reconciled once again in March, 1914 and Currie decided that living in Brittany might be the answer. All was well at first, but Dolly, always a city girl, became bored and returned once more to England. Currie moved on to Paris and then Cannes, continuing to paint.

But, as was becoming the norm, Dolly again changed her mind, writing to Currie that she did love him and he returned to join her in Cornwall. Currie had a pure moment of joy and clarity, writing to Marsh, “I’ve had a long spell of chaos. I think it is Nietzsche, isn’t it, who says something about one must love chaos to give birth to a dancing star.”

This idyll was not to last and chaos soon returned. After yet another quarrel in which Currie threatened to throw her off a cliff, Dolly escaped to London.

Tragedy in Chelsea

Inevitably, the parting could not be a simple one and the tragedy that was about to unfold was almost inevitable. Fuelled by rumours that Dolly had posed for pornagraphic photographs and was spreading rumours about him, Currie was losing his reason. He wrote to a friend, saying, “A very fury of remorse and love and sorrow is raging in me… I am looking for a place I can bury my heart and forget.”

But, Currie could not forget. On 8th October, 1914, Currie made his way to Dolly’s rooms in Chelsea. A series of shots rang out. On investigation, Dolly was found lying dead and Currie was barely alive. Asked why he had done it, he said, “I loved the girl.”

Taken to hospital, Currie lingered for some hours, seemingly unaware of what he had done. Mark Gertler rushed to his hospital bed, quickly followed by Edward Marsh to be with their friend. His dying words were quite simply: “It was all so ugly.”