Blood in (and as) Art

One of the first known expressions of human creativity, the Lascaux cave paintings, were created with blood, a material that has remained significant...

Kaena Daeppen 10 June 2024

Why did Michelangelo portray Moses with horns? Why are there monkeys in Giulio Romano’s Chamber of Giants? And why does the Nativity scene represent Jesus with an ox and a donkey? Well, these amongst others are all mistakes caused by incorrect translations. Let’s start from the beginning and explore the five translation mistakes that changed art history.

Philology (from the ancient Greek word philologhía, composed of phìlos, “friend, lover”, and lògos, “word, speech”) is the discipline that studies texts of various natures and from different periods, in order to determine their original form and meaning.

However, when we consider the length of time that passed since sacred texts and myths (that originally came from the oral tradition) have finally been written down… it can be thousands of years. As time passes, some texts are lost, others destroyed or ruined, and many are mistranslated. Besides that, as a well-noted Latin expression states, errare humanum est, meaning that mistakes happen. Yet, some mistakes are more important than others: so, let’s find out which errors changed art history forever.

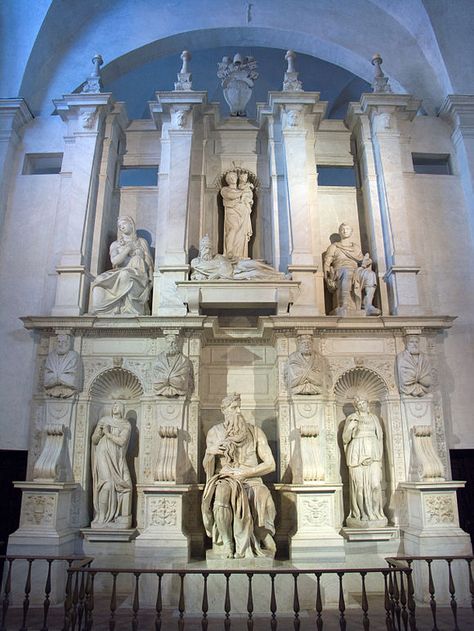

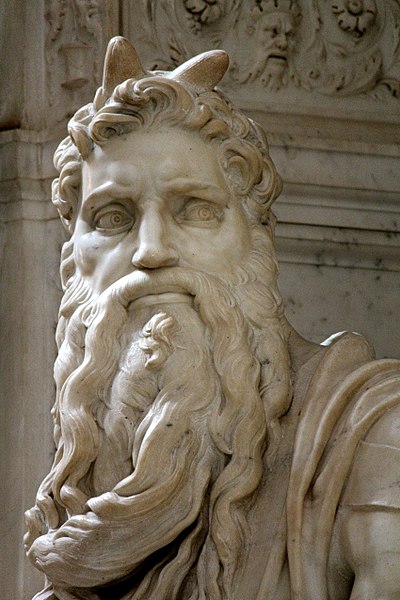

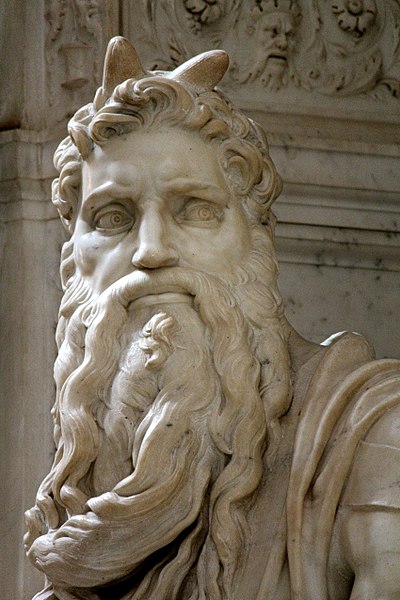

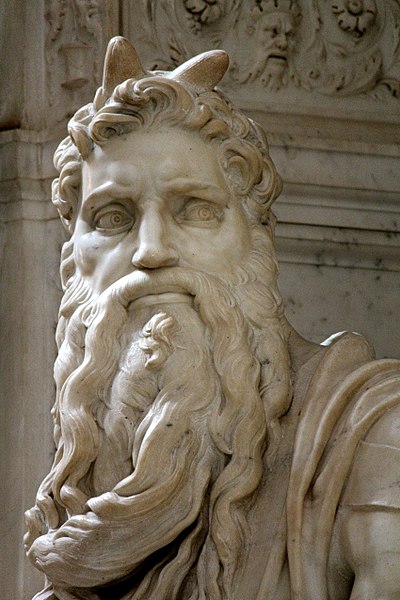

In 1505, Michelangelo had just gained great fame and success for his masterpiece David; that’s why Pope Julius II (the founder of the Vatican Museums) commissioned him to create his funeral monument, originally intended for St. Peter’s Basilica.

The first plan for the monument was very elaborate. Michelangelo designed a colossal three-level structure with many huge statues that would have contained the Pope’s tomb. However, when the Pope died in 1513, his heirs couldn’t afford such an expense, so they modified Michelangelo’s original design. They significantly reduced its size eliminating the mausoleum and most of the statues.

You may already recognize the figure of the main statue of the finished design; it represents Moses, one of the most important Biblical characters. As Giorgio Vasari described it:

The beautiful face, like that of a saint and mighty prince, seems as one regards it to need the veil to cover it, so splendid and shining does it appear, and so well has the artist presented in the marble the divinity with which God had endowed that holy countenance.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, 1550.

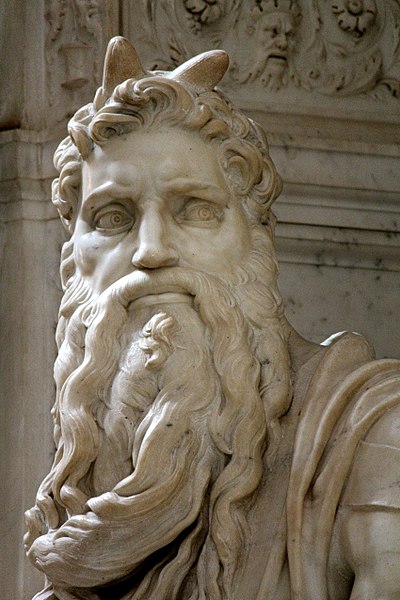

There were many people who tried to understand and explain Moses’ gaze and mindset (including Freud!), but above all many have wondered: why does Moses have horns?

Michelangelo just followed the iconographic convention common in Latin Christianity. The mistake stems from Saint Jerome’s mistranslation of a word in the biblical passage found in Exodus chapter 34. The Douay-Rheims Bible translates Jerome’s Vulgata as:

And when Moses came down from the Mount Sinai, he held the two tablets of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord.

Douay-Rheims Bible, Exodus, Chapter 34, verses 29-30,35

The Hebrew script transcribes the consonants only, while it transcribes vocals as small symbols near consonants. That is why it is believed that Jerome made a vocalization mistake: instead of translating the Hebrew term קָרַ֛ן, qāran, meaning “shining” or “emitting rays”, he translated it as qeren, meaning “horn”.

So, Moses was shining from having talked with God (and who wouldn’t? be). It turns out that he didn’t actually have horns!

There have always been epidemics and plagues that have overwhelmed the history of humankind. These calamities cause profound changes in history, society, and culture. The Black Death, also known as the Plague, or the Pestilence, was a pandemic disease that spread throughout Eurasia and North Africa, peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351. It is estimated to have killed up to 75-200 million people in total, reducing Europe’s population by between 30% and 60%.

The Plague has obviously had a great influence on art history. Lots of different artists have portrayed it on numerous occasions during the following centuries. As one of its common names is the Black Death, many artistic representations depict it as a black figure or as a creature wearing a black robe.

As we see in the above painting, Allegory of the Plague, from the 15th century, the artist portrays the disease as a winged black figure, possibly an angel, riding a black horse. The Plague is depicted as taking aim at its victims and shooting them with an arrow. The winged figure also carries a sickle, which is a symbol associated with death.

Plague in Rome by Delaunay was one of the most acclaimed works in the Salon in Paris in 1869; the artist was inspired by a fresco from 1476 that he had seen in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli, depicting a plague epidemic.

The painting recalls a passage from Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend telling the story of Saint Sebastian and shows a good angel who commands a bad angel in a black robe, armed with a pike. The bad angel strikes the houses and each house has as many deaths as the number of blows on the door.

The Symbolist Arnold Böcklin had an obsession with nightmares, death, and darkness. The artist was interested in the pestilence and he depicted it as a disturbing figure in black clothing riding a dragon-like creature.

However, the symptoms of the Plague were fever, chills, swelling, and spots of various colors, but not a black body. So why do we call it the Black Death?

The most likely explanation for this is a mistranslation made by Swedish and Danish chroniclers, that the German doctor J.F.K Hecker recalled in the 18th century. Hecker wrote an article about the Pestilence titled The Black Death that was later translated into various languages.

So, that’s how a simple name born from a mistake in translation has struck artists’ imaginations for centuries.

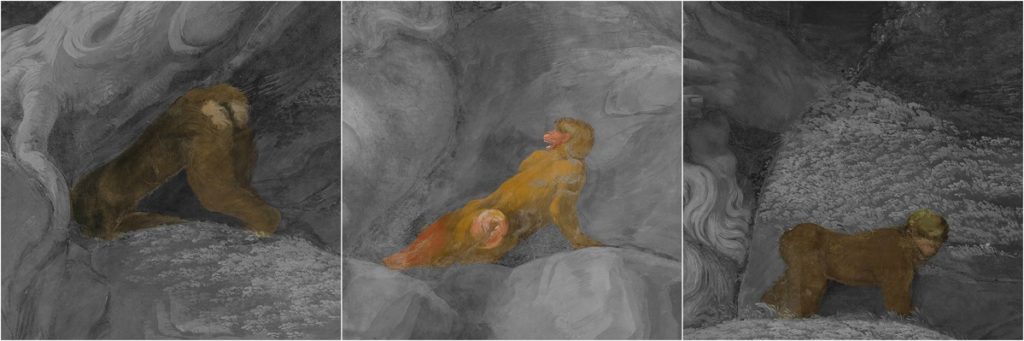

Palazzo Te is a palace in the suburbs of Mantua, Italy, built between 1524 and 1534, and it is Giulio Romano’s architectural masterpiece. The rooms of the palace are wonderfully frescoed and represent myths, symbols of Roman art, and paganism. The most extraordinary room is the so-called Chamber of the Giants, where the artist portrays the story of the Fall of the Giants. This story is based upon the Latin poem The Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid.

Romano gives us the illusion that there is no space or time but the story and is able to throw us right into the action. He represents the moment when Zeus gathers all the other gods together and punishes the insurgent giants who tried to storm Mount Olympus.

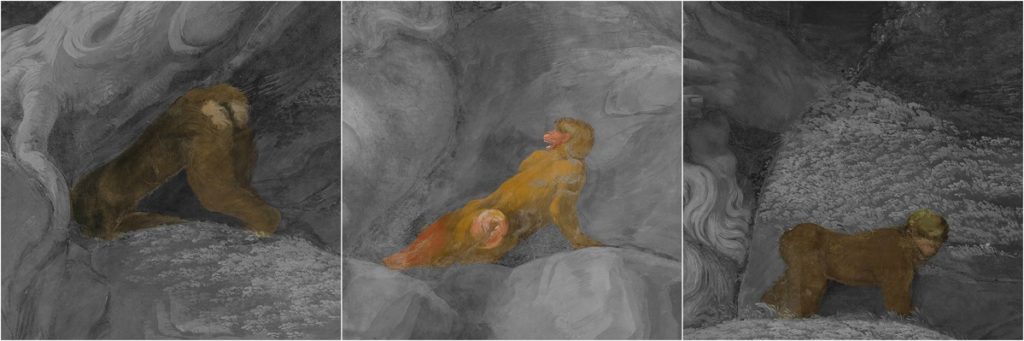

If you look carefully, you’ll notice that there are several monkeys on the rocks and the giants’ corpses. But what you may not understand is what the monkeys have to do with gods and giants.

Well, according to an accurate philological edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, it states that the second generation of mankind was born from the blood of the fallen giants; one of the verses says “scires e sanguine natos“, meaning “you’d know (those generations) were born from blood.”

It appears that in Romano’s copy of Metamorphoses, this translation was incorrect; in fact, that same verse said “scimies e sanguine natos“, meaning “monkeys born from blood.” Another artist tricked by the complex art of translation!

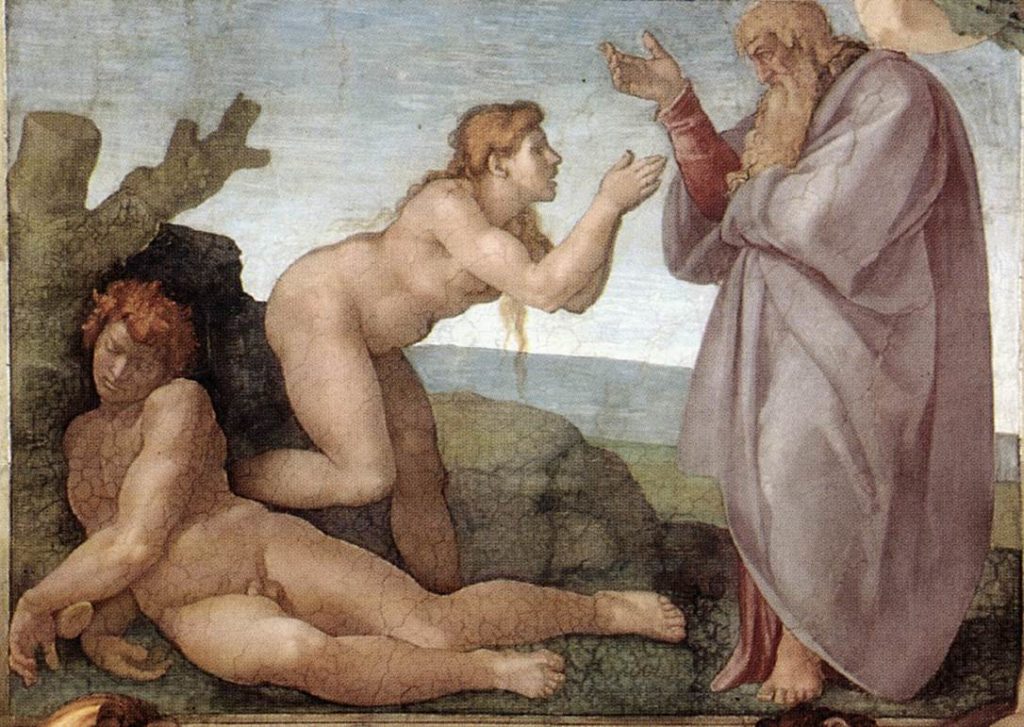

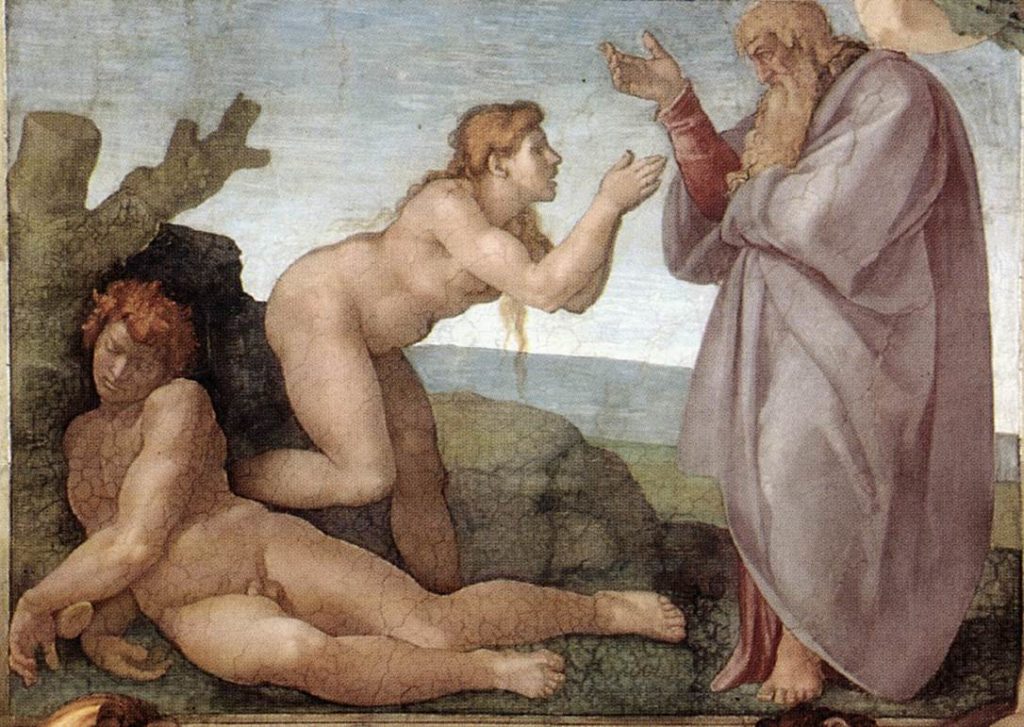

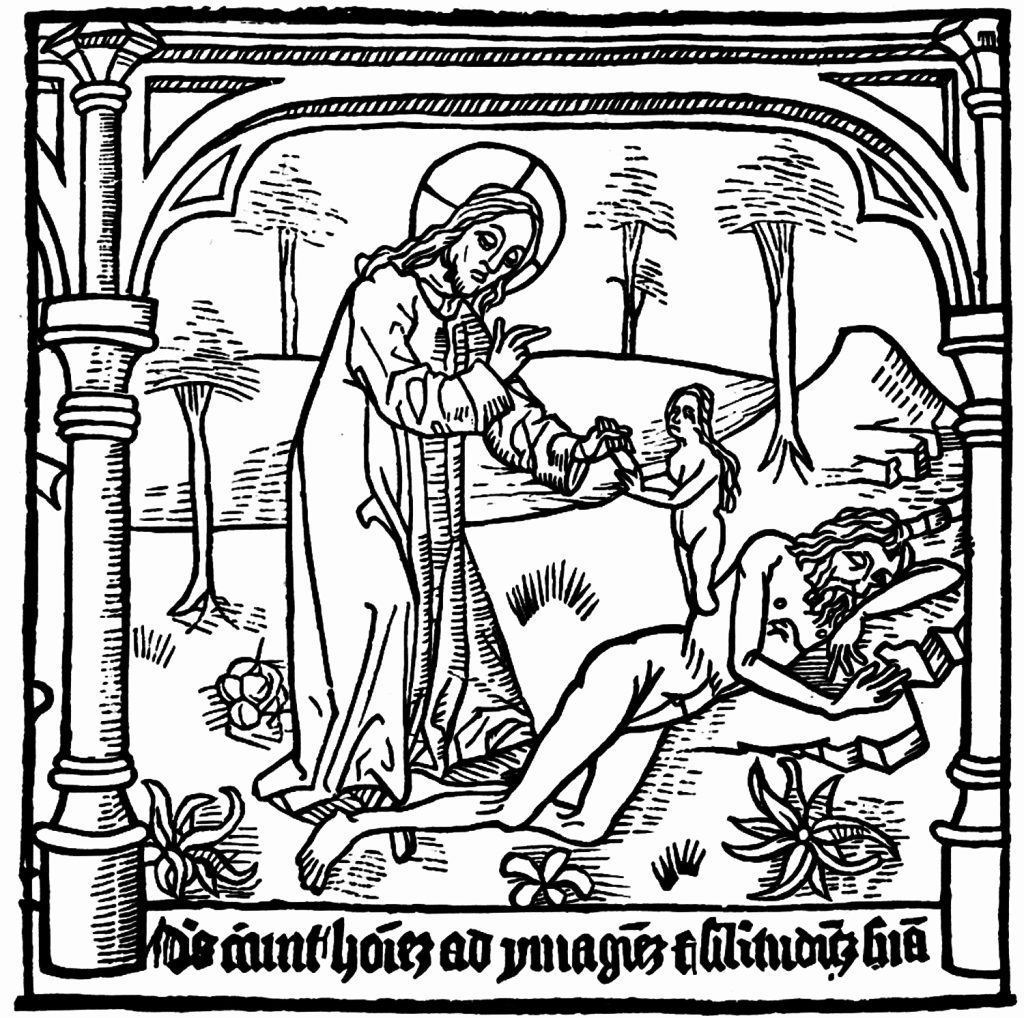

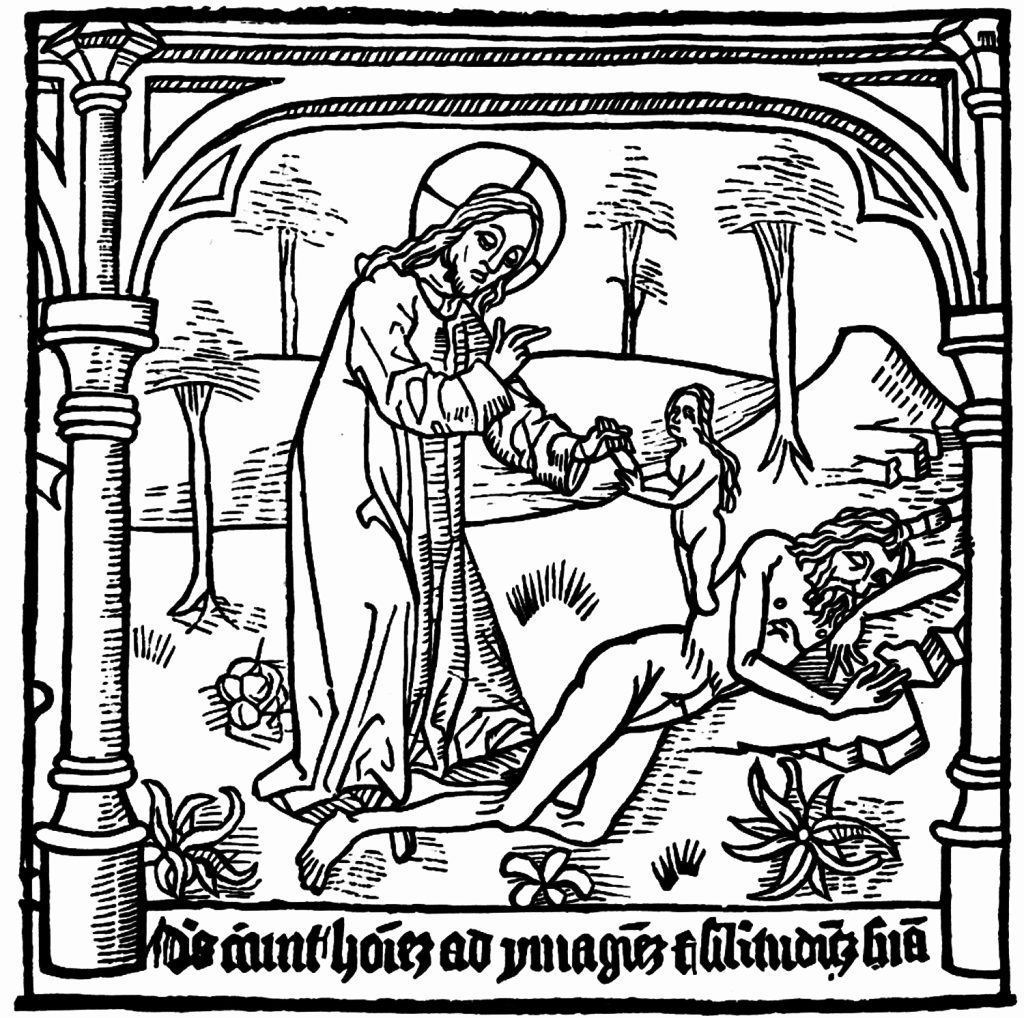

In art history, there are many artworks of different kinds that describe the story of the creation of the first woman, Eve, according to the Christian religion. The most famous representation of Eve’s Creation is Michelangelo’s, which is a fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But there are many others that take the form of paintings, bas-reliefs, and engravings.

Each one of these artworks shows the same scene: God welcoming Eve after creating her from Adam’s rib. The artists portrayed the story in this way because of the biblical passage in the Book of Genesis. However, this is not a very flattering view of women. As they are depicted as being an appendage of man, and condemned to a subordinate role from the very beginning.

However, women of the world, do not worry! Because this story is based on a mistake made by the translators that lasted for centuries. In fact, the Hebrew word for “rib” is tselah, and that can also mean “side” or “half”. This word appears 49 times in the Bible with the meaning being “half”, and just once with the meaning being “rib”; only in the verses that describe Eve’s Creation.

The correct version of the story would put men and women at the same level and in an equal relationship. And if it had been that version that had been passed down through the centuries, maybe today the world would be a little bit different…

The Nativity of Jesus has always been one of the favorite subjects of Christian art, and it was especially so, in Italy between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. However, it also appears at the end of the 19th century during the Symbolist period after losing its sacred meaning and becoming a symbol of maternity.

Every artist has their own style and ways of depicting the holy scene: from Giotto’s and Fra Angelico‘s representations, which evoke a simpler and classic iconography, all the way through to the rich and sumptuous styles of Domenico Ghirlandaio and Sandro Botticelli.

The first artists to depict the scenes of the Nativity of Jesus painted almost word for word what they had read or knew about it from the Bible. The usual representation portrayed baby Jesus with Mary and Joseph, and the ox and the donkey with the angels above.

I am guessing that you may have thought that the reason there is an ox and a donkey present in every Nativity scene is because Mary gave birth to Jesus in a barn. It seems reasonable, but the truth is that they only exist because of a mistake in the translation.

The four Gospels never mentioned these animals; we can only find them in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, which is apocryphal. In other words, it is not one of the recognized sacred texts. Chapter 14 of the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew reads:

And on the third day after the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ, the most blessed Mary went forth out of the cave, and entering a stable, placed the child in the stall, and the ox and the ass adored Him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by Isaiah the prophet, saying: The ox knows his owner, and the ass his master’s crib. Isaiah 1:3 The very animals, therefore, the ox and the ass, having Him in their midst, incessantly adored Him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by Abacuc the prophet saying: Between two animals you are made manifest. In the same place Joseph remained with Mary three days.

Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, 14

There are two big mistakes here. The first is about Isaiah’s prophecy, which has actually nothing to do with the birth. It was the prophet complaining that Israel doesn’t recognize and acknowledge its God anymore, whereas even animals are able to recognize their owner.

The second error is about Abacuc’s prophecy, which was mistranslated. In fact, someone translated the phrase “between two animals” in Latin as in medio duorum animalium, but the original Greek expression was different. The translator must have confused the plural genitive of the Greek word zoé, meaning “ages”, for the Greek word zoon‘s one, meaning “animals”.

That’s why this mistranslated prophecy, which probably meant that Jesus would have been a break between two ages, has imprinted these two cute animals on the collective imagination.

You can see now how a simple mistake causes a chain of errors that can change not only art history but also our traditions and our society. That is why the work of philologists and translators is so important, and we shouldn’t underestimate it.

If you want to know more about this topic, I highly recommend 111 Translation Mistakes That Changed the World by Romolo Giovanni Capuano. It has inspired this article and it may change your world!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!