10 Romanesque Art Treasures from Barcelona

Barcelona = Gaudí, we all know that. For football fans, it is also the famous Barça, the team with the motto: “More than a club”. And so it is...

Joanna Kaszubowska 7 November 2024

9 January 2025 min Read

The Middle Ages have a very sketchy reputation. On one hand, we know that a lot of amazing art was created during that time. On the other hand, there’s this lingering notion that the Middle Ages were a gloomy valley between the cultural peaks of antiquity and Renaisance. A lot of it has to do with our anthropocentric worldview, which is very different from the values that ruled the Middle Ages. But it takes only a brief look to completely dismiss the idea of the Middle Ages being, in any way, a “worse” time for culture. Today we’ll take a closer look at one of the world’s most famous manuscripts, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, or The Very Rich Hours of Duke of Berry, fancy title isn’t it?

Books of hours are probably the most common type of manuscripts that survived from the Middle Ages until our times. This is because they were also the ones that were most frequently ordered. But what is a book of hours, really? The hours refer to canonical hours, which mark the fixed time of prayers during the day, associated with specific religious topics. A book of hours is a book containing such prayers and psalms to help people practice devotion at home. In a monastery, a full breviary would be used for such a purpose, but a book of hours can be considered a “pocket version” of the breviary. Given the cost of such richly illuminated manuscripts, those pockets would have to be sufficiently deep, of course.

The Duke of Berry certainly believed he possessed pockets deep enough, but after his death, some of his creditors begged to differ. John, Duke of Berry, or Jean de Berry, in his native language, was the third son of John II, the King of France. While he may have had a very rich life, what he is most remembered for is his fondness for manuscripts. Apart from the Très Riches Heures, he also possessed Petites Heures, Belles Heures, and Turin-Milan Heures, among others. His estate also included many castles, some of which you’ll see in the illuminations used in this text. Sadly, when Jean de Berry died, it became obvious that he lived above his means and his estate was heavily in debt, resulting in the sale of many of the manuscripts.

Given De Berry’s passion, it is understandable that he would be the patron of the Limbourg brothers. They seem to have been bound so close by the work they did that we know them collectively as Limbourg brothers, but they actually had names: Paul, Jean, and Herman. They originated from Nijmegen in today’s Netherlands. Their early life was a very turbulent period and included an apprenticeship in Paris cut short by the plague and being imprisoned in Brussels for ransom. Then, their first major patron (Jean de Berry’s brother Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy) died in 1404, and finally, the brothers found a new home under the wing of Jean de Berry.

Their first commission for the Duke was the Belles Heures—the only manuscript they completed for him. After that, they started work on Très Riches Heures, but it was interrupted by their and their patron’s untimely death in 1416, most probably of plague.

When the Duke and his artists died, the Duke’s estate was auctioned to cover the cost of his lavish lifestyle, including the unfinished manuscript. However, the fate of the manuscript between 1416 and 1485 is unknown. In 1485, it was acquired by Charles I of Savoy, who commissioned Jean Colombe to finish the work. Judging by the style of the miniatures and the clothing of people presented in them, it is also broadly agreed that there is evidence of the hand of an ‘intermediate painter.’

This text is illustrated with the labors of the months, but the illuminations mostly focus on religious topics, as befits a prayer book. So, the most commonly known works from Très Riches Heures are actually outliers. Nonetheless, their mastery cannot be denied; the attention to detail is striking.

Surprisingly, the book was not broadly known until the 19th century, and the Limbourg brothers were completely forgotten. In 1856, Henri d’Orléans, Duke of Aumale, bought the book from Baron Felix de Margherita of Turin and Milan (the longish aristocratic titles always make me grin, I just cannot help myself). He connected the dots and identified the book as a commission of De Berry and used his contacts in the art history world to popularize it.

The original is now in the Musée Condé, heavily protected and almost never shown to the public. Instead, a modern facsimile is presented both to tourists and academic visitors.

As usually is the case with art, the key is in looking at them not reading about them. I’ll just briefly describe each month, so you can focus on closely looking at each miniature.

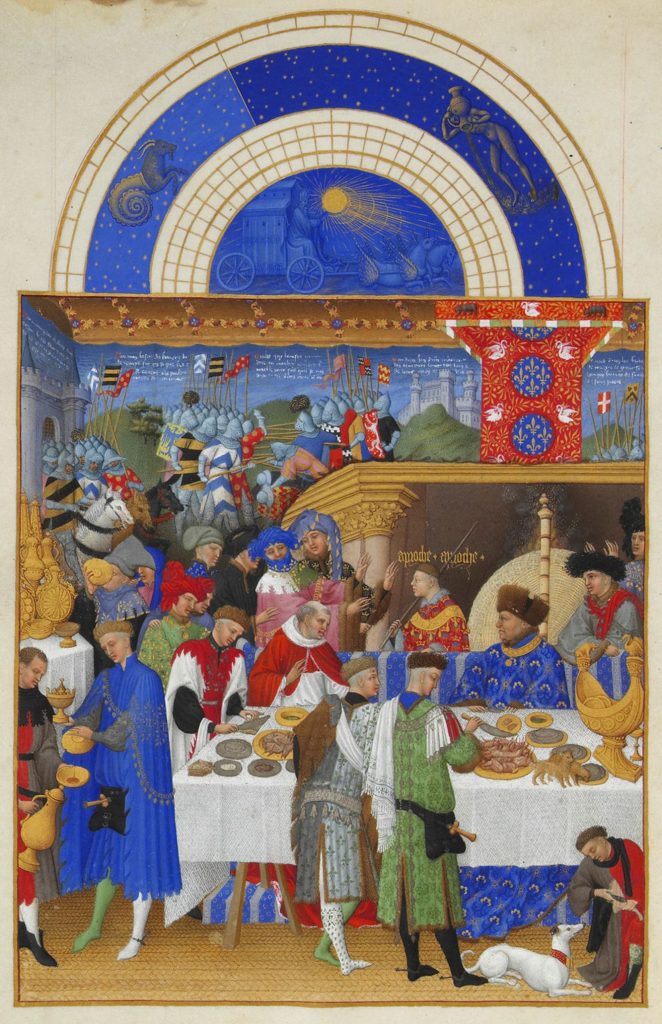

In January we see a traditional New Year’s feast with the exchange of gifts. You can see Jean de Berry, sitting at the table in a lavish blue coat with a heavy winter hat. It is also worth noticing that the battle scene in the background is a tapestry.

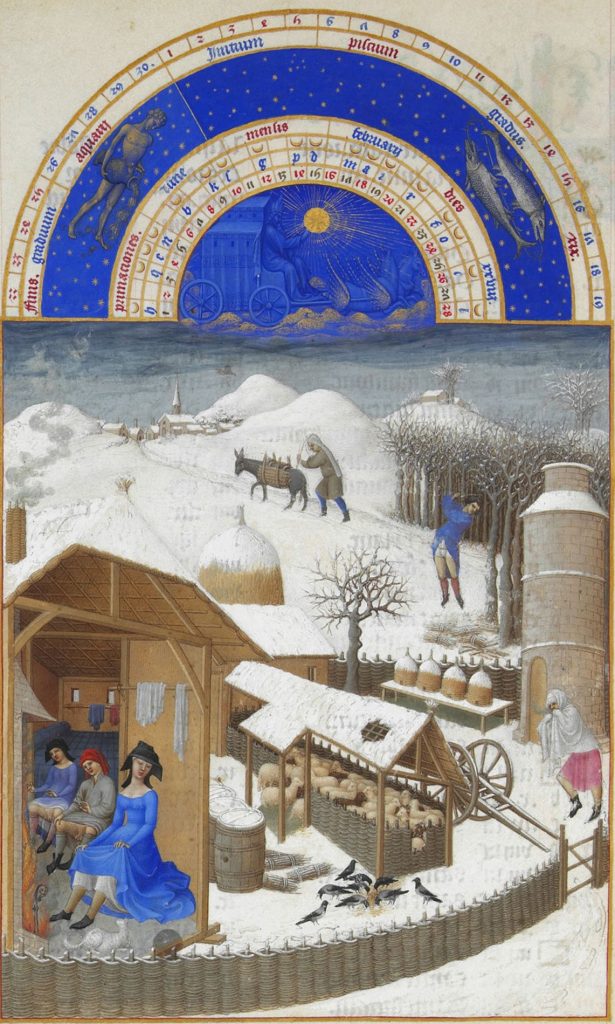

February is my favorite for its tiny naughtiness. The general focus is on staying warm—people collect firewood and wrap themselves, but in the front, we see peasants hiking their clothes to catch the warmth from the fire, and guess what? No underwear! Life magazine retouched the picture when it was published in 1948.

March shows one of De Berry’s castles: Château de Lusignan. We can also see the spring is coming and the peasants prepare the fields and vineyards for it.

April is spring in full bloom—including blooming love—as depicted by the aristocratic betrothal. We can see the friends of the fiancee gathering flowers. What really catches the eye are the fancy hats and hairdos, they are very elaborate.

May is a celebration of spring. Everyone is decorated with garlands, and ladies wear green dresses. The castle in the background is believed to be Palais de la Cite in Paris.

June abandons the aristocratic entertainment and focuses on the hard work of peasants again. We see the harvest, both men and women are involved, but what I found interesting here is how the men are pretty scantily dressed to allow for the hard work in the early summer heat. You can also see how their skin is clearly tanned when compared to the milky white skin of the fully clothed women.

July means more harvest, but you can also see the shearing of the sheep. We even seem to have the same man in a white shirt. But my favorite part is the barely visible—and yet so elegant—swans in the moat. Take a closer look.

August shows us both aristocratic and peasant entertainments. While aristocrats are hawking, the peasants in the background are skinny dipping in the river. The way the silhouettes in the water are distorted brings to mind the devils from some of the depictions of medieval hell.

September is the time of the grape harvest. The key two figures here are the sneaky eater and the diligent picker in a too-short shirt. Surprisingly, this time, unlike in February, we see the underwear.

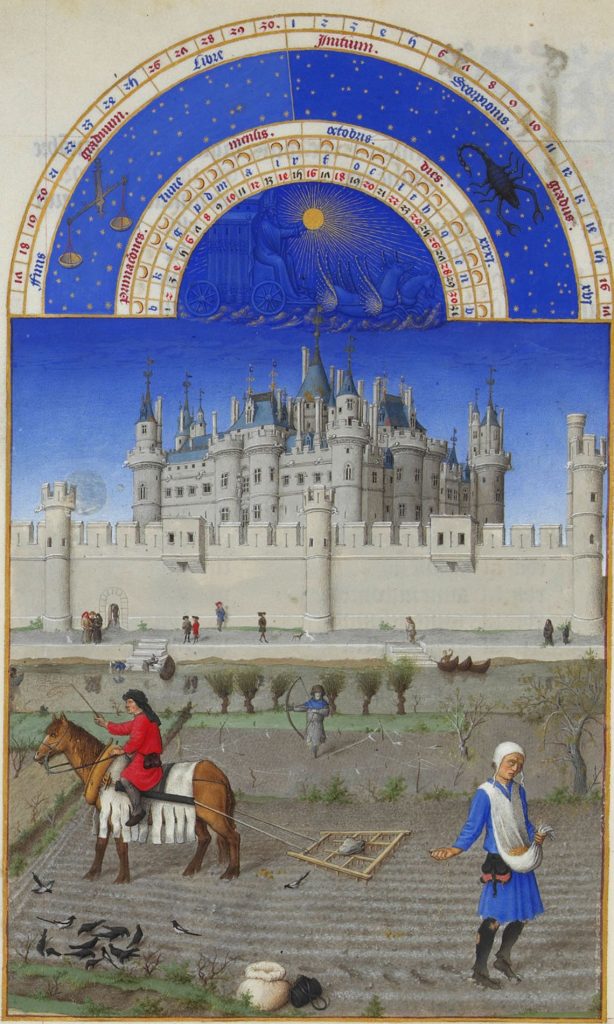

October is the time to prepare the fields for winter. The guy sowing the seeds clearly is fed up with his work. However, the figure in the center is more interesting—here we get to see a medieval scarecrow.

November is the time of acorn harvest. Acorns were important as the feed for pigs. Apparently, they can also be eaten by people. You can find out more here if you’d like to try something new.

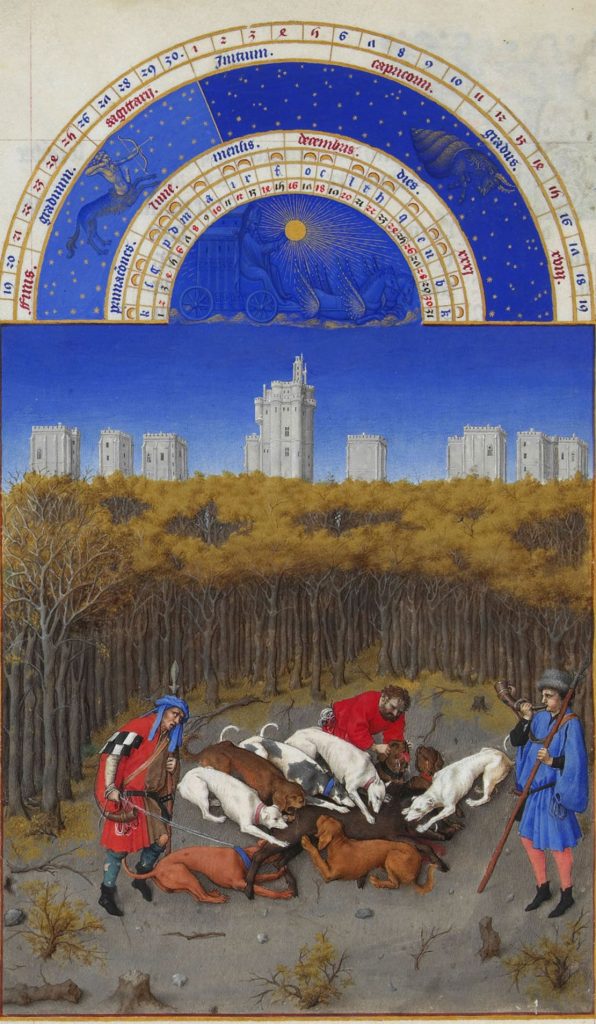

December makes you look a bit more suspiciously at your puppy. The dogs viciously attack the board during the hunt. I’m not sure if the guy in the red shirt is petting the dog or trying to pull it away.

As you can see, the Très Riches Heures really are very rich indeed. The level of detail and vividness of colors is striking. They are also a cultural document, providing us with visual information about life in the late Middle Ages. The facsimile of this book of hours is available online here.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!