Summary

- Katsushika Hokusai was a Japanese printmaker who revolutionized the ukiyo-e style. Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji was his most famous series showcasing his mastery of composition.

- The Great Wave was influenced by Dutch depictions of the sea, a topic that was not popular in Japan at the time.

- Through his well-thought-out composition, The Great Wave can be understood as the “opening” of Japan to the West and a promise of a brighter future for the country.

- One of the reasons behind the success of the series was Prussian blue, a new pigment that reached Japan in the early 19th century.

- The Great Wave was so successful that it has inspired Western art including Vincent van Gogh and other Post-Impressionists, musicians, and even contemporary internet creators.

Hokusai’s New Wave

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) was a Japanese artist, painter, and printmaker who was born in Edo, modern-day Tokyo. Hokusai began painting around the age of six, possibly learning from his father. Initially, in his teenage years, he worked as an apprentice to an engraver. But then, he entered the studio of Katsukawa Shunsho, a leading artist and printmaker.

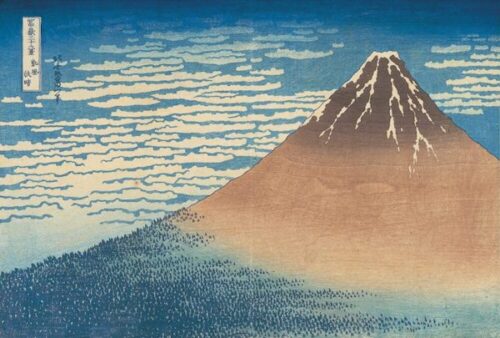

During his career, Hokusai produced thousands of images. In particular, he made ukiyo-e or floating world pictures popular in the Edo period (1603-1868). Meanwhile, other artists of this genre largely focused on portraying courtesans and actors. Hokusai transformed ukiyo-e into a much broader style of art. For example, he created Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, a series of landscape prints. This depicts Mount Fuji from different locations and in various seasons and weather conditions.

Katsushika Hokusai, Fine Wind, Clear Morning, from Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1830-1832, Shimane Art Museum, Matsue, Japan.

Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji

The artist used woodcut blocks to make thousands of impressions of his artworks. After their publication, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji became an instant success. Consequently, Hokusai added another ten images, resulting in forty-six prints in the series. They show us that Hokusai was a master in composition. Looking at one of Hokusai’s prints, Kajikazawa in Kai Province, we see how the repetition of shapes and colors unifies the design.

Katsushika Hokusai, Kajikazawa in Kai Province, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1830-1832, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

The fishing lines, the fisherman’s back, and the cliff from which he fishes form the triangular shape. It echoes that of Fuji on the horizon. In addition, the vertical fishing lines and steep Mount Fuji contrast with the horizontal. The lines of the sea contribute further to the dynamism of the image. Moreover, the deep Berlin blue coloration in the foreground and background enhances the visual relationship between man and nature.

Under the Wave off Kanagawa

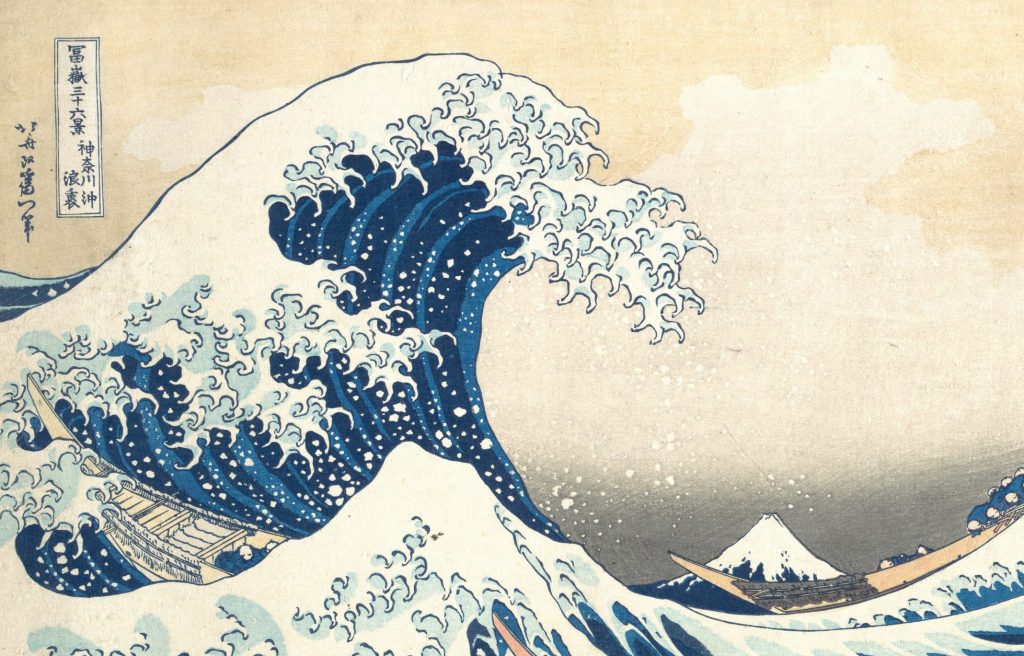

By showing the relationship between man and nature, Hokusai created designs that proved commercially successful. However, it is not a coincidence that Under the Wave off Kanagawa, one of the prints from the series, became more recognizable than others. It is known simply as the Great Wave. It portrays a rogue wave menacing three boats off the coast while Mount Fuji rises in the background.

Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1830-1832, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Hokusai drew inspiration from a real place in Sagami Bay, Kanagawa prefecture. This was a seaside spot with great waves. At the same time, a domestic travel boom could have played a part in the recognition of his prints. In this work, Hokusai also exploits the rise in popularity within Japan for the Western style of painting.

Under the Dutch Wave

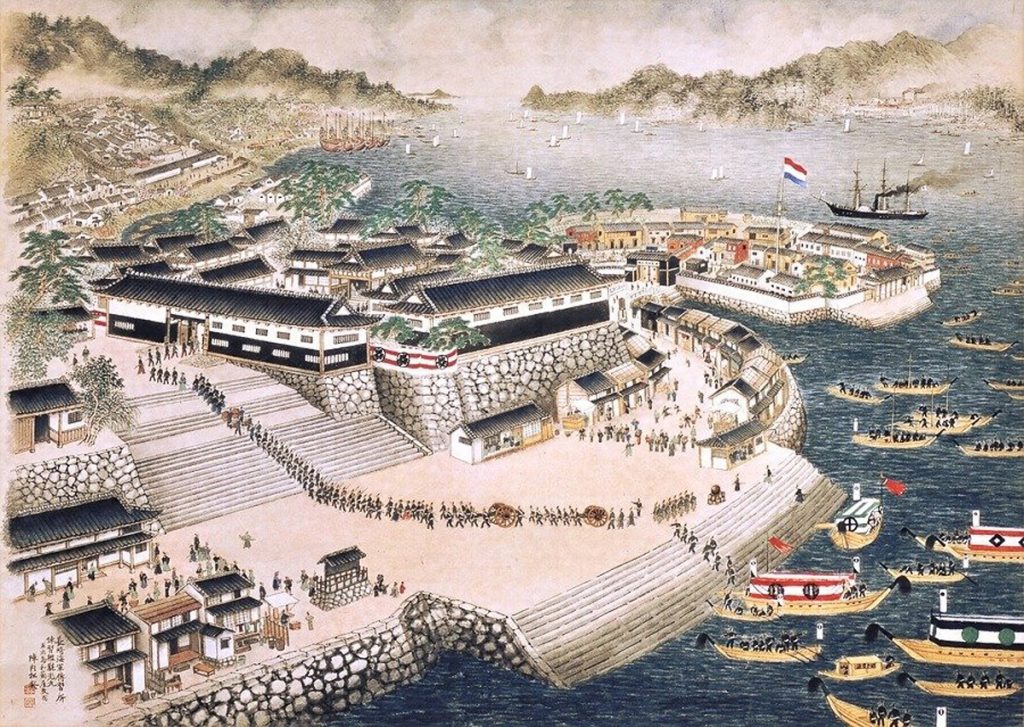

At that time Japan had severely limited European influence and contacts. This had resulted from the 1633 enactment of sakoku or its isolationist foreign policy. Nevertheless, starting from this period Japan traded with China. In effect, the only European influence permitted was the Dutch factory at Dejima in Nagasaki.

Nabeshima Hofukai, Nagasaki Naval Training Centre, 1860-1863, Japan. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Consequently, western scientific, technical, and medical innovations entered Japan through rangaku or “Dutch learning”. This isolationist period ended after 1853. This was the time when American ships forced the opening of Japan to American trade through a series of treaties.

Riding Out a Storm

Hokusai likely studied imported Dutch prints showing ships in stormy seas. One of the artists, the prints of whose paintings probably reached Japan was Ludolf Bakhuizen (1630-1708), also spelled as Backhuysen. His painting Dutch Merchant – Ships in a Storm shows a merchantman and a protective convoy ship riding out a storm. However, it does not illustrate the story of a particular ship. It is a scene picturing stormy marine weather to evoke the fight between man and nature.

Ludolf Bakhuizen (Backhuysen), Dutch Merchant – Ships in a Storm, 1670-1690, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK.

In fact, Bakhuizen often went to the sea in an open boat to study the effects of storms. As a result, his compositions are marked by intense realism and faithful imitation of nature. In his later years, he used his skills in etching.

Ludolf Bakhuizen (Backhuysen), Schip in een ruige zee (Ship in a rough sea), 1701, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

For some time, Japan had only limited contact with other peoples and cultures. Therefore, the Japanese looked at the sea with fear and awe. In contrast, Europeans increased their exploration, having a romantic view of the sea. Consequently, there was a difference in the depiction of the sea in Japanese and Western art.

Rowing Through the Waves

Inspired by the Dutch prints, Hokusai produced multiple images of ships in stormy seas. Other artists usually depicted a series of undulating waves. Conversely, Hokusai made one wave more prominent than others. For example, one of his earlier prints looks similar to the print Under the Wave off Kanagawa. It has a horizontal format, a brown and green color scheme, and a decorative frame. This was in keeping with the convention of Dutch engravings at that time.

Katsushika Hokusai, Express Delivery Boats Rowing through Waves, ca. 1800-1805, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

Meeting the Great Wave

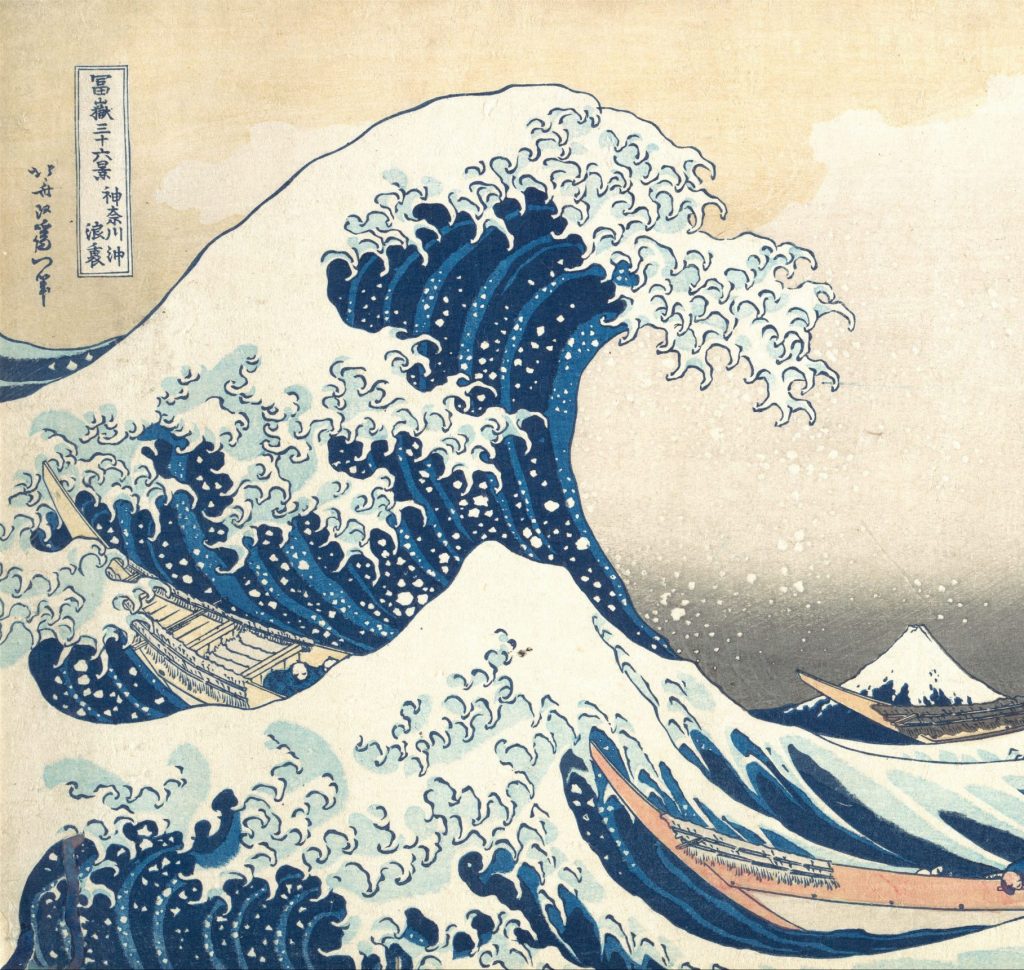

Still, in this earlier print, two waves appear distanced and generalized. In 1831, Hokusai reinterpreted his image. He depicted one big wave with a claw-like crest swallowing up the boat. The splashes of water, look like snow; they bombard the boatmen. Inevitably, the wave attracts our attention, creating the immediacy of experience. Considering the size of the fishing boats, the rogue wave could be 32 to 39 feet (about 9-12 meters) in height. In addition, the low, water-level viewpoint augments the effect of the image. However, the smaller wave appearing in front of the great wave, undermines its threat.

Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1830-1832, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

For the Japanese viewer, the left-to-right direction of the wave was likely to have been interpreted as unusual. This style of writing, identical to that of European languages, is known as yokogaki. As in Chinese traditional painting, Japanese prints and inscriptions were usually read from right to left. Thus, this arrangement could indicate the interaction and dialogue with the West. The uncertain fate of the boats facing the power of the wave reveals the dangers such relations could entail.

Reaching Mount Fuji

Furthermore, Hokusai added Mount Fuji, a feature that became the unifying theme in his series. Located on Honshu Island, it is the highest mountain in Japan. It has a connection with the soul of Japan, serving as the idea of Japan itself. In fact, Mount Fuji has inspired many artists and is often visited by sightseers and climbers.

Katsushika Hokusai, Tago Bay near Ejiri on the Tokaido, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1830-1832, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

In his print Under the Wave off Kanagawa, Hokusai used the principles of perspective and pushed Mount Fuji into the distance. The perspective could signify a window on the world, understood metaphorically as a larger “opening” of Japan. The waves form a frame through which we see the mountain. Indeed, the small wave has a similar shape to the silhouette of Mount Fuji. Thus, Hokusai employed a similar principle as in his Kajikazawa in Kai Province with the fisherman.

Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1830-1832, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Detail.

Mount Fuji, an active stratovolcano, was deemed immortal. Here it fixes the big wave which becomes static rather than fluid and ephemeral. Its symmetrical cone adds certain stability to the image. Nevertheless, the great wave offsets it and creates suspense. We start to wonder about the fate of the boatmen and the subsequent course of events. Is Mount Fuji, which appears small in comparison, about to be consumed by the rogue wave or, metaphorically, foreign forces? It is as though the wave can reach out and seize it.

Diving into the Deep Blue

Because of the dominant waves and sea, the deep blue color permeates the print. However, this is not a Japanese blue but is Prussian or Berlin blue. This was probably first synthesized by Johann Jacob Diesbach in Berlin around 1706. The dye was then imported into Japan either by Dutch traders or via China, where it was manufactured from the 1820s.

The public admired the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji partly because of this beautiful blue, prized due to its foreignness. Therefore, the Great Wave is not the perfect example of a typical Japanese print. Instead, the image blends European materials, principles of perspective used in the West, and Japanese aesthetics. Hokusai seems to have mixed feelings about the sea over which the European technologies and ideas have traveled. Thus, the waves and sea could represent the possibility of bridging with the West and its dangers.

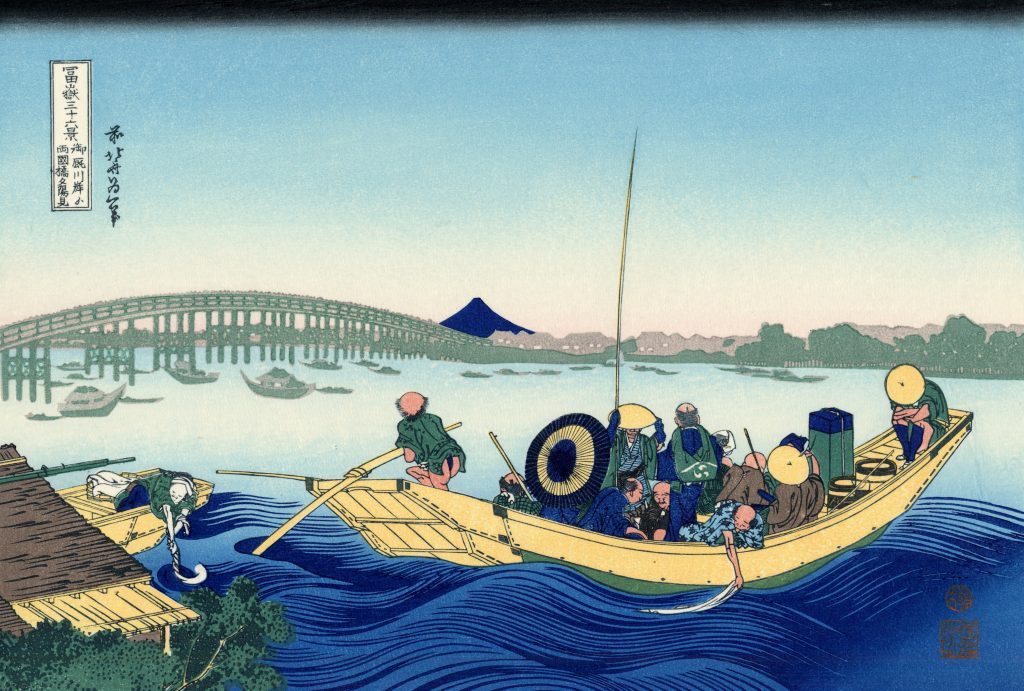

Katsushika Hokusai, Viewing the Sunset over Ryogoku Bridge from the Onmayagashi Embankment, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1830-1832, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

At the same time, the waves could symbolize the potential to travel abroad, to find new things outside Japan. Breaking down the barriers could imply a new interest in the world. By oversizing the wave, Hokusai showed the consequences of the flow of people and goods across the seas. With the clear sky in the distance, his Great Wave offered the promise of a brighter future resulting from the interaction between the cultures.

Spreading the Wave

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan ended a period of national isolation. Consequently, Japanese art came to the West and quickly gained popularity. Its influence on Western culture became known as Japonisme. In fact, this term was introduced in 1872 by an art critic Philippe Burty (1830-1890). Japanese prints became a source of inspiration for artists in many genres. Van Gogh, Cézanne, Degas, and Manet all praised Hokusai’s art. Without Hokusai’s sense of imagined perspective, Impressionism would probably have taken a different route.

Van Gogh (1853–1890), a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter, described Hokusai’s print:

I did not know that one could be so terrifying with blue and green…these waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it.

Letter to his brother Theo, September 8, 1888.

We can see the influence of the Great Wave in his painting Starry Night. The swirling shapes in the night sky are reminiscent of Hokusai’s wave. Furthermore, the artist also creates his composition almost entirely from shades of Prussian blue with only small amounts of yellow.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1889, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Van Gogh’s Starry Night is based on observation. Yet, in his painting nature diverts from its actual appearance. He also depicted this scene during the day, under different atmospheric conditions. The picturesque village nestling below the hills was based on other views. However, Van Gogh painted the main features of the sky as observed whilst adding a sense of glow by altering the celestial shapes.

Finding the Vantage Point

Heading from the picturesque village to the city, Henri Rivière (1864-1951), a French artist, was also inspired by Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. In a series of lithographs, Rivière was the first artist to investigate the effect of the Eiffel Tower from different vantage points. Erected in 1889 for the Paris Universal Exposition, the Tower reached almost double the height of any other structure yet built. Thus it symbolized modern technology.

Henri Rivière, The Eiffel Tower under construction, seen from the Trocadéro, Thirty-Six Views of the Eiffel Tower, 1902, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

His 36 lithographs, based on drawings he made between 1887 and 1892, depict the Tower from different vantage points. The prints show that the Eiffel Tower was omnipresent within the greater urban landscape of Paris. Indeed, it still maintains its visual dominance over the city today.

Composing La Mer

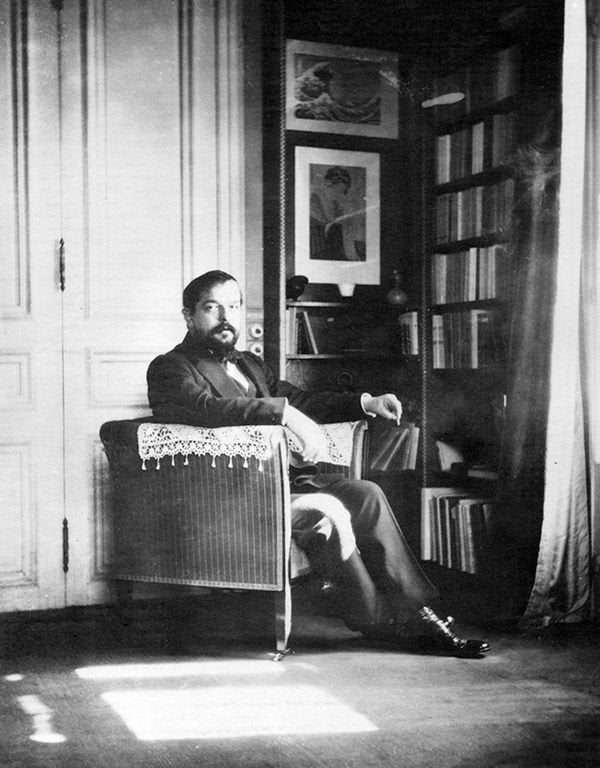

Because of the creative use of composition, the waves were open to interpretation. Consequently, many creative people drew on their recognition of the image. For example, Claude Debussy (1862-1918), a French composer, created his piece La Mer between 1903 and 1905, inspired by Hokusai’s work.

When he was a student in Rome, Debussy often visited the city’s antique shops purchasing Japanese artworks to take back to Paris. He kept many of them in his studio. Amongst them was a framed print of Hokusai’s Great Wave which we can see in this photo. Here Claude Debussy appears with the Great Wave displayed on the rear wall.

Claude Debussy in his Paris studio, 1910, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel, Switzerland.

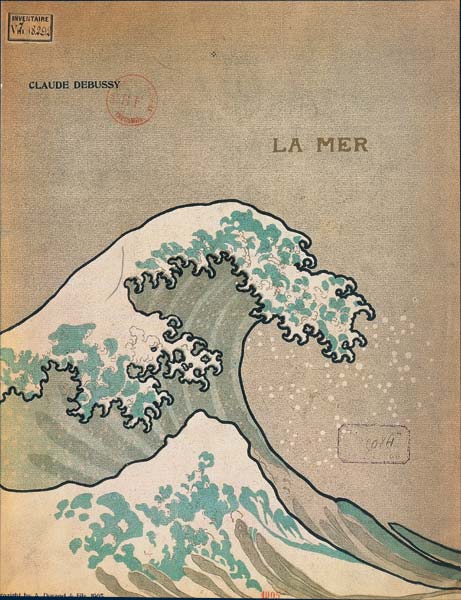

Debussy even used a detail of the Great Wave on the cover of the first edition of La Mer from 1905. The composer took part in choosing the image which was recognizable throughout Western Europe. Debussy could have been implying that his new orchestral score would have the same power, elegance, and color of the work represented on its cover.

Claude Debussy, La Vague d’Hokusai en couverture de La Mer, 1905, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, France. BNF.

Just as Hokusai went beyond convention, so did Debussy who disliked the use of strict musical forms to which other composers adhered. Both Debussy and Hokusai focused on the vibrant energy of the sea. However, Hokusai emphasizes the fear of the water that surrounded his country. In contrast, Debussy permeates his work with a sense of nostalgia for the rest the coast provides.

Riding the Wave

Hokusai’s Great Wave continues to inspire many contemporary artists. One example is Lin Onus (1948–1996), an Australian artist of Scottish-Aboriginal origins. Onus reinterpreted Hokusai’s print by adding a dingo on the back of a stingray riding into the dusty horizon. Both creatures are painted in ivory, red, and black, colors that signify spiritual indigenous motifs.

Lin Onus, Michael and I are just slipping down to the pub for a minute, 1992. Pinterest. Detail.

The dog is juxtaposed with the Great Wave. Thus Onus brings together a scene that emphasizes the differences in individual Australian cultural identity, and the emergence of stereotypes within those dialogues. The painting is meant to symbolize his mother’s and father’s cultures combining in reconciliation.

When we think about Hokusai’s Great Wave, we can see it as his meditation on ideas of identity for both an artist and a nation. Thus, the multiple meanings and the creative composition of the Great Wave made it appealing to a large audience. They also helped to secure its enduring presence in art.

Setting the Wave in Motion

Although the Wave looks static, it feels like it will set in motion within the next second. Watch the animation of the Great Wave and see it in full power.