Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

1 September 2024 min Read

Utagawa Hiroshige’s prints were exported to Europe and became very popular with Western artists. Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh owned approximately 50 of Hiroshige’s landscapes. Van Gogh was quoted saying he tries to view the French countryside with a “Japanese eye” while painting. Hiroshige clearly influenced artists beyond Japan’s isolationist borders, and he became the most prominent Japanese landscape artist of the 19th century.

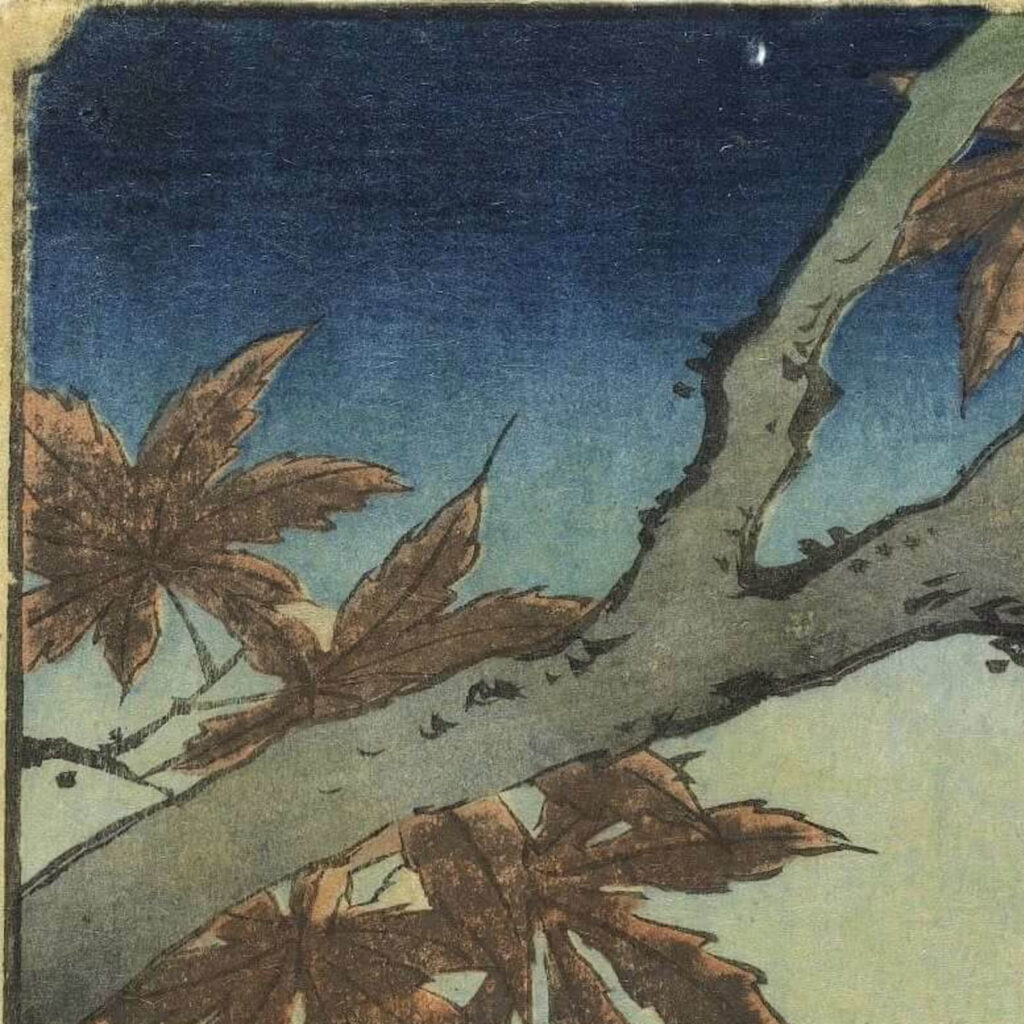

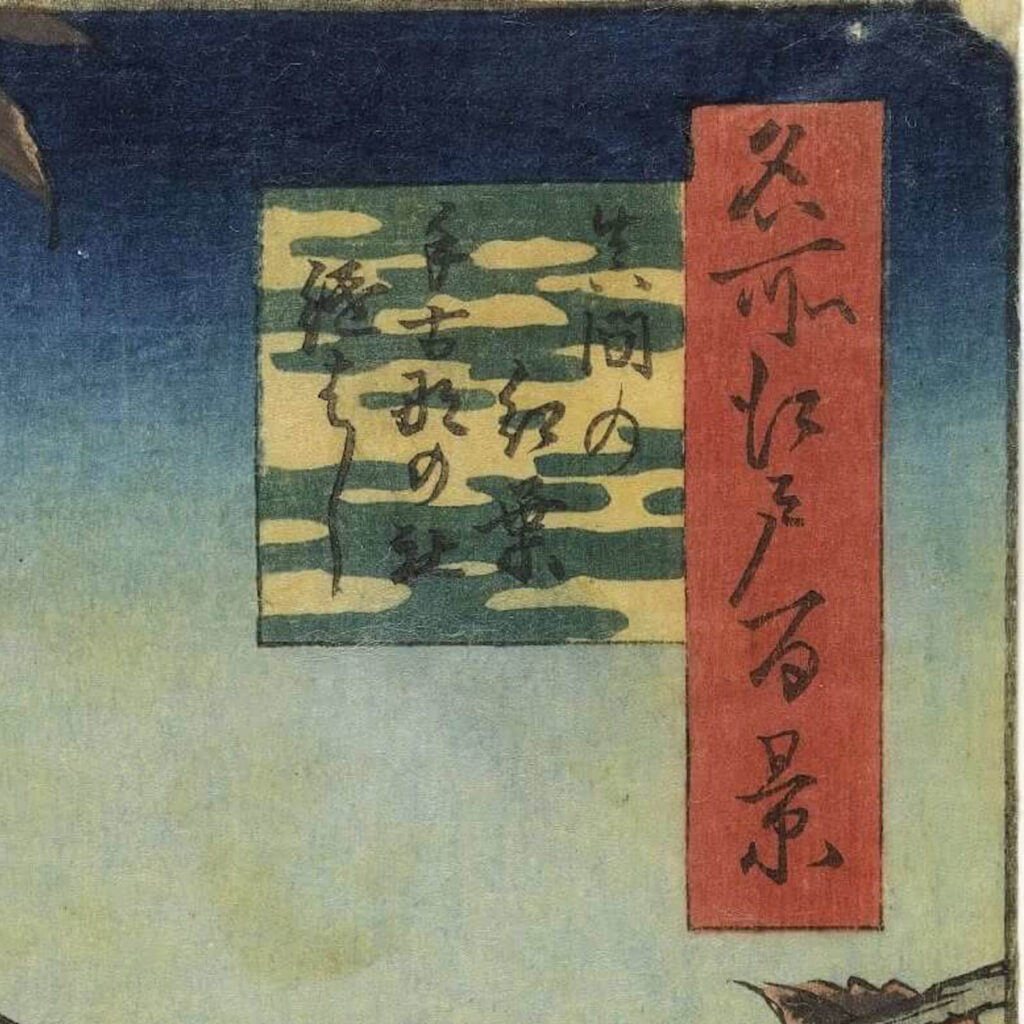

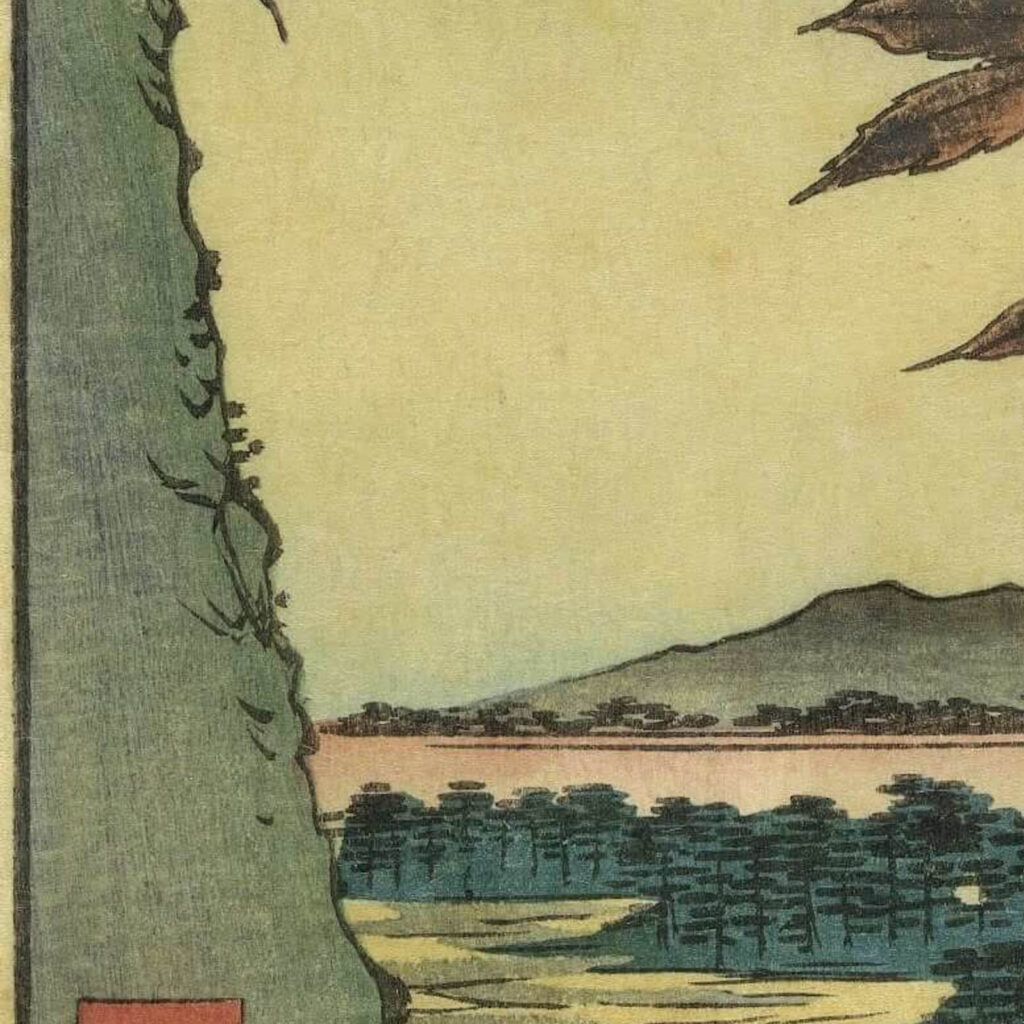

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Museum’s website.

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) lived during the late years of the Edo or Tokugawa Period (1603-1867) when the Tokugawa shogunate ruled Japan from its capital of Edo (modern Tokyo). It was a period of institutionalized xenophobia when Christianity and most Western foreigners were banned. A powerful presence of social stratification and civic responsibility permeated Japanese society. It was amidst this highly regulated society that Hiroshige became the most prominent landscape artist. He was known for the quality and quantity of his colored woodcut prints. One such example is Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge from his series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

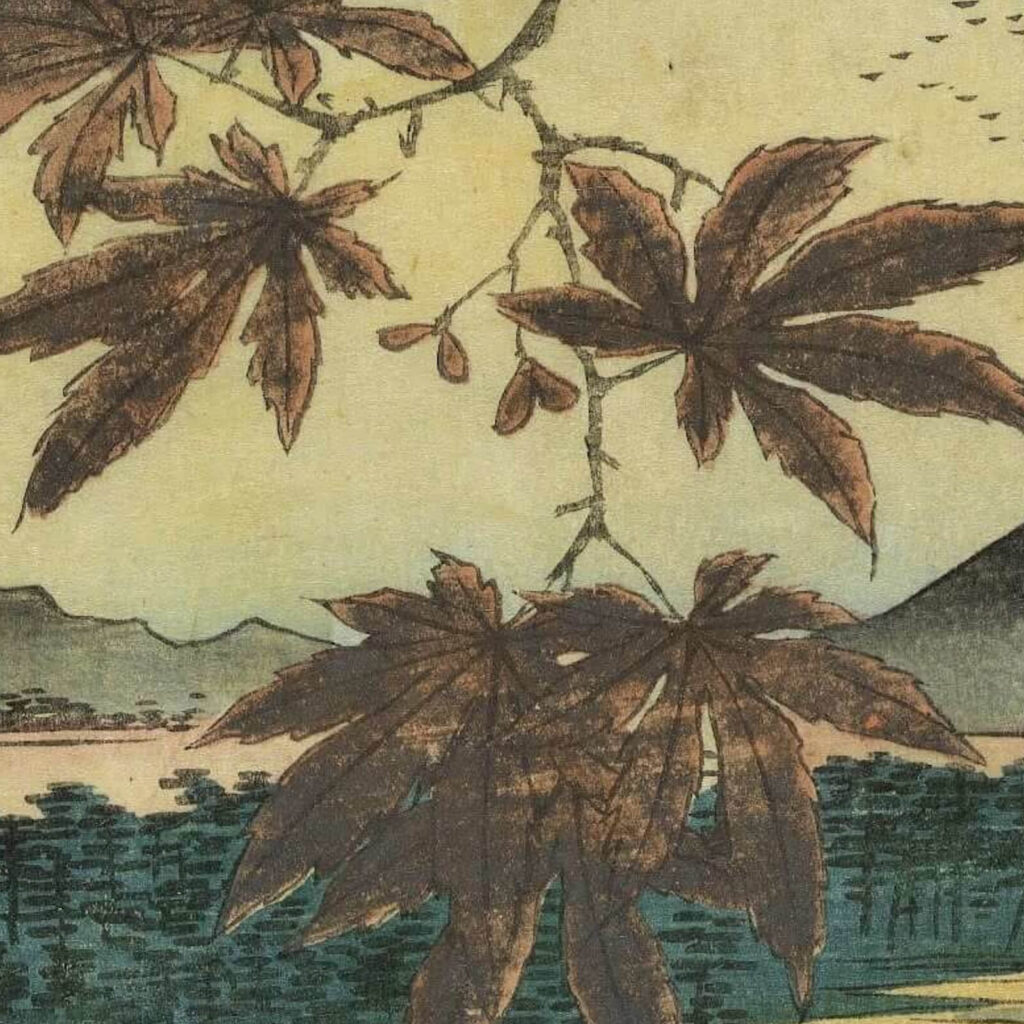

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Utagawa Hiroshige created his colored woodcut prints through a meticulous and methodical process. First, he would draw and design the overall image. Then he, or an assistant, would carve a wooden block matching the design. This block would be duplicated several times so multiple copies would exist. Then each block had a separate ink color applied. These blocks were then pressed against the paper in successive order until all the colored areas were complete. Precision was absolutely paramount as any slippage would result in obviously misaligned colors and lines.

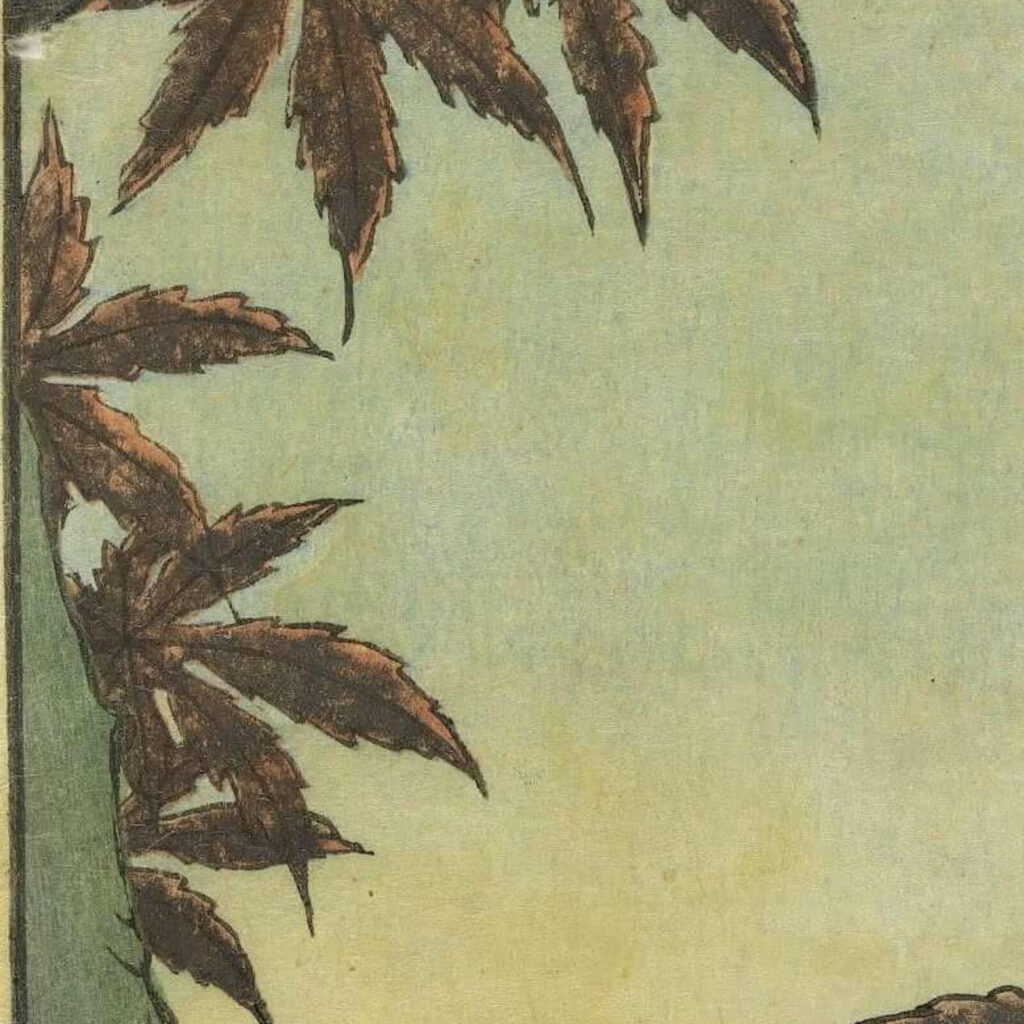

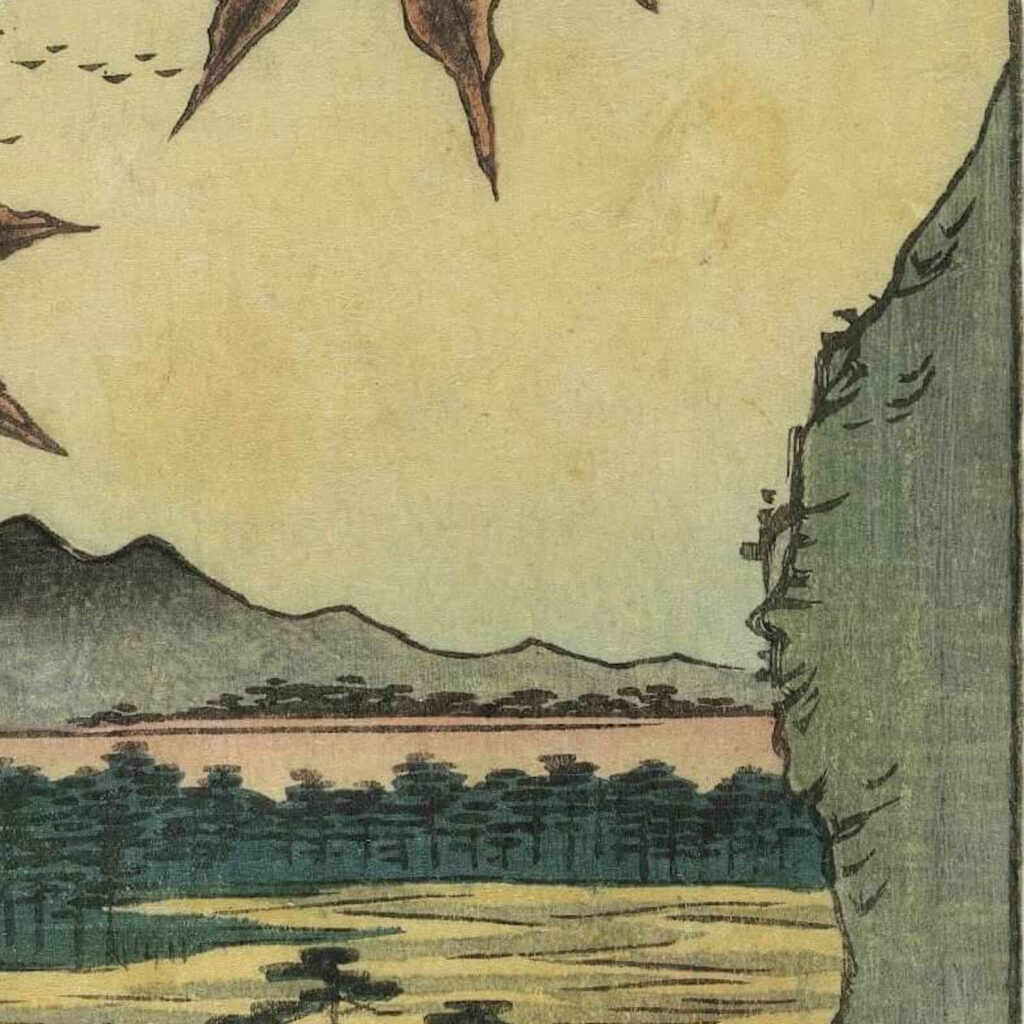

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge was created in January 1857. It is a color woodcut print on paper and measures 8.7 x 13.4 inches (22 x 34 cm). It is a classic example of ukiyo-e which means pictures of the floating world. Ukiyo-e is a Japanese artistic genre that focuses on the transience of human life and the ephemerality of the material world. It was especially popular in the urban culture of Edo where a thriving industry developed in manufacturing ukiyo-e on an industrial scale. Utagawa Hiroshige was part of this commercial industry that mass-produced thousands of woodcuts for each of his designs. Therefore, while Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge is beautiful, it is not unique. Many surviving copies exist. However, its copies do not diminish its artistic value.

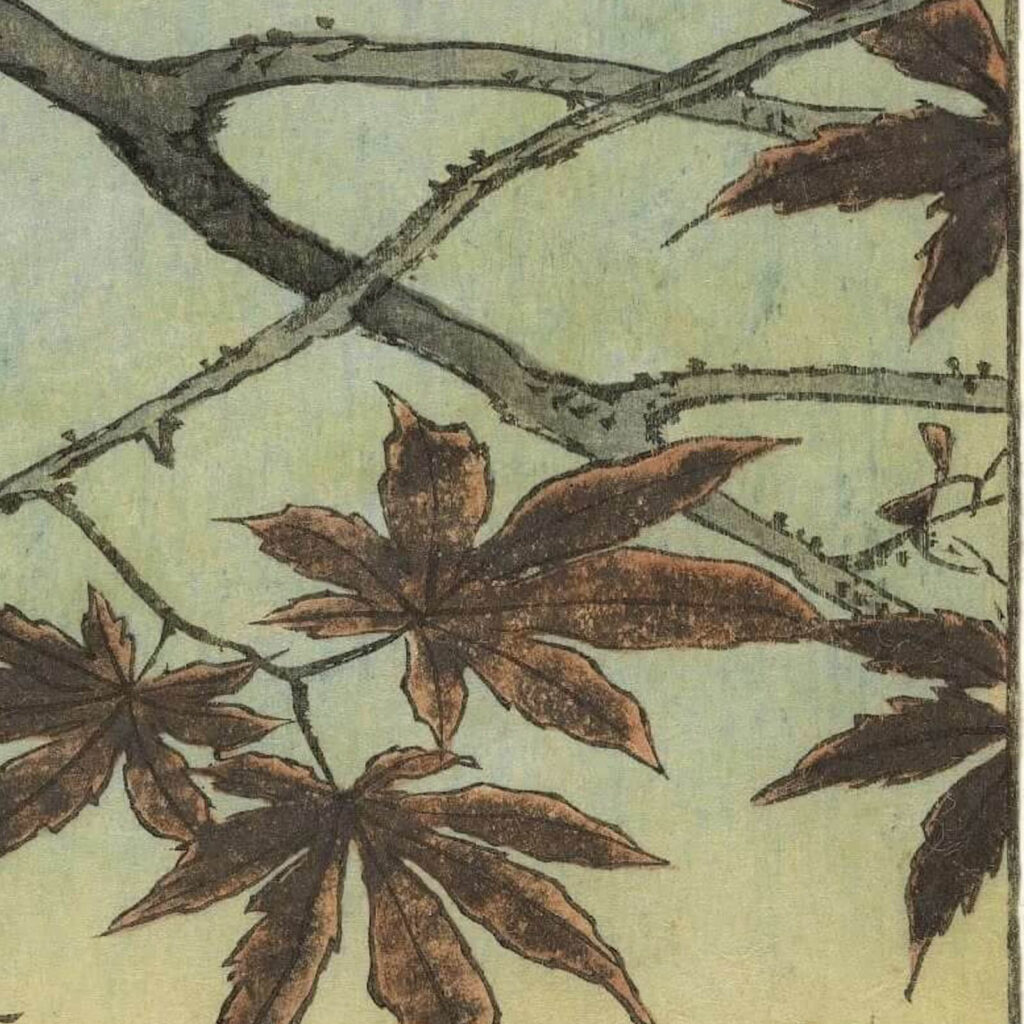

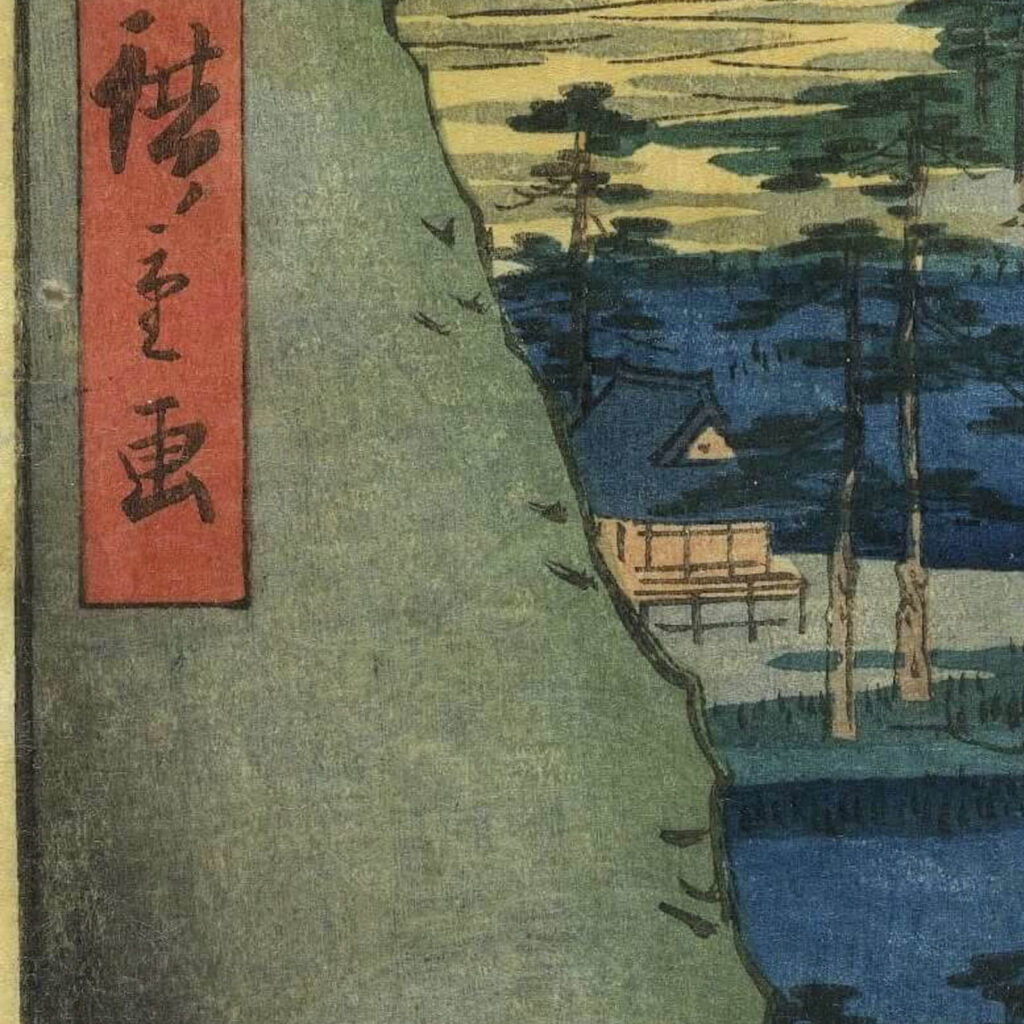

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

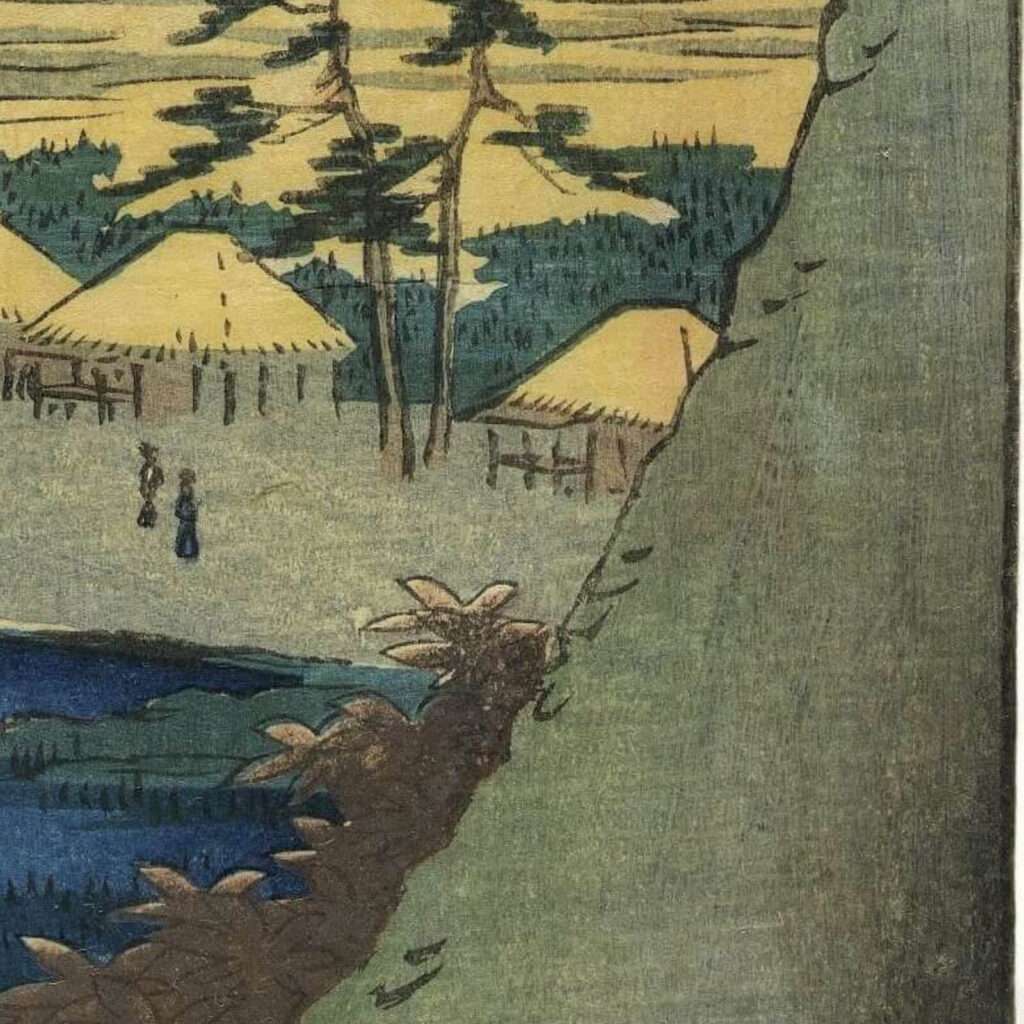

Utagawa Hiroshige typically created a disruptive sense of depth with objects immediately placed by the viewer. This print is no exception. Framing the foreground are the split trunks of a tree. It is most likely an Acer palmatum more commonly known as Japanese maple. Its two trunks flank the left and right sides of the print with more delicate branches bridging across the middle with many leaves filling the foreground.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

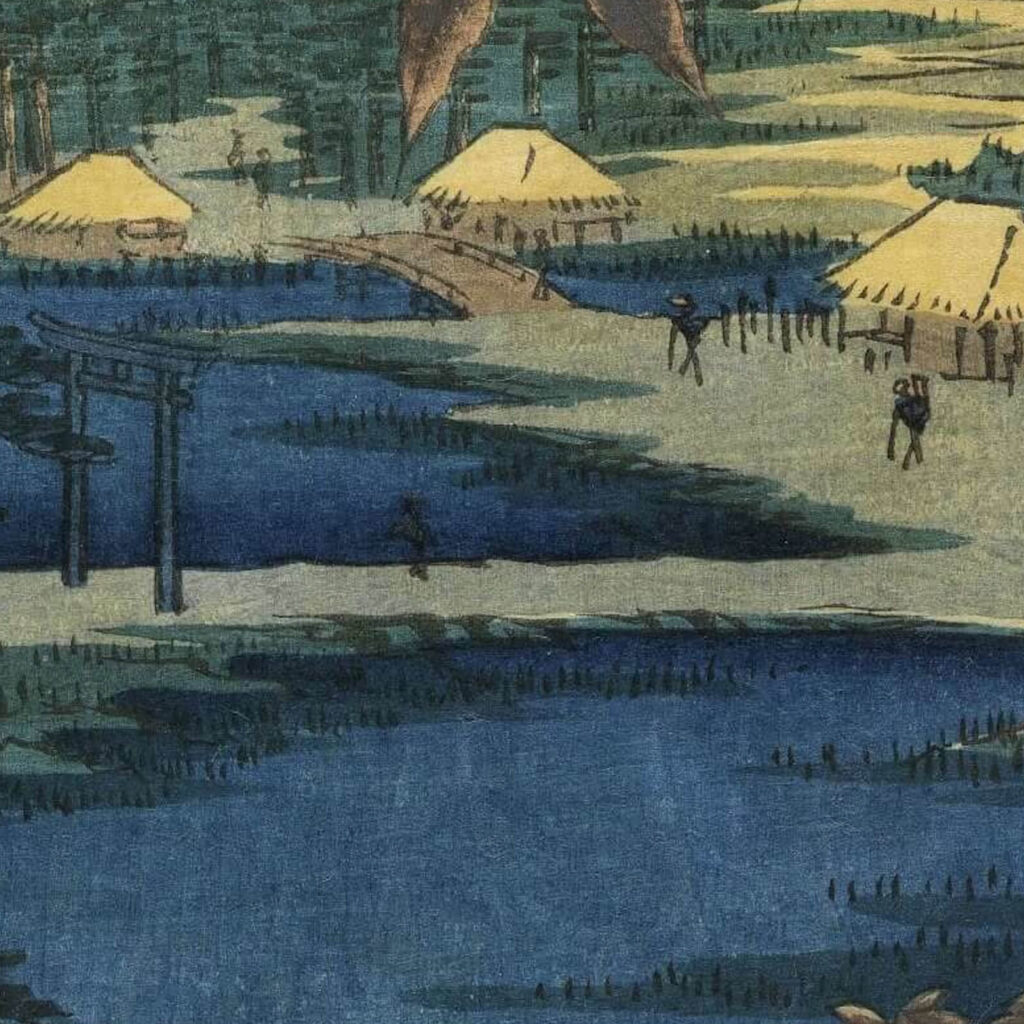

Viewed through the Japanese maple is a midground filled with people, buildings, fields, and lakes. On the midground’s left side is the Tekona Shrine. It is connected to the lake’s right side by a land bridge. This bridge bisects the waters of the midground. What is indecipherable is whether the Tekona Shrine is on a small island in the middle of the lake or simply on the left bank of the lake. The framing of Japanese maple hides the temple’s left side and surroundings.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Seven people walk around in the midground. One is crossing the land bridge and appears to be approaching the Tekona Shrine. Two individual men with walking sticks are walking deeper into the midground as they approach the wooden Tsugi Bridge. Two figures are on the other side of the bridge and are emerging from the forest. Closer to the viewer, two clustered women walk toward the foreground away from the Tsugi Bridge. All the figures are in movement. No one is standing still. There is a sense of capturing a fleeting moment. In several minutes all these figures will disappear as they move beyond the framed edges of the picture plane.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge is an example of fūkeiga or landscape. It continues its depth by the green forest stretching towards the base of distant mountains. The gray mountains straddle the horizon and add a definite edge to the scene. What is beyond the mountains is unknown. However, they anchor the scene as a solid background. Solid monumental mountains compared to the delicate diminutive village.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Fūkeiga first became important in 19th-century Japan due to two commercial factors. The first was the improvement of travel within Japan. Trains began to emerge in the late 19th century, which facilitated the movement of domestic tourists. Domestic tourism boomed and travelers wanted keepsakes of their travel destinations. The landscape prints became the perfect items.

The second important factor was the introduction of Prussian blue paint into the Japanese art market. It was created in Germany in the early 18th century and became the first modern synthetic pigment. It was far more affordable than lapis lazuli-based paints. By the early 19th century, it was imported by Japanese printmakers like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige to create Japanese masterpieces like Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa and Hiroshige’s Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge that use extensive Prussian blue for their seas, lakes, and skies.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Utagawa Hiroshige, like many of his Japanese contemporaries, was influenced by eastern Asian art, especially Chinese. Despite the Tokugawa shogunate’s isolationist policies, there were still foreign elements borrowed and included in Japanese artwork. The influence of Buddhism can be seen in exploring the temporal changeability of locations. This, and many other prints, explore the different light conditions caused by seasons and weather. Like French Impressionists on the other side of the world, Japanese artists were observing their world not as a constant experience but as an inconstant event.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

The Edo Period ended in 1867, and the years leading to its demise was marked by turmoil and instability. Feudalism was ending, and modern Japan was beginning. Industrialization was spreading across Japan bringing an end to feudal society. Did Utagawa Hiroshige have a growing sense of nostalgia for pre-industrialized Japan? Did he try to capture a vanishing world through his prints? Hiroshige certainly captured many landscapes now lost to modern Japan. However, the essence of their beauty is still iconically Japanese. It can still be found in the more remote regions. Political regimes may rise and fall, but the beauty of the Japanese landscape is persistent.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1857, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

“Fūkeiga.” Van Gogh Museum. Accessed 22 January 2022.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

“Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugi Bridge”, Collection, Van Gogh Museum. Accessed 22 January 2022.

“Ukiyo-e”, Subjects, Van Gogh Museum. Accessed 22 January 2022.

“Utagawa Hiroshige”, Van Gogh Museum. Accessed 22 January 2022.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!