12 Best Shots of the World Press Photo 2024 Exhibition

The World Press Photo Exhibition is a renowned annual event showcasing some of the most impactful visual photojournalism from across the globe.

Nikolina Konjevod 10 February 2025

Is seeing believing? In 19th-century London, this question captivated everyone who entered Frederick Hudson’s spirit photography studio—from scientists to supernaturalists and everyone in between.

In 1874, the scientist Alfred Russel Wallace visited the London photography studio of Frederick Hudson. He was there to commission a new, uncanny kind of portrait that was taking Victorian era England by storm: spirit photography. It was a controversial and short-lived phenomenon, but a phenomenon nonetheless. It transformed Wallace’s understanding of science and the material world, and he was far from alone.

Spirit photography emerged during the American Civil War, a time when new technologies and untimely deaths were both pars for the course. At the same time, a burgeoning theological movement called Spiritualism was spreading across America and Great Britain. Spiritualists believed that unseen spirits existed in the material world and that it was possible to communicate with them. This unique cultural climate catalyzed the rise of spirit photography across the pond. Frederick Hudson is credited as Britain’s first spirit photographer.

Frederick Hudson, Album of Spirit Photographs, 1872, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Museum’s website.

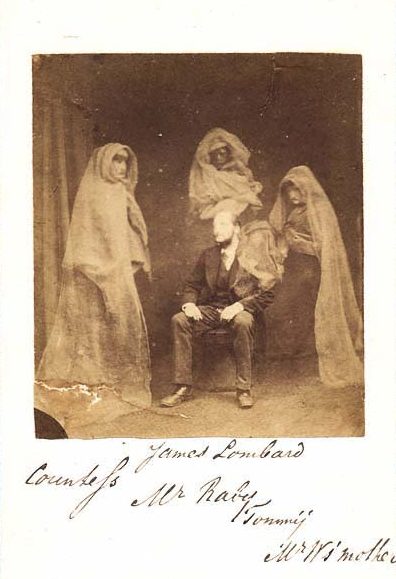

At his soon-to-be-infamous Kensington studio, Frederick Hudson introduced Londoners to spirit photography in 1872. He created commercial portrait photographs wherein specters appeared alongside the flesh-and-bone sitter. These spirits were typically translucent with ambiguous facial features and white drapery.

The resulting portrait usually revealed a ghostly friend or family member—invisible to the naked eye but detectable through the photographic process. Sometimes a famous figure like Abraham Lincoln or Beethoven mysteriously appeared in the image.

Was it a modern miracle or technological trickery? Hudson’s spirit photographs attracted many satisfied customers, especially those with deceased loved ones. But he also faced vitriol from skeptics, who accused Hudson of secretly using double exposures and other tricks to defraud believers.

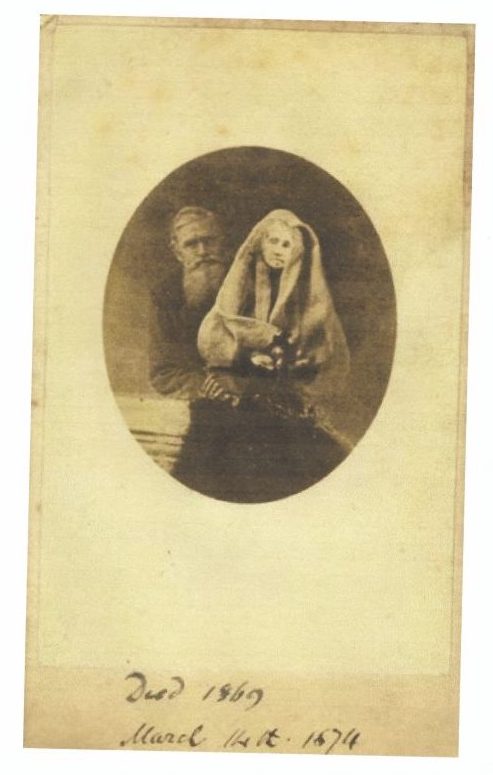

Frederick Hudson, Alfred Russel Wallace with the spirit of his mother, 1874. The Media of Mediumship.

One of Frederick Hudson’s most famous clients was the aforementioned Alfred Russel Wallace. A well-respected scientist, Wallace developed theories of evolution with Charles Darwin and pioneered the discipline of biogeography.

After sitting for an 1874 spirit photograph, Wallace entered the public debate in defense of Hudson. Wallace had been photographed alongside the spirit of his recently-deceased mother (pictured above). Her likeness, Wallace claimed in a widely-circulated essay, was irrefutable and could not have been forged.

It wasn’t unheard of for a scientist like Wallace to espouse seemingly supernatural beliefs. Spiritual and scientific ideas were not considered mutually exclusive in Victorian-era discourse. After all, if a microscope could bring previously invisible microorganisms into the visible world, who was to say that photography couldn’t prove the existence of spirits?

Frederick Hudson, Georgiana Houghton with Tommy Guppy and spirit, 1872, Collection of The College of Psychic Studies, London, UK.

What does it mean to see? And what does it mean to believe? Are these notions interrelated, interchangeable? In addition to new tools like microscopes, telescopes, and even kaleidoscopes, the invention of photography dramatically expanded the scope of what could be seen—and believed—in the 19th century.

Scientific discovery has always inspired as many questions as it does answers. For Victorian-era purveyors of spirit photography, such questions represented a thrilling new frontier to be explored, both scientifically and spiritually. Today, as photography grows more advanced and more accessible by the day, people grapple more than ever with the question of whether seeing is really believing.

Frederick Hudson, Mr. Ruby with the Spirits “Countess”, “James Lombard”, “Tommy”, and the Spirit of Mr. Wootton’s Mother, c. 1875. The American Museum of Photography.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!