Summary

- Anatomical art uses traditional forms of art or new technologies to describe the body.

- Anatomical illustration is important to teaching and study of anatomy. Leonardo da Vinci and other artists used it to make their art as realistic as possible.

- Anatomical wax modeling started in the late 17th century and produced sculptures unsettling in their vividness.

- Wax models helped to end the horrific trade of dead bodies in London.

- Preserved body parts, as well as their replicas, were used from Ancient Egypt through Christian culture to the present day. Richly decorated reliquaries objects constituted a major form of artistic production in the Middle Ages.

- Torajan people of Indonesia have been mummifying the whole bodies of the deceased and keeping them at home or in tombs.

- Contemporary artists use various practices regarding the body. Orlan uses body as a canvas. Marina Abramović explores the endurance and limits of the human body through performance art. Marc Quinn uses body elements (like blood) in his art.

- Ten of the best contemporary sculptural artists who work with the human body.

Fascinating Organisms

Anatomy and art have always been inextricably linked, and is that any surprise? Aren’t we all utterly fascinated by the form, structure, and habits of our human bodies? Pure anatomy is the structural science of living organisms. When we add art into the mix, we find the creative expression of the very essence of life. Anatomical art describes the body – skin, bones, muscles, and organs. That might be sketches, paintings, or sculptural forms. More recently, it includes photography and new technology such as cybernetics, thermal imaging, and body scanning.

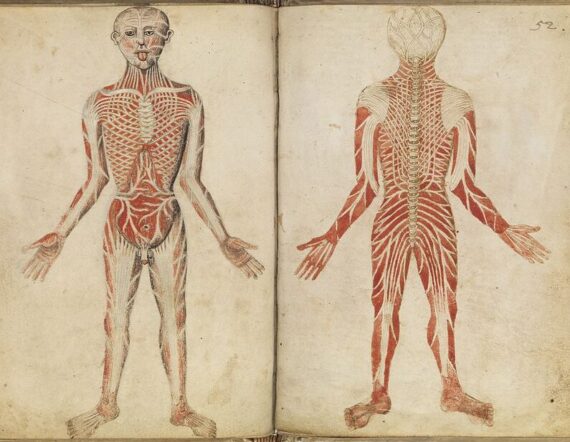

Claudius Galen, Muscles Man, c. 131-201, Wellcome Foundation, London, UK.

Teaching Tools

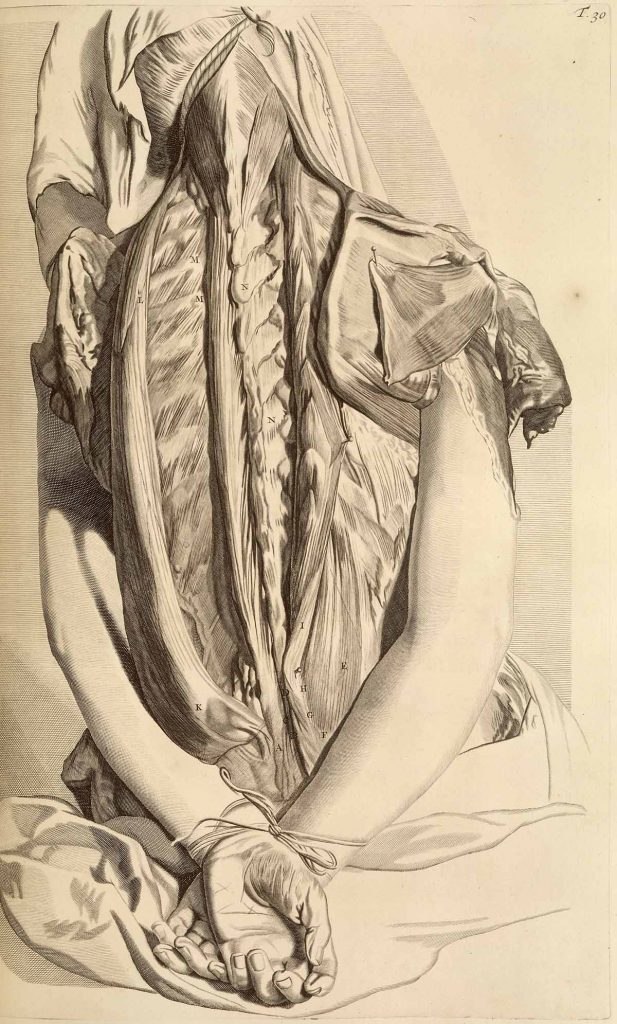

Anatomical illustration is fundamentally important to the teaching and study of anatomy. DailyArt writer Camilla De Laurentis has written a definitive guide to this. The influential anatomical studies of the Greek-born physician Galen (129–216 CE) dominated European medicine for hundreds of years. Andreas Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy. He worked with an artist and an engraver to transform his human dissections into beautifully detailed and annotated images. In 17th-century Amsterdam, artist Gerard de Lairesse (a pupil of Rembrandt), worked closely with surgeon Govard Bidloo to produce some of the most intricate and arresting anatomical studies of the body. There is a realism, compassion, and even sensuality to these drawings, which are considered masterpieces of the Dutch still life period.

Bidloo and Lairesse, anatomical illustration, 1690, National Library of Medicine, London, UK.

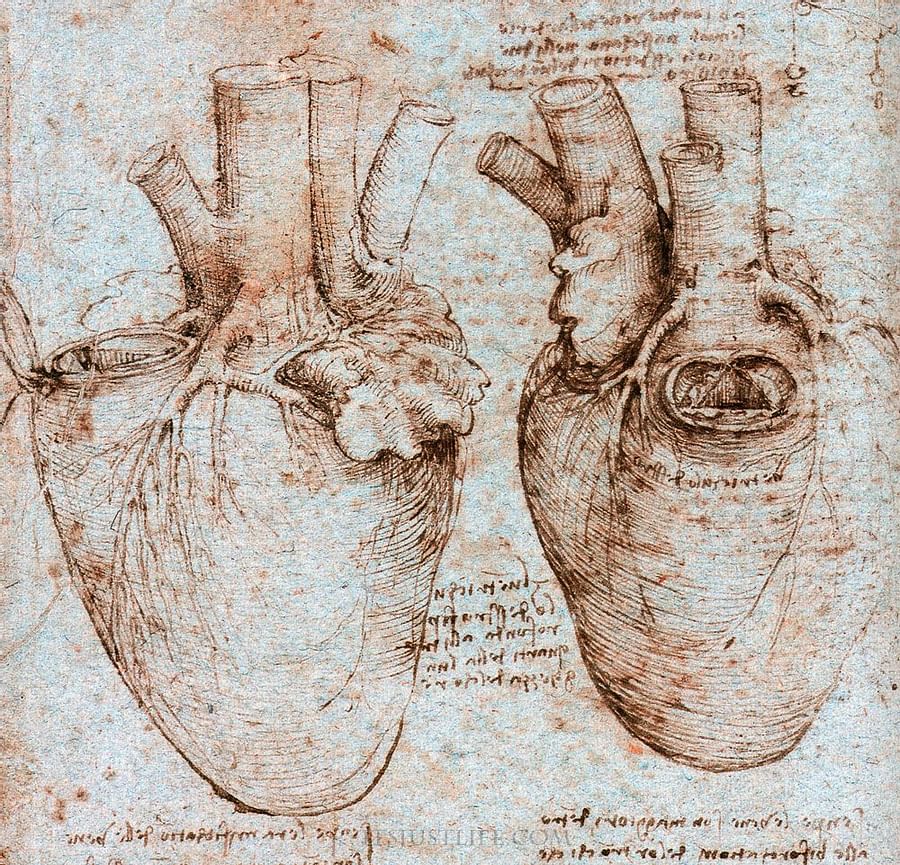

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci is perhaps the best known anatomical illustrator. Da Vinci carried out his own dissections on over 100 human corpses, producing numerous drawings and sketches based on these investigations. It could be said that all artists during the Renaissance were anatomists – to produce such incredibly lifelike and realistic portrayals, they needed a deep and thorough understanding of how the body worked under the skin. However, of all of the Renaissance painters, Leonardo da Vinci is, without doubt, the most significant and prolific, inventing a new vocabulary for scientific anatomical illustration.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Heart and Its Blood Vessels, c. 1510, Stanford University, California, USA.

Wax Modelling

Full body anatomical wax modeling started late in the 17th century in Italy. A major step from two-dimensional anatomical illustrations, this was the body translated into three life-sized dimensions. Wax can be moulded, colored, tinted, layered, and can even be set with hair, teeth, and nails to create a version of the body which is unsettling in its vividness.

Perhaps the most famous wax model was made for (and still resides at) La Specola Museum in Florence by Italian sculptor Clemente Susini. It is called the Anatomica Venus, or the Medici Venus. This highly realistic, life-size wax model of a naked woman could be dissected in seven layers, ending with a tiny fetus curled up inside her womb. What makes this more artistic (or weirder?) is that she has a full head of real human hair and she wears a string of pearls around her neck. Her head is tilted back on a soft cushion, with an ecstatic expression on her face. Bear in mind that back then a look of ecstasy was sacred, not erotic. The same expression would be found in many religious paintings – it evokes mystery, not sex.

Clemente Susini, Anatomical Venus, 1780, Morbid Anatomy Museum, New York, NY, USA.

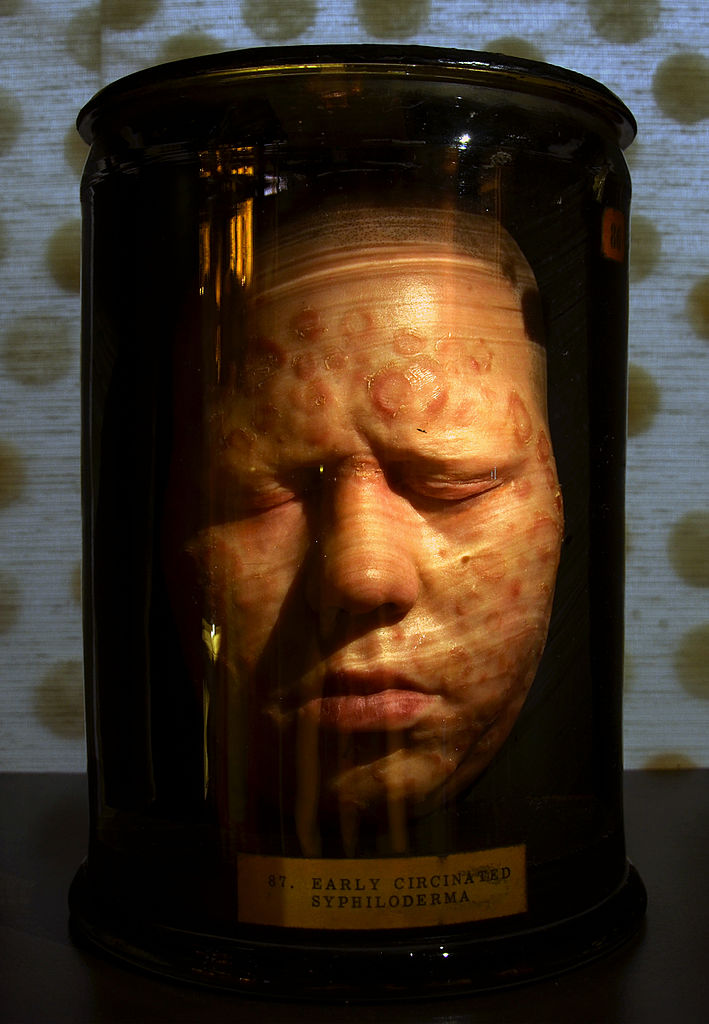

Grave-Robbers

There is a stark contrast between these extraordinary early Italian models and the style of the London-based sculptor Joseph Towne. He produced moulage pieces (mock injuries on wax figures for training purposes) for students at St Guy’s Hospital, London. In his career, he produced over 1,000 anatomical models, some of which are still held at the Gordon Museum at King’s College London. The use of these models helped contribute to the end of the horrific trade in dead bodies for dissection. Criminals and paupers who died in the workhouse were handed over to medical schools, but this did not provide enough cadavers. So grave-robbers, or ‘resurrection men’ as they were more euphemistically called, illegally dug up bodies to deliver to medical schools. Edinburgh-based Burke and Hare have been immortalized in stories and on film. In 1827, they resorted to multiple murders in order to satisfy the demand for bodies.

Joseph Towne, wax head with syphilis, 1840, Museum of London, London, UK.

Votives

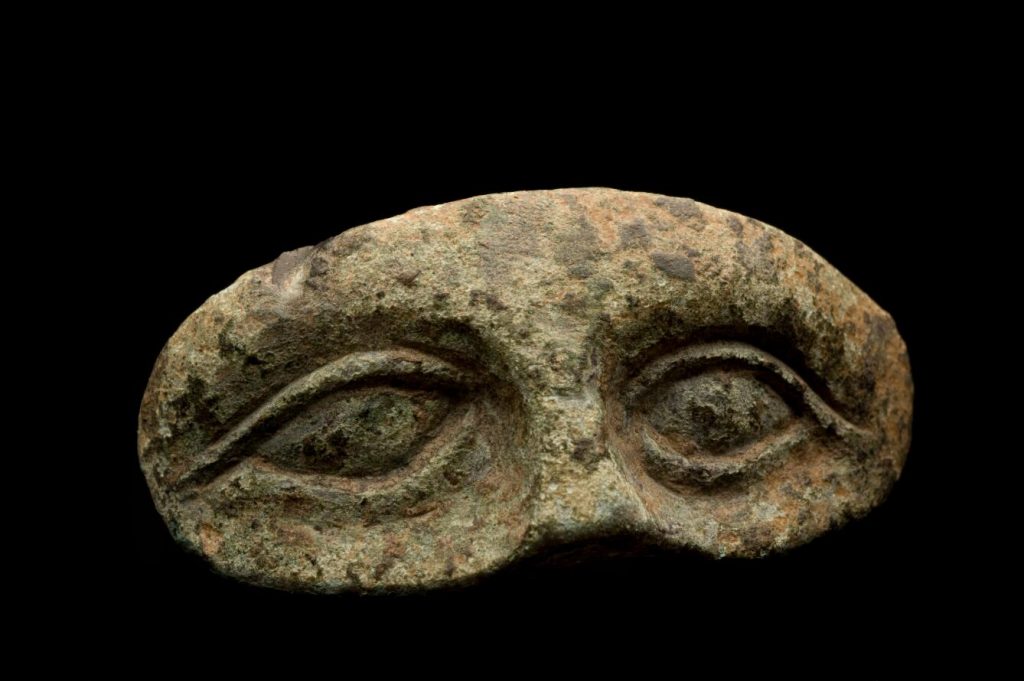

Votives have played a role in human cultural life from pre-Christian times to the present day. Early examples were made of terracotta, some were made of marble or even bronze. Later they were made of wax, and today may be made of plastic. The offering of objects to a pagan god, or a divinity, or to a Christian saint, to ask for a grace, or to give thanks for a received grace, is a very ancient custom. People place objects at shrines, in churches, or at places of pilgrimage. Some of these objects are incredibly well-made and rather beautiful. DailyArt Magazine writer Marga Patterson explores them in more detail here.

Roman votive eyes, c. 200BCE-100 CE, Science Museum and Wellcome Collection, London, UK.

Ancient Cultural Relics

We know quite a lot about how ancient civilizations preserved body parts. Our enthusiasm for Egyptian mummies shows no sign of waning. Cultural practices that revere the dead treat the body as a container for the soul, not just a sack of skin and bones – body parts have totemic value. Ancient texts describe ritual practices of the Celts during the Iron Age. They removed the heads of enemies killed in battle and embalmed them for display in front of the victors’ homes. Oil from cedar or pine cones was used for the embalming process. People from the earlier Bronze Age would introduce ancestors’ remains into their buildings, as a protective totem or purely in remembrance.

Annie Cattrell, Capacity, 2001, The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum, Scotland. Pinterest.

Bones of the Saints

The bones of saints have made for brisk trade from antiquity. DailyArt Magazine writer Marta Bryll has explored some of the most fascinating examples. People made pilgrimages to visit relics, which were believed to heal the sick or even cure the plague. Less valuable (third class) relics can still be bought and sold today. Artisans designed richly decorated caskets, called reliquaries, to hold and display these bones. These objects constituted a major form of artistic production across Europe and the Byzantine Empire throughout the Middle Ages. Paintings explaining the story of a relic were also another major feature of artistic production in this period.

Saint Balbina reliquary bust, c. 1520-1530, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Animist Beliefs

Taking a step on from small relics, in a mountainous area of Indonesia, the Torajan people mummify the whole bodies of the deceased. Keeping and caring for these preserved bodies for years is a tradition dating back centuries. Their animist beliefs blur the line between life and death, making the dead very much present in the world of the living. Historically stuffed with leaves and herbs, formalin (a preserving chemical) is used now. Torajans are rarely buried in the ground. If not at home, they are placed in tombs, caves, or even in a hole carved out of a tree, so that the body can be easily accessed. In their absence, a wooden figure may be carved. Known as tau tau, these sculptures wear the clothes, jewelry, and even the hair of the deceased.

Spike Blackhurst, Mind Control, 2021. Artist’s website.

Body as Canvas

It could be said that the earliest known evidence of ‘artistic behavior’ is humans decorating their bodies. Our earliest ancestors were as fascinated with their bodies as we are. Decoration or sacred markings might include piercing, tattooing, and dyeing patterns into the skin with ochre and the addition of beads, bones, and shells. There are artists today who follow this rich tradition of using the body itself as the canvas or as the source material. Provocative French artist Orlan uses her body to explore and question social norms. Her most controversial works have involved prosthetics and surgical interventions, reconfiguring her own flesh, whilst conscious, reciting poetry. In the early 1990s, she had two bumps or ‘horns’ implanted above her eyebrows. More recently, she got celebrity news feeds buzzing when she sued Lady Gaga for ‘copying’ her imagery and innovations. Orlan didn’t win her plagiarism case, but she certainly made the headlines.

Orlan, La Liberte En Ecorche, 2013, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland.

Body as Performance

Some use the whole body in performance art. Calling herself the ‘grandmother’ of performance art, Serbian Marina Abramovic explores the endurance and limits of the human body in sometimes distressing and often exhausting conceptual art. For Abramovic, the aim is nothing less than transformation for both audience and artist. She had long-term collaborations with German artist, Ulay. In her 50-year career, she has set herself on fire, carved her skin with a knife, and taken dangerous doses of controlled drugs before an audience. She has recently published a box set of instructions cards, containing exercises to reach an altered state and reach creative potential. Musicians Jay Z and Lady Gaga are both enthusiastic converts to the “Marina Abramovic Method.”

Marina Abramović, Miracle 4, 2018. Art Basel.

Body as Horror

Wonder, exploration, and respect for the human body is what we are exploring here – not flayed skin, dismembered bodies, and gore. But if horror IS your thing, check out the (in my very personal opinion) vastly over-rated Damien Hirst‘s Virgin (exposed) or Hymn. Or look at the plastinated bodies of German anatomist Gunther von Hagens in his Body Worlds exhibitions. Kittiwat Unarrom creates gruesomely authentic dismembered body parts. The intriguing part of his horror show is that he makes everything out of bread in his family bakery.

Anne Mondro, Breathe, 2009. MedinArt.

Bloody Portraits

Before we move on, we should probably mention one of the most famous pieces of body art. Marc Quinn follows a long art historical tradition of the self-portrait. But he veers firmly away from tradition by making his sculptures from 10 pints (5.7 liters) of his own frozen blood. The stainless steel plinth for the head is a refrigeration unit, hinting at futuristic ideas of cryogenics or suspended animation. Quinn committed to produce one of these heads every five years. He calls them ‘sculptures on life support’ as they rely on technology and a complicated infrastructure to survive. A flick of a switch and that head could be nothing but a bloody puddle. His other sculpting materials have included DNA, feces, and the placenta from the birth of his son.

Marc Quinn, Self, 2006, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK.

Ten of the Best

Now, let’s take a look at some of the finest sculptural artists working in anatomical art today. To make the list, each of these artists had to be making cutting-edge, breath-taking art, and also be involved in the crafting and fabrication processes, where emotional and practical exploration are entwined. No ‘artist factories’ here, where the artist sets their assistant minions to work and adds their name at the end! Here are 10 of the best artists working across the globe today, exploring the human condition through the body. And all of them are women. Prepare to be wowed!

Spike Blackhurst, Love, 2021. Artist’s website.

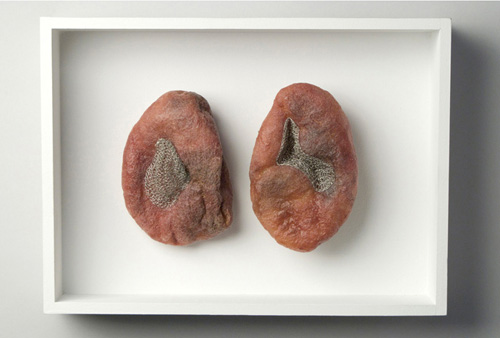

1. Spike Blackhurst

Trained in fine art, sculpture, and blacksmithing, pioneering artist Spike Blackhurst produces work exploring the tension between fragility and strength, whilst adding to the political discourse on emotional abuse and trauma. This Wales-based sculptor says she is a process artist, pushing the boundaries of what is possible. Her sculptures focus on bodily organs, what they represent to us, and how they hold the trauma of emotional abuse. However, Blackhurst is not just creating art but also designing her own tools and processes to fuse metal and ceramics. She mixes cutting-edge technology and ancient practices like Raku to create astonishing works.

Spike Blackhurst, Anxiety, 2021. Artist’s website.

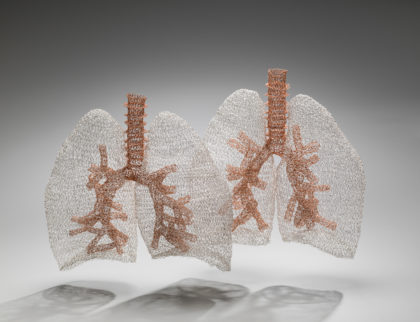

2. Anne Mondro

This American artist was fascinated by anatomical specimens even as a child. She explores the physical and emotional complexity of the human body through traditional crafts, fine art, and digital technology. She creates images and sculptures from crocheted wire, copper, silver, wool, and wax that investigate our humanity. Mondro spends hundreds of hours on each piece and has exhibited across the world.

Anne Mondro, of all the souls that stand create, 2014. MedinArt.

3. Karine Jollet

Using soft and flexible fabric to evoke body tissues, Jollet finds the human body utterly beautiful. Every work is white, and for Jollet, this allows a connection and flow between all the works, reminding us of unity and purity. This French artist specifically refers back to the beliefs our ancestors had about the body and spirit, and the tradition of votives. She says she doesn’t find anatomy at all morbid but instead sees wonder and beauty.

Karine Jollet, Heart Arborescence, 2011. MedinArt.

4. Kate MacDowell

Although her works are clearly part of an art history tradition, they are also MacDowell’s response to the world we currently inhabit where climate change and toxic pollution threaten our very existence. American MacDowell hand sculpts each piece out of porcelain, which has the unique ability to be both beautifully fragile and yet can last thousands of years. On her website, she says that she sees each work as a captured and preserved specimen, a painstaking record of endangered natural forms, and a commentary on our own culpability.

Kate MacDowell, Venus, 2006. Artist’s website.

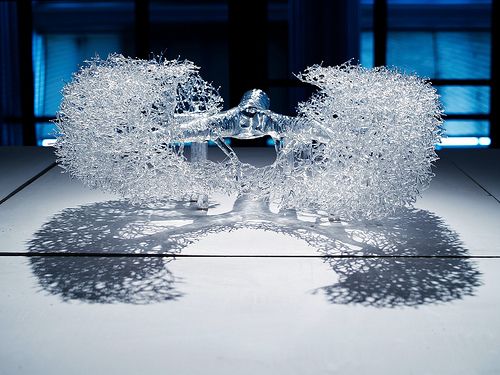

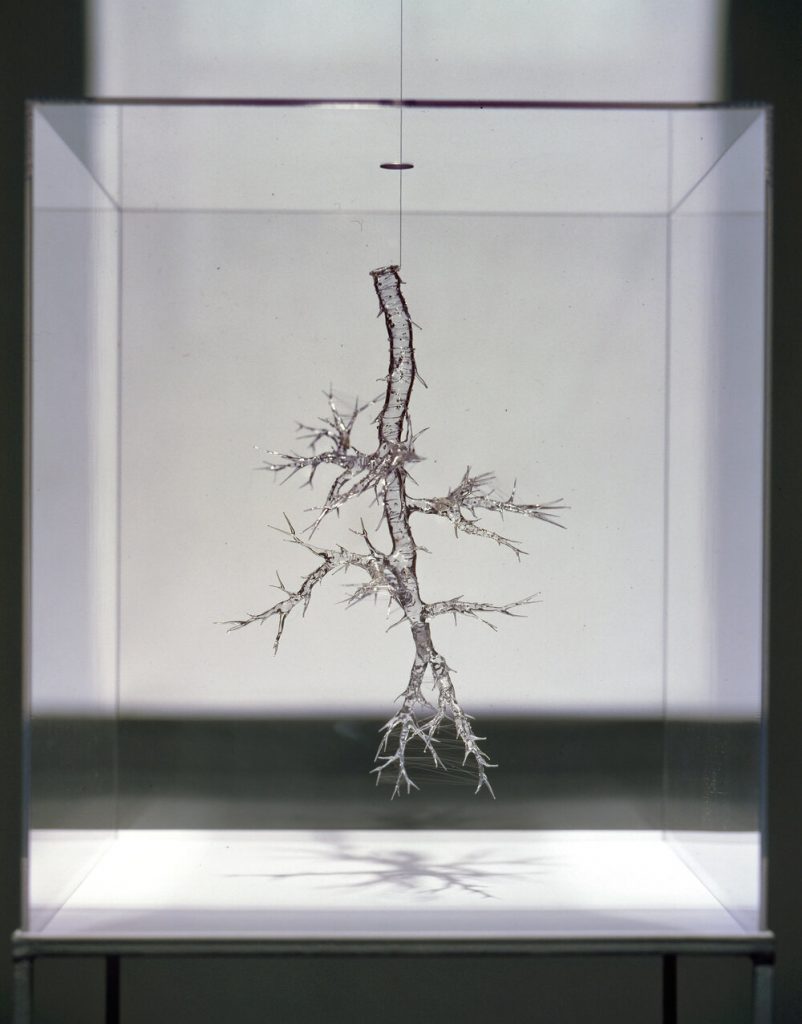

5. Christine Borland

Borland crafted a work called Bullet Proof Breath in 2001, showing the tiny airways of the lungs. Unbelievably, she made it with spider silk and glass. Here we see both fragility and strength, a mixing of natural resources and technology. Much of Borland’s work explores deterioration versus regeneration, and she works closely with colleagues in medicine.

Christine Borland, Bullet Proof Breath, 2001. Artist’s website.

6. Debra Baxter

Baxter works with carved alabaster, glass, bronze, wood, and metal. She combines them with natural forms like crystals and minerals. She produces sculptures that explore the line between life and death, loss and legacy. Trained in sculpture and jewelry design, she spent time studying in Italy and lives in the American South West. Her work ranges from museum pieces to ready-to-wear jewelry.

Debra Baxter, Catch Your Breath, 2021, Form and Concept Gallery, Santa Fe, CA, USA.

7. Annie Cattrell

During her studies at the Glasgow School of Art, Cattrell spent quite a lot of time in the Museum of Anatomy, usually reserved for medical students. Her fascination with the topography of the body and the art/science connection has never waned. Cattrell’s practice is often informed by working with specialists in neuroscience, meteorology, engineering, psychiatry, and the history of science. This cross-disciplinary approach results in astonishing and elegant works.

Annie Cattrell, Process, 2006, Dublin Science Gallery, Dublin, Ireland.

8. Chantel Pollier

Originally trained as a psychotherapist, Pollier worked with children with learning disabilities and socio-emotional problems. She later graduated in sculpture, specializing in stone sculpture techniques and moulage techniques. The physical world and its inevitable decay is her theme – the fragile body, ephemeral and temporary. Pollier works mainly in marble and alabaster, adding in wax and glass to the process. Drawings and paintings precede her three dimensional works and, sometimes, these become works on their own.

Chantal Pollier, The Heart of the Matter, 2009-2011. Artist’s website.

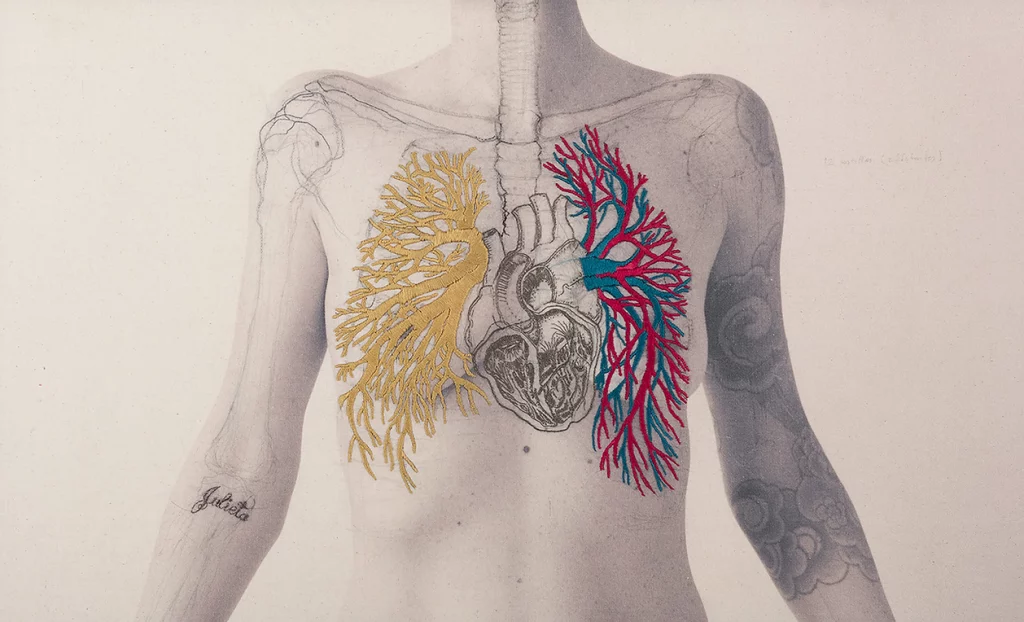

9. Juana Gomez

This Chilean artist uses fabric and thread to explore the systems that control the human body. Her images of the circulatory, endocrine, and nervous systems hark back to those early anatomical illustrations we explored earlier. Gomez looks for patterns and networks in the human that resemble trees or river systems in nature. She looks at the microcosmos and the macro cosmos, the interior and the exterior, looking for a common language.

Juana Gomez, Constructal 3, 2006. Artist’s website.

10. Mona Hatoum

Palestinian artist Hatoum was raised in Beirut, Lebanon, but during a visit to London in 1975, the Lebanese civil war broke out and Hatoum was forced into exile. She explores the parameters of the body, but also the political and geographical sense of dislocation experienced through exile. In Rubber Mat, human guts spill out onto the floor. The silicone rubber intestine has a sheen and texture that is both inviting and disturbing. Visitors can touch, poke, or even lay upon the surface.

Mona Hatoum, Rubber Mat, 1996, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA, USA.

Scientific and Personal Truth

All of these artworks display a truly multi-disciplinary way of working in art, combining aesthetics, artistic expression, technological skill, scientific truth, and personal truth. These artists engage us because we all have bodies, and we find ourselves fascinating and scary, wonderful and repulsive, all at the same time. The relationship between the visual arts and anatomy is rich and diverse – an obsession amongst artists that thankfully shows no sign of declining. Have I missed anyone essential from this list? Add your comments to our thread!