Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

Vincent van Gogh’s career lasted only about 10 years. Yet, during that time, he painted some 36 self-portraits. Only Rembrandt painted more, with 80 known self-portraits, and Rembrandt’s career lasted about 4 times that of van Gogh! Have you ever wondered what was Vincent’s first portrait? The answer reveals as much about Vincent the man as it does about his art.

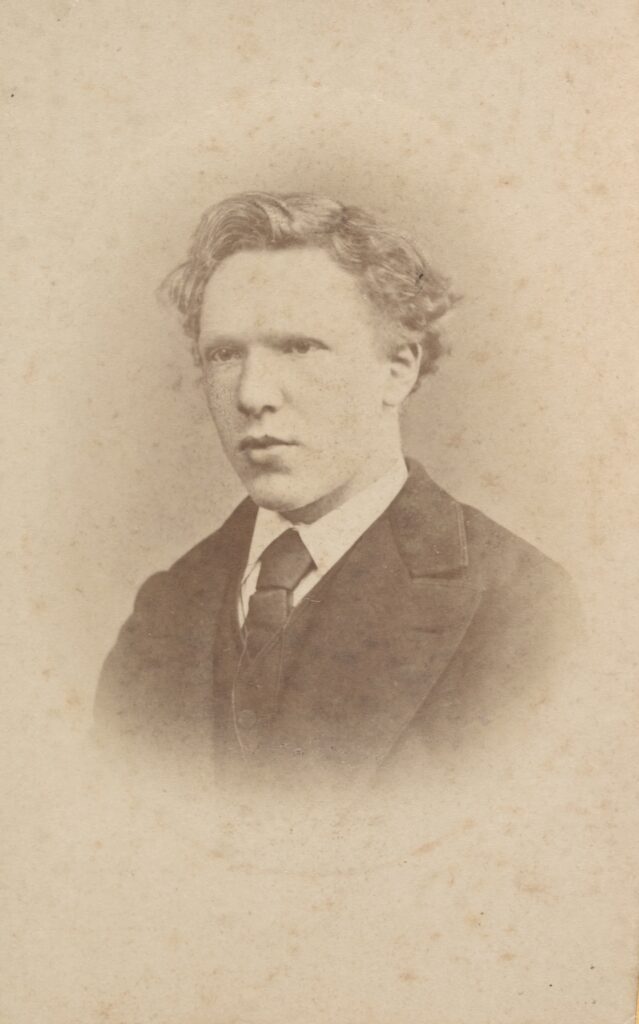

Only known photographic portrait of Vincent Van Gogh at 19, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

With only one surviving photograph, Van Gogh’s portraits provide so many clues about this intriguing artist. Through the portraits, we can tell what Van Gogh looked like (with and without the beard!), hair, and eye color that we could not tell from the photograph. We can tell what kind of clothes he wore, his moods, even some of the art he admired, as is the case of the Self-Portrait with a Japanese Print. We can even trace his mental state and the evolution of his artistic career, all providing a fascinating look at Vincent van Gogh—the human.

But, perhaps you are wondering—why so many self-portraits?

People say – and I’m quite willing to believe it – that it’s difficult to know oneself – but it’s not easy to paint oneself either.

Vincent Van Gogh, Letter (#800) to Theo van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Thursday, 5 and Friday, 6 September 1889

Vincent van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Van Gogh’s life was plagued by a chronic lack of funds. One of the things that make his personality so incredibly fascinating is that he seems to completely have transcended the material. From his correspondence, we don’t get the sense that he wanted money for money’s sake, as that he needed it to further his work. In this respect, his younger brother, Theo, supplied Vincent with emotional and material support, as well as the confidence he needed that his work was valuable in the face of rejection.

During the two years he spent in Nuenen, Vincent painted some 40 head studies of different people he met there. All the hard work paid off in The Potato Eaters. However, the practice was not easy to come by. He wrote to Theo,

While I’ll also have to pay out again next month. I can or may not do anything other than spend a relatively large sum on models. It’s the same here as everywhere else; people are far from happy to pose and, if it weren’t for the money, no one would… But to make what I want and, above all, get the figures better, is really a question of money… But don’t take it amiss of me when I say that if Serret and you—and in my view very rightly want to see other things in my figures—I’ll have to spend rather more on my models.

Vincent van Gogh, Letter (#513) to Theo van Gogh, Nuenen, on or about Sunday, 12 July 1885

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Peasant Woman with White Cap, 1884, private collection.

There was an earnestness in Vincent’s personality that expressed his inner world by looking outward. His desire to help humanity led him to become a teacher, preacher, and even a missionary, all without success, before he found his calling in art. Perhaps it was only a matter of time before he would gravitate to painting people to tell his own story.

Vincent wrote to Theo, as he worked from Nuenen,

Now look here—to make progress, because I’m just getting into my stride, I have to paint 50 heads. As soon as possible and one after the other…

Vincent van Gogh, Letter (#468) from Nuenen, on or about Sunday, 2 November 1884

Eventually, the move to painting self-portraits was not so much a matter of self-expression as it was a matter of economy. The one model who was always with him and would not charge him extra was himself.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Vincent van Gogh was so poor that he could not pay his rent anymore, so he made a move to Paris in early 1886 to be with his brother. What may be his first self-portrait comes right after his arrival there. The piece is an oil on canvas, only 27.2 x 19 cm (about 10.7 x 7.4 inches). Experts believe he worked on it sometime between March and June, and in a single session.

Looking at it now, it does not resemble at all the later self-portraits that Vincent would be known for. His attitude as a sitter, his demeanor, and the way he is posing, are a far cry from the iconic Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat. Even though the pigments have faded over time and the work was, overall, a little brighter, here he is still using the somber color palette he had been using in Nuenen and Antwerp.

His technique is very reminiscent of the work he did for The Potato Eaters, the portraits from Antwerp, and all the still-lifes in between.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1886, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Even now, it is fantastic to see the brush strokes, most noticeable on the forehead and hairline—the bright focus of this piece—and also defining the outline of Vincent’s coat, tie, and pipe.

For Van Gogh things were just about to change…

This self-portrait almost marks the end of an era for Vincent. After moving to Paris and having his eyes opened to a whole new cosmopolitan world, one of Vincent’s first influences came in the form of Adolphe Monticelli.

Adolphe Monticelli, Portrait de l‘artiste, 1866, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Monticelli was born in Marseille, in the south of France, where the days are sunny and long, and there is color everywhere. He was classically trained under Paul Delaroche, and his favorite artists were Rococo painter Jean-Antoine Watteau and Romantic Eugène Delacroix. But, Monticelli took all these influences—from Rococo to Romanticism to Realism—and put them toward something new.

Adolphe Monticelli, Vase of Flowers, 1875, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

His interests did not lean toward the realistic form of things, but rather to their essence and color. He made liberal use of a technique called impasto, in which the artist lays paint on the canvas very thickly so that, when the paint dries, the brushstrokes are textural and highly visible. Does this not remind you of van Gogh’s later work?

The Van Gogh brothers greatly admired this style so full of life, emotion and color. Theo used his influence at his art gallery to begin collecting Monticelli’s paintings. They even helped publish the first book about him.

Jo van Gogh-Bonger, Anna van Gogh-Carbentus (Vincent van Gogh’s mother) and Vincent Willem van Gogh in the Hague, Netherlands. 1903. Photograph by Onbekend via The Memory.

This little self-portrait of Vincent’s was left at Theo’s apartment sometime between March and June 1886. After Theo’s death in 1891, his widow Jo van Gogh-Bonger and their son Vincent Willem inherited it, along with some other 400 paintings of Vincent’s. In its long history, this special painting has been entrusted to both the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum (which hosted the first large exhibition of Vincent’s work). It is currently on view at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh was one of these people who come fleetingly to the world and change things. Even though the self-portraits may have been born out of necessity and practicality, Van Gogh’s willingness to look at himself truthfully and present himself just as he was inspires us, today, to do the same.

Vincent van Gogh, The Letters, ed. Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker, 2021, vangoghletters.org. Accessed: 29 Jul 2024.

Rainer Metzger, et al., Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Paintings, Taschen, 2015.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!