Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Vinnie Ream became the first woman to win a US government commission for a statue in 1866—at the age of 18! She created a life-sized figure of President Abraham Lincoln, gazing down at the Emancipation Proclamation he holds in his right hand. Ream and her marble statue caused a huge scandal that raged in Washington, D.C., and across the nation.

The public questioned how this petite, attractive teenager with little artistic training won this coveted opportunity. Senators accused her of seducing congressmen and Civil War generals. Some objected to her sympathetic portrayal of the recently assassinated president. Others criticized her method of creating the marble statue. Like many women artists, she faced many hurdles. Here is the story behind her marble statue of Lincoln that still stands in the US Capitol.

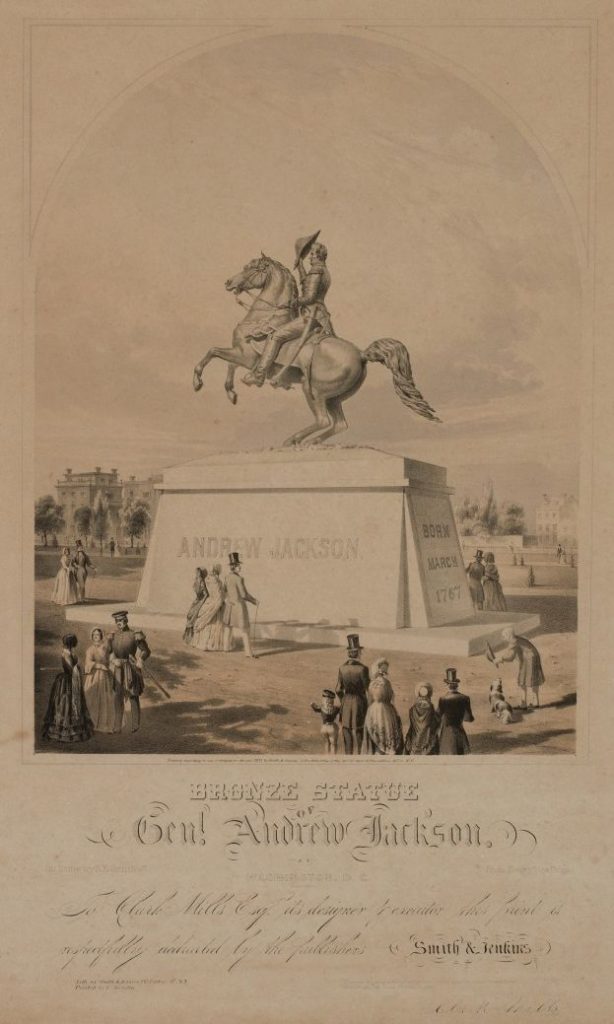

At only 14 years of age, Vinnie Ream moved with her family to Washington, D.C. in 1861. She found a job in the Post Office on 8th & F. Street N.W. (now the Hotel Monaco) and volunteered in the evenings for the Sanitary Commission (now the American Red Cross). In 1864 James S. Rollins, the representative for the Reams’ home state of Missouri, took Ream to the studio of Clark Mills, sculptor of the equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Square, opposite the White House. When she demonstrated her ability to work clay into recognizable form, Mills took her on as a student and assistant, instructing her in the rudiments of three-dimensional representation. From Mills she would also have gleaned insight into the art of lobbying for government commissions.

Benjamin F. Smith, The Bronze Statue of Andrew Jackson (by Clark Mills) at Washington, DC, lithograph with watercolor, 1853, The Historic New Orleans Collection, New Orleans, LA, USA. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

In the late winter of 1865, Ream visited the president at the White House to do some portrait studies. Soon after that, on April 14, 1865, he was assassinated, and Congress announced it would fund a memorial to the slain president. Ream moved quickly to take advantage of her position as the last artist to depict him in life and submitted a plaster model. She then aggressively lobbied the many government officials who were involved in the selection process, trying to convince them that she was the ideal candidate. In the end, she achieved something remarkable. She created an empathetic Lincoln who established a bond with visitors of all backgrounds.

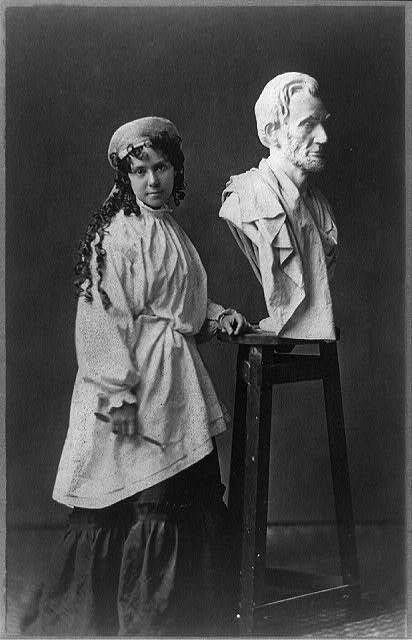

Photo of Vinnie Ream posing with one of her early portrait busts of Lincoln, c. 1866, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

In 1869, Ream departed for Europe to produce a finished marble figure. While in Rome, the American expatriate George Peter Alexander Healy painted her portrait, highlighting her luxurious tresses and independent spirit. Those features had caught the eye of many admirers, from Union General Tecumseh Sherman to Confederate General Albert Pike and a string of congressmen and senators. She had to focus on preparations for her statue though.

George Peter Alexander Healy, Vinnie Ream, ca. 1870, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. Gift of Brigadier General Richard L. Hoxie.

First Ream needed to select the perfect block of marble. She followed in the footsteps of Michelangelo to Carrara, located on the northernmost tip of Tuscany, where marble had been quarried for nearly 2,000 years. (The Metropolitan Museum features film footage of marble quarrying.) Local stonecutters then used her plaster model to reproduce a life-sized marble statue, to which she would add the finishing touches.

Later critics would denounce her for not carving it herself. However, in the 19th century it was common practice for even the most famous male sculptors to turn such specialized work over to experienced artisans. Finally, Ream had to organize the careful packing of the sculpture to be sent across the Atlantic, and hope that it would not be damaged or lost in a shipwreck.

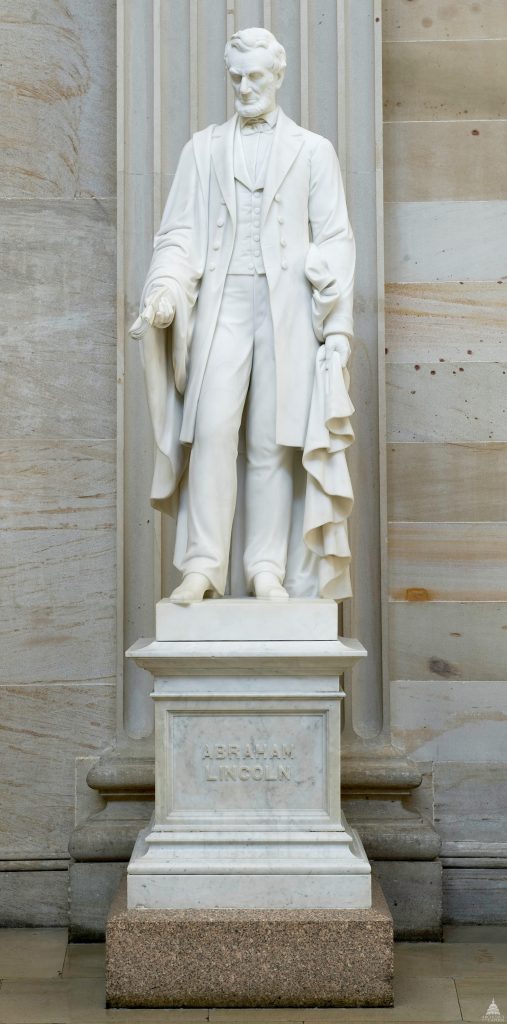

After 18 months, Ream returned to America. On January 25th, 1871, government officials, reporters, socialites, and a few artists gathered – by invitation only – in the US Capitol Rotunda. They braved the winter weather to witness the unveiling of the Lincoln statue.

Vinnie Ream, Abraham Lincoln, 1871, Washington, DC, USA. Architect of the Capitol.

Workmen placed the large wooden shipping crate in the US Capitol Rotunda and then dismantled the crate to reveal a 7-foot-high form, sheathed in cloth. The tension mounted. The audience was intensely curious about the appearance of the controversial artwork. Also the artist was visibly nervous, described by Washington Evening Star editor as “pale and anxious, and rendered more childlike in appearance by her petite form and Dora-like curls”. How could she possibly have imagined she could please these friends and associates of the slain president? As the cloth was slowly raised, like a window shade, his name chiseled on the base appeared, and then his feet, legs, torso, and finally his head. Quickened heartbeats marked the minutes while the guests took their first long look.

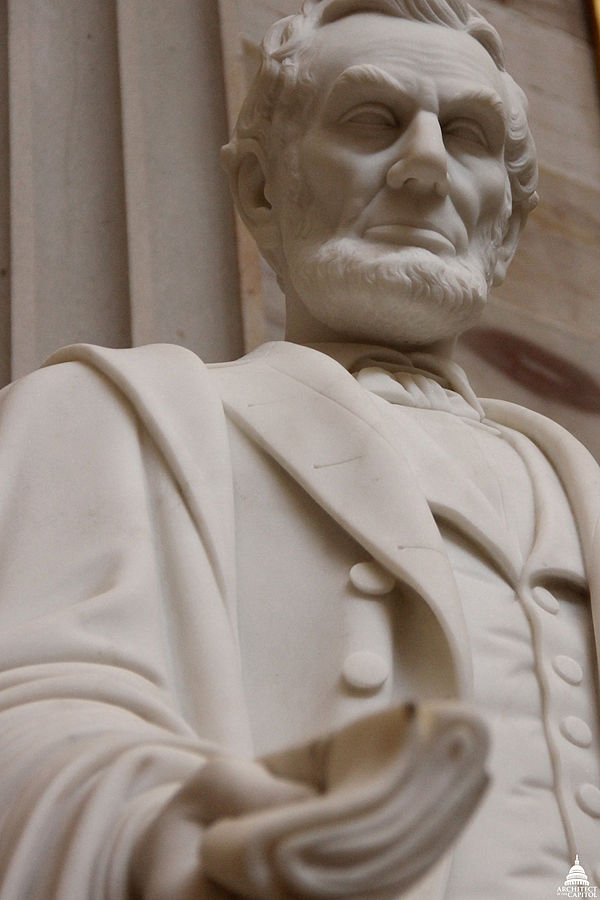

Ream’s Lincoln stands upright, with his right foot positioned just beyond his left. He wears the suit he wore the night of his assassination at Ford’s Theater — which the sculptor borrowed from his widow to depict it accurately. His evening cape, draped over his shoulders and clasped in his left hand, provides needed volume to his tall, thin body, for he had become stooped and gaunt after leading his country through four years of civil war. Adding these physical details, Ream moved away from the earlier Neoclassical style and toward Realism. Soon applause broke out. Not even her highly successful sister sculptor Harriet Hosmer had been so honored.

Vinnie Ream, Abraham Lincoln, 1871, Washington, DC, USA. Photo by Matanya via Wikimedia Commons (CC0).

In 1871, public sculpture was still in its infancy in the US. However, that did not stop journalists from delivering harsh criticism, belittling Ream’s artistic abilities and claiming she only got the commission by “bewitching” the congressmen. The young sculptor must have privately despaired but publicly she kept up a brave front.

Consolation came on January 26th, when a large contingent of Washington’s Black population climbed the stairs of the Capitol to view her Lincoln. They must have admired the sorrowful expression Ream gave him, with features that are softer and more human than in other portraits. “I think that history is particularly correct in writing Lincoln down as the man of sorrow,” she observed.

The one, great, lasting, all-dominating impression that I have always carried of Lincoln has been that of unfathomable sorrow, and it was this that I tried to put in my statue.

With his right hand holding out the Emancipation Proclamation ending slavery, his head is bent forward as if to offer it to an imagined audience of the enslaved.

Maya Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 1982, National Mall, Washington, D.C., USA. Pinterest.

Today more people visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial than any other site on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Its creator, Maya Lin, confessed that she was shocked when competition officials came to her dormitory room at Yale University in May of 1981. They informed the 21-year-old that she had won the design and the $20,000 first prize.

Once the public realized that a young woman had been chosen to create the monument, outcry followed. In many ways Maya Lin suffered some of the same treatment as Vinnie Ream 115 years earlier. The U.S. Congress awarded Ream $10,000 in 1866 (the equivalent of almost $200,000 in 2023) to cover her fee, travel expenses, and materials. Before she could even start to work, Ream—like Lin after her—found herself at the center of a heated controversy about women, politics, and the importance of art to the nation. With talent, sheer tenacity of will, and a lot of help from some extremely powerful friends, Ream managed to realize her dream. It was an old Washington story.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!