The Downfall of the Mighty Lydian King Candaules in Art

Suppose you are not satisfied with any of the historical or fantasy dramas out there lately where all kinds of slander, deception, and politicking...

Erol Degirmenci 2 March 2023

Have you ever been so in love with a scene from a book that it made you think (perhaps out loud): “Well that would make a perfect painting”? If you have ever experienced this, you shared a feeling with numerous prestigious painters. But while we can only speak about books we love, painters can depict what they feel. Therefore they express their admiration through artworks where literature meets painting.

Since antiquity, literature in all its genres has inspired painters to pick up the brush and retell a story with lines and colors. Greek and Roman mythology, the Bible, and other holy books (if we consider them as literature) were the most widespread sources of references for painters. European churches and cathedrals are a living statement of how much biblical stories have influenced painting and art in general (and still do). Most of the time, painters depicted the fatalism and the duality of humankind which transcend any notion of space and time, and therefore are relevant even in modern times.

However mythology and holy books were not the only sources of literary inspiration for paintings. Poems have also been a genre that sparked great works in the history of figurative arts. Dante’s Inferno, from The Divine Comedy, an epic poem that tells the journey of Dante through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, during which he meets his so beloved Beatrice, is a book that inspired many artists. From the original poem’s illustrations to later paintings in different styles and techniques, The Divine Comedy is a noteworthy example of a literary masterpiece that inspired many great artistic works.

As we know, plays are written to be represented on stage but canvas could also be a platform which transfers feelings and emotions from the written form into a visual one. The great William Shakespeare offered painters and many other artists a varied catalogue of so many different human situations that numerous canvases depict famous scenes from his plays. Whether it’s a death scene (Polonius, Ophelia, Desdemona, Romeo and Juliet, you name it!), or an intriguing dialogue (Hamlet with the gravedigger, Hamlet with the ghost of his father…), you can find it painted by someone.

To illustrate these different eras and styles, I present to you five figurative artworks in which literature meets painting.

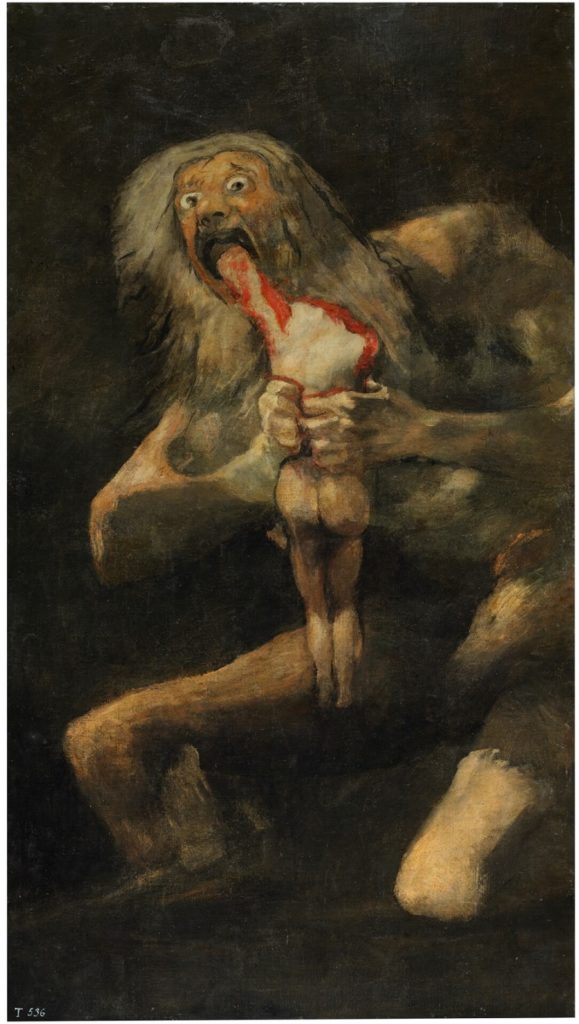

This painting was originally painted on the walls of Goya’s house called Quinta del Sordo (Villa of the Deaf). Alongside the other murals, the so-called black paintings, this masterpiece was not meant to be shown to the public. It is thanks to the Belgian Baron, who came into possession of the Villa after the painter’s death, that we are able to enjoy Goya’s late works.

In this painting, Goya depicts a Greek myth written down by Hesiod in the famous Theogony (although retold by Romans, hence Saturn instead of Cronos). It shows Saturn literally devouring his son in order to avoid the prophecy of the Oracle, according to which he would be dethroned by one of his own sons. Using a stratagem, the god’s wife succeeded in hiding their third son, Jupiter (Zeus), by offering Saturn a stone wrapped in swaddling. Jupiter eventually dethroned his father, just as the prophecy had predicted.

In this painting, we can see that the entire head and a part of the left hand are missing from the son’s naked body. The fierceness and the atrocity of this filicide are omnipresent, not only in the dark colors, but also through Saturn’s scary bulging eyes, and his solid flesh-tearing double grip on his son’s back.

Oedipus, one of the most famous figures from Oedipus Rex, a tragedy by Sophocles, is seen facing the Sphinx, a legendary creature with the head and breasts of a woman, the body of a lioness, and the wings of a bird. The scene is located in a steep rocky landscape. In the background, we see a terrified man running away. He seems to be Oedipus’s companion. Ingres is hinting at the city of Thebes in the barely visible buildings further back at the bottom right.

We can see the monster standing in the shadows of a cave, while Oedipus, naked and holding two spears, is offering his solution to the riddle of the Sphinx. When the monster asked him: “What is it that has a voice and walks on four legs in the morning, on two at noon, and on three in the evening?” Oedipus answered that it was man who, as a child crawls on all fours, as an adult walks on two legs, and in old age uses a stick as a third leg. At the bottom left, a discarded foot and some human bones recall the previous travelers who perished having failed to provide the correct answer.

The outcome of this meeting leads to the suicide of the Sphinx, to the reign of Oedipus on the throne of Thebes, and to his marriage with Jocasta, his widowed mother (Oedipus didn’t know at the time she was his mother, though). In this way, the Oracle’s prediction that he will kill his father and marry his mother is fulfilled (he killed his father on the way to Thebes after a quarrel, thinking he was a stranger). When Jocasta realizes that she had married both her own son and her husband’s murderer, she hangs herself. Discovering his mother’s body, Oedipus then seizes two pins from her dress and blinds himself with them.

The perfection in the depiction of Oedipus’s body and his central position in the painting are contrasting with the shadowed body of the Sphinx, indicating her bad intentions. In such a perilous situation, the expression of serenity in Oedipus’s face demonstrates the typical courage of the great Greek mythological figures.

If the Inferno by Dante Alighieri was only famous for one thing, it would definitely be for its description of the sufferings of the damned in hell.

The scene in this academic painting takes place in the eighth circle of Hell (the penultimate), reserved for falsifiers and counterfeiters. It captures the moment in which Gianni Schicchi, an Italian usurper, barbarically attacks Capocchio, a famous alchemist. We can see the terror on Dante’s face (the man in the red and black outfit at the back), while his guide, the Italian poet Virgil, seems quite indifferent to the fight. The only thing he seems to mind is the petrifying smell, as he’s seen with a pan of his garment under his nose. Tortured souls can be seen in the background of this painting, along with the smiling Devil flying above their heads.

The exaggerated position of the two men’s naked bodies, the perfect depiction of the shape and form of the muscles, the fierceness of the faces, the torn flesh under the attacker’s grip, the swollen veins under the humongous physical effort… all these visual elements testify in favor of this both horrific and extremely beautiful painting. The pictorial realism in the depiction of the two bodies, at which the spectator’s eyes instinctively stare, is of cinematic excellence.

Delacroix was a passionate theatergoer at a young age. He first saw the tragedy of Hamlet in the Odéon-Théâtre in 1827. He was instantly fascinated with the figure of the eponymous character and therefor developed a deep admiration for Shakespeare’s plays.

In this painting, we see Hamlet standing, just a moment before the funeral procession of Ophelia, next to a freshly dug grave where his wife-to-be is supposed to rest after her death by drowning.

He talks to the gravedigger who he has seen unearthing the skull of Yorick, his father’s jester. He used to play with him and to love his jokes. “It makes my stomach turn” (Act V, scene I), Hamlet says as he carries the dead man’s skull. He then starts a long, burlesque meditation about the vanity of life (Alexander’s corpse turning into mud and being used to plug a beer barrel). He also blames the gravedigger for singing in such a solemn occupation.

A moment later he hears a funeral procession approaching. He decides to hide with Horatio. As he sees Laertes, Ophelia’s brother, he finally realizes that his beloved is dead. He then reveals himself and declares his love for her.

Delacroix decided to capture the most intriguing dialogue of this tragedy. He depicts the half-naked chested gravedigger offering the skull to Hamlet as to announce the always approaching death. He directs both his arm and his eyes towards Hamlet’s face, so as to show us on whom we are supposed to focus. Hamlet’s black robe accidentally suits the situation. However, his retreating right arm is a sign of his refusal of death. The gloomy landscape and the clouds hiding the blue of the sky intensify the melancholy of the scene. We are in the presence of death “on and off the screen.”

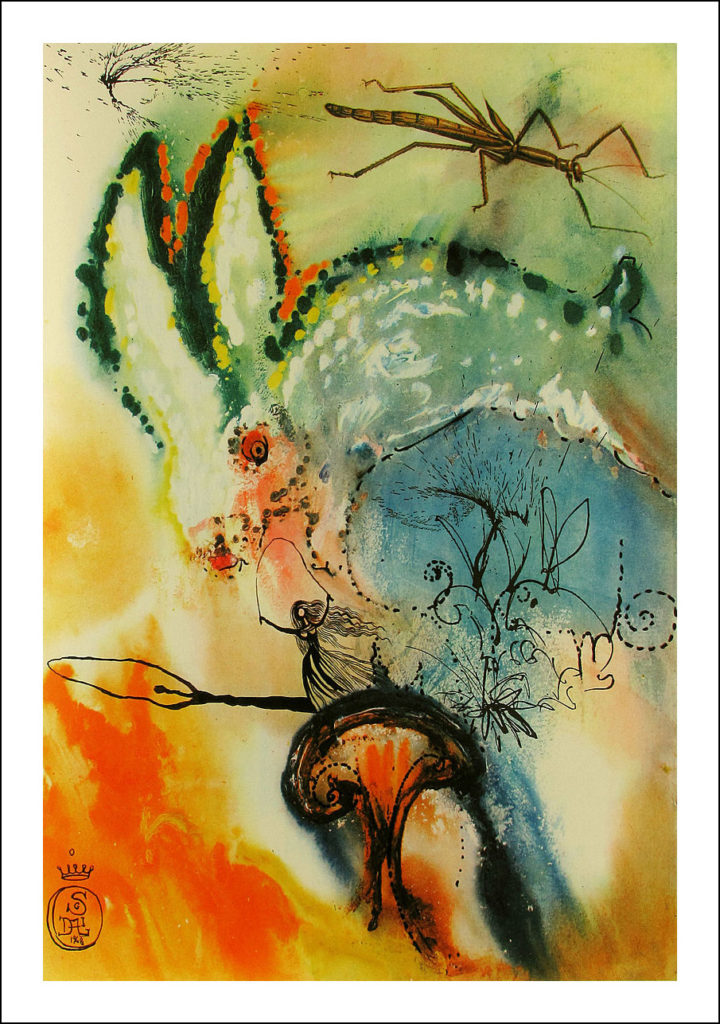

This gouache, along with eleven others and one original signed etching in four colors as the frontispiece, was originally published by Maecenas Press-Random House, New York in 1969, as illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Each gouache was made for a chapter of the book of the same title.

To illustrate the first chapter narrating Alice’s descent into the Rabbit Hole, Salvador Dali explored all the possibilities that dreams could offer. In this gouache, the figure of the rabbit dominates, with its roughly sketched contour “hidden” in the bottom right. Alice is seen playing rope on what it seems to be a mushroom, with her shadow extending to the left of the picture. If we look closely, we can see that Alice’s face is featureless. Dali also inserted a grasshopper, an insect that appears often in his work. At the top left, an unidentified object somewhat resembles a blown pappus of a dandelion. The multitude of “melting” color tones contributes to capturing the dreamy ambiance from Lewis Carroll’s fantasy novel, although the gouaches are appreciated more as interpretations rather than literal illustrations of Carroll’s masterpiece.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!