George Stubbs, Horse Painter

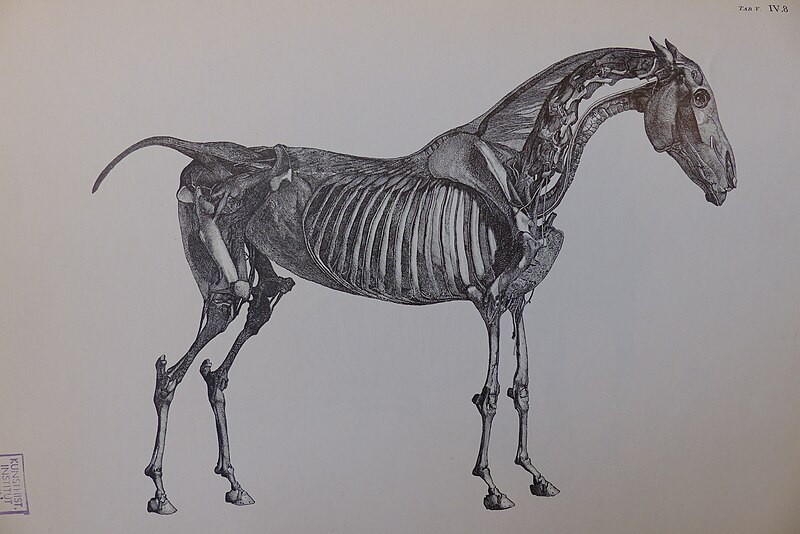

George Stubbs (1724-1806) was a self-taught artist who had an interest in anatomy from an early age. There is a story that a family friend lent him bones to draw as a child. He certainly studied anatomy and dissection in York where he lived for six years in the 1740s. He taught himself to etch and while there was commissioned to illustrate a book on midwifery.

In 1758, Stubbs rented a farmhouse in Lincolnshire and spent 18 months studying dead horses. Gruesomely stringing the carcasses up on a system of pulleys, he injected their veins with wax to give them a lifelike appearance and proceeded to systematically study them in different positions, stripping off each layer of the body.

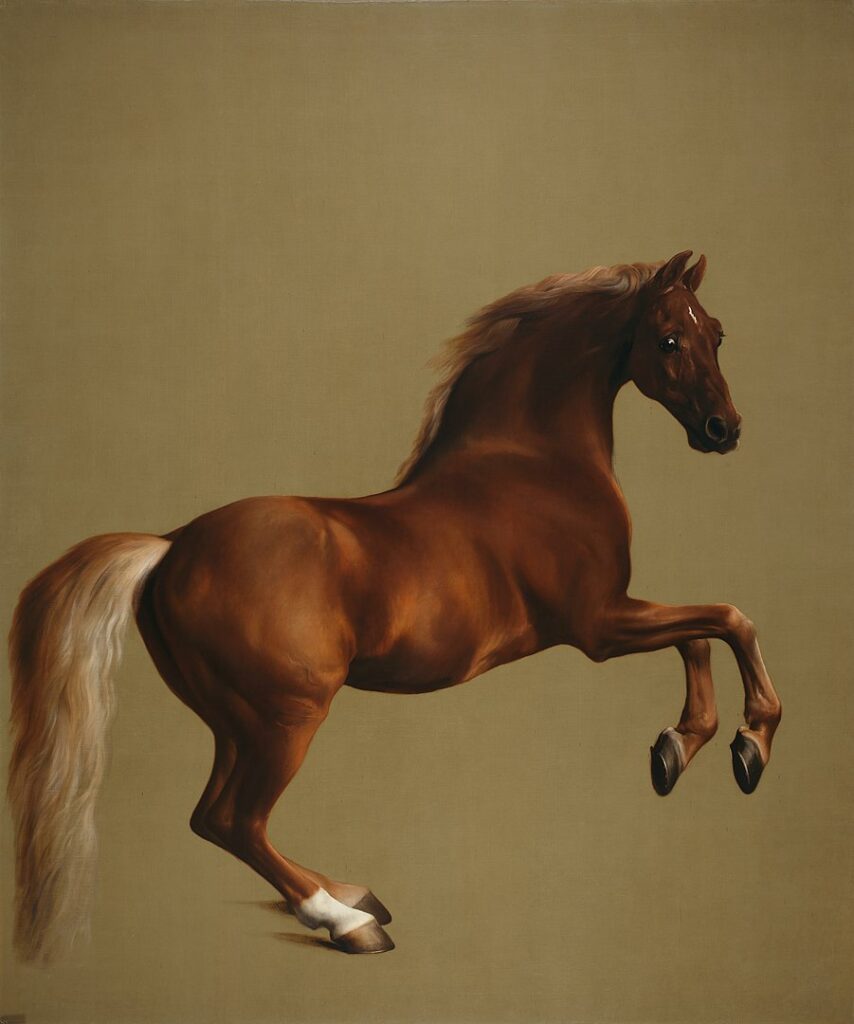

A Horse Called Whistlejacket

Horse racing became very popular among the elite in the 18th century. Successful horses like Hambletonian and Gimcrack had celebrity status and were frequently recorded on canvas. Whistlejacket was certainly not the most famous nor the most successful racehorse that Stubbs painted. Foaled in 1749, he won races in the north of England but lost two out of three times when he ran at Newmarket in 1756 and was sold on by his owner. He subsequently won a race worth 2000 guineas (the equivalent of over £400,000 today) at York in 1759 and was then put out to stud.

Part of Whistlejacket’s appeal has to do with aesthetics. With coppery coloring and lighter mane and tail, he resembled the original, wild Arabian horses he was descended from through his grandfather, the Godolphin Arabian. He was also notoriously difficult to handle, which might explain his short racing career and Stubbs’ choice to show him in a levade, poised on his hind legs, rather than in a more static stance.

Whistlejacket’s Owner

Whistlejacket was owned by the Marquess of Rockingham, twice Prime Minister and one of the wealthiest men in England. Passionate about horses and horse racing, he had a stable of 200, including Whistlejacket, which he bought in 1756 when the horse was seven.

Rockingham lived at Wentworth Woodhouse in Yorkshire, which had the longest façade of any house in England. He owned one of the best collections of classical sculpture in the country, which he had collected on the Grand Tour. He also got the most celebrated artist of the day, Sir Joshua Reynolds, to paint his portrait.

It was perhaps inevitable that Rockingham sought out the up-and-coming animal painter Stubbs, who had already been commissioned by other leading members of the aristocracy. In 1762 he invited the artist to stay at Wentworth for several months and paint his horses, including Whistlejacket. In all, Stubbs would produce twelve paintings for him over a period of four years.

Whistlejacket remained a significant painting for the family. The house was later remodeled with an entire 40ft square room created to showcase Stubbs’ work. It was only sold to the National Gallery in 1997.

Is it finished?

The most striking feature of Whistlejacket is the lack of background. This was unusual even in Stubbs’ work and led contemporaries to think it was unfinished. It was not uncommon for a specialist animal painter to work with another artist who would provide a landscape background. Stubbs himself worked with artists including George Barret in exactly this way.

A story grew that the painting was intended as an equestrian portrait of George III, which would have been finished by portrait and landscape specialists and given by Rockingham as a gift to the King. Whistlejacket’s rearing pose certainly mimics royal portraits by artists like Velazquez. It is possible that Rockingham could have intended such a portrait and changed his mind for political reasons.

However, it is much more likely that Rockingham wanted Stubbs to leave the background plain. Certainly, the shadows under the back hooves suggest this. Stubbs also painted two other, smaller works without backgrounds, including Mares and Foals, which were designed to hang alongside Whistlejacket.

Given that Rockingham was a collector of antique sculpture, it is likely that the concept of the plain background was inspired by classical reliefs. Mares and Foals with its complex composition of overlapping bodies and legs mimics a classical frieze, like those seen on the Parthenon Marbles. Stubbs would have seen similar examples from classical Rome on his one trip to Italy in 1754, as well as in the collection at Wentworth.

A Portrait of a Horse

Stubbs combined his knowledge of anatomy with his powers of observation to create a painting which was lifelike and characterful – a true portrait. Whistlejacket poses with his head slightly turned towards us, just as a human portrait might be. A look of wariness, perhaps even fear, is clearly visible in his eye, picked out by the white highlight.

Although the painting looks crisply outlined and precisely finished from a distance, up close the brushwork is loose, the lines softened, the mane merely sketched in. This broad handling adds to the sense of life and naturalism.

The dramatic stance creates the impression of a moment of captured time and allows Stubbs to show raised veins and active muscles, emphasizing that this is a living, breathing animal. At the same time, he shows the individual markings, like the white sock and forehead flash, which make Whistlejacket recognizable.

The first biography of the artist contains the story that as he was finishing the canvas in the stables, Whistlejacket was led past and reacted violently to the sight of the painting, thinking that it was a rival stallion. It may not be true. Roman writer, Pliny, has a similar anecdote about Greek artist, Zeuxis, who painted grapes so realistically that birds tried to peck at them. However, there is no doubting the realism of Stubbs’ portrayal of Whistlejacket.

All of Stubbs’ equine paintings were carefully observed from life. What sets Whistlejacket apart is its life-size scale and dramatic pose. Stubbs seems to be deliberately challenging the academic hierarchy, which placed animal painting below both portraiture and mythological and historical subjects.

Joshua Reynolds was at this time producing life-size, Grand Manner portraits which recreated classical poses for his contemporary patrons. In Whistlejacket, Stubbs certainly seems to be taking a similar approach to animal painting. Perhaps also the self-taught Stubbs is showing off his ability to work on the same scale and grandeur as the most famous artists of the day.

Whistlejacket is treated like an individual by Stubbs, but he also turns into a Romantic hero. The lack of saddle or bridle, or the presence of humans, gives him a sense of freedom and wildness. The dramatic pose, the flowing mane and tail, and the slightly wild look in his eye create a narrative of drama and tension.

Stubbs produced many images of wild animals, including a series of seventeen paintings showing a horse being attacked by a lion. These were allegedly based on an event the artist witnessed in North Africa while returning from Italy. He certainly made sketches of lions which were kept at the Tower of London. In many of the versions, the horse is an Arabian with similar coloring to Whistlejacket.

These imagined scenes can also be seen as evidence of a growing interest in Orientalism. Arabian horses were exotic animals, beautiful but dangerous. They had been tamed and improved by English thoroughbred breeding, and were usually shown in the polite confines of English landscape and country house parks.

Whistlejacket is a crossover between these fantasy images and the observed realism of Stubbs’ other racehorses. Without background, harness or human figures, the horse is divorced from ‘civilization’. The sad truth is that he was a moderately successful, now-retired, stud stallion.

The scale of Whistlejacket is enough to guarantee attention. The minimalism of Stubbs’ canvas appeals to modern tastes. The lack of background means it exists beyond time and place; it feels relevant rather than historic. However, Stubbs’ real skill was to create both an archetype – our idealized image of a horse – and an individual animal with a personality. Viewers look into Whistlejacket’s eye and feel a connection. That’s the real power of the painting.